China’s Surveillance Laboratory

China’s Surveillance Laboratory

Reeducation camps, mosque monitoring, an extensive network of security checkpoints—these are just a few features of the surveillance apparatus China is developing to police Uyghur Muslims. A report from Xinjiang.

Muslims in northwest China’s Xinjiang, the Uyghur homeland, endure a constant barrage of state-sanctioned violence. For hundreds of thousands of people, that violence comes in the form of incarceration in “reeducation” centers for which officials just recently attempted to provide legal justification. Those who have been spared this fate have not escaped the state’s assault on their freedoms. Although they are not confined to the reeducation compounds lined with razor wire, they are nonetheless subjected to institutionalized Islamophobia and omnipresent surveillance.

At night, Ürümchi, the region’s capital, pulses with red and blue lights. In the city’s Uyghur districts, “Convenience Police Stations” bristling with face-recognition cameras stand sentinel every 200 meters. Checkpoints are everywhere. Cameras, gates, face-scanning machines, and metal detectors at the entrance of every residential area, shopping center, and large place of business have turned the city into a high-tech labyrinth where only people with the right faces and passbooks can move without running into walls. The city is a giant police lab where Muslim minorities are treated as test subjects in an anti-religious experiment. The walls, gates, and police are part of an attempt to eliminate unwanted forms of Islamic practice.

State officials began this experiment in urban authoritarianism over nine years ago, on July 5, 2009. That morning, hundreds of Uyghurs carrying Chinese flags demanded Communist Party leaders protect the rights of Uyghurs who had been sent to work in factories in South China. The protest was met with police violence and soon spiraled into interethnic bloodshed. According to official figures, the protests and ensuing violence claimed 197 lives and resulted in close to 2,000 injuries. In the following weeks hundreds, if not thousands, of Uyghur young men were disappeared by the state. They have never been seen since.

Violence did not end on Ürümchi’s streets that July afternoon. This decade has witnessed increasing incidents of sporadic violence in the region, and it has spilled into Beijing and Kunming. Between 2013 and 2014 alone, as many as 700 people were killed in police raids, assassinations, and skirmishes with security personnel.

The region’s protracted spiral of state oppression and Uyghur resistance raises questions about the future stability of the region itself. Despite state claims that Xinjiang has been an inalienable and “multi-ethnic” part of China “since ancient times,” many Uyghurs insist their language, religion, and culture are under assault and complain of exclusion from China’s booming but Han-dominated economy through forms of systematic, institutionalized bias. Uyghur people we interviewed said the region’s violence proceeds from experiences of loss and injustice, not from ideological motivations. Processes of dispossession are pushing Uyghurs to a breaking point. And yet the state clings to its well-rehearsed script, which holds that improving the Uyghurs’ material lives through market development while eradicating “extremism” will bring stability to the region.

