Can Biden Be Pushed Left?

Can Biden Be Pushed Left?

History suggests that what you see on the campaign trail, or even in a candidate’s past legislative record, is not necessarily what you get from a president once in power.

In the autumn of 1932, as the most desperate winter of the Depression approached, Franklin Delano Roosevelt campaigned for the presidency on a program of slashing federal spending by 25 percent. “I regard reduction in Federal spending as one of the most important issues of this campaign,” he declared in a speech in Pittsburgh that October. “In my opinion, it is the most direct and effective contribution that Government can make to business.” It would have taken uncanny foresight to predict that in just a few short years, FDR and his New Deal would become virtually synonymous with Keynesian deficit-spending and the creation of the nation’s first social safety net.

Roosevelt’s attachment to fiscal austerity was not mere campaign rhetoric. Six days after his inauguration, he sent the Economy Act to Capitol Hill, mandating $400 million in cuts to veterans’ pension benefits (the equivalent of $10.3 billion today) and another $100 million in reductions to federal employee pay. By March 15, it was law. “Under the leadership of Franklin Roosevelt,” the historian William Leuchtenburg has written, “the budget balancers won a victory for orthodox finance that had not been possible under Hoover.”

At the time of his election, Roosevelt was not an ideologically consistent politician. Determined to try anything to jump-start the moribund economy, he surrounded himself with a diverse group of advisers holding often contradictory views. In his first hundred days, the fiscal austerity of the Economy Act was incongruously coupled with expensive state-sponsored initiatives like the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the National Industrial Recovery Act.

In popular imagination, the New Deal has come to be identified with far-reaching reforms that empowered workers and created the infrastructure for an enduring social safety net. But these achievements were only possible because vibrant mass movements reshaped the political landscape and pushed Roosevelt to the left. The Wagner Act, which required corporations to engage in collective bargaining with workers for the first time in U.S. history, offers a case in point. Its passage made possible the birth of the modern industrial labor movement, and “when passed,” as one legal scholar has written, it “was perhaps the most radical piece of legislation ever enacted by the United States Congress.” But Roosevelt had little to do with its enactment. The president “never lifted a finger” for the bill, his Labor Secretary Frances Perkins would recall later. She continued: “Certainly, I never lifted a finger. . . . I, myself, had very little sympathy with the bill.” In 1934, the year before the bill passed, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike and took to the streets of cities across the country. This action generated irresistible momentum for the new collective bargaining law. At the same time, unemployed workers rallied for relief; seniors demanded a measure of economic security in retirement; and populist Louisiana Senator Huey Long spawned a network of 27,000 “Share Our Wealth” clubs that would loom as an electoral threat to FDR in 1936. These powerful social movements transformed the 1932 apostle of austerity into the president who declared at a 1936 campaign rally that the forces of “organized money . . . are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

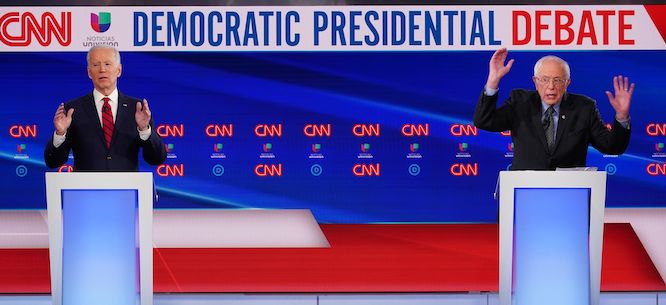

With Election Day just weeks away, it is worth recalling this New Deal dynamic of mass movements and social reform. For many of us, the 2020 Democratic primaries left a bitter taste of disappointment and resentment. The rapid consolidation of the Democratic establishment—and of the primary electorate—in support of Joe Biden in the days before Super Tuesday thwarted the left’s hopes of nominating a transformational standard bearer. And Biden, of course, has many shortcomings: a centrist legislative record, sometimes head-scratching rhetorical ineptitude, and an outdated penchant for bipartisan compromise. Yet history suggests that what you see on the campaign trail, or even in a candidate’s past legislative record, is not necessarily what you get from a president once in power.

Transformational leadership is determined not only by the character, or even by the ideology of a particular leader, but by a complex interplay of social forces and historical circumstance. Perhaps most importantly, mass popular mobilizations can shift the frame of debate and push leaders beyond where anyone expected them to go. History demonstrates that this dynamic can produce surprising breakthroughs, even when activists may least expect them.

