Trump’s Antisocial State

Trump’s Antisocial State

The administration is attempting to incapacitate the redistributive and social protective arms of the state, while exploiting its vast bureaucratic powers to silence, threaten, and deport.

Just a few months in, any doubts about the tenor of Trump’s second presidency have been dispelled. The Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise by Project 2025 has produced a much more focused Trump than we saw the first time around. It has found a way to convert the president’s flare ups into a constant source of energy and to arrange his thought bubbles into a sequential narrative. Project 2025, as the report has come to be known, contains a plan for reconstructing the American state from the ground up. To get there, however, it first has to overcome obstacles created by the existing state and its workforce of civil servants. One refrain beats consistently throughout: abolish the administrative state. The report whispers in the president’s ear at every turn, explaining how he can use executive power to “fire supposedly ‘un-fireable’ federal bureaucrats; shutter wasteful and corrupt bureaus and offices; muzzle woke propaganda at every level of government; restore the American people’s constitutional authority over the Administrative State; and save untold taxpayer dollars in the process.”

Project 2025 indulges every fantasy of Trump’s cabinet members, a coterie of private fund investors and business founders with preferential ties to the fossil fuel industry, real estate, and Silicon Valley. The manual shows how the president could open up federal lands to fossil fuel prospectors and actively obstruct any progress on climate change mitigation. It shows how the Federal Reserve could abandon its function as lender of last resort and allow for a return to free banking, with gold or some other commodity equivalent (perhaps cryptocurrency) acting as backstops to privately issued money. And it shows how the Department of Housing and Urban Development could sell off the country’s remaining public housing stock and withhold support from low-income borrowers. Meanwhile, the president is urged to dissolve the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (the independent government agency charged with preventing bank runs) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (the agency that recently extended anti-fraud regulation to the digital finance sector). Project 2025 represents the apotheosis of the antisocial state: a state form that has withdrawn from the task of social insurance and placed its entire administrative apparatus in the hands of a small group of uber-wealthy business partners.

Mandate for Leadership is the ninth in a series of presidential user manuals issued by the Heritage Foundation since 1981. Their guiding themes are monotonous: attack government bloat, slash regulations, and defund the left. At over 900 pages, Project 2025 rivals the doorstopper handed to Reagan in 1981. But what really distinguishes this iteration from previous ones is its assumption of vigorous judicial back-up. Trump appointed three new Federalist Society–approved judges to the Supreme Court during his first term. He is now working with a 6-3 conservative majority that has granted him presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for acts extending to the “outer perimeter” of his office. The pages of Project 2025 are littered with abstruse reflections on constitutional law that are likely illegible to the general public. But they would make sense to anyone familiar with the Federalist Society’s judicial critique of the administrative state and the closely allied theory of unitary executive power.

Dating back to the early twentieth century in its American usage, the “administrative state” is a term of art first used by legal realists to describe the kind of government bureaucracy demanded by a modern, industrial society. Progressives saw the New Deal as a high point in modern administrative law. For legal conservatives and libertarians, the term serves as a shorthand for all that is wrong with the contemporary state.

In recent years, the judicial assault on the administrative state has shifted into high gear. The libertarian legal scholar and Columbia University professor Philip Hamburger has played a critical role in this escalation. In Is Administrative Law Unlawful?, his 2014 indictment of administrative tyranny, Hamburger compares the power of modern-day state regulators to the royal prerogative in seventeenth-century England. During Trump’s first year in office, Hamburger founded the New Civil Liberties Alliance, a public interest law firm that purports to “protect constitutional freedoms from violations by the Administrative State.” The NCLA brings cases against government agencies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), challenging settled jurisprudence on the congressional delegation of rule-making power to administrative agencies (the so-called non-delegation doctrine) and on the proper chain of command between the courts and administration (the question of judicial deference).

