President Obama and Nuclear Disarmament

President Obama and Nuclear Disarmament

A. Butfoy: Nuclear Disarmament

ON THE campaign trail in 2008, Barack Obama pledged to make the abolition of nuclear weapons a “central element” of U.S. foreign policy. The president repeated the pledge after he took office in major speeches during 2009 in Prague, at the UN, and again in Oslo while accepting the Nobel Peace Prize. Obama argued that deemphasizing nuclear weapons was not only a moral imperative but also good for U.S. national security. After all, the most obvious threat to U.S. superiority in conventional military power is nuclear proliferation.

ON THE campaign trail in 2008, Barack Obama pledged to make the abolition of nuclear weapons a “central element” of U.S. foreign policy. The president repeated the pledge after he took office in major speeches during 2009 in Prague, at the UN, and again in Oslo while accepting the Nobel Peace Prize. Obama argued that deemphasizing nuclear weapons was not only a moral imperative but also good for U.S. national security. After all, the most obvious threat to U.S. superiority in conventional military power is nuclear proliferation.

Obama was reflecting and reinforcing a wider interest in the idea of eliminating all nuclear weapons. Over the last decade, a range of former officials, experts, and international panels have called for sharp reductions in nuclear arsenals with a view to eventual abolition. Various experts argue that abolition would enhance global security, and say that a commitment to the goal is a prerequisite for nonproliferation. Advocates tend to claim that this policy shift is both increasingly urgent and feasible, and they have made predictable recommendations about how to get there.

The arms-control community has not been short of ideas, and with the support of Obama, it was hoped, the political will to make concrete steps toward abolition finally existed. Obama’s election apparently moved abolition from the margins of debate to the center stage of policy, and at a time when international backing for the idea of abolition has been offered by worthy individuals and organizations across the political spectrum. Even some hardened realists are now drawn to the idea.

Since Obama’s election, there have been signs of progress in nuclear policy. The Pentagon’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) established a more restricted role for nuclear weapons. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), passed in late 2010, reduced the size of Russian and U.S. nuclear stockpiles. Moreover, nuclear deterrence appears to have become a less salient feature of global politics. It is often seen more as insurance for an uncertain future than as a set of plans for destroying enemies.

Yet President Obama’s promise to make abolition of all nuclear weapons “a central element” of U.S. policy has run into the sand. The NPR fell short of radically redirecting U.S. strategy. The START treaty merely continued a trend established in the 1980s to reduce wildly excessive warhead numbers from the Cold War build-up. And with the Democrats’ 2010 midterm elections losses and attention spread between an ailing economy and wars in Afghanistan, Libya, and Iraq, the political space available to the president for even modest arms control has shrunken. Although Obama’s stated goal of abolition converges with considerable pressure group advocacy, there is little sign of a critical mass of either domestic or international support for prioritizing abolition. Widespread international rhetorical agreement on the desirability of abolition as a long-term objective is mostly platitudinous and disguises the reframing, rather than ending, of nuclear deterrence.

THERE ARE at least six steps that would need to be taken to get to the abolition of nuclear weapons. None of these can be taken for granted, and some look impossible:

1. A follow-up treaty to cover the thousands of U.S. and Russian nuclear warheads not cut by the new START: 1,500 deployed strategic warheads each, plus strategic weapons in storage and so-called nonstrategic nuclear warheads.

2. Full ratification and entry into force of the 1996 nuclear test-ban treaty.

3. Global agreement on a long-discussed treaty for the verifiable ending of production of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium.

4. The broadening of formal arms control to include the other members of the nuclear weapons club: China, France, the United Kingdom, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea.

5. The development of a near-universal consensus that arms control is not simply about restructuring strategic stability and reworking the idea of deterrence but should be directed at abolition.

6. A system for managing the final move to abolition. This system would need to: (a) oversee dismantlement of the last remaining weapons; (b) tackle proliferation challenges associated with nuclear energy programs; (c) verify weapons are not being rebuilt; and (d) enforce the punishment of cheaters. It would need to be far more effective than the UN and International Atomic Energy Agency.

As a package deal, even one delivered in installments, this set of measures would produce—or more likely require—a revolution in global politics. So it is no wonder that Obama has acknowledged that abolition might not happen in his lifetime. But what is standing in the way of genuine steps toward abolition?

For one, there is Obama’s generally conservative approach to policy. The president has expanded spending on both conventional and nuclear forces. Moreover, his view of America’s place in the world and the putative need to maintain and use preponderant military muscle is consistent with American tradition. Despite the Right’s shrill protests to the contrary, Obama expresses the common American view that U.S. power is, for the most part, uniquely virtuous, and guided by its superior political system. By the late twentieth century this notion had become enmeshed in the idea that U.S. strategic primacy was a reflection of the country’s righteous place in history. American primacy has been accepted by the U.S. mainstream, including Obama, as natural and essential for a well-ordered international system.

