Trump’s Deportation Model

Trump’s Deportation Model

Trump has invoked a 1950s mass deportation campaign as a blueprint for his nativist agenda. Its history shows that abuse and dehumanization are intrinsic to immigrant detention.

In 2016, Donald Trump’s signature campaign promise was to build a wall between the United States and Mexico. During the current election cycle, Trump has escalated his xenophobic rhetoric and pledged to deport tens of millions of migrants already in the United States if elected to a second term. At an event in Iowa in 2023, he cited a historical precedent for his plan: “Following the Eisenhower model, we will carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

The history of the “Eisenhower model” should give pause to anyone who values the rule of law or human rights. In the early 1950s, U.S. officials became alarmed by a sharp rise in unauthorized border crossings from Mexico. They accused migrants of committing crimes, taking jobs away from citizens, engaging in drug trafficking, and spreading disease. The Border Patrol claimed that this problem could be solved if the government allowed the military and National Guard to help the agency seal the southern border. This suggested fix, however, overlooked an 1878 law known as Posse Comitatus, which prohibits the government from using the military to enforce domestic policies unless such use is approved by Congress. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s former West Point classmate Lieutenant General Joseph M. Swing insisted that the administration disregard the law, but Eisenhower refused.

Trump has shown no such reluctance. In an interview with Time earlier this year, he claimed that he would carry out his plan with the help of the National Guard, along with other branches of the military if “things were getting out of control.”

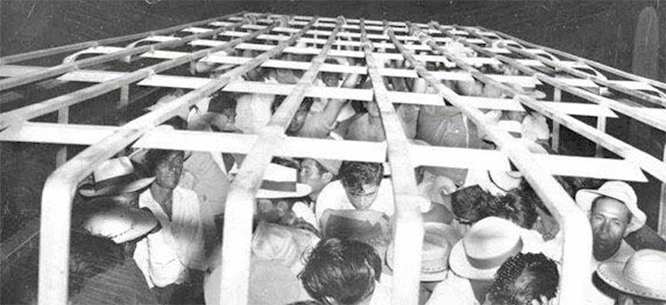

While Eisenhower rejected the use of the army on U.S. soil, he appointed Swing as commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1954. Almost immediately, Swing launched Operation Wetback, a harsh paramilitary campaign to expel Mexicans whose name invoked a derogatory slur for migrants who cross the Rio Grande. The Immigration Service marshalled approximately 750 immigration officers; seven airplanes; and 300 jeeps, cars, and buses to round up migrants. Within three months, historian Mae Ngai notes, the service had apprehended approximately 170,000 people. Given the sheer number of those captured, the government lacked the resources to deport all of them immediately. Instead, it erected temporary detention facilities to hold them while they awaited expulsion.

During his presidential administration, Trump took a similar action by building sprawling camps to detain apprehended individuals before deportation—a measure he plans to expand if reelected. One such facility, which opened in Tornillo, Texas in 2018, housed thousands of minors in tents. While many noted the inhumane conditions at these sites as well as the cruelty of the family separation policy, mistreatment in detention facilities was not unique to the Trump administration. As I show in my new book, In the Shadow of Liberty, abuse and dehumanization have occurred no matter when, how, or why immigrant detention was used—they are intrinsic to the system. In fact, immigrant detention facilities were originally conceived as spaces where the Constitution did not apply.

Just like Trump, politicians and the media in the 1950s spoke of migrants as a faceless, dangerous mass with no humanity. Few records were left of their experiences. But some people have been able to tell their stories. The late former congressman Esteban Torres, a child of Mexican immigrants, recalled that when he was only three years old, his father did not return home one day because he had been deported. “My brother and I were left without a father,” he recounted. “We never saw him again.” Deportation tears families and communities apart; it is traumatic both for those who experience it and for those around them.

Deportation campaigns also infringe on the rights of citizens. During the 1954 operation, the Border Patrol increased surveillance and racial profiling of those who “looked Mexican.” Claiming that many migrants tried to avoid deportation by posing as U.S. citizens, officials insisted that immigration officers had to question anyone who appeared to be from south of the border.

While Operation Wetback did reduce unauthorized border crossings, it did not do so strictly through deportations—as Trump seems to assume. Alongside mass deportations, the government expanded the Bracero Program, a set of agreements between the United States and Mexico that allowed Mexican men to work in the United States legally as contract laborers. As a result, men who had crossed the border before 1954 without papers because they had been denied a slot in the Bracero Program began to come as legal guest workers, thus reducing unauthorized migration.

Other massive deportation campaigns in American history have had similarly pernicious effects. Between 1919 and 1920, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer set out to purge the country of political radicals, often immigrants from Southern or Eastern Europe. During the Palmer Raids, federal, state, and local agents arrested thousands of people whom they believed to harbor revolutionary intentions (First Amendment be damned), detained them at Ellis Island, and eventually deported over 500 of them. Among them was well-known anarchist Emma Goldman, who described the awful conditions during her detention: the “quarters were congested, the food was abominable, and [we] were treated like felons.” These detentions and deportations also ripped families apart: those classified as radicals were sent away, while their parents, spouses, and children remained behind.

In the 1930s, the government launched an even more massive deportation campaign. Amid the hardships of the Great Depression, Mexican migrants and Mexican Americans were blamed, paradoxically, for both taking jobs away from U.S. citizens and relying on public assistance. In response, immigration authorities sought to expel ethnic Mexicans, not only targeting unauthorized migrants but also pressuring legal residents and even U.S. citizens to leave under the guise of “voluntary” departure. Estimates of the number of Mexicans repatriated during this period range from 350,000 to 2 million, with about 60 percent believed to have been U.S. citizens—most of them children.

Though Mexicans and Mexican Americans were blamed for the nation’s problems, their expulsion did nothing to improve the economy. Ironically, just a few years later, during the Second World War, the U.S. government decided that it needed more Mexican laborers in the country to fill the jobs left by American men serving in the military.

Our history speaks loudly to the legal and human toll of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. Scapegoating migrants—much less deporting them—does not solve our social or economic crises. Indeed, deportation has proved time and time again to hurt not only migrants themselves but also their families and communities who stay behind. Anti-immigrant politics have diluted the rights granted by the Constitution and as such threatened all American citizens. We should reject the Eisenhower model—or any other draconian approaches to immigration.

Ana Raquel Minian is an associate professor of history at Stanford University and the author of In the Shadow of Liberty: The Invisible History of Immigrant Detention in the United States.