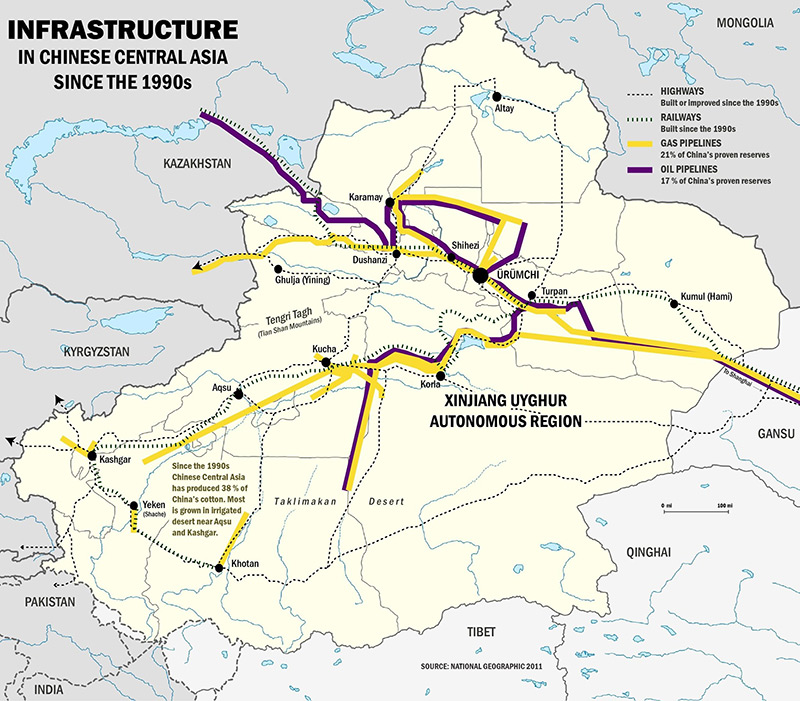

Economic development provides the greatest immediate benefits for those who already possess social and cultural capital. Because of this, China’s approach to development has transformed the Uyghur’s homeland while destabilizing it in the process. Land reforms and labor-transfer programs began a process of Uyghur dispossession. The buildout of trains, highways, and 3G mobile networks catalyzed a widespread turn to more pious forms of Islamic practice. These unintended outcomes prompted the state to redouble its efforts to eradicate “extremism” while accelerating a new form of development: turning China into a counterinsurgency policing superpower.

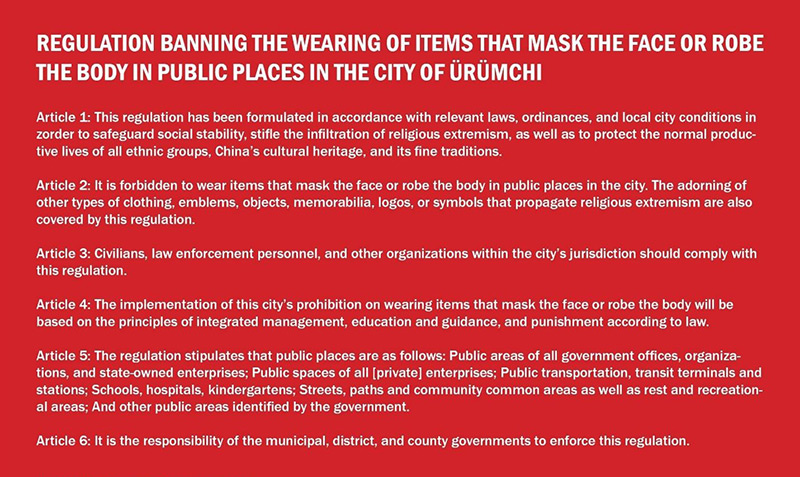

This vast and invasive form of securitization arose in 2017 when Xi Jinping urged the construction of a “great wall of iron” to protect the region from what Chinese leaders consider a threat to the territorial integrity of the People’s Republic. Shortly after Xi’s remarks, on April 1, 2017, the Communist Party announced the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s Articles on Eliminating Extremism. This legislation’s definition of extremism includes any action that “misrepresents religious teachings to incite hatred, foment discrimination, and advocate violence.” The document further identifies fifteen unlawful “manifestations of extremism,” including refusing “non-halal brands,” refusing to watch state television, and wearing “extremist symbols” such as unauthorized veils or beards. The law signals the state’s reshuffling of the so-called “three forces” that threaten social stability: religious extremism, ethnic separatism, and violent terrorism. It now prioritizes eliminating extremism over the all else.

“Extremism,” like the other two terms, does a great deal of work for the state. The term is descriptive and prescriptive. It labels certain behaviors abnormal, deviant, unacceptable, and outside of the mainstream, while justifying the policing of norms and, in turn, the imposition of new norms and forms of control. Although the document’s precise ordering presents a semblance of exactitude, its ambiguous legal jargon and ad hoc enforcement reflects an institutional Islamophobia that drives the policing of Islamic practice. Instead of identifying and clarifying the meaning of extremism, as Xinhua News claims, the law and corresponding campaign obscure the already hazy line separating legal and illegal religious practices in Xinjiang while at the same time empowering local officials to punish Uyghurs for anything deemed deviant or abnormal.

State officials believe Islam has “sickened” the Uyghurs and regard their piety as a serious threat to Chinese national sovereignty. At a 2016 conference on religious affairs, Xi Jinping encouraged the fusion of “religious doctrines with Chinese culture,” remarks some believe are directed against alleged “Islamization” movements—or Islamic practices and beliefs that have not been “Sinicized” by Chinese culture or Confucian ethics. Earlier that year, state leaders ditched legislation that would have regulated and monitored the production of halal food after some influential scholars in China criticized the law for violating the separation of religion and state; Wang Zhengwei, a Hui Muslim advocate for the bill who also held the highest position in the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, was dismissed from his post shortly after the decision. These events came against the backdrop of a rise in online anti-Islamic slurs by Han netizens, an alarming situation considering the state’s strict censorship of any comments that may incite ethnic hatred and create political unrest.

