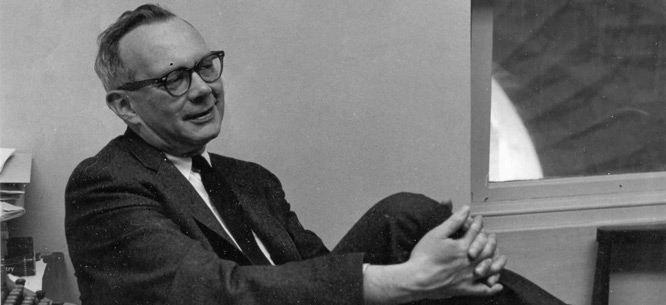

Irving Howe at 100

Irving Howe at 100

Remembering Irving Howe, the founding editor of Dissent, on his 100th birthday.

June 11 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Irving Howe, founding editor of Dissent. Today, he is remembered by Michael Walzer, Maxine Phillips, Nicolaus Mills, and Joanne Barkan. Read his work here.

Michael Walzer

For many years, before his death and after, I have been writing with Irving Howe looking over my shoulder: he is critical; I am trying to measure up. I think it all began at Brandeis University in Humanities 2 (Shakespeare to Dostoevsky), when I wrote a paper on The Tempest and Irving had “a few suggestions.” Now I have to write something to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth, and I can hear him warning me: don’t be sentimental; don’t make things up; don’t exaggerate; don’t use too many words.

Irving was a denizen of City College’s famous Alcove One, a leading member of the New York Jewish intellectuals (think of the Bloomsbury Group or the Southern Agrarians, which included John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren), a brilliant literary critic, an astute reader and promoter of Yiddish literature, a teacher greatly admired by his students, a graceful writer, and a genius editor of other people’s prose. None of this, he tells me over my shoulder, is what I should write about. Okay then; here is what I have to say.

Irving Howe stood in a long line of socialist writers and militants, from Emile Zola and Jean Jaures to Randolph Bourne and Eugene Debs. How he stood is best illustrated by two moments in the early years of his political life. In the days when New York was a suburb of Moscow, he was one of the dissidents, defending freedom and democracy against Stalinist repression and its local apologists. But when Joe McCarthy and other right-wingers turned anti-communism into a repressive politics, he defended the civil rights of the men and women he had spent years attacking. He understood that the struggle for democracy and equality required him and his friends to fight always against opponents on the right and often, too, against opponents on the left.

He came out of the Trotskyist sects, together with a few friends, to forge a new kind of democratic socialism. His commitment, and theirs, was chastened, skeptical, ironic, and at the same time strong and deep. To express this commitment, he and his friends founded a magazine, this magazine, and editing Dissent became his life’s work.

He worked at it not like an intellectual but like a worker. He raised money, recruited editors, found helpers of many sorts, hunted for writers, suggested subjects, edited copy, held all the editors, writers, and helpers together. No one expected it, but he was a skillful diplomat; there were no splits, no angry resignations. He and his friends kept in touch with democratic socialists around the world, in every European country, in Latin America, in India and Israel, in Algeria and Vietnam. Magazines abroad reprinted articles from Dissent; their editors often thought that not paying for them was an act of socialist solidarity.

Money was always a problem. Initially, Irving did not think that the magazine would survive for more than a few years. But it was frugally run; no writers who had anything resembling an income were paid, the office was a friend’s living room. And Irving found people in the next generation and then in the generation after that who were attracted by Dissent’s version of democratic socialism—his version and that of his friends.

It is our version now; readers will know it well. It requires a persistent critique of all the inequalities produced by capitalism here at home—and also of all the inequalities produced by authoritarian leftists abroad. It requires fierce opposition to every sort of high-and-mightiness, to corporate arrogance, vanguard presumption, and the claims of Maximal Leaders. It means that greater social and economic equality have to be achieved, can only be achieved, through democratic struggle, that is, through the exercise of the essential political rights: the right of opposition, the right to organize parties and unions, the right to speak, publish, assemble. Finally, it means that the work we have to do, the criticism, the opposition, and the struggle will go on and on; the revolution isn’t going to happen or if it does, it may well end in terror and repression; new inequalities will emerge and new tyrannies. But there are always important gains for humankind within our grasp. Socialism, Irving wrote, is steady work.

Looking over my shoulder, he says: about this article, Michael, I have a few suggestions . . .

I say: Listen, Irving, this article is going to be published in Dissent magazine in the year 2020. You should be amazed, heartened, and proud.

Maxine Phillips

When he died twenty-seven years ago, Irving Howe was a few months younger than I am now. He seemed like an eminence grise to me then, certainly old enough to have been my father, though definitely not fatherly. I’d met him in the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC), which he, Michael Harrington, and others had founded. When he was among those who interviewed me for the position of managing editor for the organization’s monthly publication, his verdict had been, “Qualified, but too nice to be an editor.” I responded in my first week on the job by rejecting one of his articles. We got along.

