The Geopolitics of Industrial Policy

The Geopolitics of Industrial Policy

Is a new Cold War the price of admission for the return of industrial policy?

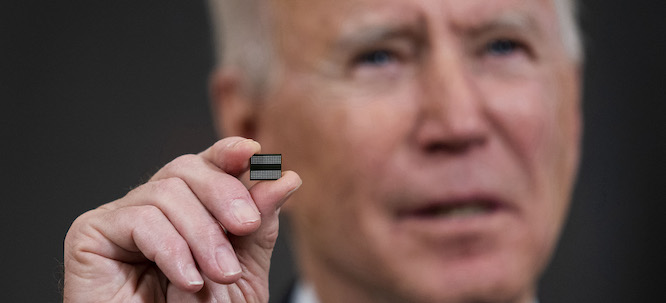

It has become clear that old assumptions about globalization no longer apply. The idea that goods should be produced and services should be offered wherever the costs are lowest without regard for distributive effects has lost the status of common sense. After the Trump administration broke with the free trade consensus, the Biden administration followed suit. Many on the left have been invigorated by this opening, seeing the possibility of post-neoliberalism in the renewed attention to the long-neglected political aspects of political economy. However, this shift has happened alongside a growing bellicosity of the United States—toward China in particular.

Is a new Cold War the price of admission for the return of industrial policy? Can we develop a new political economy without placing national security on the throne once occupied by market competitiveness? Can military escalation be used tactically in the interest of a just energy transition, or is that a fool’s wager? We assembled a panel of experts to discuss these questions—with some slightly surprising conclusions.

—Thea Riofrancos and Quinn Slobodian

Thea Riofrancos: We’ve already had a few years of debate over Bidenomics—or what National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan recently dubbed the new Washington Consensus—and parallel developments in the European Union. A lot of this debate has focused on the question of rupture vs. continuity: is this just more of the same neoliberalism with a slightly different face, or is this a fundamental break—or a return to some industrial policy past?

We are focusing here on a different question, about geopolitics, especially conflict between the United States and China: is national security and the new Cold War the reason why we’re seeing a policy shift, insofar as we are seeing one?

Yakov Feygin: The China factor is not new. The Trans-Pacific Partnership was in large part motivated by Chinese-U.S. economic relations—and that was a free trade bill. The pressures are the same, but the responses clearly look different.

I think there are three reasons why we shifted from a TPP framework to an investment policy framework. One is evidenced by the failure of an earlier piece of American climate legislation, the Waxman–Markey Bill, in 2009. To do climate policy in America, you need to have all the parts of the Democratic coalition on board, and labor was not on board. Unions are willing to work with legislators on industrial policy, however, and that’s why we were able to get the Inflation Reduction Act. It took a lot of work to get the United Mine Workers to pressure Joe Manchin to play ball.

A second reason is the Trump win, which made it impossible not to talk about the preferences of Midwestern, deindustrialized voters. Polling shows that the... Subscribe now to read the full article

Online Only

Print + Online

Already a subscriber? Log in: