China’s Long Economic Slowdown

China’s Long Economic Slowdown

The Chinese government has rebuffed bold consumption stimulus policy. But boosting domestic household spending is precisely what the country needs to achieve healthy growth.

This article was first drafted in late 2024, when the Chinese government pledged new rounds of stimulus measures to boost domestic consumption in 2025. As expected, the stimulus has been less substantial than anticipated. As of early April, China’s consumer price index has declined for two consecutive months, indicating persistent deflationary pressure and weak demand. Concurrently, the Trump administration has escalated its trade war, making it increasingly difficult for Chinese manufacturers to export their surplus capacity. The challenges facing the Chinese economy discussed here are only likely to intensify.

—Ho-fung Hung, April 10

The China boom has ended. The country’s annual economic growth rate has decelerated from a height of more than 14 percent in 2007 to less than 6 percent in 2023. Total indebtedness (including both internal and external debt) surpassed an alarming 365 percent of GDP as of the first quarter of 2024, according to the Institute of International Finance—much higher than comparable middle-income countries like Brazil (208 percent), Argentina (152 percent), and Indonesia (86 percent). The collapse or near collapse of real estate giants like Evergrande, which just a few years ago was the poster child for China’s economic miracle, is just one example of the country’s economic difficulties.

Over the last three decades, China has experienced multiple economic crises driven by domestic imbalances or external shocks, including overheating in 1992–93, deflation in the aftermath of the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis, and fallout from the global financial crisis of 2008. Each time, the Chinese economy turned around swiftly thanks to decisive policy adjustments (Zhu Rongji’s reforms in 1994), new openings to trade (the 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization), and aggressive financial stimulus (the 2009–10 state-driven investment spree). These past successes have led many China watchers to assume the Chinese government can repeat the magic and rejuvenate the economy once again. But China’s current economic crisis has resulted from a long and deep structural imbalance that will be much more difficult to resolve.

What Stimulus Can’t Buy

China’s slowdown, which started in the early 2010s, was aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet since the end of pandemic lockdowns, the government has been reluctant to roll out the bold stimulus that many economists inside and outside China have called for. There was a good reason for this hesitation: with increasing indebtedness and fiscal crises at multiple levels of government, any stimulus would initially worsen the public debt burden, even if it eventually succeeded in reviving growth—a big if. The structural advantages that propelled rapid growth from roughly 1980 to 2010 have been exhausted. To get back on track to healthy growth would require a profound restructuring of China’s political economy through boosting domestic household consumption.

By the fall of 2024, the economic situation had turned so dire that Xi Jinping’s government began to roll out a long-delayed stimulus package. When it was first announced in September, economic pundits and financial markets responded with jubilance, hoping the government would usher in measures to stimulate consumption. Beijing had plenty of proven policies at its disposal, including direct cash transfers to marginalized populations, like Brazil’s Bolsa Família, and tax credits to working families, like the child tax credit in the United States.

But in the end, the announced package lacked any large-scale consumption stimulus, at least for the time being. Instead, it included more of the same policies of earlier stimulus efforts: boosting bank lending, allowing distressed local governments to refinance their existing debt, and encouraging home buying through easier mortgage borrowing. Even the usually austere IMF warned that the stimulus was insufficient to prevent deflation in China.

At the end of 2024, official sources indicated that to further stimulate growth, the central government would issue 3 trillion yuan ($411 billion) worth of special sovereign bonds in 2025, but with scant details about how the raised funds would be used. In 2024, 70 percent of the proceeds from long-term special sovereign bonds issued were used to finance infrastructure construction and enhancement of state security capacity, while the remaining 30 percent was split between large-scale equipment upgrades of enterprises and subsidizing appliances and car consumption.

Structural Underconsumption

Since the late 1990s, Chinese officials and economists have cautioned that the country’s growth model relies too much on boosting production capacity and output while repressing consumption. (Most famously, Chinese premier Wen Jiabao warned in 2013 that the Chinese economy was “unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.”) This model only worked as long as China could export its way to prosperity. With the world economy turning away from free trade to protectionism, and with so many sectors—from steel to automobiles to coal—plagued by overcapacity, falling prices, and falling profits, China desperately needs to reorient its policies and resources away from encouraging the buildup of more production capacity and toward household consumption.

In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, the Chinese government had an opportunity to embrace consumption-boosting stimulus. However, its response to the crisis in 2009 and 2010 was instead a massive financial stimulus, which opened the floodgates of state bank lending to support corporations’ and local governments’ construction frenzies. Measures to stimulate household consumption were nowhere to be seen. In the end this round of stimulus left China with even more excess capacity in steel manufacturing, coal power, and housing, among other sectors.

Ten years ago, I argued in The China Boom that the difficulty in embracing a shift to stimulating household consumption, despite the availability of effective policies, was a political one. Manufacturers and local governments that depended heavily on land development and construction projects had extensive influence over policymaking, while the rural and urban laboring classes were underrepresented. Direct cash transfer programs, adopted by governments around the world partly out of electoral considerations, had few advocates within the Chinese system, even as many scholars suggested they were necessary for the long-term rebalancing of the economy. The political order was preventing the government from pursuing bold consumption stimulus policy.

From Demographic Windfall to Demographic Shortfall

China’s economy faces other structural headwinds, including significant demographic changes. For decades, the country’s production machine has been driven largely by the competitiveness of wages in its manufacturing sector. China’s huge surplus rural population provided a seemingly unlimited supply of labor, while the lack of independent unions enabled repression of wages and other labor demands. China therefore enjoyed a low-wage advantage much longer than other Asian economies. The plentiful labor supply was not only a natural phenomenon of China’s demographic structure, but also a consequence of the government’s rural policies after 1994, which disinvested from the countryside, arresting rural agricultural and industrial development. This in turn generated a continuous exodus of rural migrants to urban coastal cities in search of jobs in the export-oriented manufacturing sector. The low-wage advantage began to fade after 2010, however, as the stock of young rural workers started to become depleted.

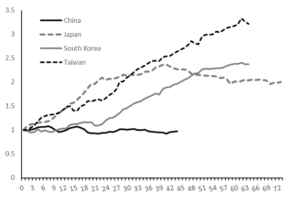

For other Asian export-oriented economies, economic development has been accompanied by a falling fertility rate and a decline in working-age population as a share of total population. This in turn tends to drive a decline in the rural population and an increase in manufacturing wages. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all underwent this transition by the 1970s and 1980s. They overcame the growth bottleneck brought by the exhaustion of rural surplus labor—known in economics as the “Lewis turning point”—and renewed growth through industrial upgrading and financial reform, which served to boost productivity. We can see this in the trend of rising total factor productivity (TFP), which combines both labor and capital productivity (Figure 1 below).

For more than a decade China has confronted the same challenge of demographic transition. However, because of the Communist Party’s draconian one-child policy, in place from 1980 to 2015, China’s demographic transition came at an earlier stage of development compared to other Asian countries. As measured by the shrinking share of working-age population and an increasing elderly dependency ratio, China’s population aged much earlier, when its per capita income had just reached the middle-income level. And in 2022, China’s population shrank for the first time since the height of the famine in 1961, during Mao’s Great Leap Forward.

Technological Upgrades?

While China’s population dividend is ending, China’s progress in industrial upgrading and productivity growth has been much slower than in other Asian exporters at comparable stages of development. Since at least 2010, the Chinese government has emphasized the importance of moving up the value chain in manufacturing and boosting exports of higher-tech products. On the surface, China has made significant progress in this regard, as reflected in its manufactured exports. But in reality, China’s upgrading has been far less satisfactory than the figures suggest. Most Chinese exporters of higher-value-added products rely heavily on imported high-tech components or foreign technology. While the resulting high-tech products are assembled in China, many of their parts are manufactured elsewhere; the iPhone, Huawei’s 5G base station, and China’s homemade C919 aircraft are cases in point.

The Chinese government has also invested massive resources to foster innovation. As a result, the number of patents registered in China rose rapidly in the last decade. However, more nuanced analysis shows that many of those patents were commercially worthless; more than 90 percent of China-registered patents are not renewed after five years. As government investigations have recently revealed, many patents are fraudulent or of low quality, churned out by research units or enterprises to show results after pocketing huge sums from research grants. The situation is so serious that the government recently initiated an anti-corruption campaign specifically targeting fake innovations.

The lack of protections for intellectual property rights likewise stands in the way of local innovation. And the IP balance of payments shows that China remains largely an IP deficit country despite pockets of innovative breakthroughs, meaning at the aggregate level, China pays much more for foreign patents and copyrights than foreign entities pay for Chinese ones. This deficit has deepened just as China’s manufactured products have moved up the value chain, further showing that many of its high-tech products rely on foreign technology.

