Paradoxes of UNRWA

Paradoxes of UNRWA

Dramatic recent cuts in U.S. funding to UNRWA, which provides essential services to millions of Palestinian refugees, illustrate the tensions embedded in the agency since its founding.

On January 16, the U.S. State Department announced that it was cutting more than half of its expected $125 million in funding for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). Two days later, the United States canceled an additional $45 million pledged one month prior for an emergency appeal, funds that UNRWA had already spent on emergency food assistance in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. No stranger to fiscal difficulties, the agency’s spokesperson described the move as “the worst financial crisis in UNRWA’s history.”

Since 1950, UNRWA has provided social services, healthcare, education, and other aid to Palestinian refugees. The United States is its largest funder. But American conservatives, distrustful and disdainful of the United Nations generally, harbor a particular grudge against the agency. Like UNESCO, which the United States withdrew from last October, UNRWA is for them too expensive and too anti-Israel. The Trump administration has been particularly hostile to the UN in this regard. Earlier last year, Nikki Haley, U.S. Ambassador to the UN, threatened to withdraw from the UN’s Human Rights Council if it didn’t drop Israeli human rights abuses from its permanent agenda. And in December, Trump delivered on his campaign promise to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, setting off a chorus of condemnation at the UN. The exception to the international outcry was Guatemala, whose current right-wing government announced a few weeks after the Trump decision that it would move its own embassy to Jerusalem, summoning the loyalties of Israel’s long support for Guatemala’s bloody counterinsurgency. Palestinian protests over the decision prompted Haley to threaten withdrawal of U.S. funding from UNRWA entirely, in a hardline ploy to force the Palestinian Authority back to the negotiating table for photogenic peace talks. In the United States’ grand strategy, UNRWA became just another cruelly chosen bargaining chip.

After the UNRWA cuts were announced, right-wing pundits took to the opinion pages to applaud the Trump administration’s move while feigning concern for the future of Palestine. One characteristic op-ed in the Hill was disingenuously titled “Free the Palestinians: End UNRWA funding.” UNRWA, they argued, not Israel or the United States, was the source of Palestinian destitution and the obstacle to any solution to the refugee “problem.” They reasoned that Palestinian refugees—perpetually a risk to Israel’s demographics due to their demand that they be granted their right of return—should have been permanently resettled in other countries long ago. UNRWA’s mandate to provide Palestinian refugees with essential services, in the absence of a political solution to their displacement, is seen by these critics as perpetuating the refugee problem itself.

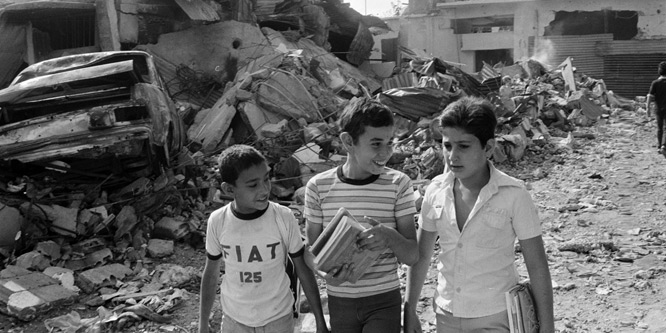

Today UNRWA feeds, clothes, and houses a people repeatedly displaced, mercilessly bombed, and perennially demonized. Even before the recent cuts, at a little more than a billion dollars a year, UNRWA’s budget was meager, given that its infrastructure and welfare programs mimic those of a small state. Its services, from the very beginning, have been supplemented by international organizations like the Red Cross and the Quakers and the generosity of neighbors, families, and comrades. Across Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon, UNRWA operates 143 clinics and hospitals. Half a million students attend UNRWA’s schools. More than a million Palestinians rely on UNRWA for food aid. Losing its funding puts these services at risk. In late January, UNRWA launched another emergency appeal to make up lost funds, an attempt to maintain its most essential services as the catastrophes pile up in these austere times.

