A Popular Front, If You Can Keep It

A Popular Front, If You Can Keep It

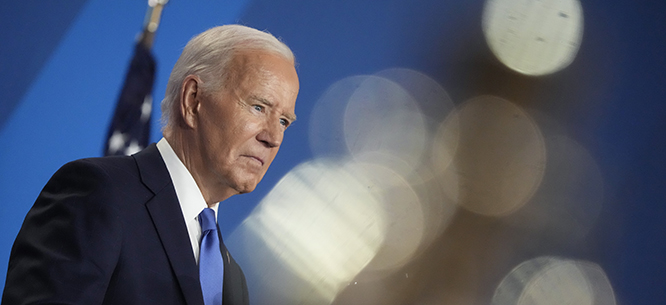

Biden claims he is remaining in the race because the threat of Trump is too great. That’s the exact reason he should consider retiring.

A popular front is called into being for one purpose: to defeat the threat of an extremist, far-right political movement. Political factions from left to center put aside their differences and unify, temporarily, around whatever common platform can be found. Since 2020, the Democratic Party has operated as much like a popular front as one can in a presidential system. In 2020, that coalition barely constituted an electoral majority, but it did triumph. But the coalition has not adapted to the new circumstances that 2024 presents and is at risk of catastrophic failure. A change is needed, quickly, and it must come from the top.

The Republican Party is currently confident of victory. Donald Trump has solidified his control over the party, expanded the range of voters who view him positively, and survived an assassination attempt. In J.D. Vance, he has chosen a vice-presidential candidate who can solidify his impulses into ideology and serve as a conduit to the most reactionary sectors of Silicon Valley capital. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 is full of chilling plans to put the power of the state behind the far right’s culture war. Delegates at the Republican National Convention held aloft signs calling for “Mass Deportation Now!” Call it what you will, but there is a word in the political lexicon for patriotic nationalism that deploys state power to punish internal enemies.

President Joe Biden’s team was counting on his debate performance on June 27 to remind people of Trump’s malicious character and shake up a race that had been something close to a toss-up. Instead, the night revealed Biden’s own mental and physical frailties. National and swing-state polling has only worsened since then. Biden has delivered uneven performances in the days since. But he has also developed a disturbingly familiar line of reasoning: that only he can fix it.

Being able to mobilize people around a common project for the future is the fundamental task of a leader in democratic politics. Even on his better days, Biden is struggling to do this. His administration has a record that is in many areas worth defending. In the Democratic Popular Front of 2020–2024, the left was very much the junior partner. Its leverage was limited, and it was far from being able to accomplish all of its goals. Nevertheless, the Biden administration has been friendlier to labor, better for the climate, and bolder on regulations than any president in at least fifty years. The unprecedently strong labor market has helped raise wages and reduce inequality.

But Biden has not presented an agenda for a second term around which it is easy to mobilize. Reestablishing legal abortion in places where it has been stripped away is an issue where the public should be on his side, but Biden is uncomfortable with it. Asked to justify why he needs a second term, he mumbles about being the only person who can hold NATO together—while other heads of state take steps to protect him.

The chorus of voices that has risen to call for Biden to yield his place on the ticket has not been a particularly ideological one. Indeed, both Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (who in 2020 observed that in “any other country” she and Biden would not be in the same party) and Bernie Sanders (who subsequently acknowledged that Biden has trouble completing sentences) have defended the president and seem to view the conversation about replacing him as counterproductive and divisive.

It may be that Sanders and AOC are right. Though polling suggests otherwise, perhaps no one can do better than Biden. Sanders and AOC have tried to leverage their ongoing support to provide him with an economic agenda for his second term. They may fear that they would lose influence with another candidate in the lead. The circumstances that produced the Democratic Popular Front—the open primary that allowed different factions to measure their relative strength—will not be repeated. And on one level, Ocasio-Cortez’s reasoning is ironclad: she is absolutely right to argue that whatever disagreements she has with Biden, she would rather be in the organizing environment of a Biden administration than a Trump one. But none of this will matter if there is no second term.

Instead of a clear vision for a second term, Biden has made the threat of Trump to democratic institutions the centerpiece of the campaign’s message. Politically, this approach (along with the defense of abortion rights on ballot initiatives) helped support Democratic turnout in the 2022 midterms. Dislike of Trump is deep, and it will put a floor under Biden’s performance. Many millions of people will reason that an infirm Biden is preferable to a malicious Trump and cast their votes accordingly in November.

But it also appears that Biden thinks that this argument against Trump is self-executing. He seems not to have recognized that even dictatorships command a degree of popular support. (The most popular head of state in the hemisphere, and possibly the world, is El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, who swept away weak democratic institutions as part of his anti-crime agenda. He is now greeted enthusiastically at CPAC.) To simply talk of the defense of democracy is not enough. It is not that the defense of democracy is a “post-material” demand—autocracies tend to reward loyalty rather than competence, eventually leading to disaster. But the connection needs to be made for people that their well-being is at risk in multiple ways by a second Trump term, in both material and moral domains.

Authoritarianism can be popular, and the more popular it is, the greater its ability to remake society in its image. This is why the threat of Trump in 2024 is so serious. Recovery would probably be a generational project, not a matter of an election or two. The anti-Trump bloc was larger than the pro-Trump bloc in 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022. If it is not larger in 2024, it will be because of the political malpractice of a campaign that is convinced that its superiority is self-evident and thus dismisses concerns about the candidate leading it. Such a campaign already lost to Trump in 2016.

No strategy available to the Democrats is without considerable risks at this point. Many unpredictable things happen in politics all the time, and Biden still might win. But keeping him represents a “low ceiling, high floor” strategy, in which the low ceiling looks like a loss. Under the circumstances, risking a “high ceiling, low floor” candidate may be the only reasonable choice. The Democratic Party has little time left to show that it understands how to be a vehicle for popular sentiment. The popular front is on a knife’s edge. I worry about what its failure will mean and am deeply frustrated that it has been so poorly tended.

Ocasio-Cortez responded recently to an anonymous senior Democrat who was quoted as saying “We’ve all resigned ourselves to a second Trump presidency” with anger, replying: “This kind of leadership is functionally useless to the American people. Retire.” But to many who are not ready to give up on stopping such an outcome, it seems that it is Biden who is resigned to a second Trump presidency. What then should he do?

Patrick Iber teaches history at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.