With a university professor at its helm, the NCLA cultivates an air of lofty nonpartisanship. Yet a look at its case record suggests it is playing an orchestrated game of tag team with the very partisan Cause of Action Institute, a law firm with close links to the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity. In 2024, the firms litigated one case each—Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce—which jointly led to the historic defeat of Chevron deference, a doctrine compelling courts to defer to administrative agencies’ reading of federal statutes. As a result, ultimate authority to resolve conflicts of interpretation—in the matter of climate change or financial fraud, for instance—now redounds to the federal courts. Any disgruntled oil prospector or hedge fund manager can challenge agency jurisdiction over their business dealings and turn to a receptive Supreme Court as final arbiter of the dispute.

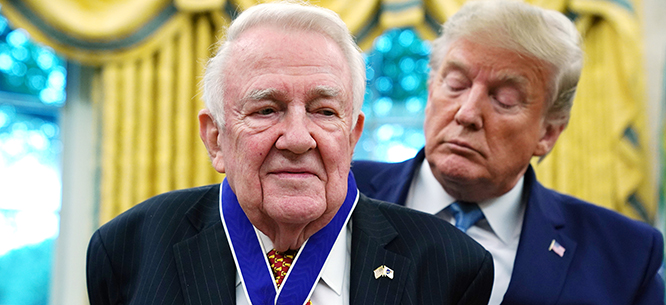

The NCLA is a who’s who of the reactionary legal establishment. Its president and chief legal officer Mark Chenoweth formerly served as in-house counsel for Koch Industries. Its board members include Gary Lawson, a founding member of the Federalist Society and early libertarian critic of the administrative state, and Eugene Volokh, another prominent legal libertarian and Federalist Society stalwart, among others. Collectively, they hope to complete the unfinished business of the Reagan revolution. They hold a special reverence for the legacy of Edwin Meese III, who served as Reagan’s chief advisor in his first term, then as attorney general during his second. (Lawson recently co-authored a hagiography tracing a direct line of descent from Meese to the Trump-appointed justices on the Supreme Court today.)

Meese was both the key in-house enabler of Reagan’s attack on government regulation and an early patron of the Federalist Society. As head of the Department of Justice, he joined forces with other important Reagan officials to obstruct the EPA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and ward off litigation from liberal public interest lawyers. While Reagan appointees waged procedural war on the portfolios under their control, Meese exploited his position as attorney general to expound a radical constitutional critique of administrative power. In a speech delivered to the Federal Bar Association in 1985, Meese complained that administrative agencies had usurped the powers of the legislative and executive branches by claiming the right to freely interpret and enforce federal statutes. He impugned this administrative mission creep as a violation of the Constitution’s separation of powers. Federal agencies, he intoned, “are not ‘quasi’ this, or ‘independent’ that.” According to the strict separation of powers, federal agencies could only be “agents of the executive,” and executive power belonged to the president alone. Under Meese’s direction, the Department of Justice became a haven for exponents of the “unitary executive”—a theory that inflates the so-called vesting clause of Article II of the Constitution to ascribe supreme, king-like powers to the president.

Despite Meese’s ambitions to remake constitutional law, it was on the judicial front that the Reagan revolution ultimately fell short. Reagan cabinet insiders used all the procedural tricks they could to incapacitate maligned federal agencies such as the EPA, but the right-wing attack on the administrative state hit a wall in the courts. As one conservative legal theorist complained, the courts had become a “managing partner in the modern administrative state.”

Almost half a century later, the Federalist Society now virtually owns the Supreme Court. Its conservative majority is well-versed in the constitutional critique of the administrative state and has rubber stamped almost every case teed up by right-wing public interest lawyers. In three recent cases—Lucia v. SEC, SEC v. Jarkesy, and Loper Bright—the court has dramatically curtailed the independent power of agencies to issue, adjudicate, and enforce consumer protections of any kind. The decisions expose all federal regulators to a minefield of future litigation.

