More Than Sewers

More Than Sewers

The pragmatism of the Milwaukee socialists was inseparable from the international world of socialism that they inhabited and helped to shape.

How should we look back at the history of the “sewer socialists” of Milwaukee? This question has taken on renewed urgency following the elections of Seattle’s Katie Wilson and New York City’s Zohran Mamdani, who has said that “the example of sewer socialism is one that I think of often.” Most historians of the left in the United States have regarded Milwaukee’s three socialist mayors as minor historical figures or neglected them altogether. But attention to the city’s history of socialism increased markedly with the rise of Bernie Sanders, himself a former socialist mayor, and even more so following the decision to hold the Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee in August 2020.

Socialists in Milwaukee achieved electoral success that was unmatched in any other U.S. city in the twentieth century. In 1910, Victor Berger, a founder of the Socialist Party of America and the most influential socialist leader in Milwaukee in the early twentieth century, was elected as the first socialist to sit in the U.S. House of Representatives. The same year, Emil Seidel became the first socialist elected as Milwaukee’s mayor. Voted out of office in 1912, he became Eugene Debs’s running mate in the presidential election, in which Socialists won about 6 percent of the national popular vote—their greatest percentage ever. Daniel Hoan, the city’s second socialist mayor, was elected in 1916 and served for twenty-four years before he was voted out of office in 1940. The third socialist to win election to the mayor’s office, Frank Zeidler, served three terms, from 1948 to 1960, when he decided against running for re-election. As historian Joshua Kluever recently reminded us, socialists from Milwaukee and elsewhere in Wisconsin also allied with progressive Republicans to pass laws in the state legislature related to labor, the judicial process, and public utilities in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Socialists in Milwaukee assembled an impressive urban record. In a 2019 Dissent article, Peter Dreier reviewed many of these achievements, which included innovations in basic services—not just sewage treatment but also public health, housing, education, libraries, fire protection, and parks—along with systematic efforts to reduce corruption through the introduction of modern accounting and other methods. “Sewer socialism” emerged as a catchy way to sum up this history. But if used carelessly, the term can distort the history of socialist politics in the city and reproduce false dichotomies that hinder our understanding not just of the past but also the present.

The history of Milwaukee’s socialist mayors has been recounted by John Gurda, Dan Kaufman, and John Nichols, among others. America’s Socialist Experiment, a PBS documentary, was released in 2020, and Milwaukee features in The Big Scary “S” Word, in which I make a brief appearance in an interview filmed in Turner Hall, an important landmark in the city’s socialist history.

I first came to this history in 2003 as a young assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, where I taught a class on the history of socialism with former Mayor Frank Zeidler. I later joined the cadre of people who drove him around the city to appointments and engagements in the final years of his life. (He was a critic of automobiles and never learned how to drive.) I also attended the monthly meetings of the Socialist Party of Wisconsin, which he regularly chaired. After he died in 2006, I joined in efforts to commemorate his contributions to the city alongside my friend, Anita Zeidler, one of Frank’s daughters.

Although the moniker is often applied anachronistically to the entire sweep of socialist electoral success in Milwaukee in the twentieth century, “sewer socialism” has more precise historical origins in bitter struggles over control of the Socialist Party in the early 1930s. One key moment in this wider battle occurred at the Socialist Party’s 1932 national convention in Milwaukee, which included a hotly contested election for national chairman of the party in which Morris Hillquit, the incumbent, defeated Daniel Hoan, the sitting mayor of Milwaukee.

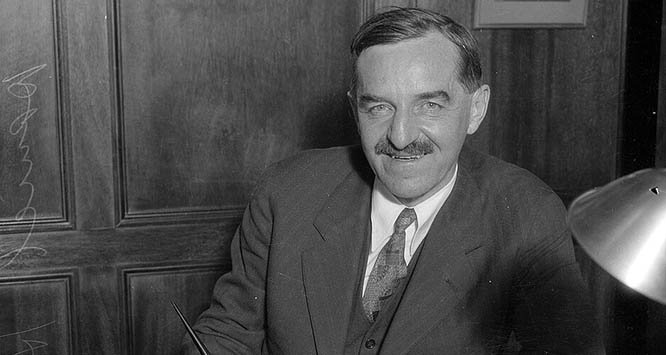

Born Moishe Hillkowitz in Riga in 1869, Hillquit began his political career on New York City’s Lower East Side. A two-time candidate for mayor of New York City, he also ran five times for Congress. A powerful orator and influential party intellectual, he numbered among the most significant Socialist leaders of his time. By 1932, Hillquit was recognized as the leader of the Socialist Party’s “Old Guard.” His opponent, Hoan, was the most important socialist elected official in the United States at the time, but his influence beyond Wisconsin was limited.

In an oft-cited line in his speech accepting his nomination as national chairman, Hillquit proclaimed, “I do not belong to the Daniel Hoan group to whom Socialism consists of merely providing clear sewers of Milwaukee.” What is often omitted from discussions of this line, however, is consideration of another statement by Hillquit at the conference: “I apologize for having been born abroad, being a Jew and living in New York, a very unpopular place.” Of course, Hillquit’s apology was no apology at all, but rather a response to a supporter of Hoan who had implicitly questioned whether he qualified as an “American.” Hoan partisans rejected charges of antisemitism. Milwaukee’s Victor Berger, who was born in what is now Romania, was Jewish. But the acrimony dealt a blow to already faltering efforts to strengthen the party. In this context, Hillquit’s reference to sewers should be seen not just as disdain of Milwaukee socialists’ focus on “immediate results,” but also as a stand against antisemitism and nativism. This fraught history may help to explain why, in the following decades, socialists in Milwaukee rarely used the term to describe themselves. In his Ninety Years of Democratic Socialism: A Brief History of the Socialist Party USA, Zeidler made only one mention of the term, and as a pejorative name applied by outsiders (an “exonym”) rather than a self-description.