The agency has always been tied to American money and ideas. Gordon Clapp, one of the founders of UNRWA, was previously chairman of the New Deal’s Tennessee Valley Authority, and the United States has long been the agency’s largest donor. The United States has also been Israel’s fiercest ally, regardless of how much it bombards civilians or expropriates Palestinian land, in direct violation of international law. Since its inception, UNRWA has therefore hung precariously in the balance between the pro-Israel consensus of American politics and the United States’ ostensible leadership in the “international community.”

Along the way the agency has found no shortage of critics. Some opponents see it as a quintessential example of “humanitarian management”: a peddler of aid and promises of development that stultifies dissent. Others see it as exactly the opposite, an incubator of Palestinian resistance to Israel and United States.

But UNRWA has never been simply what its detractors contend. John H. Davis, its head from 1959 to 1963, described the agency as “one of the prices—and perhaps the cheapest—that the international community was paying for not having to solve with equity the political problems of the refugees.” Davis’s frank admission, rare for an American in his position, still captures the political contradictions embedded in UNRWA today. Davis’s realization that the fortunes of Palestinian refugees were intimately tied to U.S. support for Israel is as true now as ever.

Born on a farm in Wellsville, Missouri in 1904, John Davis earned a Bachelor’s degree from Iowa State College in 1928, farming through his college years to pay tuition. He received a PhD in agricultural economics from the University of Minnesota in 1941 and worked in a variety of government agencies, including briefly as Assistant Secretary of Agriculture during the Eisenhower administration, before taking a professorship at Harvard Business School. He coined the phrase “agribusiness” in 1955 and expounded its principles in books like the bestselling Farmer in a Business Suit (1957).

In 1959, Davis was appointed Commissioner-General of UNRWA by Dag Hammarskjold. Davis requested that he be allowed to travel to Beirut, the location of the agency’s headquarters, by ship. The longer trip, he reasoned, would allow him to finish a number of books on the Middle East’s past and present, which he aimed to read before he took his post. Quite unlike many of his counterparts then, and certainly unlike the inexperienced architects of the present UNRWA cuts, Davis was not keen on flaunting his ignorance.

While Commissioner-General, Davis realized that the distribution of paltry aid to the Palestinian refugees and apolitical visions of postcolonial development would not produce a self-sufficient population. The agricultural schemes he had planned for the postwar United States had little relevance for a people largely confined to newly built refugee camps; Palestinians didn’t have a state of their own where technical solutions could be implemented. Their displacement demanded a different approach than the one he had imagined before he arrived in Beirut. These refugees had been severed from their lands and livelihoods. Many of them were farmers—a population Davis knew well—but they no longer had fields to till. Recognizing that a political solution was not immediately forthcoming, and that a generation of Palestinians could be lost without educational opportunities or viable employment, Davis’s UNRWA initiated a major expansion in its educational infrastructure and vocational training programs. UNRWA’s schools and scholarships allowed thousands of Palestinians to express their political aspirations and make their grievances known to the world. UNRWA’s teachers were legendary. Among them was the famed Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, who was assassinated by the Mossad in 1972 along with his niece Lamees.

Now, due to the budget cuts precipitated by the United States’ withdrawal of its funding, dozens of Palestinian teachers in UNRWA’s schools have already been let go. UNRWA’s free schools, crucial institutions serving the youngest and most vulnerable refugees, are under threat of closure. One Palestinian student at an UNRWA school in Lebanon summed up the irony of the present situation when she told CNN, “It’s a violation of our human rights, which America claims to teach us.”

Davis’s five-year tenure at the head of UNRWA transformed him. In his unpublished memoirs he wrote that his years in Beirut “were probably the most fulfilling years of my life, probably because I had the feeling that I was doing something worthwhile to help people in a tangible way.” Once an administrator and a “farmer in a business suit,” Davis left the crowded refugee camps an ardent critic of American policies in the Middle East.

