The Left Needs Bureaucrats

The Left Needs Bureaucrats

After MAGA, the left will need to be ready with a theory of how to rebuild the federal administrative state—not as it was before Trump, but as something better.

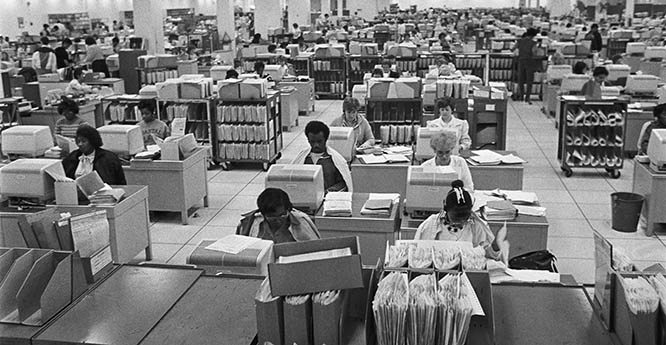

With Zohran Mamdani’s ascent to Gracie Mansion, a democratic socialist is now chief executive for the largest municipal bureaucracy in the United States, meaning that he oversees the daily activities of roughly 300,000 employees. Most of these employees are what the political scientist Michael Lipsky called “street-level bureaucrats”: the teachers, firefighters, cops, bus drivers, and others whose jobs put them into direct and regular contact with civilians. But they also include the urban planners, economists, analysts, and administrators who operate behind the scenes and at the higher echelons of city government: the people who help write the city’s budget, study traffic patterns, and run grant and incentive programs.

It is this latter category of civil servants that will be tasked with turning the cumbersome machinery of city government in the direction indicated by Mamdani and his political appointees. Implementing a sewer socialist agenda in New York City will be, to a great extent, an enormously complicated technical exercise, carried out by a small army of trained technicians.

It is difficult to predict how well Mamdani will perform as an administrator. One reason to be hopeful is that he’s surrounded himself with people who have more experience than him at managing large bureaucracies. His transition co-chairs included Biden’s Federal Trade Commission chair, Lina Khan, and three former deputy mayors. During the campaign, he made a point of soliciting advice from seasoned public servants like former New York transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan (no relation to Lina) and former sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia.

In another positive sign, Mamdani appears to have inspired a horde of supporters to join the civil service. Two days after the election, his transition team launched a portal to solicit applications for city jobs; within twenty-four hours, they reported that they had received 25,000 résumés.

That’s good news for New York City, but it’s also good for the left—not only because much of democratic socialism’s national credibility now hinges on Mamdani’s performance as mayor, but also because his example, and the example of supporters who follow him into public service, might help to liberate the American left from one of its more pernicious—and tenacious—intellectual tendencies.

In his recent book Why Nothing Works, Marc Dunkelman refers to this tendency as “Jeffersonian progressivism,” or a preference for “pushing power down and out” over the more “Hamiltonian” strategy of building strong, centralized institutions to serve progressive goals. The Jeffersonian-versus-Hamiltonian dichotomy is a little too schematic, but it does gesture toward a real tension within the American left. On the one hand, the left needs a muscular state—capable of overseeing large-scale infrastructure projects and redistributive programs—to realize its vision. On the other hand, there exists a strain of leftist thought that is inclined to reject anything that smacks of hierarchy, centralization, formal rules, and decisions made through any process other than consensus. Some leftists find themselves negotiating an uneasy compromise between these twin imperatives; others embrace one or the other.

Mamdani and some other high-profile figures of the socialist left, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have shown a pronounced interest in the uses of state power and public administration. But the left’s anti-bureaucratic wing, influenced by C. Wright Mills, Students for a Democratic Society, and other pillars of the New Left, remains alive and well.

Since the beginning of Trump’s second term, the right’s own anti-bureaucratic forces have been on a rampage through the federal government. The worst came during the brief life of Elon Musk’s semi-official Department of Government Efficiency. In February 2025, Musk—who was, at the time, a sort of shadow U.S. president—announced that federal employees would need to write an email explaining what they had gotten done over the previous week or face summary dismissal. The subtext was Musk’s belief that most of the federal civil service did nothing on a weekly basis; an earlier DOGE email had encouraged civil servants to move “from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.” (This is not to say that Musk views all private sector jobs as intrinsically productive; prior to joining the Trump administration, he claimed to have eliminated 80 percent of the staff at Twitter/X using similar tactics.)