In the meantime, right-wing legal theorists have refined the premises of unitary executive theory and broadened its reach to require legislative as well as administrative deference to the president. Most recently, scholars at the Center for Renewing America (founded by Project 2025 co-author Russell Vought in 2021) have conjured the idea that Article II of the Constitution grants the president the right to override or impound funds appropriated by Congress—that is, to defund agencies or programs at will. Trump has refused to spend congressionally approved funds in the past. Elon Musk is counting on him to do the same thing again, this time on a much grander scale, with the help of his newly invented powers of impoundment. For Trump to do so legally would require an overhaul of the Impoundment Control Act of 1974; conservative legal scholars believe they have the constitutional arguments to achieve this. Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett have all issued opinions endorsing some version of unitary executive theory. It remains to be seen how far they will go in validating Trump’s executive fantasies.

The only real surprise is the ubiquity of Musk. This time around, Trump has assumed a trinitarian form: the erratic father has sent his anointed son Musk to micromanage his work on earth, while X pumps the Trumpian spirit into the flesh of his followers. The result, unfortunately, is a much more potent Trumpism.

For all its nihilism, Project 2025 is much more than a guidebook to government demolition. It is just as concerned with reconstructing the state as deconstructing it: in its pages, we find the outlines of a far-right theory of state power in which the most “paleo” forms of personal, autocratic rule rise from the scorched earth of economic libertarianism. Trumpism would revolutionize the world in order to reinvent the most archaic social structures, a lost world of racial, sexual, and class subordination. Like every project of revolutionary conservatism, it needs a new constitution and a new epistemology. Constitutional interpretation is brushed aside in favor of outright fabulation. Experimental knowledge is treated as an existential threat to power, to be replaced wherever possible by theocratic dogma and presidential edict (witness Trump’s extraordinary attack on the life sciences).

Just as surely as it wants to incapacitate the redistributive and social protective arms of the state, Project 2025 wants to exploit its vast bureaucratic powers to silence, threaten, and deport. And it intends to consolidate these powers under the personal authority of the president. The report recommends the suppression of abortion drugs and the decriminalization of protests outside abortion clinics. It calls for the militarization of the border and a dramatic expansion of migrant detention centers. It demands that ICE be allowed to use “expedited removal” against undocumented migrants throughout the country. With the arrest and attempted deportation of Columbia University student and green card holder Mahmoud Khalil, we have confirmation that Trump is prepared to go much further.

Trump’s attack on the federal security complex is the most chilling sign yet of his authoritarian intent. By purging the Pentagon and FBI of its senior officials and replacing them with concentric circles of loyalists, Trump is seeking to take personal charge of the state’s monopoly on violence, leaving him free to unleash its fire power on anyone he singles out. In short, he is attempting to build something we can genuinely call a deep state—a windowless echo chamber, as desolate as a Mar-a-Lago bathroom strewn with classified documents and inhabited by a lunatic.

Where does resistance go in the face of overwhelming assault? Democrats have contemplated a variety of legislative responses to the right-wing takeover of the Supreme Court, among them court packing, term limits, enforceable ethics oversight, and independent bipartisan review of judicial nominations. Whatever their merits, these proposals are on ice for the foreseeable future. Biden did manage to stack the lower federal courts with Democratic appointees—but this measure can only buy time as court challenges await final adjudication by the Supreme Court.

In the meantime, Democrats are rallying at the state level. Project 2025 devolves much of the responsibility for public health and emergency management to state governments, turning blue states and their attorneys general into an obvious firewall against the Trumpian onslaught. But the real issue is whether Democrats are equal to the task at hand. Republican hyper-activism has a knack for pushing liberals into a defensive position, leaving them with little choice but to mouth hollow-sounding vindications of the status quo. The defense of technical expertise and procedural norms is essential. But it is hardly sufficient as a response to a decades’ long process of attrition that has gutted the social and redistributive functions of the state and reinforced its punitive arm. Nor is it effective as a response to the revolutionary far right. Standing still is a losing strategy against an enemy that is constantly moving the ground beneath our feet.