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was the compromise candidate of a political party whose stance on slavery leading abolitionists dismissed as an unacceptable compromise. The Republican Party, founded in 1854, accepted the prevailing constitutional interpretation that the federal government lacked the authority to outlaw slavery in the states where it existed; instead Republicans advocated “free soil,” preventing slavery’s spread into the new western territories, and for disassociating the federal government from direct support of slavery. This political expedience outraged abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, who fumed in 1855: “Free soilism is lame, halt and blind, while it battles against the spread of slavery, and admits its right to exist anywhere.”

The campaign dynamics of 1860 drew Lincoln in an even more cautious direction. In 1856, the anti-immigrant, “Know-Nothing” candidacy of former president Millard Fillmore had drained votes from Republican nominee John Frémont, leading to a decisive victory for the Democratic “slaveocracy.” Lincoln tried to avoid the same fate by courting nativist voters in Indiana, Illinois, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, that era’s battleground states. His campaign toned down Republican positions on denationalization of slavery, and highlighted other issues, like the tariff, to attract swing voters.

The radicals of 1860 were appalled. The Republican Party, declared William Lloyd Garrison, “may not be in all respects as bad as another party, but is so bad that I cannot touch it, and will not give it any countenance whatsoever.” Edmund Quincy, anticipating the arguments of subsequent generations of radicals, claimed there was no meaningful difference between the two major parties. The election was destined to produce, he wrote, “a new administration pledged to the support of slavery in our Southern States, and this equally, whether success be to the Democrats or the Republicans.”

After Lincoln’s victory, abolitionist disillusionment with the new president continued to mount. Throughout much of 1861 and 1862, the president continued to insist that preservation of the union was the sole objective of the war, refused to recruit Black troops into the Union Army, and sought to placate slave-holding border states with proposals for compensated emancipation and the overseas colonization of freed slaves. In June 1862, Wendell Phillips, perhaps the foremost white abolitionist orator and one of the most radical, erupted in anger in a letter to his friend Charles Sumner, the Radical Republican senator from Massachusetts: “Lincoln is doing twice as much today to break this Union as Davis is. We are paying thousands of lives and millions of dollars as penalty for having a timid and ignorant President, all the more injurious because honest.” At a meeting of the New England Anti-Slavery Society in late May, Stephen Foster took his critique of the fledgling two-party system to the furthest extreme. “Abraham Lincoln is as truly a slaveholder as Jefferson Davis,” he said. “He cannot even contemplate emancipation without colonization.”

But Lincoln was not the same as Jefferson Davis. He hated slavery, even if he was acutely attuned to northern political opinion and often calibrated his positions to sustain majority support for the war. And just like in the 1930s, grassroots agitation, legislative radicalization, and historical circumstance combined to bring Lincoln to a turning point in the struggle against slavery. Early in 1862, Frederick Douglass concluded a speaking tour in which he traveled thousands of miles and gave hundreds of speeches demanding “abolition war” and the recruitment of Black troops into the Union war effort. A mass movement of runaway slaves—the “contrabands of war”—presented themselves to advancing Union armies, seeking refuge from bondage and offering to join the war effort. Finally, after the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln announced plans for the Emancipation Proclamation, at last making abolition the primary objective of war. Black troops would be recruited to the cause, albeit at discriminatory rates of pay. As Karl Marx observed in an article in the New York Tribune, “Up until now, we have witnessed only the first act of the Civil War—the constitutional waging of war. The second act, the revolutionary waging of war, is at hand.”

Mass movements would shape presidential leadership a third time in the modern civil rights era. Lyndon Johnson was a dyed-in-the-wool New Deal Democrat who grew up dirt poor in the Hill Country of Texas in the first decades of the twentieth century. His biographer, Robert Caro, writes that Johnson’s own poverty and humiliation left him deeply empathetic toward impoverished people of color, in particular the Mexican-American children he taught during a brief stint as a schoolteacher on the eve of the Great Depression. But Southern populist enthusiasm for New Deal programs like rural electrification, agricultural price supports, and public power was always limited by the imperative of preserving the region’s racial and economic status quo. One-party rule in the South helped to ensure segregationist dominance of Congressional chairmanships awarded according to strict rules of seniority; this “southern cage,” as Ira Katznelson has called it, guaranteed that much of the New Deal disproportionately excluded Black workers.

