Weathering the Ups and Downs of Social Movements

Weathering the Ups and Downs of Social Movements

How do we know when movements have died—and when are they primed to revive?

Cross-posted from Waging Nonviolence.

Those who get involved in social movements share a common experience: sometimes, when an issue captures the public eye or an unexpected event triggers a wave of mass protest, there can be periods of intense activity, when new members rush to join the cause and movement energy swells. But these extraordinary times are often followed by long, fallow stretches when activists’ numbers dwindle and advocates struggle to draw any attention at all.

During these lulls, those who have tasted the euphoria of a peak moment feel discouraged and pessimistic. The ups and downs of social movements can be hard to take.

Certainly, activists fighting around issues of inequality and economic justice have seen this pattern in the wake of Occupy Wall Street. Many working to combat climate change have encountered their own periods of dejection after large protests in recent years. And even members of movements that have been very successful—such as the immigrant students who compelled the Obama administration to implement a de facto version of the Dream Act—have gone through periods of deflation despite making great advances. Further back in history, a sense of failure and frustration could be seen among civil rights activists following the landmark 1964 Freedom Summer campaign.

After intensive uprisings have cooled, many participants simply give up and move on to other pursuits. Even those committed to ongoing activism wonder how they can keep more people involved over the long haul.

Unfortunately, the fluctuating cycles of popular movements cannot be avoided. Unlike community organizing, which focuses on the slow and steady building of organizational structures, a boom-and-bust pattern is inherent in mass protest movements. Wide-scale uprisings can make a major impact on public consciousness, but they can never be sustained for long. The fact that they fade from view does not mean they lack value—the civil rights movement, for one, scored many of its biggest wins as a result of mass mobilization and the innovative use of nonviolent direct action. But it does present a challenge: Without an understanding of movement cycles, it is difficult to combat despondency.

So how, then, do we know when movements have died—and when are they primed to revive? And how do activists translate periods of peak activity into substantive and enduring social change?

For Bill Moyer, a trainer and strategist who experienced first hand some of the landmark movement cycles of the 1960s and ’70s, grappling with these questions became a life’s work. Moyer’s legacy is an eight-stage model for how movements can overcome despair and marginality to change society—a framework known as the Movement Action Plan, or MAP. Nearly three decades after it was first developed, the MAP continues to offer insights into problems that, while new to fresh generations of activists, in fact have a long lineage.

The Moyer map

Moyer was born in 1933 and grew up as the son of a TV repairman in northeast Philadelphia. As a child, he aspired to one day become a Presbyterian missionary in Africa. But a trouble-making spirit would ultimately get in the way. As he told it, “In March 1959 I was voted out of the Presbyterian Church because I invited a Catholic and a Jew to talk to the youth group.”

The expulsion led him into the arms of the Quakers. At the time, Moyer was just three years out of Penn State, working as a management systems engineer and searching for more “meaning.” Through Philadelphia’s active Quaker meetinghouse, Moyer came in contact with a vibrant circle of socially engaged peers, and an elder couple tutored him in theories of nonviolence. These encounters forever altered his life. “I had no idea that it was the start of ‘the sixties,’” Moyer later wrote, “and never suspected that I was beginning my new profession as a full-time activist.”

Without models that looked at the long arc of protest movements, Moyer contended, activists became stuck in their thinking, repeating past tactics and failing to strategize for how to effectively move their campaigns forward.

In the 1960s, Moyer would take a job with the American Friends Service Committee in Chicago, helping to convince Martin Luther King to launch an open housing campaign in the city. Moyer then worked on King’s last drive, the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C. In the decade that followed, he spent his energies protesting the Vietnam War, supporting American Indian Movement activists at Wounded Knee, and promoting the newly emerging movement against nuclear power.

As he increasingly began training other activists, Moyer saw a gap. “How-to-do-it models and manuals provide step-by-step guidelines for most human activity,” he wrote in 1987, “from baking a cake and playing tennis to having a relationship and winning a war.” Within the world of activism, however, such material was harder to come by.

Saul Alinsky and his followers had created training manuals for their specific brand of community organizing. Likewise, materials drawing from Gandhi and King were available for instructing people in how to create individual nonviolent confrontations. But Moyer believed that there was a lack of models that looked at the long arc of protest movements, materials that accounted for the highs and lows experienced by participants. The result, he contended, was that activists became stuck in their thinking, always repeating the past tactics and failing to strategize for how to effectively move their campaigns forward.

