More Horror Than Hope: The Comic Art of World War 3 Illustrated

More Horror Than Hope: The Comic Art of World War 3 Illustrated

Since the late 1970s, World War 3 Illustrated has channeled comic artists’ outrage at a world of endless war, ecological exploitation, and the brutalization of social relations.

World War 3 Illustrated:

1979-2014

Edited by Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman

PM Press, 2014, 336 pp.

It is safe to say that nothing, in the annals of comic art, has ever resembled World War 3 Illustrated. New issues have come out more or less annually for the past thirty-five years, though they have not always been easy to locate West of the Hudson river; distribution has not been a strong point, but the art, rarely repetitive or clichéd, has been. Year to year and decade to decade, it has been drawn by new hands, in a continual effort to bring along young artists committed to social themes but groping for their own way forward. Luckily for comic enthusiasts everywhere, this remarkable body of work is now collected in an oversized, chock-full volume.

The conceptual starting point for the founders and early collaborators of World War 3 was Masses magazine (1912–17), the original fount for printed “ashcan” art, but also revolutionary optimism and good humor. I’ve always been struck by the hostility of the European experimentalists of the 1913 Armory Show toward their American cousins: ashcanners were viewed as retrograde realists, unable to grasp that the future lay in abstraction. The Cubists and Dadists, and the Surrealists to come, could be revolutionary on their own terms, but the smell of the tenement blocks—or even the sense of a warm summer day in Central Park—did not interest them much as a subject for exploration.

|

|

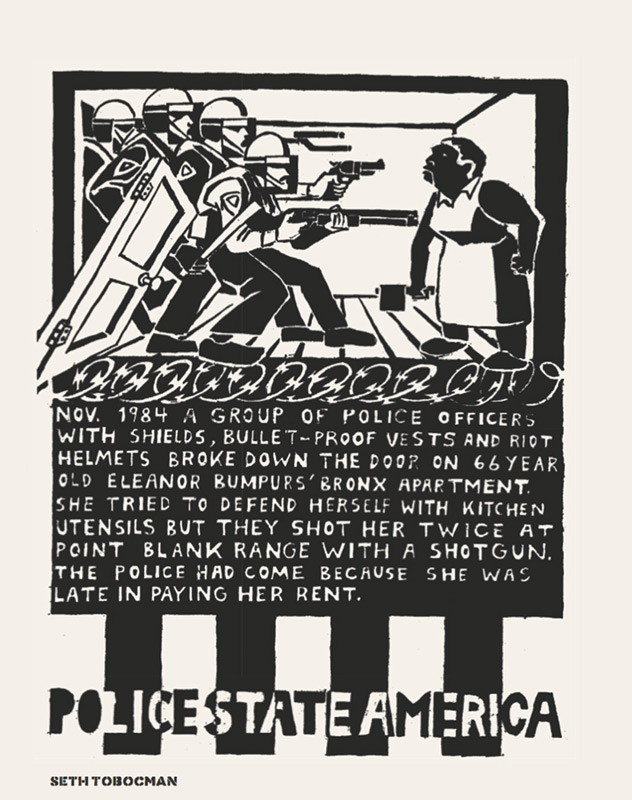

by Seth Tobocman (1984)

|

World War 3 began in a different place, although here, too, war provided a backdrop. Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman grew up in Cleveland, a couple of Jewish neighborhoods away from the creators of Superman; as adolescents, they met Harvey Pekar and published Robert Crumb originals in their fanzine. Kuper and Tobocman looked at the world of the late 1970s with more horror than hope. For them, the optimism of the Summer of Love was long gone, and the shadow of Reaganism was closing in. As much to the point, in the minds of two young artists in Manhattan, the Lower East Side that greeted them was faced with the prospect of an all-consuming gentrification. They created art for Tompkins Square in the way that Allen Ginsberg, joining them in the crowd, created poetry for the struggle, which they ultimately lost.