Institutional racism was complemented by unconcealed racist prejudice. Robert Parker, Johnson’s occasional chauffeur and, during the 1960s, the maître d’ of the Senate dining room, recalled in his autobiography that Johnson never called him by his given name. “He especially liked to call me nigger in front of southerners and racists like [Georgia Senator] Richard Russell,” wrote Parker. “It was . . . LBJ’s way of being one of the boys.” First elected to Congress in 1937, Johnson believed for two decades that his path to power lay in an alliance with the Southern segregationist bloc. He voted against legislation establishing a Fair Employment Practices Commission and a bill that would have outlawed poll taxes. He repeatedly helped Southern senators filibuster civil rights legislation proposed by northern Democrats.

But social movements would force Johnson to revise his political calculus. Johnson rose to Senate Majority Leader in 1955, and soon began plotting a run for the presidency. Doing so meant navigating a far different political landscape than the one-party Southern oligarchy, which had dictated his formative political decisions. By the mid-1950s, the rise of the CIO, which was committed to cross-racial industrial organization, coupled with the emergence of the civil rights movement of the 1940s, exemplified by A. Philip Randolph’s wartime campaign for fair employment within federal agencies and war-related production, had shifted the racial politics of the northern Democratic Party. The second wave of the Great Migration created significant Black voting blocs in many northern cities. And in 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott inaugurated the modern civil rights movement, in which Black-led, non-violent mass movements challenged nearly 100 years of Jim Crow. Johnson recognized that a Southern Democrat with an unbroken record of hostility to civil rights could not be a credible national candidate for president. And so in 1957, drawing on all of his legendary skills as a legislative tactician, the “Master of the Senate” orchestrated the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, a bill with limited practical impact but great symbolic significance as the first piece of civil rights legislation passed since Reconstruction.

This dynamic only intensified after Johnson’s ascension to the presidency following John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963. An escalating series of sit-ins, boycotts, and demonstrations across the South had forced the “American dilemma” to the forefront of national consciousness. Jim Crow had become an unsustainable Cold War embarrassment. With his eye firmly set on the 1964 election, Johnson moved quickly after Kennedy’s death to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in education, employment, and public accommodations, defeating a sixty-day filibuster. And once Johnson was re-elected, the pace of reform accelerated. The ongoing Black Freedom struggle, coupled with an outbreak of student protests like the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley, California, created a movement moment.

The climactic confrontation on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in March 1965 prompted Johnson’s remarkable speech to a joint session of Congress eight days later, endorsing the passage of a sweeping voting rights legislation. When the president, for twenty years one of the nation’s staunchest segregationists, concluded his speech by drawling “We Shall Overcome,” Martin Luther King Jr., watching on the television in Selma, cried. And voting rights was just the beginning. The movements had set the stage for one of the most remarkable flurries of progressive legislative activity in the nation’s history: Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, Food Stamps, Model Cities, the Community Action Program, expansion of minimum wage and Social Security coverage, the Fair Housing Act, and numerous environmental protection laws were all established or consolidated. In an historical instant, Johnson’s Vietnam debacle would send millions of Americans into the streets to oppose his policies and vilify him personally. But for that brief period in the mid-1960s when presidential leadership rode the wave of mass progressive movements, enormous accomplishments were made.

Despite the unpredictability of the future and the historical specificity of past eras of progressive advance, the experiences of the 1860s, the 1930s, and the 1960s offer several lessons for radical activists as November 3 approaches. First, the frustrating limitations of the U.S. two-party system are nothing new. We tend to think of “lesserevilism” as a Hobson’s choice forced on progressives and labor activists as Democrats steadily abandoned New Deal politics and moved to the pro-corporate center in the years after Ronald Reagan’s ascendance. But the problem of choosing between the lesser of two evils is as old as the two-party system. Even after Lincoln’s emancipationist turn in 1863, many abolitionists remained deeply frustrated by his failure to accord Black soldiers equal treatment with their white counterparts and his reluctance to support voting rights for the freed slaves. Wendell Phillips, for example, declared he would “cut off both hands before doing anything to aid Abraham Lincoln’s election.” But most abolitionists ultimately came to believe that a victory for Democrat George McClellan would jeopardize the sacrifices and gains of the previous four years and possibly result in a peace agreement which would leave the slave system intact. Anna Dickinson, a rising young star of the abolitionist lecture circuit, articulated this view in September 1864: “This is no personal contest. I shall not work for Abraham Lincoln; I shall work for the salvation of my country’s life . . . for the defeat of this disloyal peace party, that will bring ruin and death if it comes into power.” These words echo across the centuries, at a moment when our “country’s life,” and democracy itself, appear to hang in the balance.