Moyer’s MAP aimed to address this need. It was initially printed in 1986 in the movement journal Dandelion, with twelve-thousand newsprint copies distributed through grassroots channels. Subsequently, it became an underground hit. The plan would continue to be circulated by hand, translated into other languages, and shared at trainings for well over a decade, before taking its final form in the 2002 book Doing Democracy, published shortly before Moyer’s death.

“Every good movement”

Of course, creating social change is a lot trickier than baking a cake. And Moyer was not the only person to propose that movements progress in stages.

Within the academic field of social movement theory, which experienced significant growth in the 1970s and ’80s, scholars were increasingly appreciating how social change happens through what sociologist Sidney Tarrow calls “cycles of contention.” Drawing on the work of theorists including Herbert Blumer and Charles Tilly, the standard academic account holds that movements pass through four stages: emergence, coalescence, bureaucratization, and decline. The last stage is not necessarily negative: movements sometimes are defeated or repressed, but other times they fade away because they have won their key demands.

Outside of academia, a variety of activists have offered thoughts of their own. In the March 9, 1921 edition of Young India, Mohandas Gandhi wrote, “Every good movement passes through five stages: indifference, ridicule, abuse, repression, and respect.” Because Gandhi’s take highlights the likelihood that resistance will be met with a crackdown by authorities, the prospect of progressing through his stages seems less inviting than riding out the academics’ model. But Gandhi believed that dissidents are strengthened by the trials they endure. “Every movement that survives repression, mild or severe, invariably commands respect,” he contended, “which is another name for success.”

In recent years British author and activist Tim Gee has gone so far to propose a four-stage model based on a popular maxim that mirrors Gandhi’s sentiment (and is often misattributed to him): “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

All of these different models have some value, but they also present problems. One problem, which Gee notes, is that various proposals for sequential stages for movements carry a sense of “implied inevitability.” The academic theories, in particular, suggest a sort of linear progression that does not reflect the experience of those living through boom-and-bust movement cycles. As removed instruments of analysis, they can leave real-world participants feeling cold. As Moyer puts it, “While there is much useful information in social movement theories, most do not help us under the ebb and flow of living, breathing social movements as they grow and change over time.”

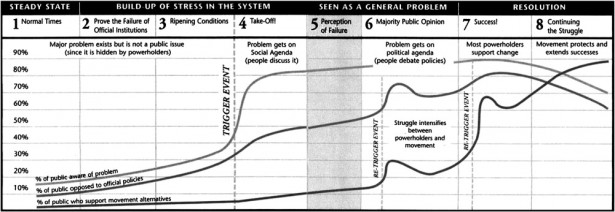

Moyer’s MAP model is a different animal. It, too, proposes a progression through which successful movements pass: over the course of his eight stages, activists raise initial awareness of a grievance, then become more organized in their efforts, engage in confrontation, and finally work to consolidate their gains. However, Moyer is much more attuned to the psychology of those who must struggle to push a cause forward. The MAP captures of the exhilaration of times when—following a dramatic “trigger event”—protests explode and “overnight, a previously unrecognized social problem becomes a social issue that everyone is talking about.” (The Occupy encampments stand out as a prominent recent trigger, just as the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle fit the bill for the global justice movement.) And the model grapples in detail with the often-challenging aftermath of such peak moments.

Rooted in hard-won experience, Moyer’s work is attentive to the different roles and personalities that can help or hinder an effort at any given stage in its development, and it is careful to warn of the common pitfalls that keep some movements from ever realizing their goals. These factors helped earn the MAP its cult popularity. Moyer was proud when trainers using his materials reported that participants would nearly gasp in recognition when his model explained patterns which they had thought were unique to their own experience. Moyer called these “Aha!” moments, and his goal was to create as many of them as possible.

The perception of failure

For those encountering the MAP model for the first time, the biggest “Aha” usually comes with Moyer’s stage five. The previous stage—stage four—is when protest movements take off, holding attention-grabbing demonstrations and experiencing rapid growth. But what comes next is not a smooth stroll to success. Instead, according to Moyer, the flurry of activity is followed by “Perception of Failure.”

With this stage, Moyer highlights a paradox: activists commonly feel let down after a spike in activity subsides. Yet, it is just at this moment that they may be poised to reap significant gains. Moyer writes, “After a year or two, the high hopes of instant victory in the movement take-off stage inevitably turn into despair as some activists begin to believe that their movement is failing. It has not achieved its goals and, in their eyes, it has not had any ‘real’ victories.”