It helps to recall a moment when the assault on the administrative state was being waged by the left, not the right. Throughout the long 1970s, left-wing activists and liberal public interest lawyers conducted an offensive campaign to occupy and transform the administrative state from the margins. Informed by the minority politics of the New Left, these activists were troubled by the narrowing of the New Deal’s initial promise: federal agencies established to monitor big business had become mere enablers of the Cold War industrial complex, fully complicit in the destruction of the environment; welfare departments across the country had imported the racist practices of the South to exclude and police the black urban poor. To counter these trends, New Left activists adopted a strategy of working “in and against” the state: that is, they sought to expand the social welfare and social protectionist horizons of the state while simultaneously weakening its powers of discipline over the poor. The liberal wing of this movement looked to the courts as a means of forcing the hand of government administrators: public interest lawyers won landmark rulings in the area of welfare and environmental law, often invoking an exalted vision of constitutional rights to buttress their claims. To their left, activists in the welfare rights and black justice movement had a more pragmatic, agonistic understanding of the power of law and remained skeptical of the cozy relationship between public interest lawyers and elite donors. In either case, their combined efforts succeeded in profoundly reshaping the scope of administrative action, forcing the state to assume new responsibilities vis-à-vis the environment, everyday consumers, the welfare poor, and racial minorities.

This history helps to clarify something about the right-wing legal movement that is routinely occluded from its own self-narration. As noted by political scientist Steven Teles, it was the left’s assault on the post–New Deal administrative state that spurred legal conservatives into action in the first place. While right-wing revisionism treats the administrative state and “wokeism” as one and the same, a closer zoom reveals a moment when the left was leading the struggle to occupy and transform government bureaucracy. The New Left treated the administrative state as a combat zone, not a neutral terrain of democratic arbitration. For a time, it managed to move the distributional battle front inside the state. It is this incursion that legal counterrevolutionaries have been fighting ever since, even when any active opponent has long since disappeared.

We are dealing with a very different state form today. The late Keynesian social state, with all its contradictions, has been replaced by the neoliberal antisocial state—a state that has downsized its redistributive functions, converted much of its welfare arm into punitive and carceral functions, privatized or outsourced as many of its services as possible, and multiplied its guarantees to private operators. This is a state form that abandons the low- and non-waged to self-care yet still includes them within its nets as permanent debtors and generators of income such as toll fees, rents, utility bills, and interest on student debt. In its most inclusive “third way” form, the neoliberal state creates “social markets” as a substitute for social insurance: that is, instead of underwriting and equalizing the risks borne by everyday citizens, it incentivizes private insurers or asset managers to operate these services at a profit. This is the impoverished social policy model that informed Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act or Joe Biden’s infrastructure and energy legislation (although we should not forget the genuinely progressive elements of both these agendas). Private health insurers and mega mutual fund managers such as BlackRock were the natural allies of this form of neoliberal capitalism.

Libertarians radicalize the antisocial proclivities of the neoliberal state. They are determined to destroy not just the last vestiges of New Deal social welfare, but even the neoliberal model of state-subsidized social markets. During the Obama years, Tea Partiers attacked the ACA’s private insurance market as if it were socialism incarnate. Under MAGA, ire has shifted to the allegedly woke BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager and a major beneficiary of the Democratic de-risking state. Trump is now threatening to abandon Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, along with all its private sector contractors. Perhaps most shockingly, he has slashed the National Institutes of Health grants that have fed the bio-pharma innovation pipeline since Reagan. It is becoming clearer by the day that the war on “woke capitalism” was more than just theater. Trump’s minions really are prepared to take down whole economic sectors—the very summits of neoliberal capitalism—to elevate their own faction of private investment partners, company founders, and controlling shareholders.