Given such a perspective, it is unsurprising that Obama believes nuclear disarmament would only be acceptable if U.S. conventional military dominance is reinforced and extended into the future. For Washington, a world free from nuclear weapons would need to be based not on an old-fashioned balance of power, and not on an acceptance of genuine equivalence between states, but on an imbalance of power entrenching U.S. primacy. Were that primacy to come under threat—with, say, the rise of China as a world power—so, too, would this path to abolition.

Yet regardless of his personal preferences, Obama lacks the political room on the home front to advance the abolitionist agenda in any sweeping way. Perhaps the best he could do is clean up some of the damage to America’s arms-control reputation left by the previous administration and steer Congress toward wrapping up unfinished arms-control business from the 1990s, like the ratification of the test-ban treaty. Congress, and in particular the Senate, is unlikely to make it easy to move much beyond these modest, but nonetheless critical, goals. Although Obama succeeded in overcoming the sometimes vitriolic attacks from the right on START, the unpleasantness and sometimes irrationality of the anti-START campaign is an indication of the sort of fight that lies in store if the president pushes much further.

In addition, the president reportedly had trouble getting even his own administration to endorse the idea that nuclear weapons should have a more restricted role. Opinion during the development of the NPR was divided over whether deterring others from using nuclear weapons ought to be the “sole” or “primary” role of U.S. nuclear weapons. “Primary” is code for the proposition that there could be secondary reasons for having the bombs, such as containing or intimidating rogue states like North Korea and Iran with the threat of a first strike. In the end, Obama’s NPR did restrict the role of nuclear weapons—for example, by banning their already unlikely use as a weapon of retaliation in response to a chemical weapon attack. However, the review explicitly declined to endorse the idea that deterrence of nuclear attack was the “sole” purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons.

In other words, Washington retains its self-proclaimed right to use nuclear weapons first, and the NPR has not moved U.S. thinking nearly as much as the accompanying publicity suggested. Obama has failed to change fundamentally American nuclear strategy. Moreover, Obama’s NPR says that any move to make deterrence of nuclear attack the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons will be delayed indefinitely and made partly conditional on the continued strengthening of the already enormous, and enormously expensive, U.S. conventional forces.

Yet universal commitment to no-first-use is a prerequisite for fundamental progress toward abolition. If the United States cannot make this commitment, it is inviting charges of muddled thinking. If Washington’s strategic policy appeared more consistent with its declarations of grandiose long-term objectives, its proclamations about abolition would perhaps be taken more seriously. But in conjunction with its assertion that American power is inseparable from abolition, it cannot but appear hypocritical.

Another reason why abolition looks unlikely has to do with the question of priorities. This is not simply about getting the global financial crisis or Afghanistan out of the way; it is likely that Americans will always think there are more pressing matters than nuclear disarmament. Abolishing nuclear weapons may or may not appeal to Americans, but there is little evidence it is considered more salient than many other issues. During good times there will be no sense of a pressing need for abolition, and in bad times a view that the weapons provide a security blanket may well be reinforced.

Some advocates of abolition think we can get there by stealth. Over time, enough small incremental measures might get us to the cusp of abolition. Then, at some stage, it would only take another relatively small but final push when circumstances are right to deliver the ultimate goal. Perhaps this idea is on the president’s mind, but he will never be in a position to make the final move. Indeed, although the new NPR reiterates Obama’s call to work toward a world without the bomb, it also declares a need to maintain the nation’s nuclear weapons infrastructure for “the next several decades or more.” In any case, there are so many excess nuclear warheads in the United States that Washington could make repeated cuts under the label of incremental disarmament while maintaining the world’s most effective nuclear arsenal for a generation or more. The actual decision between abolition and deterrence at lower force levels would not have to be made for decades.

EVEN IF Obama could get the various parts of the U.S. political and military establishments to push in the direction of abolition, he would still have to deal with an often recalcitrant external environment. Not even progressive, multilateral Europe can be relied on as an ally for the abolition agenda, as shown by the conservative stamp on NATO nuclear policy in the alliance’s 2010 revision of its guidelines, Strategic Concept. In any case, there are signs Washington would be concerned about an accelerated European move toward abolition.