The power of wealth over human life occupies many pages in this collection, among the most prominent of which are by the severe expressionist Tobocman himself. Ecology, the war machine, violence against women, and the climate of fear engendered by police fill many others. But it would be wrong to see World War 3 as primarily didactic, in the old sense of protest art ordered by some Party committee. The comics capture the artists’ own sense of the moment, and the expressions of outrage—and sometimes hope—belongs to the creators.

|

|

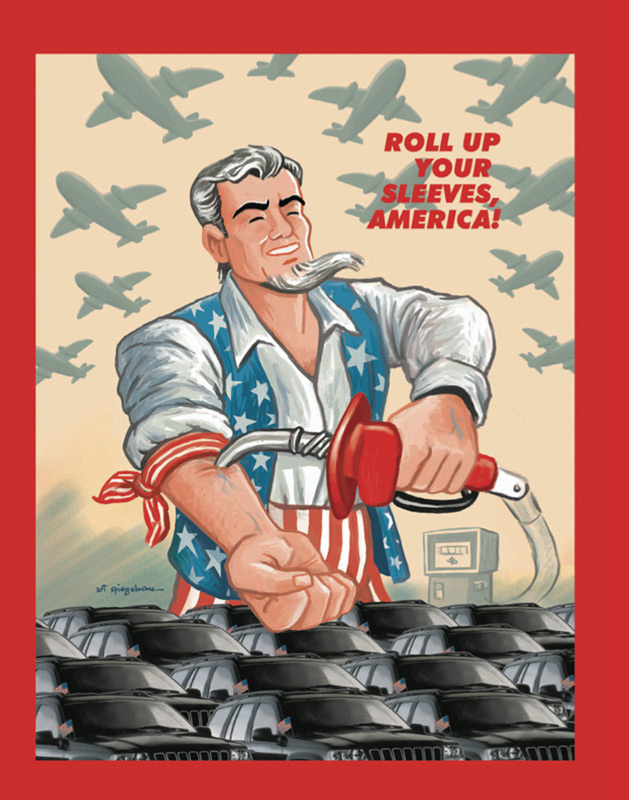

by Art Spiegelman (2002)

|

Kuper, for example, the comic’s best known regular, records the politics and culture of Oaxaca, Mexico, while in a different mode drawing his sardonically brilliant “Richie Bush” (Kuper’s first job in Manhattan was inking the long-running kitsch classic “Richie Rich”). Other artists display similar ingenuity and diversity of interests. Art Speigelman has an unforgettable Uncle Sam rolling up his sleeves to mainline gasoline, with an army of cars below. Tom Tomorrow offers the quiz page, “Are You a Real American?” Nicole Schulman offers grim pages on sexual abuse in South Korea, during the Japanese and U.S. occupations and beyond.

Some of these comics are hard to look at, in the way that challenging art can be demanding. But there are beautiful moments, like Eric Drooker’s take on Occupy, featuring a magic girl on a skateboard hovering over the Brooklyn Bridge, or the four-color pages of Sandy Jimenez looking back, with pain and fascination, at his own life in the Bronx of the 1950s. But to me, nothing tops Sabrina Jones’s mixed-media pages on abortion rights, drawing on her own youthful experiences. Readers of the anthology are bound to find their own favorites.

|

|

by Sue Coe (2012)

|

While the founders justly admired the Masses, I couldn’t help compare and contrast World War 3 to Mad Comics (1952–55), more intense than its Mad Magazine successor (although Kuper did take over the “Spy vs. Spy” feature of Mad Magazine some years ago). Mad’s genius founder Harvey Kurtzman, who would take on Joe McCarthy, guided his artists toward an immanent critique of commercial art and the commercialized popular culture of the postwar era. His vernacular, the hungry but hopeful blue-collar world of the 1930s and ’40s, was being shunted off by something much uglier.

World War 3 portrays this less hopeful world, filled with endless war (and accompanying budgets squeezing out domestic needs), ecological exploitation, and the brutalization of social (especially gender) relations. It’s not nearly as funny as Mad, and that may be the most serious criticism to be made. But it is seriously artistic, a place for artists of any age but especially the young to find a social outlet, providing us with a documentation that we all need to comprehend in our own ways. I’ve been learning as I’ve looked at the pages of the magazine over almost its whole history, and I haven’t stopped learning yet.

Paul Buhle is a retired professor who is now editing his eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth comics, respectively, on Rosa Luxemburg, Herbert Marcuse, and C.L.R. James.