Unsteady Work

Unsteady Work

The central experience of work in the twenty-first century is one of instability. And yet that experience is largely unrecorded in contemporary fiction.

Temporary

by Hilary Leichter

Emily Books/Coffee House Press,

2020, 208 pp.

The literature of work is a literature of belonging. In novels and memoirs set in the cubicles of twenty-first-century offices, there is a struggle between the embrace of the collective and the conflicting desires and incentives of the individuals within it, between diving into a well-developed, gossip-rich office culture and bearing down on the more difficult task of defining the self. The works that make up this genre are often coming of age stories, in which a company gives the narrator a trajectory, a vocabulary, and a context—the building blocks of a life—and only slowly, devastatingly, do they begin to discover the limits of their new identities.

Everyone has their place in an office. They are the employee who once mistakenly sent a reply-all talking trash about a coworker, or the staffer obsessed with upgrading to a better model of swivel chair (as one character is in Joshua Ferris’s 2007 office novel Then We Came to the End). They are the CEO, or the CTO, or the VP of social impact. Some of them are simply, terrifyingly, “HR.” All the team-building exercises do, in fact, bring everyone together, even if only by giving them something to disdain collectively. Work enters every aspect of the employees’ identities. They start to dress the same way, listen to the same music, use the same industry slang and buzzwords, and measure their lives against the same systems of value. Nothing can harm them—except layoffs.

Still, the office novel only scratches the surface of work’s complex bearing on a life, a self. It is not exactly concerned with the office so much as with salaried employment. Its heroes are college-educated knowledge workers in buoyant job markets. They have W-2s and good benefits. They can afford to worry about their levels of satisfaction and to discern existential questions in the rhythms of well-remunerated daily life. Much of this experience will be a distant memory to those workers who’ve pivoted into more precarious freelance work over the past few decades, the legions of independent contractors and permalancers who perform many of the same functions as staff and contribute to the same bottom line, but without the same inclusion in the organization.

For those who string together gigs in the sharing economy or perform microtasks on platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, the white-collar employee’s genteel ironies—oh the free snacks, the lavish corporate-bonding retreats—are as relatable as The Age of Innocence. The central experience of work in the twenty-first century is one of instability. And yet that experience is largely unrecorded in contemporary fiction.

Hilary Leichter’s Temporary is the rare novel that reckons with unsteady work. If the book is a surreal, absurd, sometimes self-defeating entry in the office genre, that is because temporary work is all those things. “I have a shorthand kind of career,” the opening pages declare. “Short tasks, short stays, short skirts.” The wry unnamed narrator progresses from placement to placement, bolstering her résumé and attempting to fake it until she makes it. She lives by an inspirational quote—“Nothing is more personal than doing your job”—which she also identifies as nonsense she got from the back of a granola packet. Landing a permanent job here has little to do with good work or persistence. The characters term the ascent to a staff position “the steadiness” and talk about it in mystical tones. It’s an elusive state: the narrator’s mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother each spent a lifetime “filling in,” never advancing beyond temp status.

Leichter has almost no interest in realism; she is interested in the absurdity of corporate language, the kinds of phrases that are used to justify loose employment bonds and precarious conditions, which she applies to increasingly bizarre and fantastical scenarios. The first assignment the narrator describes is filling in at Major Corp, a deliberately cartoonish Goliath organization. Instead of performing traditional temp duties, however, she finds herself covering for the chairman of the board. It is, more or less, a breeze:

I sign documents I don’t understand, sit in on conference calls, stack memos and stamp the dates, fiduciary and filibuster and finance and finesse and fill the office walls with art selected from a list of hip emerging painters, and finish each assignment before anything can be explained in full.

In the middle of an impenetrable board meeting, someone suggests that “maybe we could just put a pin in it”—to “audible sighs of relief.” The executives then proceed to produce pins and push them into their briefcases, concluding the discussion. There’s Leichter’s taste for the absurdly literal: What would the world be like if we really meant what we said at work? And would the effects be much different? There’s always a nasty sting. On the next page, the narrator passes a woman sobbing outside the office and considers that “in one of my morning meetings, I probably put a pin in her employment.”