The second lesson that we can draw from these historical precedents is that the rhetoric, the platforms, and even the past records of candidates are far less important than we often think. Radicals initially had scant reason to believe that Roosevelt, Lincoln, or Johnson might eventually produce some of American history’s most progressive accomplishments. But a combination of crisis and mass movements transformed these presidents, pushing them to enact far-reaching policies that were unimaginable at the beginning of their tenures. This is not to argue that Joe Biden is an FDR, LBJ, or Lincoln in waiting. But obsessing over his limitations misses the point. We can afford no illusions about the ground rules of the U.S. two-party system. Electing Biden is the precondition for progressive advance; Trump’s re-election would be a foreclosure of hope. We must therefore stay focused on two critical tasks: ending the regime of Donald Trump and building the mass movements that can make a Joe Biden presidency a transformational moment.

Finally, we should recognize that across U.S. history, moments of progressive advance have been infrequent and relatively short-lived—1862 to 1875, 1933 to 1938, 1964 to 1968. We may be on the eve of another such moment, when possibilities of radical change open up in ways that were only recently inconceivable. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders fell short in the primaries, but their ideas captured the imagination of voters, particularly among youth, and shifted the terms of debate. For or against, all the Democratic candidates had to respond to the substantive challenges posed by Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, a new wealth tax, universal child care, eliminating student debt, and a $15 an hour minimum wage. Just as “the labor question” shaped both elite and popular debate over how workers should be treated and production organized in the decades prior to the New Deal, the last decade has seen a steadily growing awareness of the need to address pressing issues of racial injustice and economic inequity.

Then the pandemic hit, casting an unsparing light on the catastrophic inability of our society to meet the nation’s needs—and the profound racial and class inequities that determined who suffered the greatest impact of the crisis. It is a poignant historical irony that at the very moment when the candidacy of the candidate who did more to advance a social democratic program in U.S. politics than perhaps any politician in U.S. history was collapsing, an unprecedented social crisis erupted that made plain the need for an invigorated American social democracy informed by a deep commitment to racial justice: one with truly universal health care, a robust public health system, strengthened workers’ rights, massive investments in reversing climate change, universal child care, expanded paid family leave, and a stronger safety net for the unemployed. But Bernie’s ideas have outlived his campaign; coupled with the deeply disruptive impact of the pandemic, they have pushed candidate Biden further to the left than any of us might have thought possible, on issues of climate, racial justice, and an expanded social safety net. And the magnificent impact of the Black Lives Matter upsurge over the last several months demonstrates the remarkable power of social movements to reshape public opinion and policy discourse in what seems like an instant. These conditions have set the table for an historic era of reform if we do our work over the next few months.

Let Frederick Douglass provide the last word. Despite his contempt for “free soilism,” Douglass understood that the Republican Party nevertheless represented a breakthrough in American politics—a major national party which, although not abolitionist, was contesting for power on anti-slavery principles. As the 1856 election approached, Douglass determined to cast his vote for what was clearly the “lesser of two evils.” His explanation of that decision resonates with the choices we face today. “Anti-slavery consistency itself requires of the anti-slavery voter that disposition of his vote . . . which, in all the circumstances . . . tend[s] most to the triumph of Free Principles,” Douglass argued. “Right anti-slavery action is that which deals the severest deadliest blow upon slavery that can be given at that particular time.”

Our first imperative in 2020 is a massive repudiation of Donald Trump. There is only one way to do that. A vote for Joe Biden will deal the deadliest blow against Trumpism, authoritarianism, racism, and reaction. Our second obligation is to organize social movements that will force President Biden and a Democratic Congress to take long overdue steps toward fundamental social and economic reform. We must be sharply focused on both tasks over the coming weeks and months.

Bob Master has worked in the labor movement for forty-three years. He currently serves as Assistant to the Vice President for Political and Mobilization Activities in District One of the Communications Workers of America. He was a co-founder of the New York Working Families Party and is a member of the WFP National Executive Committee.