Mr. Lonely

Mr. Lonely

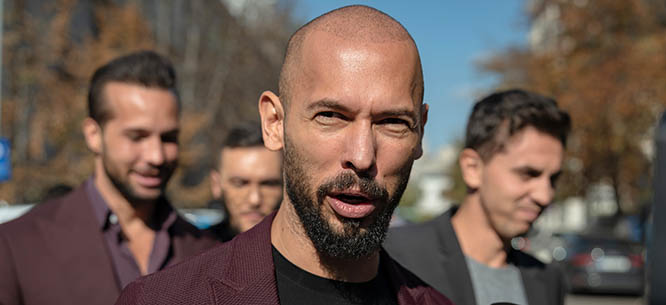

Some have suggested that young men are drawn to Andrew Tate because they suffer from a dearth of social contact. Yet men go to Tate not to alleviate loneliness but to intensify it.

When asked in 2023 what “men want in women,” the notorious influencer, professional kickboxer, and accused human trafficker Andrew Tate gave a predictable answer: “No one’s going to respect the man who’s with an ultra-promiscuous woman. No one is going to respect the man who’s with a woman who is back-talking him or horrible to him in public. No one is going to respect the man who’s with a woman who clearly isn’t interested in him sexually.” What a man wants is the respect of others, which a woman can only convey, vacantly and impersonally, the way an electrode carries a current.

It is this inflamed, anxious kind of notion that has made Tate an inescapable figure of the online right. In his videos and social media posts, Tate has fueled the contemporary anti-feminist backlash by repeating, again and again, its galloping litany of fixations: the defense of male honor and the fear of female sexual freedom and social censure. Andrew Tate knows his script and how to hit its most advantageous beats.

What is striking, however, is that having made his name as an influencer—someone who supposedly knows something about life, or at least lifestyles—Tate can issue only the most timid and uncreative prescriptions for heterosexual romance. According to Tate’s statement, a successful relationship is one in which a woman refrains from cheating on, or being mean to, her partner. It is one where she doesn’t not want to have sex with him. This is a narcissistic, childlike understanding of love: stripped of conflict and, like all juvenile fantasies, either consecrated or menaced by a powerful, imaginary audience.

In Clown World, a recent insider account of his malodorous career as an alt-right celebrity, Tate is constantly performing before audiences. He performs on TikTok, on Fox News, and for the two journalists, Matt Shea and Jamie Tahsin, who tasked themselves with chronicling Tate’s career. Since the 2010s, Tate has pursued power primarily through a series of online gambits, which, with the pandemic as an accelerant, have made him a spokesperson of right-wing hate, anti-vax conspiracies, and raw misogyny. Clown World focuses on Tate’s War Room, a costly, membership-only network of male associates whom Tate trains to “achieve the pinnacle of masculinity and wealth.” As the book shows, the Tate brand is rooted in the American promise that any man can become as heartlessly successful as Tate, so long as they follow—that is, purchase—his teachings. This explains Tate’s popularity, as well as the danger he poses.

Tate is a man who claims he has “never met a woman who will not do the basics of what [he says].” For him, power is a vehicle to admiration, and admiration is at variance with intimacy. To be admired by someone is to forever be at a distance from them, and this is where Tate prefers his women. What men and boys learn from Tate, in other words, is how to optimize a life bereft of love or friendship. In Clown World, Tate declares that men “should never be friends” with their sisters: “When I see a brother and sister who are really close, it’s just weird.” Tate also maintains that he “will never live alone exclusively just with a woman,” because “that’s where men go soft.” Women are accessories that signal status and must be kept out of the house. In this way they are just like sports cars, another Tate obsession.

This blend of machismo and individualism differs greatly from a more old-fashioned sexism in which men denigrate women yet demand their care and companionship. Patriarchy used to position women as natural caretakers and dependents; women were fitted into a domestic sphere in which they played necessary if inferior roles, bartering obedience for security. Tate’s misogyny is much simpler and much lonelier. The fraught bliss of the shared home is missing from the aspirational fixings of Tate’s influencer image. Women and property are viewed simply as financial assets. There is no marriage or romance, however false and abusive, in Tate’s world—just girlfriends who are allowed to stay with him for “extended periods of time.”

Clown World opens as a sociological effort to understand “the itch that Andrew Tate and the War Room have been scratching in young men.” Shea and Tahsin embed themselves in Tate’s milieu, keeping their pointed questions to a minimum; they absorb Tate’s self-mythologizing and meet the strange henchmen in his orbit, who go by names like “the Money Pilot” and “Alpha Wolf.” To earn Tate’s confidence, Shea agrees to participate in “The Test,” a cage match that Tate has arranged with a professional MMA fighter who “has been training for the last eight weeks . . . with the intention of destroying whoever turns up.” (All members of the War Room have the opportunity to take The Test if they can afford the $5,000 fee.) Shea admits that he participates in the fight, which he loses quickly, not just to maintain journalistic access but as a trial for his own wayward masculinity. It seems we are in ill-fated gonzo territory: two white-collar journalists, dallying with the kind of male savagery they’ve left behind but find darkly compelling.