From here, things get a lot weirder. (After all, isn’t Major Corp, with its corporate irresponsibility and unthinking, barely informed leaders, a little too much like a real company?) At the end of the narrator’s placement, the chairman dies, and his spirit asks her to carry a portion of his ashes around with her in a necklace charm; he periodically manifests to give her guidance and moral support. He’s with her on her next assignment, where she covers for a crewmember on a pirate ship. This is followed by a brief stint as a human barnacle (“filling in for a species on the brink of existence,” her new colleagues explain), a gig distributing pamphlets for a witch, as well as some time moonlighting as a seven-year-old boy’s mother. At one point, she gets a job inexplicably opening and closing doors in a house; after a while she realizes she has been “filling in for a ghost.”

Each stranger than the last, these events unfold with the clarity of a dream. When Leichter stretches the language and rules of the workplace to describe the order of business on the pirate ship, she finds it’s a pretty good fit. “Ahoy,” says the narrator on her first day; it is literally an onboarding. The pirates hijack ships, take prisoners, wear eye patches, and force each other to walk the plank. But they also talk in the learned tones of professional reasonableness. “Let’s find a solution that suits us both,” says one particularly violent character amiably. The narrator doesn’t know how pirates make money, but, she explains, “I rarely have insight into my employer’s overarching projects.” When she notices problems, she has the same attitude: “Like any new company, they’re still working out the kinks.”

Still, Leichter’s pirates frequently expose the more brutal side of working life. “Working remotely is what we call being dead,” a colleague tells her. “Pirate lingo.” The narrator also discovers that the pirates have a literal interpretation of the notion of “severance.” She’s not disturbed to discover that everyone on the ship is armed with weapons, ranging from daggers to cannons. It comes as a relief, after working in so many offices where no one knew who was really the boss.

The ship also serves as the setting for a serious identity crisis. Filling in for someone, the narrator frets, is not just about assuming their duties and making sure that the work gets done. It’s about taking on their entire role, which means emulating aspects of their personality and working habits down to the smallest quirk, understanding the office culture the same way they did, and making every effort to fit neatly in. “It takes an aggressive empathy to accurately replace a person,” the narrator says, fearing that she’s falling short of “Darla,” the pirate she’s been hired to cover. “A person is a tangle of nerves and veins and relationships, and one must untangle the tangle like repairing a knotted necklace and wrap oneself at the center of the mess.”

The feeling of impermanence spreads through her whole life. She feels awkward visiting an old friend’s home, where she’s invited to stay for the evening and watch a movie:

It’s not for me, this kind of moment. Something inside me can’t be contained by the shape of her house, her life. Something about me does not and will not fit. I feel myself protruding like a broken bone, breaking through the skin. Perhaps it’s a matter of qualifications, the way they both certify and prohibit, the way I find the fullness of my life constantly halved, constantly qualified.

Constantly adapting to new workplace cultures and their expectations, there’s never time to put down roots. The most moving section of the book is the narrator’s placement as a little boy’s temporary mother. He hires her to do an eerily accurate impersonation of a woman who feels stunted by the onset of motherhood: “Sometimes I’m supposed to scold him or punish him, and sometimes I’m supposed to yell for no reason, get sad, and stare out the window.” She grows to love the little boy and finds herself spending her own money on medications and toys for him. But the little boy is her employer, and he has to remind her, pitilessly, that this is an employment relationship. She’s crossed a line. And soon he lets her know that her services will no longer be required.

Being successful at work requires all-in emotional investment in the performance of the work; but that only reminds her of what it’s like to experience love, family, belonging, and the stability and permanence that she’s been acting out—and that makes the work much harder to bear. Ever since the “First Temp” filled in for someone, we’re told, “she lived in the space between who she was and who she was meant to replace.” It is no wonder that the narrator ultimately gives up on the

whole system.

