Will Federal Workers Rediscover Their Militancy?

Will Federal Workers Rediscover Their Militancy?

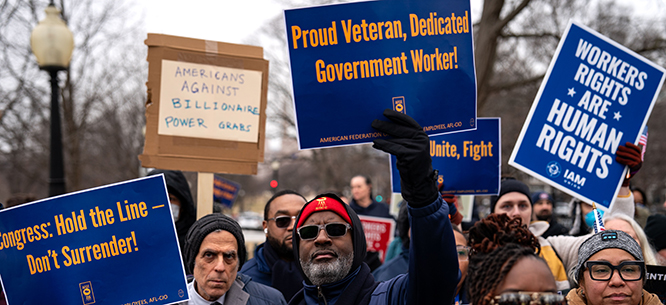

Trump has destroyed a federal system of labor relations that helped contain conflict for decades. The move could have unintended consequences.

On March 27, President Donald Trump summarily overturned decades of federal labor relations policy and stripped more than 700,000 government workers of their union rights with a stroke of his sharpie. His executive order Exclusions from Federal Labor-Management Relations Programs, which effectively voided union contracts at dozens of departments and agencies, constitutes by far the largest and most aggressive single act of union-busting in U.S. history.

The stated rationale for Trump’s order—that the targeted workers are in agencies that affect national security and they therefore are ineligible for union representation—is flimsily transparent. Even the White House can’t sustain the lie. The administration’s own fact sheet points to the president’s real motivation. His order targets agencies whose unions “have declared war on President Trump’s agenda.” How have these unions “declared war”? Apparently, simply by attempting to enforce labor contracts and represent members in grievance proceedings. As the fact sheet notes, Veterans Affairs (VA) workers are losing their rights because their unions had the temerity to file “70 national and local grievances over President Trump’s policies since the inauguration.”

It is obvious that Trump is exacting revenge on unions that are challenging the draconian cuts and closures inflicted by Elon Musk’s renegade Department of Government Efficiency. Tellingly, unions believed to be sympathetic to the Trump agenda, such as those that represent federal law enforcement workers (whose work is more closely related to national security than that of, say, VA nurses or employees of the General Services Administration), have been exempted from his sweeping action.

The Radicalism of Trump’s Union-Busting

With his radical and blatantly political order, Trump, like a deranged Samson, is straining to pull down the solid pillars that have undergirded a remarkably stable system of federal labor relations for decades. If he succeeds, his action threatens many millions more than the federal employees directly affected by his executive order. As the nation’s largest employer, what the government does to labor inevitably ripples through the entire economy.

The only event in U.S. history comparable to Trump’s action is Ronald Reagan’s firing of some 11,500 striking air traffic controllers in 1981. Reagan’s crushing of the controllers’ union, PATCO, brought to a screeching halt the rapid expansion of public-sector unionization in the 1970s and catalyzed a wave of strikebreaking by private employers that set back the entire labor movement. In some ways, labor still struggles with the fallout of that fateful conflict. If Trump’s current action stands, its destructive force promises to be many orders of magnitude larger than the PATCO affair.

To grasp the enormous implications of Trump’s order, consider the elements of the time-tested structure that he is busy pulling down. The first pillar of the system was put in place in 1883 with the Pendleton Act, which created the federal civil service to professionalize those who worked in government and to end the spoils system that allowed the party in power to oust the personnel of federal agencies and install its supporters no matter their qualifications. Under the U.S. Civil Service Commission, federal workers freed themselves not only from fealty to corrupt political bosses but also from the status of at-will employees who can be fired for any lawful reason, or no reason—the condition under which most American workers, who lack union representation, operate to this day. As the civil service emerged, one of its central ideas was that its competent workers could not be fired without cause.

The second pillar of the system was put in place by the executive actions of a bipartisan line of presidents—Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Richard Nixon—each of whom played a role in expanding federal workers’ collective bargaining rights with the government. The first step was taken by Roosevelt. In addition to signing the Wagner Act, which finally guaranteed most private-sector workers the right to unionize in 1935, he allowed a few federal agencies such as the Tennessee Valley Authority to bargain collectively with unions representing their tradesmen. Roosevelt’s experiment was seized upon and expanded by Kennedy. As Cold War imperatives made it unseemly for a government that claimed to lead the free world to deny its own employees any voice over the terms and conditions of their labor, Kennedy institutionalized collective bargaining for most federal workers by executive order in 1962. Seven years later, Nixon signed an executive order that further strengthened federal union rights and simplified the process through which workers chose union representatives.

In 1978, these two pillars were strengthened by a connecting arch, the Civil Service Reform Act (CSRA). Passed by bipartisan majorities and signed into law by Jimmy Carter, the CSRA created a solid structure connecting civil service and collective bargaining that has endured for almost a half-century. The CSRA defined and updated the rules of the federal civil service, while placing on solid legislative footing the collective bargaining rights that were first outlined in Kennedy and Nixon’s executive orders. The act also created two new enforcement agencies: the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA), whose purpose was to adjudicate disputes between the government and the unions representing its employees, and the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), which was created to guarantee workers due process if they were wrongly fired, demoted, or disciplined.

