Sins of Omission

Sins of Omission

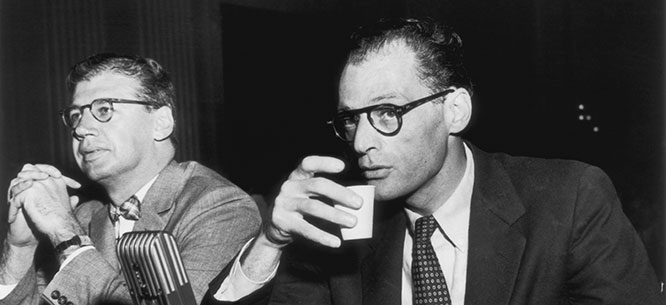

Arthur Miller’s landmark play The Crucible illuminates the difference between informing and truth-telling.

John Proctor Jr., a Puritan settler of Salem Village, Massachusetts Bay Colony, was convicted of witchcraft in a Salem court on August 5, 1692, and hanged two weeks later. He was one of twenty men and women executed in the Salem witchcraft trials.

Roughly two and a half centuries later, a character named for and loosely based on Proctor appeared as the protagonist of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, which opened on Broadway on January 22, 1953. As New York Times drama critic Brooks Atkinson noted in a dry understatement in his review of the play, “Neither Mr. Miller nor his audiences are unaware of certain similarities between the perversions of justice then and today.”

The Crucible would become Miller’s most frequently performed work. But its reception in 1953 was mixed, although it won a Tony Award for Best New Play of 1953.

A week after his initial review, Atkinson devoted a column in the Times to some second thoughts on the parallels implied in The Crucible between the “perversions of justice” in seventeenth-century Salem and mid-twentieth-century America. While there “never were any witches,” Atkinson now felt compelled to point out, “there have been spies and traitors in recent days. All the Salem witches were victims of public fear. Beginning with [Alger] Hiss, some of the people accused of treason and disloyalty today have been guilty.”

Atkinson had been an outspoken critic of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and Senator Joseph McCarthy. That he felt obliged, in effect, to review Miller’s play a second time, and more critically than the first, is revealing of the political pressures and complexities of American anticommunism in the McCarthy era. American Communists were being victimized in those years in ways that, like the Salem trials, and more recently the Red Scare of 1919–20, represented a cruel miscarriage of justice. At the same time, Communists were not without their own sins. Charges of “espionage” in the 1940s and 1950s were not always instances of malicious hyperbole.

The “McCarthy era” of American politics, known for the hurling of reckless partisan accusations of Communist subversion, is somewhat misnamed, since the junior U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, only became associated with the issue when he charged, in a highly publicized speech to a Republican gathering in February 1950, that scores of U.S. State Department personnel were card-carrying members of the Communist Party. By then, the post–Second World War Red Scare was nearing the half-decade mark. It was an era of mass hysteria and official repression that wrecked lives and careers and tarnished American democratic ideals in the name of defending them. It also would outlive its namesake, who died in 1957.

On June 19, 1953, the night that convicted atomic spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg died in the electric chair, The Crucible was nearing the end of its Broadway run. When John Proctor was executed offstage in the culminating moment of the final act, the audience rose and stood in silence, in a heartfelt demonstration of solidarity with the Rosenbergs, who they believed were simply victims of injustice. (The audience was mistaken, at least in regard to Julius Rosenberg—who was indeed a Soviet spy during the Second World War.)

Christian tradition distinguishes between sins of commission—overt violations of Scriptural commandments—and sins of omission—a failure to do that which is required of the righteous, even when no commandment has been broken. While revelations of Americans spying for the Soviet Union dominated headlines in the McCarthy era, only a handful of Communists were guilty of such sins of commission. Most of the laws that Communists were accused in court of violating involved expressions of opinion, which should have been protected under the Bill of Rights. In retrospect, the party’s abiding sins involved the second category, sins of omission: the collective failure by Communists to speak truthfully to others and, fatefully, to themselves.