Every government can be expected to have its own views on the best course regarding nuclear weapons. Indeed, there have been big differences even among different U.S. governments in similar geostrategic settings. In the 1990s the Clinton administration said the nuclear-test ban was a valuable step toward a safer world; the next administration said this was dangerous nonsense, that a ban posed a risk to national security and global order; now the White House says the ban is essential and should be ratified as soon as possible. If governments from essentially the same tradition can have such divergent views, it is unsurprising that governments from a wide range of traditions find it hard to advance a non-platitudinous collective position on arms control. For example, Moscow sees nuclear weapons as providing perhaps the only way to cling to some sense of parity with Washington. For Russia, China, Iran, and others, nuclear abolition can look like a strategy to enhance Washington’s superiority in conventional forces. In addition, these other members of the nuclear weapons club are much more at risk for traditional or conventional great-power war than the United States, and are thus more attached to nuclear weapons as a deterrent to major armed conflict. And since Obama has understandably said that the United States would keep its nuclear weapons until every other nation has surrendered its own stockpile, the most defiant members of the international community have an effective veto on his goal of abolition.

While the idea of abolition has gathered increased support in international politics over recent years, there are at least three overlapping groups of doubters and hold-outs. The first are those who consider nuclear disarmament impossible, because they believe the political conditions necessary for the project will never emerge. Second are those who think disarmament is undesirable because it would destroy deterrence, turning the clock back to before 1945 and increasing the risk of great-power conventional wars. Third are those who are uninterested in abstract debate and generalized arguments; they simply believe their own country needs nuclear weapons because of its unique circumstances.

Nevertheless, for decades most of the international community has supposedly been committed to nuclear disarmament in the form of the nuclear weapons Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which explicitly calls for movement toward abolition. But the period since the treaty was opened for signature in 1968 has seen increases in the nuclear arsenals of the officially endorsed nuclear weapons club (especially in the United States and the Soviet Union), proliferation by non-signatories (Israel, India, and Pakistan), serious violations by some members (especially Iraq and North Korea), and bloody-minded Iranian policies that might push the treaty past breaking point. Although the world is better off with the NPT than without it, experience offers little hope the treaty will provide a path to abolition. The NPT has been an inter-generational lesson to politics undergraduates everywhere on how self-interest, hypocrisy, and double standards help to define international politics.

Yet advocates usually put the NPT at the heart of the push toward abolition. Enormous hope has been pinned on a frayed idea. Although it is true that after years of treating the NPT contemptuously Washington is now trying to breathe new life into it, the results have been very modest. Some of the harm done under the previous administration has been patched up, but the United States has still to follow through on commitments made to the broader NPT membership during the 1990s, such as ratification of the nuclear-test ban. And it will have to be careful how it manages the “Indian Exception” to NPT rules, an exception engineered by George W. Bush and continued under Obama. It will take more than stirring speeches and marginal adjustments to force levels to make the NPT a credible platform for a push to abolition.

While certain individuals may have developed a sense of moral and political urgency on the issue of abolition, they lack the reach, even with Obama’s support, to generate a substantive international agreement tied to a policy of profound change. Obama recognizes he cannot determine events here, so rather than use up more of his limited political capital to force the point, he has settled on repackaging America’s nuclear deterrent. U.S. nuclear strategy now looks less reckless and more responsible. However, the pursuit of sensible arms-control measures short of abolition, rather than leading toward abolition, might be making the world politically safer for nuclear deterrence. Smaller, more safely managed nuclear arsenals might be very difficult to dislodge.

Furthermore, deterrence could become reinforced by a policy of nuclear containment. Advocates of abolition have generally argued that their cause is not simply realistic but also urgent. However, the reason for urgency—supposedly growing nuclear danger—casts doubt on the wisdom of abandoning deterrence. Never mind abolition, opponents will say, the international community is struggling to curb the proliferation dangers presented by the likes of Iran and North Korea. While abolitionists claim a logical link between moving to zero nuclear weapons and sustainable nonproliferation, the deterrence of new nuclear dangers will always take political priority over radical disarmament.

Neither the U.S. political system nor the other nuclear-armed states are ready to start the journey toward the elimination of all their nuclear warheads. While all agree that these are terrible weapons, and most say we would be better off without them, those countries with nuclear forces appear, for the most part, to be addicted to them—and they are modernizing their deterrence policies.

The president is playing out his abolitionist aspirations in the nebulous space between idealism and power politics. This space is turning out to be more politically uncomfortable than he first thought; it is not the fertile ground for sophisticated advocacy he had imagined it would be. Obama’s promise to make the abolition of nuclear weapons “a central element” of U.S. policy is going nowhere.

Andrew Butfoy is a senior lecturer in international relations and coordinator of the masters in international relations at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. He is the author of Disarming Proposals: Controlling Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Weapons.

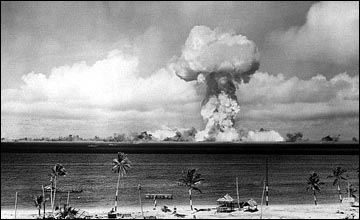

Image: Operation Crossroads nuclear test (U.S. Navy, 1946, Wikimedia Commons)