Ürümchi: A Center of Xinjiang’s Police StateSince 2014 Ürümchi has become the nerve center of Xinjiang’s police state. This lengthy and expensive process required an overhaul of the city, complete with large-scale urban development projects, population relocation, high-tech surveillance systems, and conspicuous propaganda campaigns aimed to “civilize” the autonomous region’s capital. Although Ürümchi was not a cultural or intellectual center for Uyghurs historically, when Uyghur migrants began to arrive in the city in large numbers in the 1980s and 1990s they transformed sections of the cityscape into native or “yerlik” spaces, much like other cities in Xinjiang. Because of this, and the violence the state associated with the populations living in these spaces, the state determined that it must re-engineer them—a process Jay Dautcher calls “desettlement.” Uyghur social practices and forms of knowledge are cordoned off, identified, and replaced with new norms and practices. If devotion to Allah stood at the center of Uyghur life in the past, the Party and its leader Xi Jinping must become the center of Uyghur life under the new regime. The end goal, what the state refers to as “permanent peace,” is to tie Ürümchi—its aesthetics, culture, and values—more closely to Beijing.

Recent development projects are wiping away the few traces of Uyghur culture left in the city. Authorities began their work shortly after the 2009 riots, when they announced the demolition and reconstruction of the city’s “shantytown” districts, such as Heijiashan and Yamalikeshan. At the time, these districts were home to between 300,000 and 500,000 people, most of whom were Uyghur. The citywide, $41 billion urban renewal project targeted communities with homes said to be poorly constructed and without utilities, and with inhabitants who were allegedly prone to crime. In their place, and in locations farther from the city’s center, urban planners built 361 red and yellow high-rise apartment buildings. Those who could prove they had a legal right to the city could buy these new, bare concrete apartments at subsidized prices. Many Uyghurs were forced to leave the city or move into rental properties in other parts of the city due to these urban renewal projects. Nearly a decade later, most of the new housing in Heijiashan remains vacant. By constructing dozens of residential compounds typical of recent construction elsewhere in China where tightly nestled Uyghur courtyards once stood, city planners have made the city easier to govern by transforming it into a smoothly designed space with enclosures, gates, and cameras.

When completed, Ürümchi will in many ways resemble every other mid-sized Chinese city. To this end, authorities have not spared any details. In commemoration of the sixtieth anniversary of the formation of the Xinjian Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), officials undertook a citywide lighting project to illuminate Ürümchi’s major roads and sixty-five buildings of interest. Beneath each street lamp hang three red lanterns, which are ubiquitous in Han Chinese culture. Such lanterns might seem festive, were they not hung in a city where one the main Uyghur neighborhoods, Heijiashan, is flanked by a military base and flotillas of armored vehicles patrol the streets.

Population ControlAlthough Ürümchi’s physical transformation has been dramatic, the success of the urbanization project depends on the authorities’ ability to carefully monitor and control the city’s population. With approximately 2.5 million people, Ürümchi is one of the largest cities in western China. At nearly 73 percent of the city’s total population, Han people predominate, while Muslim Uyghur and Hui people make up 13 and 10 percent respectively. Despite Ürümchi’s diverse composition, the city is segregated along ethnic lines. Over 45 percent of Ürümchi’s Uyghurs live in the Tianshan District, one of seven districts, located in the city’s center. Five sub-districts of Tianshan have Uyghur populations of at least 23 percent.

In addition, as many as 300,000 Uyghur migrants from southern Xinjiang’s rural oases made Ürümchi their home before 2017. Many came to the city because jobs were more plentiful and security, at least compared to southern Xinjiang at that time, was less strict. An estimated two-thirds of Uyghur migrants were men, with a median age over thirty; over one half of Uyghur migrants had not completed high school. This group was particularly vulnerable to employer discrimination and economic disparity, especially compared to the city’s Han migrants. However, many remained in the city, finding work in restaurants, selling snacks from roadside stands, and peddling consumer goods, all while constantly dodging security personnel.