How far the war on “woke capitalism” can be pursued without provoking an all-out recession (or intra-capitalist revolt) remains to be seen. What we can be sure of, however, is that Trump’s business allies will be spared the DOGE austerity treatment. As Musk’s raid on the Treasury and Trump’s attempts to interfere with the Federal Reserve make clear, libertarians don’t actually want to abolish the state, much less the massive fiscal and monetary powers embodied in the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve. Instead, they want to drastically narrow the scope of beneficiaries to a small group of ultrawealthy private capitalists (company founders or controlling owners) and private fund managers in the world of crypto, security, real estate, and fossil fuels. This group of people is so small that we know their names; their faces are literally stamped onto their own privately issued coins, which will no doubt require propping up by the Federal Reserve in due course. Rarely has capitalist power been so personal, yet so massively inflated by the public purse.

What could it mean to work “in and against” the state today, when so many are included at one remove only, as income-generators to publicly subsidized private interests? Does it make sense to work “in and against” the state when it comes to purely punitive services such as policing and prisons? Will there be any state left to resist once Musk has completed his mission? It seems to me that we cannot afford to leave the state alone as long as we are caught in its nets as passive enablers or victims of immense wealth concentration. Musk has clarified something once and for all: libertarianism doesn’t actually liberate anyone from the state. It simply destroys the last remnants of the social state, installing in its place an intensely autocratic, patrimonial form of state rule, in which personal subordination is enforced at every level of society. Distributional struggle in and against the state remains as urgent as ever, then, even as the hybridity of current power relations complicates the question of strategy. Depending on the focus of intervention, efforts to work in and against the state may deal with neoliberal, libertarian, or residual social democratic state formations. At different levels of government, distinct policy and party regimes may be in force, making choices of scale and target an important element of any left strategy.

For the moment, federal workers are on the front lines of the Trumpian offensive. Not only do they administer programs that Republicans detest; their very status as public-sector workers in the heart of federal government (a DEI employer avant la lettre) places them in the direct line of fire. The challenges facing federal unions right now are immense. Yet their position at the nerve center of the American public sector also offers unique opportunities. The long right-wing attack on the administrative state has always relied on a widely shared indifference to the fine points of public spending. The attack could be pursued as long as people were convinced that “their” taxes were being protected from government spending on underserving others. As countless studies have shown, lower- and middle-income Republican voters live in a state of cognitive dissonance: they see their own Social Security, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits as earned income, apparently unaware that any significant cut to the federal budget would have to target these budgetary items in particular. In this regard, Musk’s willingness to raid the Social Security Administration barely a month into Trump’s presidency suggests a distinct lack of tactical foresight. The project may backfire by making things too personal too fast for too many people, including the average Trump voter.

We don’t need to look far to find a precedent for this kind of shift in public sentiment. As Eric Blanc reminds us, the long wave of public-school teacher militancy that began in 2018 unfolded under similarly unpropitious conditions. The cycle of action had its origins in West Virginia, a solidly red right-to-work state where public employee strikes were illegal. That campaign was successful largely because it refused to accept the state’s narrative of fiscal incapacity. By reaching out to parents and students as “users” of public services who stood to lose as much from funding austerity as did workers, the teachers made it impossible for the state to use divide-and-conquer tactics and effectively neutralized the legal ban on their strike action. A crucial element in the campaign was the drafting of an alternative state budget proposal, recommending an end to the state’s ultra-generous tax preferences for oil and gas firms. Having built a contestation of state budgetary politics into their campaign from the outset, the teachers were able to transform the meaning of industrial action from negotiated crisis to a genuine battle over spending priorities.

“Bargaining for the common good” describes a strategy in which workers connect their immediate wage demands to the larger distributional issues of state spending and taxation. This strategy has met with notable success in the public-sector union movement and at the level of state government. It has yet to be extended to the private sector, where the illusion of corporate independence from the state still prevails, or indeed to the federal public sector. Any scale-up to this level remains extremely challenging. Ironically, however, Musk has performed a useful service in bringing these various work sites under the same organizational umbrella.

