The World of the Radical Right

The World of the Radical Right

A roundtable discussion on the global networks and political strategies of nationalist conservatives.

The following is an edited transcript of a panel held on February 21 at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perry World House on the forthcoming book World of the Right: Radical Conservatism and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press). The discussion, moderated by Sam Adler-Bell, features three of the book’s co-authors—Rita Abrahamsen, Srdjan Vucetic, and Michael C. Williams—and concludes with questions from the audience at the event.

Sam Adler-Bell: I’m excited to talk about this excellent book, World of the Right: Radical Conservatism and the Global Order. I read a lot of books about the right for the Know Your Enemy podcast, and this one is both analytically and stylistically clear, which you don’t usually get together.

Michael C. Williams: The goal of this book is to ask to what extent the radical right, which is almost by definition nationalist in its focus, is a global phenomenon. Parties and movements that identify with the radical right are popping up all over the world. Is this a coincidence? Is it a conspiracy? Is it something more complicated?

We try to overcome three common prejudices about the right. The first is that its resurgence is the fault of technology and the digital age. Undoubtedly, but that’s not enough. The second is that it is simply a result of economics—of the “left behinds” rising up against their overlords. Also important; also not the whole truth. The third is that the right is stupid. In reality, it is complicated and sophisticated.

The contemporary right is nationalist and local. But it is also global, both conceptually and organizationally. What we call the “world of the right” is the outcome of a fifty-year-old ideological project. We trace it through the ideas of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, who argued that political power is never simply a matter of coercion, but also of consent. And in the production of consent, culture is vital. Any hegemonic order relies upon a naturalized understanding of the world. And for opponents of that order, it is crucial to create a counter-hegemonic strategy, an intellectual world, and a set of institutions.

In the 1970s, the French far-right figure Dominique Venner called for “a Gramscianism of the right.” This idea was rooted in an argument about contemporary politics, social life, and globalization: that the world that we live in is dominated by “managerialism.” The idea of managerialism, which emerged out of the anti-Stalinist left in the 1920s, was picked up by members of the American right, such as James Burnham, in the 1950s. They argued that a “new class” of technicians, lawyers, accountants, and business executives had more in common across countries and cultures than with anyone else within those countries and cultures. It is opposition to that purported class that forms the core conceptual underpinnings of the contemporary right.

Rita Abrahamsen: The right’s counter-hegemonic struggle has not only been at the level of ideas. It has also been diligently pursued in practice. Social media and the digital universe have been crucial, but the struggle has also been fought in the more traditional battleground of universities and academic publishing. In the last decade or so, we’ve seen a massive expansion of radical right-wing publishing houses. They have reissued classic right-wing texts and published new ones. The English-speaking publishing houses have been at the forefront of translating the French radical right. They take ideas and the counter-hegemonic struggle very seriously. They’re trying to construct an ideological history that distinguishes them from fascism. They are trying to say, “We deserve a place at the university.” In fact, they’re trying to change the university.

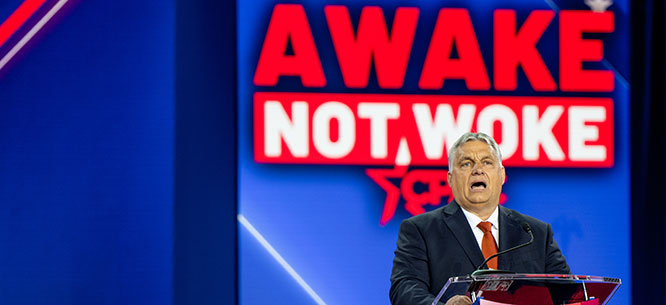

In Europe, they are even trying to set up new universities. At the forefront of this initiative is Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, where at least two new universities have been established explicitly to educate and train the new radical right elite. (The radical right is anti-elitist only insofar as the elite is schooled in old liberal values.) Another example is from France, where Marion Maréchal, the niece of Marine Le Pen, has set up a school in Lyon dedicated to training a new ultra-conservative elite. There are many more. These various institutions and universities are networked and have partnerships with elite institutions around the world.

There’s a lot of diversity on the right, but we can point to at least three commonalities in their vision of world order.

First, the radical right is anti-globalist, but not anti-internationalist. They wouldn’t necessarily abolish all of our international institutions, like the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. They rather seek to change them from within so their policies allow greater state sovereignty. We are already seeing the effects of these efforts in the European Union.

Second, the radical right believes that the world is made up of different cultures or civilizations, which are the world’s true value. Global liberalism, they claim, has flattened and ruined this diversity. This belief allows the radical right to ally themselves with peoples and states in the Global South who also feel that their cultures are being destroyed or undervalued by liberal universalism.

Finally, the radical right believes in multipolarity—not the multipolarity of international relations theories, but of civilizations. Their vision is of a world consisting of different civilizations that would cooperate when necessary but wouldn’t move toward a common culture or universal values. This vision allows them to form alliances with other cultures or states, including illiberal ones like China and Russia, that hold similar civilizational views.

Adler-Bell: My understanding is that the work on your book began in 2015, which was a fascinating moment to study global reaction, with the twin convulsions of Brexit and Trump coming the next year. What inspired you to undertake this project in that moment? What currents were you tracking when you embarked on it? Did you know something we didn’t about how important right-wing movements were going to become on the global stage?

Srdjan Vucetic: I’m from Bosnia and Herzegovina. My life has been perniciously affected by various forms of the radical right. We’re Cassandras, walking around with catastrophic thoughts constantly. The year 2015 was as good as any to think about horrible outcomes.

Abrahamsen: When we started, Trump was a worst-case scenario. We were having conversations about how similar things seemed to be happening around the world. People seemed to be talking about what was happening in France, in Germany, in the Scandinavian countries. But nobody was talking about why political movements seemed to be emerging in similar ways in very different places. We picked up on some of their networks, and we started to consider whether what most people were calling “populism” was something more.

Williams: There was also a certain exhaustion in the “normal” conservative world, both intellectual and institutional. Many scholars claim that the radical right doesn’t tend to win because it defeats its adversaries; it tends to win because the more moderate right ceases to fight it. We suspected that was already beginning to happen.

Adler-Bell: In the American context, the fusionist consensus [between economic libertarianism and social conservatism] of the 1950s and ’60s feels dead, or at least very quaint compared to the populist radical right-wing forces that have taken up much more space in our politics in the last couple of decades. This is perhaps a good place to ask a definitional question. You refer to a “radical right,” which is distinct from both mere conservatism and fascism. Why that term?

Williams: Two primary tendencies define the radical right as a distinct form of politics. The first is that it is often suspicious of, if not openly hostile to, liberal democracy. Unlike the far right it does not seek to overthrow it violently, but to build variations on what Orbán has called “illiberal democracy.” Most postwar traditional conservatives had made their peace with liberal democracy as a governmental form. The radical right has not.

The second important distinction is that conservatism is traditional: it believes there are things of value that one must hang onto. Much of the contemporary radical right regards contemporary society as so far gone down a ruinous pathway that only a truly radical solution will work. That tendency has always existed to some extent on the American right. But it largely emerged with the paleoconservatives in the mid-1970s, who came out against the fusionist consensus.

Abrahamsen: Another important distinction is between the radical right and the extreme right. It’s not hard and fast; the two shade into each other. The fascists who believe in violently overthrowing the current order are not our main preoccupation. As much as the radical right and the extremists might legitimize each other, we’re concerned with those who have covered up their tattoos and now take portraits in front of bookshelves.

Adler-Bell: I’d like to talk more about Gramsci. On the face of it, it’s counterintuitive that an Italian Marxist theorist and partisan who died in 1937 would play such an important role in cohering the ideas of the global right. You suggest that they have turned Gramsci on his head. What does that mean, and why are Gramscian concepts so useful for these movements?

Vucetic: Gramsci talks about two types of wars: a war of maneuver and a war of position. A war of maneuver is the storming of the Bastille. A war of position, by contrast, is trench warfare that takes time, decades even. It is a slow march through the institutions, including political institutions, but perhaps more importantly institutions of culture, such as the media, the arts, publishing houses, and educational institutions.

This war of position is where we see the radical right shining within and between nations. There’s a unity of purpose here that didn’t exist before. It was inspired by the French new right, and it spread from Western Europe into Eastern Europe and the United States, and now across the globe. In India, we have the head of the RSS [the cadre-based organization affiliated with the ruling BJP] using terms that are associated with this right-wing Gramscianism.

Abrahamsen: It is striking how many right-wing intellectuals in different parts of the world have explicitly turned to Gramsci. One of Jair Bolsonaro’s principal influences, the philosopher Olavo de Carvalho, was called the Gramsci of Brazil. He set up his own series of online courses, and a number of men in Bolsonaro’s government graduated from his program.

