Whose Homes?

Whose Homes?

Nancy Daniel’s mortgage was repackaged and sold so many times that it was unclear who actually owned the house, until she started getting letters threatening foreclosure. Occupy Our Homes Atlanta helped her fight back.

Excerpted from Necessary Trouble: America In Revolt by Sarah Jaffe. Copyright © 2016. Available from Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

“I tried for many, many years to be ‘Mrs. All America.’” Nancy Daniel said, sitting in a coffee shop in a northern suburb of Atlanta, Georgia. “I married a guy in the military and divorced him. Had two kids. Tried to do everything right, or what I was being taught was right. And it didn’t work that way. It just didn’t.” She’d greeted me with an embrace, telling me, “I’m a hugger,” although we were there to talk about a sobering subject. Daniel, like millions of other Americans, had been struggling since 2009 to keep her home.

She bought her condo in 1996, right after the Atlanta Olympics, when prices dipped to a reasonable level. “This is the first home I bought with my own money, my own credit. I was so proud of it,” she said. “I had a lot of friends help me move in and decorate and whatnot. We had a great time. It has been a wonderful place to live.”

Things started to go downhill for Daniel in the recession that followed September 11, 2001; she lost her job at a commercial refrigeration company when construction slowed and the company downsized. She described feeling shame the first time she needed to go on unemployment, as if she couldn’t support herself, but her friends reassured her that it was her money, that she had paid into the system for years. It took her over a year to find another job, a marketing and event planning position. “I thought, ‘Well, great. This is wonderful.’ Until they moved their whole marketing department to Houston,” she said.

That was in the mid-2000s, and she was getting older. Marketing, she said, is a young person’s game; it was hard to convince people to take a chance on a woman in her mid-fifties. She signed up with several temp agencies, developed an eBay business, and swapped services with people in her neighborhood, all the while remaining an active member of her condo association. She was getting by, but had to dip into her savings more and more often. Finally, in 2009, she filed for bankruptcy and reached out to Bank of America to see if she could refinance her mortgage. But in the years after the financial crisis, she was just one of millions who were struggling and reaching out individually to the big bailed-out banks for relief. “They just kind of lost me,” she said. “They stopped returning my calls.”

Like many others at the time, her mortgage had been handed off to a different company—in her case, Nationstar, a mortgage servicer. As home loans were packaged into investment securities, they were sliced and diced so many times that banks lost track of the underlying ownership. This practice occasionally ended up creating situations where banks foreclosed on a home when they no longer owned the loan, and for homeowners like Nancy Daniel, figuring out who actually owned their loan could be near impossible. For a while, she waited in limbo, not sure what was going on—until she started to get letters demanding she pay up or face foreclosure. In the fall of 2013, Nationstar began foreclosure proceedings. The banks that had created the crisis had been bailed out as a group, but homeowners like Daniel were left to struggle individually, the bailouts somehow failing to trickle down to the people at risk of losing their homes. Daniel was one of millions for whom what had seemed like a manageable level of debt—so-called “good debt,” like mortgages or student loans—had spiraled out of control when the economy collapsed.

Daniel didn’t remember how she found Occupy Our Homes Atlanta, only what it was like at the first meeting she attended. “The first thing they told me is, ‘There is no shame here. This is a shame-free zone.’ And I was full of shame. I was scared. I was begging.”

At the meeting, Occupy Our Homes activist Shabnam Bashiri welcomed Daniel, reassuring her that there was hope, that they could help. The first thing Daniel was asked to do was to write out her story and post it on the Occupy Our Homes website. “I went, ‘You mean, tell people what is going on?!?’ I was raised in a family and a culture and a society that said, ‘If you can’t pay your bills, then you are not a good person.’”

But she did it. And after her saga was published, she took a petition to a fall festival at which she was a vendor. “I sucked it up and I started asking people for signatures. I was so surprised at how many people had been in similar situations or knew people who had. I got my first, probably, two hundred signatures from the people at that festival. They were so generous, and caring, and there was no shame whatsoever. They really wanted to help. They understood.”

Occupy Our Homes Atlanta had spun off from Occupy Atlanta in the fall of 2011 as part of an attempt to connect the occupation with what was going on in the broader city. Bashiri had been home in Atlanta on a break from touring with her band when the occupation began and had thrown herself wholeheartedly into activism. “I consider myself part of this generation of people. I was excited about Obama, then really disappointed, saw something on Facebook about this Occupy thing, and went,” she told me. The park occupation was evicted after three weeks, which Bashiri thought was a good thing—“It had started to become about holding the space, and not really about what had led us to be there in the first place.”

She remembered sending out a Tweet that told people facing foreclosure to call her number. “That was on a Monday and I got a call that Thursday, from a cop. This was ironic because we had just dealt with being evicted by SWAT teams,” she said.

The police officer lived in DeKalb County and was facing a final eviction hearing the next morning; Bashiri and several other occupiers piled into a car to attend. Watching the judge sign the eviction order, she said, made the mortgage crisis real for her.

Without much further planning, they decided to occupy his house and attempt to prevent the foreclosure—and at first, they managed to stave off eviction and drew support from the neighbors. “It’s a good cause,” one of the neighbors said. “If we don’t take a stand, who will?” Eventually, the family relented under threat of arrest, though they expressed no regrets about working with Occupy. Even though they hadn’t succeeded, Bashiri thought they were on to something.

People fighting a legal battle on their own against foreclosure mostly found the deck stacked against them. Bashiri discovered, though, that for many people, facing the failure of the legal system to provide anything like justice brought them to a point where they began questioning a system that had told them that if they worked hard, they would get what they deserved. “The number of people who tried and tried and tried and as a result of just sheer incompetency and evil on the part of these banks found themselves questioning capitalism as a whole. Hardcore Republicans.” The immediacy of watching neighbors and friends struggling to keep their home seemed to transcend politics; it was more than symbolic that Occupy Atlanta’s first home battle was for a police officer. People who dismissed the park occupations as silly whining from kids felt differently when those activists were willing to risk arrest to help them save the home they’d worked hard to buy, and they began to understand whose side the occupiers were on.

Even so, it was hard for homeowners to shake the feeling of shame that they couldn’t pay their debt. Mildred Obi had always been an activist—she’d marched with Martin Luther King Jr. when she was sixteen. She fell behind on her house payments after having to leave her job on account of a disability, and in 2009, she was notified that she was in foreclosure. Like Nancy Daniel and too many other homeowners facing foreclosure, she had a hard time finding out who actually owned her mortgage, who was servicing it, and who else had a claim, and she tried to file legal claims against what seemed like a maze of banks. Despite her legal battle, she was evicted in 2012. “The same day that my personal belongings were put out on the street I received a notice from the Court of Appeals granting my motion for reconsideration,” she said.

Obi had participated in rallies at Occupy Atlanta, but at first she resisted telling the other protesters about her own struggles. “After engaging the legal system and not being able to get any justice,” she said, “you just reach out, you start hollering, you yell for everybody, anybody.”

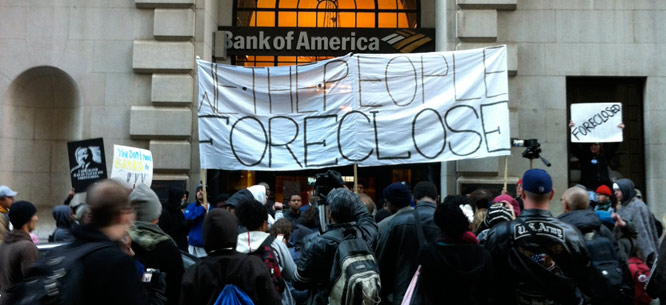

Obi moved back into her house with a group of occupiers, changed the locks, and resumed negotiating with Bank of America. At first, she said, they threatened to evict her again, then they offered to give her cash for her keys, and then finally they gave her the house back free and clear. “It’s been tough, exacerbated my symptoms both physically and mentally, but without the help of Occupy, I don’t think I would’ve had a victory,” she said. “Public outcry was important; the resistance, the persistence was very important. We had people willing to risk arrest for me. I’ll never forget that—that is close to my heart, a beautiful thing.”

As the Occupy Homes groups grew and racked up successes, they also began to coordinate on national political campaigns, joining community groups and labor unions to press for a new director to the Federal Housing Finance Agency and to push for a new law allowing homeowners to buy back their homes after foreclosure. They drew on the drama of their battles to highlight those demands

In 2013, the Occupy Homes groups decided to take their fight to Washington in an action they called “Justice to Justice.” They worked with community organizations to gather five hundred homeowners and family members who’d been affected by the mortgage crisis for a week of action in the nation’s capital that included civil disobedience outside the Justice Department. “This woman Marie, she’s from Chicago and she’s seventy-eight years old and there was this line of DHS officers in full gear, at these flowerpots,” Bashiri remembered. “They lift her up, she gets on the flowerpot, she pushes by them, and she sits down. And then all these other seniors, they’re sitting. We’re not moving!”

Bashiri was frustrated, though, by the lack of national action despite dramatic protests. The national mortgage settlements over massive fraud, she said, were too little too late, and homeowners have seen almost none of that money, which often filtered into state budgets. The grand promises turned into tiny sums. “The housing justice movement was one of the most wonderful, beautiful things,” she said. “We had so many little victories, but on a grand scale, they got away with it.”

Nancy Daniel was still waiting to see what would happen with her home. Over the past two years, she had gone through a lot. Supporters in Texas had held a protest at Nationstar’s headquarters for her, and she had sneaked into the Freddie Mac office in Atlanta—a building she describes as being like the Death Star from Star Wars—with supporters to deliver a petition to the government-sponsored entity. She had filed multiple complaints with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, among them one charging that Nationstar was illegally “dual tracking” her mortgage, negotiating with her at the same time as it was proceeding with foreclosure. She talked with people around the country who were in battles with the same servicer.

“Right now, we are waiting for something to happen,” she said. “I am looking for other places to live, but rents are unbelievable, and with my credit history it is going to be hard. I have this vision of me living in a tent under I-75 downtown. I am supposed to be comfortably retired. Isn’t that the American dream? That is not happening here.”

Sarah Jaffe is co-host of Dissent’s Belabored podcast. Her first book, Necessary Trouble, is just out from Nation Books.