The Problem With a Job Guarantee

The Problem With a Job Guarantee

Building working-class power through full employment is a worthy goal, but there are better strategies for creating and sustaining a tight labor market.

Read responses to this article by Dustin Guastella and Mark Levinson here.

The time has come to abandon a political proposal that the left has advanced in Europe and the United States for almost 200 years: that the government should guarantee a job to everyone who is looking for work. While the goal of durably tightening the labor market is important, a federal job guarantee is a bad strategy for achieving that objective.

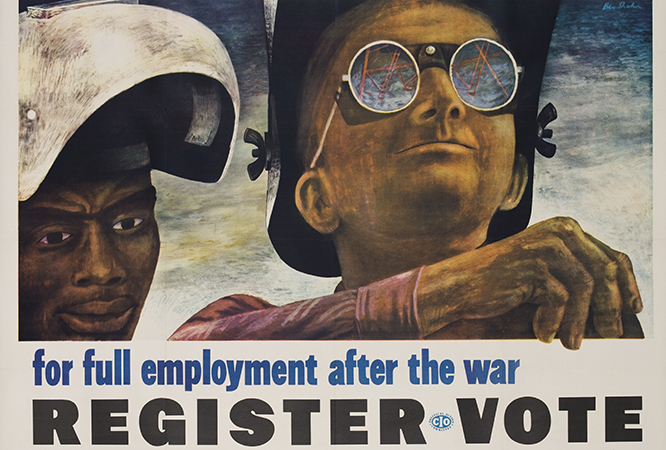

The demand dates back to at least 1848, when the early socialist Louis Blanc persuaded France’s provisional revolutionary government to establish public workshops that would provide employment to anyone looking for work. While the plan was not implemented effectively, the demand for government-created jobs for the unemployed became a part of many left-wing wish lists. It was in the platform of the U.S. Social Democratic Party in 1900, and the Unemployed Councils in the 1930s agitated for government-funded public works to pay the unemployed union wages. President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to this pressure by establishing the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and other employment programs.

As the Second World War ended, there was widespread fear in the United States that mass unemployment would return. The labor movement and its allies fought to pass full employment legislation that would guarantee jobs to everyone who wanted to work. The Employment Act of 1946 was passed after extended debate, but it kept only a rhetorical commitment to full employment.

This drama was repeated in the 1970s, when organized labor and civil rights leadership mobilized to pass a federal job guarantee as proposed by Augustus Hawkins in the House and Hubert Humphrey in the Senate. The legislation approved in 1978 was once again watered down to eliminate an actual federal job guarantee.

The idea of a federal job guarantee lives on today. It was included in the proposal for a Green New Deal that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her colleagues submitted to Congress in 2019, and it was also advanced by Bernie Sanders in his 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. The demand has been pushed by advocates of modern monetary theory and embraced by a number of African-American leaders. As recently as February 2024, Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley offered a resolution in support of a federal job guarantee in honor of Black History Month.

Advocates for a job guarantee have persistently argued that unemployment and competition for scarce jobs fuel conflict between white workers and workers of color, both native-born and immigrant. Employers exploit these tensions to weaken or defeat worker organizing, and right-wing politicians have won elections by mobilizing racist and anti-immigrant anxieties.

If the government provided a decent job to everyone looking for work by managing a bank of job openings that would expand and contract in response to private-sector openings, the labor market would always be tight. Competition for decent jobs would be greatly reduced. It would be far easier to build solidarity among workers across ethnic and racial divides, and a more unified working class could win victories in both the workplace and the political arena.

Advocates often claim that a single piece of enabling legislation could effectively execute a job guarantee. The proposal also polls well: a 2019 Harris poll found that 42 percent of a national sample somewhat support and 36 percent strongly support a federal job guarantee.

These factors make a job guarantee seem like a realistic political demand. But appearances are deceptive. In reality, it would be difficult to implement, and its political popularity is illusory. Many of its supporters believe that society owes nothing to those who are not earning a wage. It would also be extremely difficult to win because it creates unified and militant opposition from businesses of all sizes. There are better strategies for creating and sustaining a tight labor market.

Implementation Problems

In pre-industrial England, the basic unit of local government was the parish, which encompassed anywhere from a few hundred people to more than 100,000. Under the Elizabethan Poor Law, each parish was obligated to care for the indigent and the unemployed. One technique used in rural parishes was the roundsman system, in which crews of unemployed men traveled through area farms to provide whatever work farm owners needed. The roundsmen received some combination of cash relief from the parish and payment from the farmer as long as they showed up regularly to provide the required labor. In some cases, the labor of the unemployed was sold at auction to the farmer who offered the highest price.