The term “culture war” is often used and abused, but the radical right believes the culture must change in order for common sense to change, and only then will material politics change. You don’t win elections at the ballot box; you win them by changing the way we think.

Adler-Bell: You write that adherents of the global managerial thesis believe that “the essence of contemporary world politics is not the age-old story of realist power politics, the liberal tale of progress through institutions, or the corrosive spread of neoliberal capitalism. It is instead the rise to power of a global liberal managerial elite, the so-called ‘class of experts’ and bureaucrats.” Where does this worldview come from? Why is it so important for contemporary right-wing movements? And to what extent does it describe reality?

Williams: The key to any counter-hegemonic strategy is to explain to the people you’re seeking to mobilize the world that they live in. Why are these things that make you uneasy happening? The managerial thesis provides an explanation. The right is not simply opposing some abstract notion of neoliberalism; it’s global managerialism, and one of its crucial elements is that it has global managers—what Carl Schmitt referred to as an identifiable enemy.

The global right has a rather loose relationship to empirical truth. But the theory must be plausible enough to connect to the real world. Counter-hegemonic strategies can’t be fantasies. This strategy also helps explain why it isn’t simply people who have been economically disenfranchised that are mobilized by the radical right. There are a lot of people who are doing very well in the current world order who have been convinced by the radical right because of cultural issues that irritate or infuriate them.

Vucetic: Michael mentioned that liberal managerialism comes from 1920s anti-Stalinist left thought. I was born and raised on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain, where we had this debate in the socialist context. Milovan Djilas, the Yugoslav dissident, wrote a book in 1957 called The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System. It had lots of overlap with James Burnham. There’s a resonance on the left, as well, which has its own critique of liberal managerialism, though perhaps not global liberal managerialism.

Adler-Bell: I want to ask about the relationship between radical right movements and what you call the liberal international order. You acknowledge some of the factors we tend to rely on to explain the crisis of liberal hegemony, such as neoliberal dislocation, the professionalization of party politics, and the rise of illiberal powers like Russia and China. But you add to this account in important ways. You write, “While we agree that the hierarchical, unequal nature of the liberal international order is a condition of possibility of the global right, we argue that the radical right has built powerful transversal global alliances based on a logic and discourse of difference and diversity, rather than claims to Western liberal superiority.” That may sound a little counterintuitive to people who have thought of the right as advocating Western supremacy.

Abrahamsen: Right-wing radicals are what we call “differentialists,” not universalists. Their idea is: we have our cultures; you can be whatever you like, as long you don’t interfere with us, you don’t come here, and we acknowledge each other’s differences. The radical right is now closely aligned with traditionalists and nativists in the Global South, where the idea of the right to one’s culture, tradition, and values has found purchase. In the book, we look at resistance to impositions from the West, including the UN’s policies on gender equality and gay rights. Russia has also played this game quite effectively, opposing Western imperialism and appealing to cultural difference to form alliances in the Global South and thus disrupt and destabilize key elements of the liberal international order.

Vucetic: The discourse of civilizationism emphasizes mutual respect. That goes a long way. Russian diplomacy in Africa is a good example. Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, went on an African tour in July 2022; the Russian Duma had a Russia–Africa conference the next year, sharing ideas about anti-Western imperialism, civilizationism, and Pan-Africanism, among other subjects. This should not be underestimated, just as we should not underestimate Russia’s courtship of white supremacists in the United States since the 1990s. These relationships have far-reaching consequences.

Williams: This commitment to difference allows the radical right to escape fascist notions of civilizational or racial superiority. It is crucial to the contemporary right’s political legitimacy to refute those accusations. In fact, they argue, liberals are the ones claiming superiority today. The International Criminal Court, the World Bank, and other liberal institutions tell people around the world how to live their lives. As Alain de Benoist of the French new right said: “Diversity is the treasure of the world, and egalitarianism is killing it.”

Audience Question: I’d like to hear more about how new universities and institutions such as those in Hungary credential global right-wing figures.

Abrahamsen: Right-wing think tanks in particular have been instrumental in getting these ideas into public discourse. In the United States, the Claremont Institute and Hillsdale College are two of the most important. In France, Marion Maréchal’s Institute of Social, Economic and Political Sciences has been very influential. It has also set up a sister institution in Madrid. They are closely linked to politicians (the Vox party in Spain, National Rally in France). In Hungary, there is the Ludovika University of Public Service and the Mathias Corvinus Collegium, which is an incredibly powerful institution. In 2020, it got $1.7 billion from the Hungarian government. There is also a new think tank in Brussels funded by the Hungarian government, which is linked to the Mathias Corvinus Collegium. It seeks to burst the cozy Brussels bubble, where everyone agrees that we must have greater European integration. There are indications that this think tank was actively involved in the recent anti-EU farmers’ protests in Brussels.