The temporary implementation of the “People’s Convenience Contact Card” program exacerbated the precarity of Uyghur migrants in Ürümchi. Introduced on May 1, 2014, and officially described as a means of “effective, reasonable and lawful management of Xinjiang’s floating population,” the campaign required all persons over the age of sixteen to carry an identification card (in addition to the standard resident ID card) containing their legal name, ethnic status, telephone number, and a contact person (usually an official from their hometown) during travel outside the county where they were born. This screening mechanism, scanned at every security checkpoint, allowed authorities throughout the region to keep close tabs on the whereabouts of “problematic” people. In order to receive this card, however, individuals were required to return to their hometown and apply at their local police station. The majority of Uyghurs were not given the card when they applied for it upon their return to their hometowns and, as a result, were not allowed to leave their home counties. During this period, many Uyghurs told us that life in the countryside began to resemble an “open-air prison.”

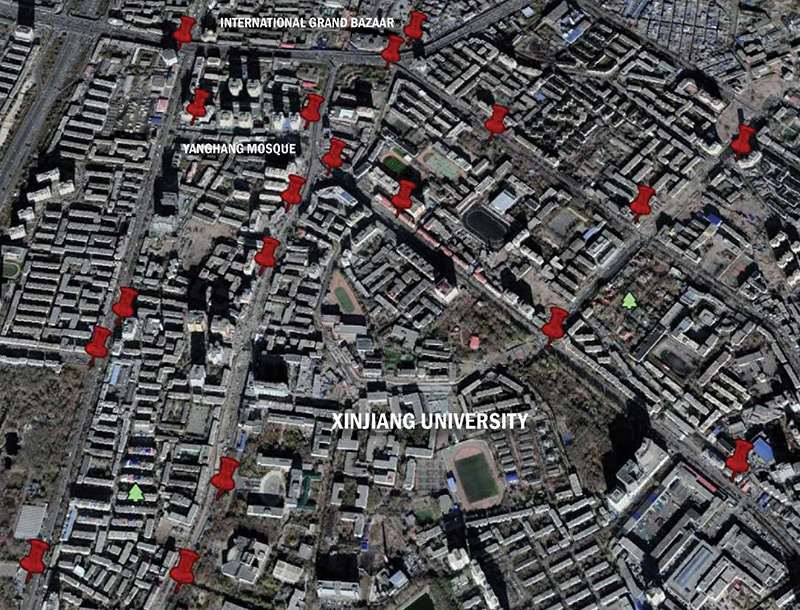

Although state officials canceled the People’s Convenience Contact Card campaign on May 1, 2016, they immediately replaced it with security measures that are even more invasive. Currently, every resident is designated as “safe,” “normal,” or “unsafe,” based on metrics such as age, faith, religious practices, foreign contacts, and experience abroad. In 2017, Xinjiang’s Party Secretary Chen Quanguo introduced a network of over 7,500 “convenience police stations,” described as “street-corner bulwarks for community based policing,” a policy he had implemented in the Tibet Autonomous Region during his tenure as that region’s Party Secretary. Based on our 2017 measurements, “convenience police stations” now tower over intersections and sidewalks and cast shadows over mosques every 200 meters in Ürümchi’s Uyghur districts. Authorities boast that the “zero-distance proximity” of stations ensures twenty-four-hour surveillance and swift responses in the event of emergencies.

A map of “convenience police stations” in the center of the Uyghur district in Ürümchi (Darren Byler, with Google Earth)

A map of “convenience police stations” in the center of the Uyghur district in Ürümchi (Darren Byler, with Google Earth)Convenience police stations serve as hubs for the region’s new facial-recognition technology. Similar to its predecessor, the People’s Convenience Contact Card, Xinjiang’s facial-recognition system monitors and records human movement, but at a much faster pace. The new high-tech system is designed to notify authorities as soon as suspects stray more than 300 meters from their homes. With this technology installed, security cameras process images from an extensive database of persons of interest, mostly Uyghur men. The technology makes video searchable, allowing police enforcement to query the location of anyone who has passed in front of their cameras at any time.