It is obvious, for instance, that the kind of slash-and-burn tactics currently being deployed against federal workers are identical to those experienced by Silicon Valley tech workers over the last few years of mass layoffs. But beyond this, what are Tesla or X employees today if not federal workers? What are X users if not customers of a public infrastructure—the propaganda arm of the patrimonial state? When the company executive controls the levers of the Treasury, it is hard to maintain the pretense that the tech sector in any way represents the fount of private initiative, independent of government. Inadvertently, Musk has done more to highlight the commonalities between private and public-sector workers than any labor organizer in recent history. It remains to be seen how these opportunities might be exploited by an incipient Big Tech and federal worker union movement.

One important implication of the bargaining for the common good framework is that distributional struggle can arise from any facet of our daily lives in which government spending decisions play a critical role. For the past several decades, fiscal and monetary policy has sought to inflate property prices and suppress wages. The pressures have become acute since the coronavirus pandemic, as renters bear the brunt of distressed mortgages and rising interest rates. Housing tenure is increasingly salient as a factor in class stratification: wage demands mean nothing if they don’t also account for the growing portion of wages handed over to landlords. For this reason, the tenant unions that have mushroomed across the country in the last few years can be seen as a logical extension of the resurgent union movement.

One particularly promising development in this space is the adoption of tactics that look beyond individual landlords to target the government regulators responsible for backstopping their mortgages or otherwise guaranteeing their risks. In October 2024, residents in two Kansas City apartment blocks kicked off a historic rent strike that placed demands on both their landlords and the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Coordinated by the recently formed Tenant Union Federation, the strikers are demanding that the FHFA enforce rent caps and regular maintenance on any landlord that receives federal loan guarantees through Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

In the normal course of things, landlords can count on the collective rent checks sent in by residents to service their loans. The expectation of renter compliance functions as a kind of social collateral; it’s what allows the landlord to purchase the property in the first place and to hike rents whenever interest rates rise. By the same token, however, tenants can push a borrower to the brink of insolvency by collectively withholding their rent. If the loan is guaranteed by a government agency, then the state is ultimately on the hook for the money owed. It can either negotiate with renters and restructure the loan or transfer the unpaid mortgage back onto its balance sheet, thereby assuming de facto public ownership of the property in question. At this point, renters are in a much stronger position to demand that the building be maintained indefinitely as public housing. The director of the Tenant Union Federation, Tara Raghuveer, explains that the point is to oblige federal regulators to redirect their bailout and regulatory interventions in the service of renters rather than real estate developers. “Each of those interventions that the federal regulator or the GSEs [government-sponsored enterprises] might take to protect the landlord and protect their investment, becomes an opportunity for us to intervene and say, ‘Protect the tenants.’”

Although perfectly pitched for the conditions of the Biden administration, the attempt to establish federal footholds may prove harder to implement in the age of DOGE. Elsewhere, however, tenant unions have pursued similar strategies at the state and municipal levels, especially in older cities that still have tenant protection laws on the books. In 2019, a coalition of New York tenant activists helped to pass the New York State’s Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, a law that prevents landlords from serially evicting residents to evade rent stabilization statutes. In cities across California, tenant unions are pursuing a similar campaign against the state’s Ellis Act, which allows landlords to strategically go out of business in order to evict tenants. In April 2024, members of the Hillside Villa Tenants Association in Los Angeles concluded a four-year rent strike, having secured a ten-year renewal of their building’s affordability covenant. This was only a partial victory: Hillside Villa Tenants wanted the L.A. City Council to take back possession of their building through eminent domain, a goal they came tantalizingly close to achieving. Ultimately, legislative wins to cap rents and curb evictions can only be first steps in a strategy to put the powers of public money creation and debt issuance back in the hands of residents. To truly relieve the housing crisis, cities and states must be compelled to use their powers of municipal or state debt issuance to create and maintain public housing, instead of subsidizing real estate developers like Trump.