The movement to which they devoted their lives was based on lies—not about everything, but certainly in regard to one central issue, the nature of the Soviet Union. Daily Worker editor John Gates noted in a 1958 memoir that he and his fellow Communists had “never mastered the art of persuading very large numbers of Americans, deceptively or otherwise.” Instead, Gates suggested, the one deception they excelled at was self-deception, “the basic cause of [our] demise as an effective political trend.”

Arthur Miller, born in New York City to Jewish parents in 1915, grew up in privileged circumstances, living in an apartment with a view of Central Park, until his family’s fortune was wiped out by the Great Depression. The Millers then moved to a modest neighborhood in Brooklyn, and after finishing high school Arthur delayed attending college for two years due to tight finances. Finally, in 1934 Miller enrolled at the University of Michigan. As a student journalist, he was drawn to the left, covering the Flint sit-down strike of 1936–37 for the campus newspaper.

After graduating, Miller returned home to Brooklyn and perfected his craft as a playwright. During the early 1940s, he attended Communist-sponsored meetings in New York and wrote theater reviews for the New Masses under a pseudonym. He was a prominent supporter of Henry Wallace and the Soviet-aligned Progressive Party in the 1948 presidential election. Despite all this, it seems that he never formally joined the party.

Miller secured his reputation as the foremost American playwright with the Broadway successes of All My Sons in 1947 and Death of a Salesman in 1949. The latter won him the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Given his political past, Miller would have almost certainly drawn the hostile attention of anticommunist witch hunters sooner or later. His authorship of The Crucible guaranteed it. Miller had wanted to write a play about the Salem trials since his college days, with loyalty and betrayal a recurring theme in many of his works. The HUAC hearings of the late 1940s and the Smith Act trial of Communist leaders in 1949 inspired him to turn to the project again.

Broadway theater proved relatively immune to the anticommunist pressures that ended the employment of scores of left-leaning Hollywood directors, screenwriters, and actors in those years, so Miller continued to see his plays performed. However, he spent the next few years embroiled in the legal consequences of writing The Crucible, starting with the revoking of his passport by the State Department. In 1956 he was dragged before HUAC and asked why the Communists applauded his Salem play. And, of course, he was asked to name names. But he refused to do so, citing both the First Amendment protections of free speech and his own personal sense of right and wrong. “I want you to understand I am not protecting Communists or the Communist Party,” he told his inquisitors. “I am trying to and I will protect my sense of myself. I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble to him.”

Miller’s pessimistic view of humankind may have been one of the reasons he never joined the Communist Party. In a biography of Miller, John Lahr wrote that in The Crucible John Proctor “is the messenger of disenchantment, embracing complexity, ambiguity and guilt.” From the play’s opening act, the audience knows Proctor had an illicit relationship with Abigail Williams, a young woman formerly a servant in his house, who helped ignite the hysteria about witchcraft. Proctor finally confesses his adultery. He is guilty, just not of the crime of which he is accused.

In Miller’s stage directions for The Crucible, Proctor is described as “a sinner not only against the moral fashion of his time, but against his own vision.” His is a sin of both commission (adultery) and omission (dishonesty). The sin he will refuse to commit is to falsely accuse others of consorting with the Devil, even though to do so would save his life. Why not make the accusation? his puzzled interrogator asks. After all, the individuals he is being asked to denounce have already been named as witches by “a score of people.” “Then it is proved,” Miller has Proctor reply. “Why must I say it?”

Truth-telling and informing are two very different things. For the purpose of Miller’s play, Proctor’s confession to his real sin of adultery redeemed him morally, even if it did not spare him the hangman’s noose. Like Proctor, American Communists had their own sins to confess—just not, for the most part, those they were being accused of before official tribunals. “Complexity, ambiguity, and guilt” are not absent from the history of American Communism. As the worst of McCarthyism was coming to an end in the later 1950s, American Communists like John Gates became willing, at long last, to speak their own sins.

Excerpted from Reds: The Tragedy of American Communism by Maurice Isserman. Copyright © 2024. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Maurice Isserman, the Publius Virgilius Rogers Professor of History at Hamilton College, is the author of a number of histories of American radicalism, including If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (1987), which includes a chapter on the early history of Dissent. He has been a frequent contributor to Dissent in the years since then.