In those early days, the late 1970s, I respected him for having been a mentor to Michael Harrington. Still, wasn’t he a social democratic dinosaur, oblivious to social movements, and, to judge by the lack of women writing for his magazine, clearly sexist?

What I came to respect even more was his unswerving commitment to the cause, the “steady work” he so often wrote about. He may have started his socialist career as a teenage proselytizer standing on a soapbox, but even after he became famous, he rarely turned down the chance to persuade one more person to the cause. As a new member of my local DSOC chapter, I’d thought nothing of inviting this National Book Award winner to speak to twenty-five recruits at a rundown church camp two hours out of the city—on a weekend, no less. In fact, I thought he’d been too persnickety in insisting on a private room. All irritation vanished as soon as he started speaking of his vision, of a world with enough for all, with a vastly fairer economic system, with democracy in every aspect of our lives. Yes! This was why I and others had joined the movement. This was a story I could listen to—and have—for the rest of my life.

He never lost sight of that vision. When DSOC merged with the New American Movement to become Democratic Socialists of America, purists in both organizations left. The synergy we’d hoped for didn’t materialize right away. Elders from both organizations hit the road for unity speaking tours, despite their distaste for sharing a stage with one another. Now that DSA is bigger than either Harrington or Howe dreamed of, and riven more ways than they could have imagined, but still gathering under a big tent, Irving’s ability to keep that overarching vision in sight still inspires me.

Today, I’m occasionally one of those elders on a panel with people whose political approaches I don’t share. The DSA banner hangs behind us, a colorful reminder that we now represent what’s left of so many strands of the socialist ideal. When I re-read my go-to essay of his, originally a speech at some long-ago event, I think, it could have been written today. “The socialist idea,” he writes, “is no longer young, no longer innocent.” But, he sees, in the last decade of the last century, “a new wave of social energy,” and urges his listeners to understand how hard the path to socialism is in a country that has, perhaps, been the most hostile to it.

“Here we have to join with everyone who is ready to fight for a little more now,” for the things like healthcare, housing, full employment that “patch up an unjust society.” At the same time, we “have to say that these things are inadequate.”

And to “say both kinds of things, to say them at the same time, to keep a balance between the near and the far—that’s what it means to be a socialist in America.”

Nicolaus Mills

It is hard for me to imagine that June 11 will mark Irving Howe’s 100th birthday. I always thought of Irving as someone older than myself who would never grow old, and never be more than a phone call away.

The first time we met was in the mid-1970s at a party I was brought to by a friend of the host. I had been writing in Dissent for a few years by then, but I had never spoken directly with Irving. During that time Irving had published a long excerpt from a diary I kept while working as an organizer for Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers, and I thought of him as my editor, not a friend.

I knew what Irving looked like, and I waited for the party to thin out before I introduced myself. For a while we made small talk. Then somehow our conversation turned to Tom Seaver, the New York Mets pitcher, who at the time was at the peak of his career. Irving had grown up in the Bronx as a Yankees fan. He had even seen Babe Ruth play. But in a one-man protest against the perpetual demeaning of Yankees players by the team’s owner, George Steinbrenner, Irving had switched his loyalties to the Mets.

I don’t remember what either of us said to steer our conversation to Tom Seaver, but the idea that socialist ethics could extend to baseball ownership was to me a delight. It was also a window into Irving. Socialist principles were such an integral part of his life that it was as natural for them to include baseball as politics and literature.

When I joined Dissent, it still often functioned like a mom-and-pop operation. The magazine’s office was Stanley and Simone Plastrik’s Upper West Side apartment, and I often carried manuscripts to Irving’s East Side apartment during my daily run in Central Park. Such economies were always a reassurance to Irving that Dissent had not strayed from its proper roots.

“When intellectuals can do nothing else they start a magazine,” Irving wrote about the founding of Dissent. The remark came to be viewed by his critics as an admission of futility, but the opposite was the case. Years earlier Irving had broken with those on the left who had turned a blind eye to Stalin’s tyrannies. In founding Dissent in 1954, he also broke with a much larger group of writers and intellectuals who had grown increasingly conservative in the wake of the right-wing demagoguery of Senator Joe McCarthy.

I was too young to have known firsthand Dissent’s beginnings, but I understood how lonely and difficult they had been. Whenever Irving met with the writers and editors who had been with him from the start, there was a special tenderness that came over him. They were his band of brothers.

When Michael Walzer succeeded Irving as Dissent’s editor, the changing of the guard was natural: Michael had been Irving’s student at Brandeis. Now Dissent is in its the third iteration. I think Irving would be a happy reader of today’s magazine, finding in it the vision he and Lewis Coser, another founding editor, put forward in 1954 when they wrote, “What socialists want is simply to do away with those sources of conflict which are the cause of material deprivation and which, in turn, help create psychological and moral suffering.”

In the era before email and Twitter, Irving had his own version of shorthand communication: the postcards he continually sent to writers with suggestions and criticisms. I foolishly never kept my postcards, and most Dissent writers I know never kept theirs. We took them for granted. But the postcards were Irving’s true notebooks, his day-to-day record of what it took for him to hold Dissent together.