To be sure, the tremendous government resources granted to corporations to facilitate work on selected technologies have brought significant breakthroughs. The recent success of China’s electric vehicle sector, based on the low-cost lithium battery technology that China has mastered, is a prime example. Nevertheless, this technological advance came only through wasteful expansion of EV investment that led to overcapacity and price wars. Chinese EV manufacturer BYD has managed to break into global markets, but myriad other EV makers have gone under or are on the road to oblivion. The sector’s technological gains came at the cost of inefficient, wasteful allocation of capital.

With disappointing upgrading, wasteful investment, and overcapacity, China’s high-speed growth has done little to raise productivity. TFP growth has slowed and even declined. China has mostly relied on extensive growth—increasing the mobilization of labor and capital resources—instead of intensive growth, which is driven by rising productivity. After its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the country experienced modest productivity growth driven by foreign direct investment, but this reversed after 2010. Once the population windfall was exhausted and debt-fueled fixed asset investment had reached its limit, stagnation ensued, leading to a long economic slowdown. If we measure China’s total productivity growth in comparison with other Asian economies, with the start of their industrial takeoff as year zero, its dismal performance becomes more obvious. From 1951 to 1981, Japan’s TFP grew by 115 percent. Taiwan’s and Korea’s grew by 114 and 50 percent, respectively, from 1960 to 1990. From 1980 to 2010, China’s TFP grew by only 1.7 percent, and dropped 4 percent from 2010 to 2023 according to one estimation, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Growth Index of Total Factor Productivity on Constant National Price from Year of Takeoff (Japan=1951; Taiwan/Korea=1960; China=1980)

Source: Conference Board Total Economy Database

While Japan, Taiwan, and Korea all saw their working populations proportionally decline as part of their demographic transition, their economies nevertheless continued to grow—Taiwan and Korea more than Japan—through ever-increasing labor and capital productivity. The latter was thanks to strengthened intellectual property protections and financial reforms designed to boost domestic innovation and improve the efficiency of capital allocation. This has not yet happened in China.

Demographic Drag on Consumption

In other Asian economies, governments developed public health, public education, and other social welfare institutions during boom years. Increased social security helped check the increasing propensity to save that occurs as populations age. Thus even when populations age and demographic growth slows, private consumption as a share of GDP holds up and continues to help drive the economy. The household consumption share of GDP in Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan has rarely fallen below 50 percent since their takeoff in the 1960s. This is much higher than in China, where the consumption share has never exceeded 45 percent since 2000, and has been stuck below 40 percent since 2005.

Rather than expanding social welfare, China’s market reforms went hand in hand with the dismantling of collective institutions—people’s communes in the countryside and work units in the cities—that used to provide housing, medical care, education, pensions, and other public goods, without establishing effective alternatives. The consequence is that after more than three decades of reform, Chinese households now have to rely on the market for their basic needs, and on their own savings for retirement. As a result, Chinese household consumption growth has for a long time lagged behind economic growth. This disparity is the root cause of China’s economic imbalance.

As the population ages, households with little public welfare to count on naturally become more cautious about spending. The demographic transition, therefore, further dampens consumption growth. With the failed takeoff of the consumption engine, the Chinese economy stands to become even more reliant on exports and foreign investment, which are running out of steam given the exhaustion of low-cost rural surplus labor. Combined with unreformed political and social systems, demographic transition has created an economic crisis that can only be overcome by a profound restructuring of China’s growth model.

Securitizing the Regime Over Rejuvenating Growth

Since the beginning of market reform in the 1980s China observers have assumed the party-state’s first imperative was to deliver economic growth as a way to legitimize the regime. But this assumption is not necessarily true; the real imperative of the party-state is to ensure the longevity of the regime itself.

The reforms necessary for reigniting economic dynamism in China would involve mobilizing massive fiscal resources to empower the laboring classes, shoring up an independent legal system to protect intellectual property rights, and liberalizing a financial system tightly controlled by the state, to name just a few of the needed steps. All these reforms risk undermining the party-state’s control of society and the economy. To avoid such a path, the CCP might well choose a grim alternative: to endure economic deterioration while securitizing the state with more draconian surveillance and increased revenue extraction from a slowing economy. It matters little that such tightened control would further damage the economy, so long as the state’s supreme power is secure. This is how many autocratic regimes—from North Korea and Russia to Iran and Venezuela—survive economic crises. Despite the wishful thinking of many China observers that Beijing will opt for the first path, it looks like it is digging in on the second.

Ho-fung Hung is the Henry M. and Elizabeth P. Wiesenfeld Professor in Political Economy in the department of sociology and Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. He is the author of The China Boom (2015), Clash of Empires: From “Chimerica” to the “New Cold War” (2022), and The China Question: Eight Centuries of Fantasy and Fear (forthcoming).