At this point many people “burn out or drop out because of the exhaustion caused by overwork and long meetings.” Moreover, the mainstream media reinforces an air of negativity by reporting that, since protests have dropped off, the movement is dead and has accomplished nothing. All of this, Moyer writes, combines to create “a self-fulfilling prophecy that prevents or limits [movement] success.”

By identifying the perception of failure as a normal part of social movement cycles, Moyer hoped to blunt the negative force of this stage. He argued that activists who look to history will see that they are not alone in experiencing letdown. And they will also notice that past movements that were able to overcome despondency ended up seeing many of their once-distant demands realized. The key is to step back and prepare for the next stage—in which activists benefit from the increase of public awareness created by their past protests, and in which their proposals for alternative solutions are more likely to find receptive audiences.

Because feelings of failure within movements are so rarely acknowledged in other sources—far less considered thoughtfully—stage five invariably becomes a focal point when Moyer’s work is discussed. Waging Nonviolence editor Nathan Schneider applied the “perception of failure” in analyzing the Occupy movement on its second anniversary for The Nation. And none other than far-right guru and ex-Fox News titan Glenn Beck considered Moyer’s stage five in some detail in contemplating the future prospects of the Tea Party.

But, we might ask, are perceptions of failure necessarily irrational and misguided?

Clearly, there is a danger here. While everyone likes to be told that they are winning, blasé reassurances are no substitute for real analysis. It is possible to misinterpret Moyer’s model as a guarantee that, if you feel that your movement is faltering, you simply need to wait a little longer and things will work out. This is a comforting idea, and also a false one. The fate of some movements, Moyer acknowledges on the first page of Doing Democracy, is simply to fail miserably. Yours could be one of them.

The question, then, is: how does one determine when pessimism is misplaced—and how do you gauge genuine progress?

Hearts and minds

The answer is at once straightforward and counter-intuitive: movements succeed when they win over ever-greater levels of public support for their cause. This is a point that Moyers repeats constantly and consistently. “Social movements involve a long-term struggle between the movement and the powerholders for the hearts, minds, and support of the majority of the population,” he argues. Therefore, the job of activists is to “alert, educate, and win over an ever-increasing majority of the public.” Without a preponderance of public sympathy, a popular movement cannot prevail. “Because it is the people who ultimately hold the power,” Moyers concludes, “they will either preserve the status quo or create change.”

These proposals sound reasonable—perhaps even obvious—on their face. But in fact they present a serious challenge to the way in which most people think about political life. In conventional politics, the focus is not on winning over the majority of the public or transforming the climate of debate on an issue. Rather, negotiations take place in the realms of the possible and the expedient. Interest groups spend the great bulk of their energy pressuring power-holding elites to grant favors or make concessions. Success is measured by their ability to leverage power in order to secure incremental gains on the issues they care about. Social change, in this paradigm, comes about through the slow accumulation of these calculated, instrumental victories.

Even as they slowly accumulate popular sympathy, movements may lack any real traction in the halls of power. But once public opinion tips, the floodgates of change can open.

Moyer’s theory of change, based on the idea of winning majority support, rests on a different set of suppositions. In the MAP model, long stretches of time can pass where little seems to change. Even as they slowly accumulate popular sympathy, movements may lack any real traction in the halls of power. But once public opinion tips, the floodgates of change can open.

“Over the years… the weight of massive public opposition, along with the defection of many elites, takes its toll,” Moyer explains. Movement activists may have been told for as long as they could remember that their demands were naïve and politically impractical. But once majority support for their position is firmly established, this starts to change, sometimes abruptly. The limits of the possible can be redefined—as they were with civil rights in the 1960s, or with the call to phase out nuclear power in 1980s, or with gay marriage in recent years.

“The long-term impact of social movements,” Moyer contends in a sentence that would be heretical in conventional political circles, “is more important than their immediate material success.”

The idea of winning over majority public support creates a metric by which activists can judge where they stand in the MAP model—and this sets Moyer’s framework apart from other, more amorphous accounts of movement cycles. In the MAP’s early stages, during the initial ripening of conditions around an issue, less than 30 percent of the population might agree with a movement’s insistence that the status quo must change. As activists ramp up protest, greater segments of the public become aware of the problem at hand, and successful movements push levels of sympathy toward the 50 percent mark. Only after they pass this threshold does the endgame of a movement begin. At that point, change agents can shift their focus from demonstrating that a problem exists to advocating for alternatives—and they can start seeing these alternatives adopted in mainstream politics.

And then you win

A focus on “hearts and minds” provides the key to unraveling the mystery of stage five. When advocates for social change recognize that their core objective is winning over the public, they are equipped to judge whether or not pessimism about their progress is legitimate.