The system of federal labor relations that took final form in 1978 was founded on three basic principles: First, federal workers, as civil servants, were not to be treated as at-will employees who could be fired without cause. They had the protections of a civil service regime in which they were guaranteed due process. Second, excepting employees of the FBI, the CIA, and select others involved in “primarily performing intelligence, investigative, or security functions” (in the language of Kennedy’s order), federal workers had a right to organize and bargain collectively. Third, federal workers’ union rights were limited: they were not authorized to bargain with agencies over their pay and benefits, because these matters were set by Congress, nor could they engage in strikes or other job actions like slowdown or sickouts.

The system proved remarkably durable, surviving multiple crises and controversies. It was first put to the test in 1981, when frustrated air traffic controllers who believed that Reagan had promised them big pay increases in return for their endorsement of his presidential campaign defied the strike ban and walked off the job. When the strikers ignored Reagan’s ultimatum and refused to return to work, they were fired and permanently replaced. Many activists called for other federal workers to walk out in sympathy with their PATCO colleagues. But the unions representing other federal workers had no interest in challenging a system they thought was basically fair in order to support a union that had blatantly defied its rules. Labor’s failure to challenge the PATCO firings made it possible for Reagan to break that union, and to enjoy significant public support in doing so.

The system was again tested in the aftermath of 9/11. When the Department of Homeland Security was created under George W. Bush, it merged several existing agencies into a mammoth bureaucracy of 177,000, including 56,000 screeners working for the Transportation Security Administration. The Bush administration declared that all DHS workers, including those at TSA, were excluded from the union rights guaranteed by the CSRA. Fighting terror, they claimed, demanded a “flexible workforce” that was “not compatible with the duty to bargain with trade unions.” John Sweeney, then president of the AFL-CIO, alleged that the Bush administration was “using war as a weapon to deny rights to the very workers it relies on to win the war.” But labor’s opposition to Bush’s decision did not rise above the level of scorching rhetoric. Instead, leaders waited patiently for a new administration, and after his election, Barack Obama removed the ban on unions at TSA. By 2012, TSA screeners had won their first union contract.

The importance of the TSA workers’ victory became clear during the federal government shutdown of 2018–19, when a host of federal workers, including TSA screeners, worked without pay for thirty-five days. As the shutdown dragged on, many observers worried that screeners might stage a coordinated sickout in protest of their lack of pay. While their absentee rates did rise, no concerted job action crystallized during the shutdown in part because the TSA screeners’ union, the American Federation of Government Employees, actively discouraged any talk of a job action that might trigger union decertification.

Ironically, it was a small number of strategically placed air traffic controllers who finally brought the shutdown to an end when they called in sick, causing a ground stop at LaGuardia Airport on the morning of January 25, 2019, which led the Trump administration to fold by that afternoon. The union that represented those workers, the National Air Traffic Controllers Association—PATCO’s successor—utterly disavowed any responsibility for their action. I had found out a week before that episode just how afraid NATCA was of any suggestion that its members might stage a job action. When I mused in the American Prospect that a controllers’ sickout would end the shutdown in short order, one NATCA official furiously criticized me for even having uttered that thought in public.

In each of these instances, the seeming stability of the federal system of labor relations and federal unions’ deep investment in preserving that system functioned to contain conflicts that otherwise might have spiraled. Now that system is all but destroyed. After mere months in office, Trump has systematically subverted a robust structure that took decades to build. He fired FLRA chair Susan Tsui Grundmann and MSPB chair Cathy Harris, ensuring that henceforth those adjudicating agencies will do his bidding. He effectively shuttered agencies like USAID and turned whole categories of workers—such as those engaged in DEI work—into at-will employees to be fired without due process. And now he has apparently delivered his coup de grâce, demolishing the union rights federal workers have enjoyed for decades.

What Next?

While the Trump order threatens to produce a veritable nuclear winter in U.S. labor relations, its very radicalism makes its long-term impact more unpredictable. The past is full of cautionary tales reminding us that the more an ambitious actor tries to bend history to their will, the more likely the unintended consequences of their actions will undo their grand plans.

One unintended consequence of Trump’s move is that it could very well rouse the union movement and its allies to a more confrontational opposition to his agenda than anyone could have foreseen. Up to this point, federal unions have confined their resistance to filing lawsuits and contract grievances, circulating petitions, holding rallies, and lobbying legislators. Unions have not contemplated job actions to date in large part because they are forbidden by law; engaging in them could lead workers to lose their jobs and cost unions their certifications as bargaining agents, as happened in the PATCO case. But will calculations change in a world where workers no longer feel protected by civil service regulations and their unions have already been decertified for all intents and purposes?

As the sociologist C. Wright Mills observed long ago, where they are firmly established unions tend to act as “managers of discontent.” They seek to direct their members’ grievances into channels that might produce significant—if usually incremental—gains, and to restrain their members from actions that might threaten the union’s survival or damage its credibility as a reliable negotiating partner in the eyes of management. Yet what happens to workers’ discontent when unions are no longer able to play that role? And what happens to union behavior when the system in which they have invested and from which they derived their own stability is shattered?