Neither the unemployed nor the farmers were enthusiastic about this early form of a job guarantee. For the unemployed, receiving some income was obviously preferable to the possibility of starvation. However, this work offered little opportunity for either stability or promotion. Sometimes a roundsman impressed his employer enough to be offered a regular job, but that was hardly the norm.

In turn, farmers often complained that the roundsmen were lazy and did work of poor quality. This is hardly surprising; work effort is linked to the promise of continued employment, and roundsmen knew they would likely work for a different farmer soon. They had no incentive to work hard, especially since their compensation was generally well below the payment for regular farm workers. It was like the old Soviet joke about low-wage work: “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work.”

While the roundsmen system was eliminated by the New Poor Law of 1834, similar programs have persisted to the present day. “Workfare” is the current term for programs that make income assistance contingent on the recipient showing up to do some kind of labor. The most extreme version of workfare occurs in prisons, where incarcerated people make license plates, do laundry, or prepare meals, for example. In federal prisons and most state prisons, incarcerated workers are paid far less than workers on the outside. In 2023, California proposed raising the minimum hourly compensation for prison laborers from 8 cents per hour to 16 cents. Those filling the most skilled jobs would be raised from 37 cents to 74 cents. Meanwhile, California’s statewide minimum wage is $16 an hour.

Workfare programs for those who have not been convicted of crimes are not as extreme, but they are generally designed to punish those enrolled. Such programs assume that the people in need of public assistance do not have the skills required to land a regular job. They are imagined to lack punctuality, self-discipline, and respect for authority; workfare assignments are intended to remedy this by requiring recipients to show up on time and obediently fulfill what are typically unpleasant work tasks, often for well below the minimum wage. Unsurprisingly, these workfare programs have been plagued with racism and misogyny.

Workfare supporters usually embrace what Margaret Somers has called “market justice,” or the belief that the market produces inherently just outcomes. They argue that those who have great wealth are being rewarded for hard work and self-discipline—even if their wealth was inherited—and that those in poverty have ended up there because of some personal failing that has prevented them from earning enough to join the middle class. It follows that, for those of this ilk, the poor must learn self-discipline and ambition, and workfare can teach the skills required to make people self-sufficient.

However, while workfare is often proposed as the solution for those left behind in poverty, it is rarely implemented on any significant scale. Workfare was emphasized in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act passed under Bill Clinton in 1996, but by 2002 there were only 40,000 welfare recipients in the entire country enrolled in workfare jobs. The obstacle is that workfare is expensive, especially compared to sending small amounts of public assistance to those who qualify. Workfare requires a high staff-to-client ratio precisely because of its focus on discipline. For every ten or twelve workfare employees, there must be a supervisor who can assure that their charges are actually working, and supervisors must be paid enough that they will not join their charges in slacking off. These supervisors, in turn, must themselves be supervised by even more highly compensated managers.

Advocates for a government job guarantee generally despise workfare. They oppose substandard compensation in government-provided jobs, arguing that employees should be paid union wages. However, even the most successful government jobs programs, such as the WPA, have typically paid well below prevailing wages in the private sector.

The WPA itself did not aspire to hire all of the unemployed. Its peak employment of 3.3 million was reached in 1938, when 10 million people remained on the unemployment rolls. Some analysts have argued that the program operated as a kind of safety valve to contain radicalism by hiring the most militant and talented among the unemployed. Moreover, the severity and duration of mass unemployment meant that the WPA could hire skilled managers to supervise multiyear construction projects. Many WPA workers received meaningful assignments in which they could learn or practice important skills.

Recently proposed federal job guarantee programs would not be able to emulate the WPA’s successes because they are intended to operate countercyclically. The number of public-sector jobs would reach its highest level at the bottom of the business cycle and its lowest level at the top. In such a program, the number of guaranteed jobs would expand and contract, because reliance on public-sector jobs when the private sector needs labor would produce inflationary pressure in an overly tight labor market along with an intense political offensive from businesses to shut down the guarantee program.

Organizing an accordion-like job guarantee also presents severe logistical challenges. As of July 2024, the number of people counted as unemployed in the United States is 7.2 million. If we assume that half of this is short-term unemployment that will be resolved relatively quickly, then the guarantee would need to provide 3.6 million jobs. However, if the economy went into recession and the unemployment rate climbed to 8 percent, the number of jobs needed might easily double to 7.2 million or even more. In The Case for a Job Guarantee (2020), Pavlina R. Tcherneva suggests that the guarantee might have to provide as many as 15.4 million jobs.

That variability would make implementation very difficult. Many of the guaranteed jobs need to be nonessential so that there would be minimal disruption as the program contracts when private demand for labor increases. Take the most recent large-scale experiment with public-service employment in the United States, which was established by the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) during Jimmy Carter’s presidency: the number of people employed by the program reached a peak of 750,000 in 1978, but many of those jobs, including maintenance of public parks and buildings, involved very little skill development and resembled jobs in workfare programs.