Though Musk likely doesn’t realize this, his own anti-bureaucratic politics contain some New Left DNA. The relationship between the New Left and what would eventually become the tech oligarchy’s particular flavor of reactionary modernism was first explored in “The Californian Ideology,” Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s 1995 essay about “a bizarre mish-mash of hippie anarchism and economic liberalism beefed up with lots of technological determinism.” Barbrook and Cameron understood the predominant culture of the emerging Silicon Valley tech industry to be a cross-ideological fusion between the New Left’s anti-establishment, countercultural leanings and the right’s worship of industrial titans. The glue holding these elements together was a sort of neo-Jeffersonianism. And like Thomas Jefferson himself, the heroes of the Californian Ideology were shadowed by their own bad faith: they propounded an anti-hierarchical, anti-statist worldview even as they profited from both access to state power and their own lofty status within the prevailing racial and economic hierarchies.

DOGE represented a breakthrough for the rightmost version of the Californian Ideology—one that the left has fought at every turn. But while the left has opposed DOGE and the Trump administration’s other attempts to strip-mine the administrative state, it has been more reluctant to reckon with the lingering influence of the New Left on its own attitude toward state power. It is not enough for the left to play defense against the right’s attacks on civil administration; the left must also follow Mamdani’s lead in embracing the power of bureaucracy.

The poverty of anti-bureaucratic politics was on full display during a 2014 conversation between two of its most influential modern advocates, on both the left and the right. Peter Thiel, another avatar of the Californian Ideology and one of the most tireless popularizers of Silicon Valley fascism, participated in a public “debate” with David Graeber, the anthropologist and public intellectual who was the left’s most prominent bureaucracy skeptic until his death in 2020. The subject of the debate, which was hosted by The Baffler, was “Where Did the Future Go?” Graeber and Thiel were united in their belief that bureaucracy killed it; as Thiel said early on, “There’s a disturbing amount I actually agree with David on here.” Through their common intellectual forebears on the New Left, Thiel’s fascism is something of a distant cousin to Graeber’s anarchism. That shared intellectual lineage may help to explain the remarkably chummy tenor of the conversation.

Graeber and Thiel diverged in their prescriptions more than their diagnosis. As Graeber told Thiel, we ought to see American democracy for what it is: “a system of organized bribery and little more.” As one of the architects of Occupy Wall Street, Graeber held to his conviction that people should self-organize into democratic structures, and then use those structures to accomplish their goals outside the suffocating grip of the state. Thiel shared Graeber’s cynicism regarding the American project and agreed on working outside bureaucratic structures to achieve shared goals, but, as a self-described “political atheist,” he dissented on the “democracy” part.

In an essay republished in The Utopia of Rules, a 2015 collection pitched against the very idea of bureaucracy, Graeber wrote that it was “becoming increasingly clear that in order to really start setting up domes on Mars . . . we’re going to have to figure out a different economic system entirely,” because bureaucratic neoliberalism was unlikely to get us there. Thiel cited this passage as his point of divergence from Graeber. “I would say, in order to get cities on Mars with domes . . . we need to start working on going to Mars.” He noted that his former PayPal colleague, a man named Elon Musk, was doing just that: he had formed a company, SpaceX, that would work toward the colonization of Mars. He hadn’t waited for a revolution; he had just done it.

In his reply, Graeber never makes the case that SpaceX won’t be able to reach Mars, only that a democratically organized society is the more appealing mechanism for getting there. But why wait around for a democratic society if undemocratic (or even antidemocratic) firms are planning trips there right now? If you’re an ambitious young engineer who believes reaching Mars in the foreseeable future is more important than doing it as part of a horizontalist affinity group, what does Graeber’s vision have to offer you that Thiel’s does not?

Watching the debate can be a chilling experience, because Thiel has the stronger argument. At one point Graeber casually notes that he doesn’t “think that creating very large scale, but fundamentally democratic structures, historically, is that hard.” But he doesn’t provide any examples, and we can safely assume that he doesn’t believe any of what we call the modern world’s advanced representative democracies count. So what you’re left with is a vision far too airy and insubstantial to withstand a barrage from Thiel’s actually existing rockets.

Fortunately, there is a real-world alternative to SpaceX that we can point to. It’s called NASA. It’s a public sector bureaucratic organization that has already sent multiple manned missions to the moon. A left that views getting to Mars as an important goal should embrace the democratically controlled state—not an anarchist collective or private fiefdom—as our best mechanism for reaching the stars and ensuring that the benefits of space exploration are broadly shared. (It’s worth noting that Graeber acknowledges the existence of NASA in his discussion with Thiel, but argues that its best days are behind it due to “a shift in the nature of bureaucracy that happened in the ’70s.”)

Whether you think we should set up cities on Mars or not, the persistence of New Left anti-bureaucratic thinking acts as a self-imposed check on the left’s more earthbound aspirations. Graeber best articulated his antipathy to state-building in The Utopia of Rules:

The social movements of the sixties were, on the whole, left-wing in inspiration, but they were also rebellions against . . . the bureaucratic mindset, against the soul-destroying conformity of the postwar welfare states. In the face of the gray functionaries of both state-capitalist and state-socialist regimes, sixties rebels stood for individual expression and spontaneous conviviality, and against (“rules and regulations, who needs them?”) every form of social control.

“Rules and regulations, who needs them?” is a line from a Graham Nash song about the protests surrounding the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago—a seminal moment in the history of the New Left.

In his 2018 book Bullshit Jobs, Graeber continued his attack on the “bureaucratic mindset” by arguing that pretty much all administrative and managerial work is, well, bullshit. His targets included “useless bureaucrats,” lobbyists, and think tank employees, who he compared to “the endless accretion of paid flunkies and yes-men that inevitably assemble around [people who do a great deal of harm in the world] to come up with reasons why they are really doing good.” No doubt he considered eligibility verification specialists at the Department of Social Services, data analysts at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and public records officers at the Department of City Planning—as I write this, New York City is hiring for all three positions—to be working bullshit jobs. But those jobs do matter, and it matters who does them, too. An eligibility verification specialist might be the person who determines whether or not a housing insecure family receives rental assistance; for that family, the difference between stable housing and homelessness might come down to whether the specialist in question is committed to helping them prove their eligibility.

It’s easy to see the problems with Graeber’s dismissal of bureaucracy from our vantage point. We are seeing in real time what happens when someone takes a sledgehammer to the institutions that can, however imperfectly, provide some small measure of economic security to households that would otherwise be utterly destitute. There have been many noble attempts to defend the bureaucracy we do have; the Federal Unionists Network, a coalition of unionized federal employees, has done essential work in that regard. FUN has organized protests against DOGE cuts, provided trainings on how to resist the depredations of the Trump administration from within the federal bureaucracy, and pressed congressional Democrats to take a firmer stand against Trump.

But preservation alone cannot be the goal. At its best, government bureaucracy can be an instrument for leveling inequality and extending what Franklin D. Roosevelt called “freedom from want” to millions. The work of making freedom from want into a guarantee for everyone is still unfinished.

Instead of retreating into facile cynicism about the safety net and regulatory state, people on the left should be trying to occupy the bureaucracy at the state, local, and, after the MAGA putschists are finally expelled from power, federal level—not simply because we need good people in those jobs, but because enough good people in any given department can change its internal culture for the better. A lot depends, for example, on whether state and local transportation departments are staffed by car-brained traffic engineers or planners who are genuinely invested in walkability and developing viable mass transit networks. Just as much hinges on whether state health agencies are staffed by people with a genuine commitment to the cause of universal healthcare, even in the face of brutal federal Medicaid cuts.

There’s another reason for occupying the bureaucracy, too. For a movement that wants to transform the state, there is tremendous value in understanding how policy implementation and institutional change happens on a granular level. If you spend some time working inside the bureaucracy and you keep your eyes open, you can learn a lot about the points of leverage that leftist politicians and outside advocacy groups can press to their advantage. On the flipside, you can also learn a great deal about the tradeoffs associated with certain approaches and how well-intentioned but undercooked policy initiatives can produce unintended consequences. These are all important lessons for anyone trying to push any level of government in a more humane direction. But they’re especially important lessons for leftist officials who have ambitious agendas, a finite amount of time in which to implement them, and little room for error.

Zohran Mamdani is, of course, one of those leftist officials. The left has gained a degree of power over New York City. Mamdani and other socialist officeholders will have to figure out how to wield that power effectively. And when the post-Trump era finally arrives, the left will also need to be ready with a theory of how to rebuild the federal administrative state—not as it was before Trump, but as something better. To do either, the left needs bureaucrats.

Ned Resnikoff is an independent writer and urban policy analyst. He is currently a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute and working on a book with an expected publication date of fall 2026.