Up to this point, most federal workers have operated as though the old assumptions still hold true, believing that the terms and conditions under which they work cannot be revoked by one man’s politically motivated order. Most federal unions believed that a presidential fiat could not override the protections they had under the CSRA as long as their organizations abided by its rules.

As the old order crumbles, however, faith in the courts’ ability or willingness to stand up to Trump’s aggression is waning. On the day after he announced his union-busting executive order, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled 2–1 that Trump had the authority to fire Cathy Harris of the MSPB and Gwynne Wilcox of the National Labor Relations Board in the middle of their Senate-confirmed terms. In his concurring opinion, Judge Justin Walker, a Trump appointee, argued that the Constitution’s framers vested in the president “full responsibility for the executive power.” It seems likely that a majority of justices on the current Supreme Court will arrive at the same conclusion when Trump’s wholesale restructuring of federal labor relations reaches their docket—unless something changes the present dynamic.

Can unions bring about that change? The day after Trump’s order was announced, the AFL-CIO acknowledged the existential threat it posed. “No union contract is safe after last night,” it said. Yet whether unions feel incentivized to resist Trump’s attack with more than rhetoric, lobbying, and redoubled lawsuits is an open question. Union leaders realize that the sudden conversion of federal workers to what is effectively at-will employment status and the simultaneous termination of their bargaining rights merely puts them in the same position as the vast majority of private-sector workers, who lack both union representation and employment security. Could the public be stirred to support government workers in a confrontation with the Trump administration? Uncertain of the answer, union leaders are likely to continue to take a cautious approach to this crisis—at least in the near term. Yet even if union leaders do not seek it, an escalating confrontation is more likely now than it has been in generations.

It is worth remembering that federal labor relations were not always as pacific as they have been in recent decades. One reason that Kennedy signed his 1962 executive order was to head off growing unrest among federal employees. Although it has long been illegal for federal workers to engage in strikes, such actions were not uncommon during the years when the system of federal labor relations was under construction. (Between 1956 and 1961, there were ninety-two work stoppages at Cape Canaveral, where America’s space program was based.) Nor did the Kennedy and Nixon executive orders eliminate such activity. Between 1962 and 1981 federal workers engaged in thirty-nine illegal work stoppages.

Unrest among federal workers peaked in March 1970—after the executive orders were promulgated. In that month, hundreds of thousands of postal workers defied the federal ban on striking and staged an eight-day wildcat walkout, frustrated by their inability to negotiate over pay under the government’s limited form of collective bargaining. When Nixon called out the National Guard to deliver the mail, postal workers held firm and only returned to work after they were promised a wage increase. Just as they returned to work, several thousand air traffic controllers staged a seventeen-day sickout to protest the Federal Aviation Administration’s refusal to negotiate with their union. Both job actions produced results. The walkout made it possible for postal workers to win the creation of the U.S. Postal Service, a semi-autonomous federal agency that was allowed to bargain with them over their pay. For their part, air traffic controllers were able to speed up the official recognition of PATCO as their exclusive bargaining agent. It was only after PATCO’s ill-fated 1981 strike that job actions by federal workers became exceedingly rare.

Trump’s radical executive order could reawaken this long-dormant tradition of collective action among otherwise seemingly docile federal workers. Such actions, should they arise, will likely not take the form of a strike. There is a long history of slowdowns, sickouts, and work-to-rule actions by federal workers. Such actions are often difficult for the government to detect, let alone defuse. And they do not require official union sanction. Indeed, like the postal workers’ 1970 wildcat strike, these activities tend to be more effective and harder to defeat when they are unofficial.

Prior to Trump’s executive order, federal unions were experiencing a surge in membership. Moribund locals were springing to life and new ones were in the process of formation. A new group, the Federal Unionists Network, emerged to coordinate activity at the grassroots level across many agencies and unions. This energy will undoubtedly seek an outlet. If there are no longer structures in place to direct that energy into orderly channels, then it could take surprising forms in the months ahead.

There is at least one piece of evidence that the Trump administration is worried about the prospect of a debilitating job action. The one group of federal employees whose work is clearly intertwined with national security—but who also happen to boast a history of job actions—was conspicuously exempted from the union-stripping provisions of Trump’s executive order: air traffic controllers. Apparently, the administration is reluctant to antagonize workers who have the power to snarl air traffic if a small, strategically placed group of them simply call in sick.

Will federal workers rediscover the militancy that was once not uncommon in their ranks and resist Trump’s union-busting with collective action? Will the broader union movement and its allies stand with them, putting their own organizations on the line to defend workers’ basic rights? On the answers to those questions will turn not only the fate of the union movement for decades to come, but of a multiracial American democracy in which the right to collective bargaining has served as an essential pillar for almost a century.

Joseph A. McCartin is the director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, author of Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers and the Strike that Changed America, and president of the Labor and Working-Class History Association.