This extensive surveillance apparatus demands a strong paramilitary and law enforcement presence. In the second half of 2016, the months in which construction began on the city’s convenience police stations, Ürümchi’s local government advertised 8,000 new police positions. Authorities announced another 2,700 law enforcement positions between January and August 2017. However, the recruitment numbers for Ürümchi represent only a small fraction of the total for the province: openings for 100,000 security personnel were advertised throughout Xinjiang during this same period. These officers monitor their station’s cameras and conduct spot checks of IDs and smartphones of young Uyghurs. They stop pedestrians and cars, looking for people who do not have a legal right to be in the city or are violating religious regulations. They look for people registered in rural villages and who lack work-authorization documents. They also look for signs of Islamic piety in both the appearance of the young Uyghurs and on their phones. At times, authorities use scanning devices and applications to detect Islamic symbols in images and banned words, such as “Allah” or “Khuda,” in texts.

Engineering Uyghur-Chinese CitizensUnder the watchful eye of thousands of security personnel, Uyghurs left in the capital are coached to become “civilized citizens.” The first step in this process was forcing Uyghurs to embody Han or secular modes of dress.

Modes of dress the state deemed examples of “extreme” or “foreign” Islam became the campaign’s first target. To curb “extremist” Islamic dress, especially imported styles of veiling, authorities in Xinjiang launched “Project Beauty” in September 2011. The initiative requires women to shed face veils, hijab, and long robes while promoting “modern fashion,” represented by free-flowing hair and colorful ätläs fabric. Officials in Ürümchi ramped up their efforts to de-veil Uyghur women by passing of the “Regulation banning the wearing of items that mask the face or robe the body in public places in the city of Ürümchi,” which went into effect on February 1, 2015.

In subsequent years, this “de-extremification” campaign flooded the city’s airwaves. China National Radio’s Uyghur-language broadcast regularly aired the following public service announcement emphasizing that Uyghurs should wear traditional Uyghur clothing deemed non-extremist (translation follows):

“Grandma, Grandma! It is windy outside. Make sure you tie your veil tightly. Mother, your shirt looks so good on you. Why doesn’t my atlas shirt look like yours?”

“My child, take a look at yourself in the mirror. Your doppa [hat] looks good with this type of shirt.”

“When can I dress like you?”

“When you get older like me, then you can pick colorful atlas cloth like this and wear a style that matches the times…”

[Narrator:] “Friends, are you listening? Our ethnic clothing has been handed down to us by our ancestors and should be cherished. It is a splendid testament to our identity. Therefore, you shouldn’t forget the importance of combining traditional clothing with modern clothing for our future development.”

Officials did not limit their ban on sartorial practices to Islamic veils. In 2015, officials identified the “five abnormal types,” a designation that also includes inappropriately long beards and clothing bearing “Islamic symbols.”

A Project Beauty poster that was posted throughout the Uyghur neighborhoods of Ürümchi at the beginning of the People’s War on Terror.

According to local officials, violations of this dress code “flagrantly interfere with the ordinary lives of the masses.” In a 2015 interview with Phoenix Online, Xiong Xuanguo, then secretary of XUAR’s Standing Committee of Politics and Law, justified the ban on five grounds. His first justification was doctrinal: although not an Islamic jurist, Xiong maintains beards and veils are not mandated by the Qur’an. He then provided a cultural rationalization: these appearances run counter to Uyghur “traditional” sartorial culture. How, Xiong asks, can an ethnic group with a tradition of singing and dancing dress in such a way? Xiong also presented a medical explanation, claiming that veils are detrimental to the health of women, putting them at risk of respiratory tract infections and skin diseases. Finally, he noted, the ban in Xinjiang follows similar restrictions already enforced in France, Egypt, Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Syria.

As Uyghurs’ appearances become less “Muslim” and conform to mainstream Han standards, the state has begun to focus on weakening their faith. To this end, officials continue to step up mosque surveillance. On November 11, 2016, city authorities published a document titled “Strengthen Ürümchi Education Management Services for Mosque and Religious Activities.” According to these new guidelines, officials must deepen their understandings of the persistence, complexity, mass appeal, ethnic nature, and global connections of Xinjiang’s religions, and they must unite clerics and believers closely with the state.