The book takes a turn, however, once Shea leaves the cage. As they begin editing a documentary about the War Room and The Test, the two journalists are contacted by several women who met Tate when he was still an unknown hustler in England. Here the narrative pivots to Tate’s robust history of crime and sexual misconduct, and the book becomes sharper, more dogged. The women we hear from in Clown World dated Tate in 2015 and 2016 and were persuaded to work for a webcam business he owned at the time. Several were sequestered in his apartment and forced to cam for paltry wages; Tate has since bragged about earning “100 percent” of the profit from their sex work.

At least three of the women who knew Tate at the time have since accused him of raping or physically assaulting them. “I don’t give a fuck if you call the police,” Tate reportedly told one after she locked herself in the bathroom. “I’m going to beat the shit out of you.” Against all odds, the women still tried. They filed reports and handed over their phones and medical records. After the police and then the Crown Prosecution Service refused to bring their cases to court, the women repeat their stories—devastatingly, be-latedly—to Shea and Tahsin. Clown World, which documents these women’s accounts in all their overlapping details and horrors, becomes the kind of transparent and robust investigation that the British authorities never completed. As Shea and Tahsin note, the same Crown Prosecution Service that received these women’s claims was exposed in 2019 for throwing out rape cases under the express mandate of improving conviction rates. If the cage fight’s philosophy is one of brute conquest—“might makes right”—Clown World also shows power in its bureaucratic but no less abominable form: organized abandonment, violence meted out as procedure.

We can assume that this early neglect by the authorities allowed Tate to expand his webcam business and eventually propagate it like a bacterial strain. By 2022, Tate is promoting online courses that teach other men how to coerce women into webcamming. His pedagogical offerings include the PhD—Pimpin’ Hoes Degree—which directs students to approach women as sexual conquests before turning them into business opportunities. Find a woman, date her, and then convince her to work for you for miserable pay—or, as Tate unceremoniously puts it, “Inspire a girl to make money and give you the money.” Shea and Tahsin encounter women who have never met Tate but have been abused by his students—a circuit of perpetrators and victims that the journalists conclude is “one of the largest grooming networks in the world.” One woman recalls how, after her boyfriend persuaded her to start producing OnlyFans content for him, he forbade her from keeping “any of the money” and soon “became violent.” Another woman describes her first time meeting a Tate adept she’d been chatting with online: “as soon as we got to the hotel room, he like, shoved me onto my knees and, like, started having sex with me . . . it felt pretty horrible.”

Because Tate and his followers are so violent, and because they are so stupid, one is tempted to liken their misogyny to a caveman’s reflex, a primal loutishness. This would be inaccurate. The Tate ethos is a wholly modern one, for it magnetizes sexual violence toward the absolute aim of economic exploitation. Under Tate’s program, women are transformed into gig workers and subjected to an imperial profit motive. At the same time, their bodies are open to sexual and physical torture. They are instruments of financial valorization and also mute objects for male pleasure and domination; they are both the means and the ends, and the man who presides over them can have his enjoyment both ways—directly, through rape, or indirectly, through money. This doubled harm is not inherent to sex work: the same principle motivates the factory foreman who docks the pay of his female workers before assaulting them in the backroom, or the likes of Harvey Weinstein, for whom becoming a powerful producer involved becoming a sexual predator. Man, here, is at his ideal form when he is boss and rapist, when a woman cannot show him, in public or private, that she is a real person.

Patriarchy teaches men to approach women as sex objects. Capitalism teaches us that the objects surrounding us are inert and barren of any human origin. Tate stalks the tectonic ridge where these underlying worldviews meet: if everyone is a potential possession, sexual sadism is not an irrational outburst but a supplement to, or workplace perk of, business mastery. People can be made to obey edicts and whims because they are not people at all. This fantasy of treating others like so many movable parts motorizes many of the reactionary beliefs whirring inside Tate’s internet, which promotes the most gimmicky and antisocial of sales techniques. Tate’s associates include pickup artists, who teach other men how to dupe women into sex, and hypnotists, who insist that what they’re practicing is actually “neurolinguistic programming.” They see themselves as experts in the trade secrets of seduction, reducing all people to the one simple trick that gains their total compliance. These ploys, which draw on pop theories of human psychology, are vested with a scientific authority whose flip side is occult charm. To cede all complication and unpredictability to the supreme mechanics of cause-and-effect—if I do this, she does that—is to understand science as magic, and the world as lifeless.

On a supra-individual level, Tate’s domains—the market and the algorithmic internet—run on this very faith in automatism. But what works systemically is less assured on an interpersonal level. The belief that you can force anyone to do what you want requires an infant’s confidence in one’s own powers, which perhaps explains why Tate’s associates are so obsessed with the fantastical icons of boyhood—dragons, myths, and martial arts are all part of the War Room’s imagery and rhetoric. In Clown World, we are introduced to Miles Sonkin, one of the War Room’s “top generals” and the moderator-premier of its online chats. (“He never sleeps,” we are told. “He’s online all the time.”) Sonkin, who appears in the War Room’s promotional videos shooting fireballs out of his hands, started out in sales before moving onto pickup artistry. He sincerely believes that he can rearrange the contents of people’s minds, and that women are incorrigibly evil. His agenda is to “take over the world.”