One of Irving’s greatest challenges in editing the magazine was making sure it did not become a mere academic outpost. In that undertaking he had the advantage of never having had to recover from years spent writing a PhD. His natural instinct was to seek out general readers.

At Irving’s behest I covered labor strikes at the Hormel meat plant in Austin, Minnesota, and the A. T. Massey coal mines in Kentucky and West Virginia. It was the writing I did that pleased him most. It was straight reporting. The only thing he ever questioned me about was how I got by averaging under $7 a day for meals.

“I stumbled into socialism,” Irving wrote in his autobiography, A Margin of Hope. That stumble at age fourteen was his fortunate fall. It gave Irving a lifelong empathy with a variety of stumblers. Irving was suspicious of anyone who saw progress as a straight line rather than a zigzag, and he had a high tolerance for quirks and inconsistencies. Dissent under his editorship had a distinct voice—but never a party line.

Joanne Barkan

How did Irving Howe treat women intellectuals at Dissent? This was a strange question to ponder given that I consider Irving a treasured friend, mentor, political comrade, and—apart from my husband—the strongest supporter I’ve ever had. But ponder I did after Ronnie Grinberg, assistant professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, asked to interview me about Irving and women at Dissent as part of her research for a chapter about him in her book, provisionally titled Write Like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals.

I worked with Irving at a time—1985 to his death in 1993—when not just Dissent, but most political magazines, had few women on their editorial boards or among their writers. When my first Dissent article appeared in the Spring 1986 issue, the editorial board counted nine women out of forty-one members; the table of contents of that issue listed six women out of twenty-seven authors. The other magazines were worse: in issues released the same month, the New Republic listed one woman out of fourteen authors; the Nation, one out of eleven; the National Review, one out of sixteen; the Atlantic Monthly, two out of seventeen. At every Dissent board meeting I attended for the next decade, one or two members brought up the need to recruit more women. Irving usually answered, “Give me names.” The discussions usually circled down to “we’ll attract more women when Dissent publishes more good articles relevant to women, which requires finding more women interested in writing for Dissent.”

No one obsessed more about the need to involve new people than Irving, and no one recruited more consciously. Women or men? It didn’t matter. He was fixated on maintaining the quality of the magazine while improving its chances of survival after he died. He and the other founders had launched the magazine in 1954 when they were in their thirties and forties. Now they were “seniors.” Irving wanted to find younger people who would commit to Dissent with a lifetime of “steady work,” write regularly, sustain the magazine’s “democratic socialist vision,” and help with the workload. Anyone he thought wrote well and, as he put it, “had an idea” got his enthusiastic support and solicitude. He had a method: if he noticed your work and liked it, he would invite you for coffee or lunch to talk politics, ask you to write something for the magazine, suggest you come to a Dissent board meeting, where there was always a political discussion after the business agenda. The process was exactly the same for women and men. It grew out of the Dissent ethos of familial political camaraderie that went back decades. After Irving and I became friends, I said to him, “You’re really an organizer.” With his slightly sly smile, he said, “in my own way.”

In my experience, Irving treated women and men intellectuals equally and in the same idiosyncratic manner. He had high standards and an impatient manner, but he applied these equally to women and men. He directed his most dismissive criticisms—“He hasn’t had an idea in his life”; “She’s not serious”; “He’s terribly slipshod” (a Howesque word I loved)—to both sexes. If you made a commitment to Dissent, his solicitude only increased. He regularly “made the rounds” as some of us called his way of meeting for one-on-one lunches or dinners with both “younger people” and his lifelong comrades. He assumed Dissent was and should remain haimish even as the “family” evolved.

Irving urged me to write longer and “more ambitious” pieces, to do “some serious reading.” About cutting an article he thought was too long, he’d say, “Be hard on yourself.” He occasionally edited a piece of mine while I sat at the same table. Watching him advance through a manuscript with his black pen and unstoppable focus was awe-inspiring and a bit scary. When I objected to a cut, he once said, “You’re critical of other people’s writing, but you don’t want your own changed.” I countered, “You’ve always told me that a serious writer fights for her writing.” With that sly smile he replied, “But she doesn’t always win.”

I look back on every moment I spent with Irving as precious (well, almost every moment; he could also be startlingly curt). I’m grateful for the question about his treatment of women because it plunged me into days of remembering. I emerged feeling joyful, lucky, and bereaved. I’ll always miss Irving.

Michael Walzer is editor emeritus of Dissent.

Maxine Phillips, a former national director of DSA, retired as executive editor of Dissent and is back at her first DSA job, this time as a volunteer, as editor of DSA’s quarterly Democratic Left.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.

Joanne Barkan is a writer and longtime Dissent editorial board member. She covered the negative effects of “Big Philanthropy” on democracy during the last decade and writes ekphrastic poetry in collaboration with several women artists.