Chinese flags wave in front of Hantängri Mosque in the Nanmen neighborhood of Ürümchi (Timothy Grose)

Chinese flags wave in front of Hantängri Mosque in the Nanmen neighborhood of Ürümchi (Timothy Grose)In practice, the unity the document alludes to has meant increased security personnel near mosques. Faithful entering the Yanghang and Dongköwrük mosques, two of the city’s largest, have to pass through face-scanning turnstiles and metal detectors. In 2017, during the Eid al-Fitr prayer marking the end of Ramadan, worshippers at the Yanghang mosque were forced to gather around the flag and sing the national anthem; the morning’s khutbah (sermon) encouraged the congregation to be patriotic citizens. These practices and messages have been repeated on a regular basis across the city. Since the fall of 2017, many Uyghurs have stopped attending mosque services altogether.

Filling the Void with Han Cultural NormsWhile the state is eliminating Islamic elements of Uyghur social life, it is replacing them with norms and practices common to mainstream Chinese society, beginning with the promotion of the national language, Chinese, in education, law, and commerce. Ürümchi has become the testing ground for sweeping language reforms that privilege Mandarin before extending them to southern Xinjiang. To be sure, both China’s Constitution and the Law of Regional Ethnic Autonomy protect the rights of minority ethnic groups to “use and develop” their native languages. However, the Uyghur language has steadily become subordinate to Chinese, especially in the realm of education. As early as 2004, all schools in Ürümchi adopted a Chinese-language only policy.

Even the region’s Uyghur-language television channels encourage viewers to speak Chinese. A tickertape that runs periodically on Xinjiang Television Channel 5, an Ürümchi-based station, broadcasts these messages to the region’s Uyghur speakers:

- Speak the national language fluently. We can make friends everywhere.

- The national language is our language in schools.

- Spread the national language; let’s be like members of the same family.

- When we speak the national language, our lives are brighter and society more harmonious.

To be sure, many Uyghurs recognize the importance of learning Chinese and want to learn it. But they also crave formal instruction in their mother language. A college-educated man in his late twenties remarked:

The government says it is giving [Uyghurs] an opportunity to learn another language, and we [Uyghurs] should be happy because learning languages is a good thing. That’s not the point. Of course I want to learn Chinese. Without it, I wouldn’t be able to find a job. But I want to study my own language too.

Considering the emphasis placed on Chinese, some of our sources even grimly predicted that Uyghur children in the not-so-distant future will become monolingual speakers.

Fluency in Chinese is the first step towards state-defined Chinese “civilization,” but the entire project requires Uyghurs to adopt an entirely new set of values. Signs in the form of Han folk art on buildings, the walls of underpasses, and even inside taxis remind Ürümchi’s citizens of “our [i.e., Chinese] values.” Instead of a moral code defined by Islam, Uyghurs are told to embrace twelve secular values identified by the state: prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, freedom, equality, righteousness, lawfulness, patriotism, professionalism, sincerity, and friendliness. The message is reinforced through hundreds of storefront speakers, billboards, and convenience police stations.

These values have even been put to song. Beginning in June 2017 and continuing through the fall, authorities forced all shop and restaurant owners to play the melody on a continuous loop. The “Ethnic Declaration of the Chinese People” anthem declares:

The lyrics provide Uyghurs with a new creed and blueprint for model behavior enforced by face-recognition cameras and spot checks. As part of “Eastern Civilization” and members of the multiethnic Chinese people, Uyghurs are expected to accept, internalize, and embody the twelve core values of the New China. There is no room for faith in values and norms other than those propagated by the state. This unilateral approach elicits public compliance through the institution of a police state that enforces Han conceptions of norms and extremes. This process neither builds trust nor engenders loyalty among Uyghurs—and until they have meaningful forms of self-determination and autonomy, resentment will only continue to grow.

Darren Byler is a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington. His research focuses on Uyghur dispossession, culture work, and “terror capitalism” in Ürümchi. He has published research articles in Contemporary Islam, Central Asian Survey, and the Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art and contributed to volumes on the ethnography of Islam in China, transnational Chinese cinema, and travel and representation.

Timothy Grose is an assistant professor of China Studies at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana. His research on Uyghur ethno-national identity, the “Xinjiang Class” boarding school—the topic of his forthcoming book, Negotiating Inseparability in China: The Xinjiang Class and the Dynamics of Uyghur Identity—and everyday expressions of Islam in Xinjiang has appeared in the China Journal, the Journal of Contemporary China, Asian Studies Review, ChinaFile, the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, and several edited volumes on Xinjiang.