Proposals for a job guarantee leave unanswered the question of who will create these millions of nonessential jobs. This could not be done from Washington, D.C., without creating a new federal entity with offices in all fifty states. Advocates usually propose that the federal government would provide the funds, but state and local governments working with nonprofit organizations would be responsible for creating jobs. However, state and local governments have been struggling with fiscal crises for the last fifty years; employment in these levels of government is lower today than it was in 2008, despite population growth. These offices simply do not have the staff needed to create and oversee millions of new nonessential jobs. Even if the federal government were willing and able to fund additional capacity, it would take years to set up the staffing required to run such a program.

If the administrative capacity were created, it would still be unclear what those jobs might be. Proponents often point to unmet social needs—such as care for children, the poor, the disabled, and the elderly—as well as environmental protection. These needs are certainly pressing, but they should not be met by a cast of temporary workers who might soon return to private employment. Would the staff-to-client ratio in child-care centers and nursing homes fluctuate with the demand for labor in the private sector?

Finally, there is the question of how to manage the contraction of

public-sector jobs when private demand for labor starts to increase. Would the number of people on the public rolls simply be reduced from month to month, or would public-sector managers wait for individuals to find higher paying private-sector jobs? In the first case, what rule would be used to determine the order in which people would be laid off?

Ideological Problems

Theorists of social change have argued that movements should fight for reforms that have the potential to mobilize people to demand further reforms. There are two aspects to this potential: the first is whether the initial reform empowers people to push further demands, and the second is whether the initial reform challenges the ideology that legitimates the injustices of the existing order. While the federal job guarantee might pass the first test, it does not pass the second.

If a job guarantee were implemented and the labor market became substantially and continuously tighter, the power of working people relative to managers would increase. Union campaigns would have better chances of succeeding, since employees would have less fear of unemployment. Additionally, the tighter labor market would likely make it easier to forge coalitions among workers across ethnic and racial lines.

However, a job guarantee does not challenge the dominant ideas that underpin the vast income and wealth inequality in our economy. The concept of a job guarantee conforms to the biblical injunction “that any would not work, neither should he eat.” A job guarantee does not defy the deeply rooted assumption that the unemployed are responsible for their own failure to find work and are thus undeserving of any support.

Market society rests on the idea that labor is a commodity, like steel or wheat, whose price is determined through the interplay of supply and demand. A job guarantee does not upend this idea; rather, it asserts that the government has a responsibility to assure that supply and demand for the labor commodity are balanced by acting as the employer of last resort.

Some claim that the job guarantee decommodifies work because, once implemented, employment would not depend on profitability and working people would be protected from unemployment. But as Gøsta Esping-Andersen argues in his classic study The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, decommodification concerns the income that people can command when they are not working. Accordingly, he examines the relative generosity of unemployment insurance, pensions, and sickness benefits to assess the extent to which labor has been decommodified. In other words, decommodification is achieved when workers are protected from the pressures to earn a paycheck, not when their paycheck is guaranteed.

Human beings should not be treated like bushels of wheat or tons of steel. Seeing workers as commodities allows both governments and employers to deny that human beings depend on complex networks of caregiving both for themselves and for subsequent generations. The denial of this reality is the foundation for the systematic underfunding of care services for everyone, from infancy to old age.

At the same time, the insistence that labor is just another commodity undergirds the largely unconstrained authority of managers in the workplace. Commodities do not have a voice in how workplaces are run. The prevailing legal rule that employees can be fired on arbitrary or capricious grounds is rooted in this belief that labor is just another commodity. The fight for a government job guarantee does not help make the case that private-sector workplaces should be democratized, or that people like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos accumulating hundreds of billions of dollars is unjust.

Political Problems

Both at the end of the Second World War and in the late 1970s, a broad political alliance mobilized for a federal job guarantee and ultimately won nothing more than rhetorical concessions—despite the labor movement being much stronger then than it is today. The demand unified and mobilized the business class. Virtually every business, from the smallest to the largest, opposes the idea of the government guaranteeing a job for everyone who is out of work. Business owners believe that a job guarantee would shrink the pool of people who apply for job openings, making it harder to fill vacant positions; weaken managerial authority, because employees would have less fear of losing their jobs; produce inflation from an overtight labor market; and necessitate higher taxes to finance it.

In this way, the job guarantee differs from other reformist demands that create divisions in the business community. Many larger firms, for example, tend to sit out battles over raising the minimum wage, since many of their employees already earn more than the minimum. Additionally, a higher minimum wage might result in more customers who can afford their products and reduce the threat of losing market share to firms that compete by paying the lowest possible wages. Some firms also tend to gain from the expansion of government benefit programs. Farmers, for example, have historically supported the food stamp program, because it increases demand for agricultural products. The nursing home industry lobbies to protect Medicaid funding, since the program covers costs for close to 60 percent of nursing home residents.