Perceptions of failure are warranted when movements alienate potential supporters. When periods of peak protest activity fizzle, there is a danger that some activists—a group Moyer calls the “negative rebels”—will resort to insular vanguardism. Focusing solely on building a radical core rather than on persuading the outside world, these actors advocate for increasing dramatic tactics that appeal to disgruntled activists’ militant sensibilities, but that hold little appeal for observers who are not already among the converted. When this happens, a movement becomes more and more marginal, and fears of irrelevance are not misplaced.

On the other hand, movements that are building popular support need not worry if their initial moment in the spotlight passes and the fickle news media turns its attention elsewhere. Although they may miss the enthusiasm and energy of the earlier period, they should not accept the notion that they have become irrelevant. As long as a movement has gained a larger share of public sympathy as a result of its efforts, its activists are well positioned to push for greater change. This push will typically involve continued public education, advocacy for movement solutions, and readiness to ignite fresh waves of protest when the opportunities arise.

Moyer tells the story of when he first presented the MAP model: in February 1978, he was set to give a presentation at a strategy conference to forty-five organizers from the Clamshell Alliance. This anti-nuclear group had conducted a landmark series of direct action protests against the Seabrook power plant in New England. At its peak, the previous spring, the alliance carried out an occupation of Seabrook in which 1,414 people were arrested and spent twelve days in jail. As Moyer writes, “During those two weeks, nuclear energy became a worldwide public issue as the mass media spotlight focused on the activists locked in armories throughout New Hampshire.”

In the wake of the Clamshell actions, hundreds of new grassroots groups formed around the country. The Seabrook protest would inspire further occupations in places such as the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant in California. Moreover, the organization’s methods—its affinity groups, spokes councils, consensus process, and focus on militant, nonviolent blockades—would ultimately become an influential model for direct action in the United States.

Because of all they had accomplished, Moyer expected that the group at the conference would be upbeat and celebratory. Instead, he encountered something quite different. “I was shocked when the Clamshell activists arrived with heads bowed, dispirited and depressed, saying their efforts had been in vain,” Moyer writes. Because protests had died down and construction on the specific plant they had targeted still continued, they felt defeated.

In his presentation—a sketchy version of what would become his eight stages of social movements—Moyer scrambled to demonstrate how the activists had made considerable gains. By galvanizing national opposition to the industry, the movement already reversed the near-universal acceptance of nuclear power that prevailed during the 1960s and early ’70s. Activists were well on there way to establishing majority support for their position—and seeing tangible changes as a result.

Moyer believes that the framework he presented helped many of the activists to better understand their predicament and plan for future stages of activity. Whether or not this is the case, anti-nuclear campaigns ultimately achieved a resounding victory. By making the safety, cost, and ecological impact of nuclear power into concerns shared by a majority of Americans, they created a situation in which orders for new nuclear power plants ceased, the government was forced to abandon its goal of having 1,000 facilities in operation by the end of the millennium, and the number of working plants was set on a path of steady decline—a path on which it continues to this day.

Among the majority

Social movement activists are notoriously poor at celebrating their victories. Stage five is not the only point in Moyer’s model when they are often inclined toward despair. Ironically, near the end of MAP’s eight stages, when movements begin to see concrete wins, it is again common to see participants experience depression. At this point, with a firm majority of the population in support of an issue, opportunists flourish. Mainstream politicians, centrist organizations, former critics, and once-recalcitrant power brokers all scramble to take credit for gains that have been achieved. Notwithstanding years of stonewalling, silence, and timidity, these people insist they, too, are repulsed by segregation; that they are truly committed to environmental protections; that they strongly believe in marriage equality; and that the war they once had endorsed was actually the mistaken folly of their political opponents.

Often, movements receive scant credit for bringing about such changes of heart. Those who have done the most are likely to be missing from the victory parties, and they are also the most likely to have a pained awareness of the work that still remains to be done.

Yet activists who were pioneers in highlighting the injustice of an issue—and who may well have felt themselves failures at many points along the road—can take pleasure in seeing society come to regard their once-incendiary views as little more than common sense. These one-time rebels may no longer stand out as much as they did when they were marginal and embattled. But from the new majority they helped create, they can command at least a small measure of begrudging respect. Which is another name for success.

Mark Engler is a senior analyst with Foreign Policy In Focus, an editorial board member at Dissent, and a contributing editor at Yes! magazine. Paul Engler is founding director of the Center for the Working Poor, in Los Angeles. They are writing a book about the evolution of political nonviolence. They can be reached via the website www.DemocracyUprising.com.