Woody Guthrie: Spokesperson for the Lost

Woody Guthrie: Spokesperson for the Lost

Z. Pontz: Guthrie Dreams

The latest drama by playwright and actor Michael Patrick Flanagan Smith opens with a dying man lying supine in bed, ravaged by the effects of Huntington’s disease. But this is no ordinary man. He’s an iconoclast, one of the original artist-activists, a major influence on the 1960s civil rights movement, a man who could reduce counterculture demigods like Bob Dylan and John Lennon to mere idolaters. This man is Woody Guthrie, and in Woody Guthrie Dreams, which ran at the Theater for the New City in Manhattan’s East Village in September, this is how we first find the legendary folksinger (played by Smith): alone, immobile, and impotent, hanging on to the last remnants of a life of extreme vicissitudes. This version of Woody is a mere shadow of the celebrated folk troubadour, and for the rest of the play we watch as this all-but-dormant body slips into a retrospective reverie.

The latest drama by playwright and actor Michael Patrick Flanagan Smith opens with a dying man lying supine in bed, ravaged by the effects of Huntington’s disease. But this is no ordinary man. He’s an iconoclast, one of the original artist-activists, a major influence on the 1960s civil rights movement, a man who could reduce counterculture demigods like Bob Dylan and John Lennon to mere idolaters. This man is Woody Guthrie, and in Woody Guthrie Dreams, which ran at the Theater for the New City in Manhattan’s East Village in September, this is how we first find the legendary folksinger (played by Smith): alone, immobile, and impotent, hanging on to the last remnants of a life of extreme vicissitudes. This version of Woody is a mere shadow of the celebrated folk troubadour, and for the rest of the play we watch as this all-but-dormant body slips into a retrospective reverie.

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in Okemah, Oklahoma in 1912 to Charles and Nora Belle Guthrie. His was initially a life of country quaintness, but at the age of seven his older sister died in a coal oil fire accident, and by the age of eight his father had met financial ruin while his mother began to show signs of the Huntington’s disease that would prematurely kill her. By 1927 he had been left in the care of his eldest brother Roy while his dad worked in Texas and his mother was in the hospital, where she was committed for insanity due to a misdiagnosis. By the age of nineteen Woody was married and heading west to California with millions of Dust Bowl migrants. This period marked the beginning of Guthrie’s peripatetic and independent lifestyle, and effectively shaped his political character as well. He experienced firsthand the poverty and exploitative conditions that migrants were subjected to.

Smith, who is a musician as well as an actor and writer, was originally drawn to Guthrie in 2004 because of his music. But extensive research, which led him to the Woody Guthrie archives in New York and included interviews with close Guthrie confidant and traveling partner Pete Seeger as well as Guthrie’s daughter Nora, revealed to him different complexions of Guthrie’s life. The play, as a result, adopted a theme and tone of flawed character and failed activism that has been largely absent from discussions of Guthrie. “People think of him as this saintly person who wrote ‘This Land is Your Land,’ which we all sung along to in school, but that wasn’t who he actually was,” Smith told me.

Guthrie was a radical leftist and a devout Communist. He stood by Stalin even after the great purges and famines, advocated isolationism while Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini began to carve up Europe, and ridiculed Roosevelt for his New Deal. Guthrie ultimately came around to the cause of the Second World War, serving in the Merchant Marine and even becoming an admirer of Roosevelt’s, but the postwar years saw him grow increasingly alienated from the unions he had supported, as they cast off their Communist roots in the face of the Cold War. As Eisenhower’s stifling fifties closed in around him and the McCarthy era dawned, friends such as Pete Seeger were blacklisted for their Communist activities and affiliations, and Guthrie became paranoid and defensive.

Like many brilliant artists, Guthrie was a mass of contradictions. He touted peace but sung often of war, he took a job as a radio host for Model Tobacco Company despite his contempt for capitalism, and though sympathetic to the plight of mankind he was known to act terribly toward his wives and was often absent as a father. In the end, he fathered eight children and left three wives, the first of which he abandoned while pregnant.

Yet as Will Kaufman wrote in his book Woody Guthrie: American Radical, “All the negatives and the contradictions simply make him less of a saint, and more of a committed, flawed human being immersed in political complexity and a harrowing personal struggle.” Woody Guthrie Dreams confronts those failures and paradoxes of Guthrie’s life, depicting a man both tormented by and unwilling to settle for the status quo. It also sheds some insight into the relationships he had with the other songwriters and musicians who supported him for much of his career, like Cisco Houston and Lead Belly, as well as the aforementioned Seeger and Alan Lomax, all of whom held Guthrie in high regard. And then there are the many demons he constantly battles, and with which he never fully comes to terms: his philandering, his struggle with the limitations of art and humanity, and finally his disease.

But the most revealing aspects of the play are connected to Guthrie’s sense of justice. In one scene he reads reports of a plane crash that killed twenty-eight migrant workers in Los Gatos Canyon, California who were in the process of being deported to Mexico. He focused his anger at the story into his famous song “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos).” This is quintessential Guthrie: a man channeling his rage through an acoustic guitar.

Today, with the recession-sparked social upheaval of the Occupy protests, America could use a Woody Guthrie or two. He and his predecessors Will Rogers and Joe Hill, and his successors Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, placed themselves at the center of the disenchanted, helping channel their discontent through music. Guthrie et al were artists of integrity who, if not always holding fast to their ideals, at least strove to apply in practice the social values they advocated, in a way that many contemporary musical artists (like Kanye West, a recent visitor at Zuccotti Park) have not. Guthrie himself sacrificed luxury and even comfort throughout his life. In 1940 the Model Tobacco Company was paying him $180 a week (a substantial sum at the time) to host a radio program, but he abruptly quit when executives began to interfere with his artistic independence. That sort of integrity is important to remember at a time when much artist activism can seem like little more than a publicity stunt. (Take Jay-Z’s recent attempt to sell stylized Occupy Wall Street t-shirts, to enrich not OWS but rather his clothing company, Rocawear.)

As people have begun to return to the streets in protest, Guthrie’s legacy can be seen in the nameless guitar-wielding individuals populating various OWS camps around the country. Hopefully they take heed of Guthrie’s example that simple and modest actions can effectively prove a point—if not on a grand scale, then on a small one that has the power to multiply. “You could say he was a spokesperson for losers who lost lost lost,” Smith noted to me. “And that is what is so inspiring about Guthrie…Because he aimed for fixing the biggest problems, he used the tools he had on hand and he never ever accepted defeat. It is a brilliant act of defiance and it really requires a near measureless heart.”

Zach Pontz is a writer based in New York.

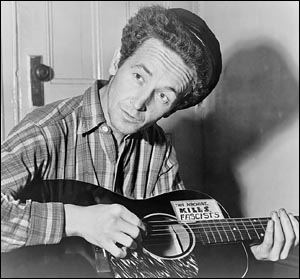

Image: Woody Guthrie in 1943 (Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)