Having diversified into various services and online networks, Tate has developed a superficially sophisticated enterprise in terms of products and reach. That it is sophisticated does not mean that its basic idea is not idiotic. And that it is idiotic does not mean that it is not fearsome. Eighty years ago, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer reminded us that barbarity is not incompatible with modern reason: in Dialectic of Enlightenment, they describe a social order in which man is “in total isolation from all other human beings, who appear . . . only in estranged forms, as enemies or allies, but always as instruments, things.” In other words, Tate is not an amoral aberration of society but the ultimate mutation of its runaway logic. For him, everything—from the people he knows, to his business prospects, to his social media channels—has been streamlined for easy domination. “Seduction, sex & women,” Sonkin declares, are “nothing more than tools to be utilized in order to build a man’s wealth.” In this world, the patriarchal bourgeoisie’s last refuge from market control—the domestic household—has been annihilated, its content evacuated into grids of administration. The most important thing is to “know the rules of the game.”

Adorno and Horkheimer argued that men came to dominate nature and, in the process, succumbed themselves to the “total schematization of men.” Modern man’s stratagems for control always exceed and swallow him; thus Tate, too, is a pawn in the ordered game he has learned. Before his arrest for human trafficking in 2022, Tate’s empire was based less on his own webcam business than on teaching other men how to replicate its model. His online courses promised that wealth and strength were the outcome of methods anyone could perform. It is a rich irony: by advertising his own masculinity as a teachable, and thus sellable, process, Tate has lost his status as special conqueror. He is just another participant in a system that he happens to know better than most, but which surpasses him anyway. The master becomes the mastered.

Having loudly and triumphantly promoted his illegal business practices, thus leaving a public trail of evidence for the authorities, Tate is now awaiting prosecution in Romania on charges of trafficking and rape, as well as civil proceedings in Britain. Yet millions of men still adore him and listen to his teachings. Shea and Tahsin note that, according to some polling, Generation Z may be “the most anti-feminist generation in history.” The attractiveness of Tate’s ideology has been made clear after Donald Trump’s reelection, which will carry into office multiple—and oft-incompatible—streams of misogyny. While J.D. Vance crows his allegiance to more traditional gender roles, Trump’s prospective cabinet is replete with unabashed sexual predators. Trump himself has toured among the same influencers and podcasters who socialize and work with Tate. The president-elect’s new cryptocurrency venture is being steered by Zachary Folkman, a pickup artist who once founded a company called Date Hotter Girls LLC.

Some have suggested that young men are drawn to Tate because they suffer from a “loneliness epidemic.” For what it’s worth, Tate believes this too, having derided women in his videos for not understanding the interpersonal isolation that men experience. Yet it should be said that men go to Tate not to alleviate loneliness but to intensify it, making it synonymous with power. They accept his premise that life pits the strong against the weak, that social antagonism is a universal condition. They forgo mutual recognition or vulnerability within their relationships, which instead are stacked and arranged for maximum value and extractive potential. It is lonely at the top. It is lonely everywhere else.

What should we on the left do about these Disaffected Young Men, these raging crypto-heads and variously pilled trolls, these misogynists orthodox and heterodox? Whether one believes that Tate’s followers are scammers or have themselves suffered a scam of cultish proportions, it is difficult to forgive their hasty defection to hatred. In the post-election debate about contemporary masculinity and the right, some commentators have described Tate’s ideology as a psychological, if not logical, defense for those men whose footing in society has been shaken loose by late capitalism and feminist protest. In short, men drift to Tate and Trump because they have been marginalized by a changing America. They are only protecting themselves.

In this light it is worth remembering that other modes of defense were once the norm. Stuart Hall described the old working-class cultures of Britain as bulwarks against exploitative bourgeois society. This culture, with its values of cooperation, communalism, and self-sacrifice, rose up as “a series of defenses” against a dehumanizing economic order; its everyday solidarity “sustained men and women through the terrors of a period of industrialization.” Raymond Williams, too, noted that working-class solidarity was often a “defensive attitude, the natural mentality of the long siege.” Solidarity functioned like a street barricade—erected in protection but with the effect of binding a community as one.

We should ask why this type of defense no longer feels relevant to Americans, why so many men latch onto a defensive posture that dehumanizes others, delights in brute competition, and glorifies the will of the individual. What new defensive culture can the left muster as an alternative? For if the left can offer men a plausible defense against the destabilizing, isolating forces of capitalism, then men will come closer to accepting positive programs for that system’s overturn. Such a culture must go beyond new podcasts or samplings of online content. Any worthwhile defense will be rooted in personal feeling and social concourse; it will find its affirmation daily—in institutions, in sustained relationships, in what Hall called a “hundred shared habits.”

In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Adorno and Horkheimer wrote that “with society, loneliness produces itself on a wider scale.” We can’t say we were never warned. Today, our enemies are murkier, our shared interests less volubly named. The challenge is massive. All we have to start with is each other—if, indeed, we can see that far.

Zoë Hu is a graduate student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center.