Of course, we know that Trump will crack down hard on unions and other forms of organizing, imparting a new urgency to the kinds of activism that target the criminal justice system “from below.” In a recent article reflecting on the fallout from the Supreme Court’s right-wing takeover, Amna A. Akbar urges us to refocus our attention on the lower courts, where countless people encounter the brute force of the law in their everyday lives. There is not much we can do about the Supreme Court’s overruling of the coronavirus eviction moratorium or Biden’s student debt forgiveness plan, but there is ample opportunity to intervene in the lower courts where people are deported, evicted, and criminalized for unpaid debt every day. Akbar identifies the emergence of a new kind of activism “happening within and against the courts” in the wake of protests against racialized police violence. This activism eschews legal formalism to intervene in the most material ways in the mechanics of judicial power. Its tactics extend from the ostensibly passive act of witnessing, as in court and cop watching, to coordinated actions to shut down eviction proceedings or block courthouse arrests of undocumented migrants. It includes weaponized forms of mutual aid such as collective bail funds that prevent courts from condemning indigent defendants to pretrial detention. Taken together, Akbar writes, “the protests happening within and against the courts seem connected as strategic flash points, part of a growing struggle over the value of legal process and legal equality for ordinary people — or even a rejection of the rule of law within this bourgeois democracy.”

Arguably, public defenders occupy a critical hinge position between the state, the courts, and the accused. Their employment by the state is supposed to guarantee a constitutional right to legal counsel, as laid out in the Gideon decision of 1963. Yet chronic underfunding and overwork turn them into cogs in the system, more often employed to rubber-stamp plea deals than to offer real representation to their clients. As such, the recent upsurge in unionization by progressive public defenders represents an invaluable new source of leverage in left-wing struggles against the carceral state. L.A. County public defenders were first off the block when their union, organized through the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, was recognized by the county in 2018. Public defenders in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Colorado, and New York have since followed suit. For the most part, the people driving these unionization efforts are fellow travelers of the wider movement for racial justice. They are just as concerned with fighting for structural reforms to the criminal justice system as for better wages and conditions.

In this respect, they follow the playbook laid out by the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys of New York, the first (and until recently only) unionized public defenders’ office in the country. The ALAA conducted five major strikes between 1970 and 1994, exploiting its ability to shut down the city’s court system to negotiate better funding and improved representation for clients. The union lost much of its bargaining power in the late 1990s when Mayor Rudy Giuliani established a suite of nonprofit defenders’ offices to compete with its services. It is significant then that the recently unionized Bail Project emerged out of the Bronx Defenders, one of the nonprofits that Giuliani commissioned to undermine the ALAA. When union density reaches a critical threshold, public defenders dispose of a unique weapon enjoyed by no other class of worker: by collectively withdrawing their labor, they can shut down the entire court system. If deployed in solidarity with the wider union movement, this weapon could be cultivated as an instrument to shape decisions about how and where public funds are allocated in the first place: toward carceral institutions, or toward better schools, healthcare, and social housing.

Patrimonialism is one answer to the devastation wrought by the antisocial state. It teaches subordinates that their only hope of security lies in the patronage of the boss or the landlord. All loyalty is funneled upward, and all obligation reduced to the individual or familial form of household debt. This is a state form that tolerates only one type of horizonal solidarity: that between brothers vying for the good will of the chief executive. Trump embodies this style of power like no one else. His success in reducing the Republican Party to a swarm of warring fraternities, hanging on his every word, defies historical comparison. But Trump’s mesmerizing personalism can also obscure the vulnerability of the project. For Trumpism to sustain itself as a popular movement, patrimonial relations of hierarchy and dependence must be replicated at every level of society, from the household to the workplace.

Horizontal forms of solidarity such as workplace strikes, rent strikes, and bail funds pose an existential threat to this project because they offer safety outside the bounds of clientelism. By turning individual liability into collectivized credit, debt strikes of all kinds offer an at least temporary release from the blackmail of personal dependence. These actions are valuable not just on their own terms—as punctual efforts to raise wages and lower rents—but also as incubators of a new kind of social relation. The struggle against the far right demands nothing less.

Melinda Cooper works in the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University. She is the author of Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance (2024).