Whenever possible, it is more strategic to fight for demands that divide the business class rather than those that unify and mobilize it. This recognition is, perhaps, the reason that the demand for government job guarantees is considerably less popular on the left in Europe today than it is in the United States. Unions and left parties in Europe have the same interest as their U.S. counterparts in tightening the labor market, but they have employed strategies that do not produce such intense business resistance. They have, for example, won pension policies that are considerably more generous than Social Security, which allow individuals to receive the maximum benefit at an earlier age.

Many European nations have also embraced active labor market policies that require considerable funds to retrain displaced workers. Such programs can gain significant business support because they reduce costs for industries that need employees with particular skills. In 2021, the United States spent 0.04 percent of its GDP on such policies. France and Germany, in contrast, each spent more than ten times that level, while Ireland, New Zealand, and the Netherlands each spent more than 1 percent of GDP.

If the U.S. actors who fought unsuccessfully for the job guarantee in the 1940s and 1970s had devoted their efforts to other demands, they could likely have won significant concessions that would have tightened the labor market. Instead, on two separate occasions, they spent a huge amount of political capital to receive next to nothing.

To be fair, the campaign in the 1970s did produce a small material concession: CETA, which, as noted earlier, employed 750,000 people in 1978. However, bad publicity about the highly decentralized program’s lax management practices eroded congressional support for the effort, and it was soon terminated by the Reagan administration. Poor implementation of the job guarantee could kill it quickly, even after it becomes law.

Alternatives

None of the drawbacks of a federal job guarantee invalidate the goal of building working-class power through full employment. But the flaws of a federal job guarantee suggest that we need to pursue other means to accomplish this goal.

In a number of European countries, public-sector employment represents more than 25 percent of total employment, while public employment in the United States makes up only about 15 percent of total employment. Increasing public employment in the United States to just 20 percent would yield 8 million new jobs—more than the 7.2 million unemployed as of July 2024.

Local and state governments have been hollowed out by decades of fiscal crisis; if the federal government shared billions of dollars of tax revenue with state and local governments, the labor market would tighten. This is not a utopian demand: such a program was in place in the United States between 1972 and 1986. The amount transferred each year was less than $10 billion, but with additional tax revenues, hundreds of billions could be redistributed. With a new revenue-sharing program, state and local governments could increase permanent employment for librarians, teachers, construction workers, and maintenance workers.

Revenue sharing could also expand federal support for the care economy, from child care to programs for the elderly. Such spending is urgently needed, since care jobs tend to be poorly paid and care facilities are typically understaffed, resulting in low-quality care. Funding for this purpose was included in early versions of the Build Back Better legislation in 2022 but did not survive debates in the Senate. This funding could further tighten the labor market by creating millions of well-paying care jobs.

Other expedients include significant expansion of government-funded job training programs that develop real skills. Additionally, existing employment could be more broadly shared by shortening the work week and the work year and instituting a sabbatical system that would allow midlife employees to take paid leave for six months. There should also be greater availability of low-cost loans to finance the creation and expansion of small businesses, nonprofits, and cooperatives.

The government could also reduce unemployment during economic downturns by emulating a German program that uses unemployment funds to compensate for shorter work hours. Under this program, a factory worker’s hours would be cut by 30 percent, for example, but the government payment would reduce the worker’s income by only 10 percent. This mechanism allowed Germany to avoid mass unemployment during the global financial crisis.

In addition, the federal government could create a permanent civilian conservation corps that would provide two-year jobs to improve national parks and build climate resilience, in cooperation with state and local governments. During economic downturns, this effort could be ramped up to employ more people. Similarly, the capacity of job training programs could also be increased when unemployment rises.

These other strategies for tightening the labor market will face stiff resistance from conservatives and much of the business community. But they all have the great advantage that partial victories can be won. The federal job guarantee, in contrast, is functionally an all-or-nothing proposition. In the fight for these other demands, it would be possible to win concessions that make a real difference in people’s lives and create a foundation for further struggles. Moreover, revenue sharing for state and local governments, as well as central government support for care services, challenge the idea of market justice by insisting that the government must meet some of people’s needs.

The job guarantee holds an important place in the history of the left. But we don’t need to continue repeating the demand for national workshops to put the unemployed to work 176 years after revolutionary French workers proposed the idea. A durably tight labor market is an important goal, but it is an illusion to believe that a government job guarantee is an effective short cut to achieve that end.

Fred Block’s newest book, The Habitation Society: Creating Sustainable Prosperity, will be published in December 2024.