Williams: If you’re looking to credential counter-institutions, the first thing you need to do is delegitimize existing institutions. That is not easy, but the radical right’s anti-elite strategy is part of its attempt to do so. In addition, you need to create an entire ecosystem of counter-institutions, not only for training people for government but to employ them when you’re not in power. You need to have think tanks for them—what Sam on his podcast calls the “conservative welfare state.” For all these graduates who can’t get jobs in the real world, the think tank world is now so big and so well-funded that they can make a living in it until they do something else.

Audience Question: How much staying power does the far right have? How long and protracted of a fight are we going to be in, and what does the U.S. election mean for this?

Vucetic: Twenty years ago, people who studied right-wing populism and the extreme right were relaxed. They often concluded that institutions in the Atlantic World were strong; that the best the far right could do was become a junior partner in a coalition government in some small European country. That has changed, clearly. All eyes are on the November election. The repercussions will be huge. This past year was a watershed moment for the radical right in Europe. These parties are not going anywhere. In fact, they’re probably getting stronger.

Abrahamsen: You see its staying power also in the way that the radical right is becoming more normalized. After every election in France or Germany, we feel relieved that they didn’t do quite as well as we had feared. But they’re still doing an awful lot better than they did in 1990. The radical right is pushing old-fashioned conservatives further to the right. In order to tackle the challenge of the right, the rest of the political spectrum moves in its direction.

Williams: British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, leader of the UK’s Conservative Party, has been pushed far to the right, both by the UK Independence Party and Reform UK, and by members of his own party. A number of them went to a meeting that we attended last May in London called the National Conservatism Conference, or NatCon 2023. There, they rubbed shoulders with the head of the Heritage Foundation, representatives from the Hungarian government and related think tanks, and a variety of other figures on the global right. Even trench fighters within party politics in one small state are highly conscious of belonging to a like-minded international community. Even if they disagree, they disagree on issues that they think are important.

Adler-Bell: NatCon, which has been held multiple times in the United States and once in Hungary as well, is distinctive because it is where the reconciliation between the radical right and the more mainstream right, or the dregs of the mainstream right, takes place. The old school right-wing fusionist Heritage Foundation can shake hands with an Orbán functionary and say, “We’re on the cutting edge, too; we can see that they’re going right, so we’ll follow them.” NatCon is a great example of how, as Rita said, the political spectrum is being pulled to the right.

Audience Question: Why hasn’t Hungary pulled out of the European Union? Why don’t we see more forces within the European Union trying to break it up?

Williams: One of the main strategic shifts on the radical right in the last few years is a move away from hostility to institutions and instead trying to take them over. The evolution of Marine Le Pen’s position on the European Union exemplifies this trend: while earlier she spoke about wanting to kill it off, now she says she wants to pull it back to being a sovereigntist organization—essentially, facilitating trade with a heavy hand of national state supervision. This gets us into larger arguments happening on the right about whether global capital will force them into line with various transnational structures.

Vucetic: It is a true puzzle why the European Union tolerates Fidesz and its coalition partners. However, part of those billions of dollars that are being invested in Ludovika and Mathias Corvinus Collegium are coming from the European Union. One explanation is that the European Union is trying to appease figures like Orbán, lest they join forces with Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, which they’re doing anyway. The political project of Orbán’s government is to focus its energy on an issue du jour—whether it’s migrants, non-Hungarian minorities, or the European Union—while at the same time protecting domestic capital and trying to bring Russian and Chinese capital into the country. The European Union is now a means to an end, and that end is a new civilizational state. These visions are becoming increasingly real among people who hold political power.

Rita Abrahamsen is a professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. Her research interests are in the intersection of African and global politics, security studies, and postcolonial political thought.

Sam Adler-Bell is the co-host of Know Your Enemy.

Srdjan Vucetic is a professor at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa. His research interests lie in international relations theory, security studies, and foreign and defense policy analysis.

Michael C. Williams is the University Research Chair in Global Political Thought in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. His research interests are in international relations theory, security studies, and political thought.