In 1968, five years after leaving UNRWA, Davis published An Evasive Peace: A Study of the Zionist/Arab Problem. “As Commissioner-General of UNRWA,” Davis wrote in the introduction, “the writer found that the world’s understanding of the Palestine refugee problem was at variance with the truth; in several important aspects even the opposite of the truth.” He relied on scholarly histories of Israel’s establishment, like the work of the Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, and devoted much of the book to the condition of those refugees whom he had come to intimately know. Published shortly after the 1967 war, which galvanized American public support for Israel like never before, An Evasive Peace was also a cogent and prescient analysis of Israel’s media war. “The Israeli campaign of June 1967,” Davis wrote, “was by no means limited to the land, air and sea fighting in the Middle East, but was vigorously waged via the communications media of the world—particularly the Western world.” He understood the crucial role of the United States in the conflict, its importance in perpetuating the status quo.

In the final chapter of the book, entitled “The Future,” Davis made his own position abundantly clear: “As one looks ahead, the prospect of immediate peace in the Middle East is only as bright as the prospect that the United States will act promptly and decisively and bring about de-Zionization in Israel.” Fifty years later, with belligerent right-wing governments controlling both Israel and the United States, peace in the region remains as evasive as ever. Even the limited relief UNRWA provides to Palestinian refugees is now under attack.

It was said that, as UNRWA head, Davis was paid $590 a month. My grandfather, who worked for UNRWA in Gaza during Davis’s tenure, told me of a joke that circulated among the agency’s Palestinian employees: “Me and John Davis make $600 a month!” UNRWA’s mandate and global funding make it an international institution comparable to many other NGOs working with refugees and displaced people. But it is also uniquely Palestinian. In 1963 there were 11,000 Palestinian employees of the agency; today they remain the vast majority of the 30,000 people employed by the organization, which is the UN’s largest.

UNRWA’s relationship to the population it serves has always been vexed. Many Palestinians were initially skeptical of the agency’s aid. After all, the UN partition plan had played a role in turning them into refugees in the first place. In the 1950s, resistance to UNRWA was fierce, from the burning of ration cards in protest to the destruction of whole warehouses full of goods. Palestinians sometimes saw the agency’s aid as an attempt to placate them, to make them forget about their land. One Palestinian refugee told the pioneering sociologist of Palestinian life, Rosemary Sayigh, that UNRWA “intended that we should be absorbed in seeking our daily bread, and never have time to work seriously to regain our country.” They were trapped, many felt, between survival and liberation.

Yet as time went on, the camps became sites of political organizing in their own right. Palestinians in UNRWA’s camps were not and are not hapless refugees—they have established parties, garnered global support, and built their own cultural and political institutions—but they face a powerful set of forces in the United States and Israel. Today, with Palestinians expressing clear political demands—for liberation, against normalization—in refugee camps and around the world, the perception of UNRWA as an obstacle to Palestinian aspirations has less purchase. UNRWA keeps Palestinians alive, and its role in doing so has only grown with the intensification of war from Gaza to Syria. Before 2011, only some 7 percent of Palestinian refugees in Syria relied on UNRWA assistance. Today, 95 percent of them rely on the agency’s aid. Gaza’s people, two-thirds of whom rely on international assistance, struggle to survive without fuel or medicine amidst an Israeli-Egyptian blockade of eleven years and counting.

In UNRWA’s archives, the anthropologist Ilana Feldman found a petition to Davis from a group of refugees in Jordan. In 1961, they asked first for water, but more importantly told him to “inform the United Nations that we will never be able to forget our dear homeland, no matter how long we shall have to endure this miserable condition. We shall not accept any substitute for our homeland, nor relinquish it for any bribe.”

Six decades later, little has changed in the Palestinian condition. Aid is no substitute for equality. Food is not land. On January 2 of this year, Trump tweeted that “we pay the Palestinians HUNDRED OF MILLIONS OF DOLLARS a year and get no appreciation or respect.” Palestinians have received little respect since the beginning of the nakba. They have endured countless humiliations at the hands of the world’s empires, the Israeli state, their Arab brethren, and their own purported leaders. The conditions necessary for UNRWA’s demise—Palestinian freedom—do not yet exist. Until then, UNRWA keeps a captive population from starving. No respect is owed.

Esmat Elhalaby is a PhD Candidate at Rice University. He studies the intellectual and cultural history of West and South Asia.