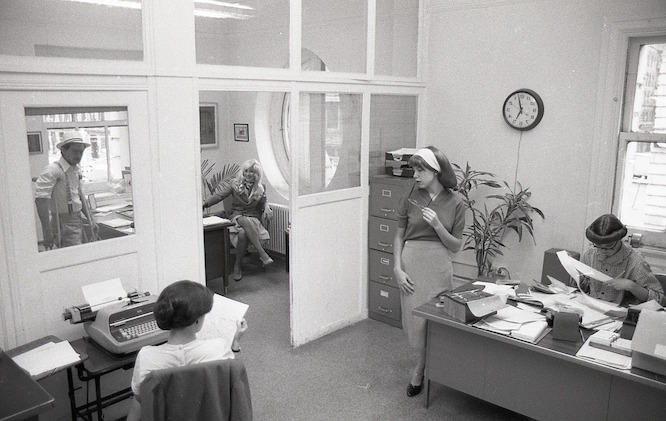

Temporary is very good at making fun of corporate culture, but its depiction of temporary work is not so sharp. The vision of temping we get from the book is highly traditional and centered on an old-fashioned staffing agency. “My temp agency,” the narrator explains, “is an uptown pleasure dome of powder-scented women in sensible shoes” with “manicured hands.” This obviously retro vibe is reminiscent of postwar agencies like Kelly Girl, Olsten, and Manpower Inc., which sent young women into offices for a week here and a week there to cover for vacationing or sick staff. The agencies gave their temps advice on how to dress; some even sent their “girls” out wearing white gloves to emphasize the pristine quality of their service.

There’s a nostalgia too, in the idea that a traditional agency would provide a steady stream of jobs, which could be scheduled end-to-end to form near-continuous employment. “With trusty carpal alchemy, they knead my resume into a series of paychecks that constitute a life,” the narrator rhapsodizes. The assignments come through reliably on Fridays and Mondays. “Like clockwork, like something sturdier than time, the agency allots my existence.” Although she doesn’t stay at one company long enough to settle in, the work itself is somewhat dependable here.

Needless to say, this system no longer exists—if, in fact, it ever did. The postwar temp agencies notoriously painted a much rosier image of temping than they ever truly offered. Temps interviewed by the workers’ rights organization 9to5 in the 1970s frequently complained that they couldn’t get enough hours to make ends meet, even if they signed up with multiple agencies. One temp described getting work as a “roulette wheel.” This wasn’t an accident: agencies took care to ensure that temps rarely got enough work to qualify for sick pay or vacation days.

Temporary work has always entailed a level of hustle. There’s the job, and then there’s the job of getting the next job, and the next job, and the next one. It never ends. In the dystopia that Leichter imagines, temps are only ever filling in for absent full-time staff, whose return brings to an end the temp’s dreams of taking up a permanent position. But much scarier is the reality of the sprawling 1099 economy. There are the large numbers of workers who have a longstanding employment-style relationship with a company but who are kept ineligible for benefits by the fiction that they are not technically staff. There are the subcontracting companies that dispatch workers to even bigger companies to provide services that range from cleaning to IT maintenance to fact-checking. Then there are platforms like Upwork and Fiverr, where professionals compete to take on piecework on an ad hoc basis. And there are the gig economy apps: Uber, TaskRabbit, Postmates. Rather than a stark divide between temporary and permanent employees, there are many gradations of temporary work. And when companies use temps to cut down on the number of core staff in the name of flexibility, they add to complex dynamics between temporary workers and staff. The permanent positions are not so permanent, it turns out.

It’s tempting to consider the proliferation of precarious work since the last recession a blip, to consider temporary work itself a temporary phenomenon. But as Louis Hyman has traced in his history Temp, corporations have been retooling their workforces toward “flexible” work for several decades—a process that has only accelerated since 2008. This year, millions of Americans have suffered the shocks of a global pandemic. In the space of two weeks in March, businesses across dozens of states shuttered, entire staffs were furloughed, and about 13 percent of the workforce filed for unemployment. Permanent employment is no longer the norm and has not been for a long time. Fiction rarely reflects this, largely overlooking the realities of work as so many people experience it: as scarce, unpredictable, poorly paid, dangerous, demoralizing. To read even a bleak novel like And Then We Came to the End at this moment is to get a luxurious glimpse back at disappearing conventions—the cubicle etiquette, the intra-office gossip, the time-wasting at pointless meetings.

Temporary ends with a flourish: its final chapter takes the form of an “exit interview.” It’s a lovely touch, typical of the way Leichter commits to her conceit of filtering the narrator’s entire experience through the rituals of employment. “When I die,” the worker says in one of her responses, “it will be like leaving a job without time to clear my desk.” It is not so difficult

to imagine.

Laura Marsh is the literary editor of The New Republic.