Anachronistic use of the term “sewer socialism” flattens the struggles and changes the Socialist Party underwent in Milwaukee. Berger, the key figure in Socialist success in the early twentieth century, rooted his efforts in building an alliance between the party and organized labor. With characteristic hubris, he dubbed this strategy “The Milwaukee Idea,” but the concept borrowed heavily from Social Democrats in Germany. The Socialist press was also critical to the party’s electoral efforts (Berger himself was a newspaper editor). Socialists received support from the city’s large population of German immigrants, although working-class Poles and members of other ethnic groups also played important roles at different points in the city’s history. But there were limits to Socialists’ visions of solidarity that also changed over time. Berger’s racism and enthusiasm for eugenics were noteworthy even in his era. And with only a few exceptions—most notably Meta Berger, Victor’s wife—the party’s leadership consisted of men. Socialists’ base of support in the early 1900s was almost exclusively white and working-class, and mostly non-Catholic; there was a long history of acrimony between the Socialist leadership and the Roman Catholic Church.

The alliance between the party and AFL unions in Milwaukee powered Socialist electoral fortunes into the New Deal era, when it began to fray in the face of competition from the CIO and a new generation who remade Wisconsin’s Democratic Party into the party of labor. Several prominent Socialists joined in this effort, including Daniel Hoan, who ended his life as a Democrat.

By the time Zeidler was elected to his first term as mayor in 1948, the Socialist Party’s influence in Milwaukee was barely an echo of what it had been in the time of Seidel or the early decades of Hoan’s mayoral administration. As historian Tula A. Connell has pointed out, the organization that laid the foundation for Zeidler’s first election was not the Socialist Party but the Municipal Enterprise Committee (later the Public Enterprise Committee), a grassroots coalition of activists who were united not by party membership but by common aspirations. Zeidler continued to be active as a leader in party affairs at both the local and national levels. But in his role as a mayor, he identified as a liberal—a term that, in his usage, included democratic socialists and like-minded people of any party affiliation. Party discipline was an important element of Socialist success in the early twentieth century, when the famed “bundle brigade” canvassed for votes in working-class neighborhoods. But as historian S. Ani Mukherji has pointed out, efforts to maintain discipline were less effective in the Popular Front era.

Zeidler’s success hinged on Milwaukee’s larger associational culture—a rich working-class world sustained by unions and cultural, activist, social, and religious organizations. Eric Fure-Slocum’s study Contesting the Postwar City showed how Socialists played an important role in creating this larger, left-leaning working-class culture, one with origins in the arrival of refugees from the revolutions of 1848 and whose influence can be discerned in Milwaukee even today.

Zeidler celebrated his election as mayor in 1948 in Turner Hall, the seat of the Milwaukee Turners: a multifaceted organization founded by German immigrants in 1853. Turner Hall became a space for forming alliances and personal bonds that drew people together across party lines. The civic infrastructure that Socialists helped to build in Milwaukee sustained Zeidler throughout his political life, as did the company of fellow Socialists, even as they dwindled in number. Zeidler’s political successes before, during, and after his time as mayor owed much to the sorts of organizations and institutions Chris Maisano identifies in his analysis of Mamdani’s victory elsewhere in this magazine.

Today, Socialists in Milwaukee are largely remembered for their achievements within the city’s limits. But they also understood themselves to be international actors, as did a substantial number of the people who voted them into power. Their efforts to remake their city were part of the larger, international networks that Shelton Stromquist has retraced in his magisterial Claiming the City: A Global History of Workers’ Fight for Municipal Socialism. Berger was influenced by his understanding of the Second International and of Germany’s Social Democratic Party, and by his reading of Eduard Bernstein. Other influences on early Socialists included not just Marx and Engels but also Ferdinand Lassalle, the Fabians, Keir Hardie, and Jean Jaurès. Milwaukee’s Garden Homes, a city government-sponsored cooperative, was informed by a study of innovative approaches to workers’ housing in Europe, including England’s Garden Cities.

Milwaukee’s socialists solved problems, it’s true, but the solutions they proposed were inseparable from their ideological commitments, including aspirations for public ownership or, to use a term that Zeidler embraced, “production for use” rather than for profit. Their pragmatism was inseparable from the larger, international world of socialism that they inhabited and helped to shape. The First World War and the Woodrow Wilson administration’s persecution of Debs, Berger, and other radicals were disastrous for the electoral fortunes of the Socialist Party of America in most of the United States. In Milwaukee, however, the party’s opposition to U.S. entry into the war drew support from the city’s substantial German-American population. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 split the left in Milwaukee in ways similar to those in other parts of the United States and fostered tensions within the party and the labor movement. Finally, Zeidler’s efforts to contain the creation of self-governing suburbs in the 1950s through annexation were informed not just by concerns over taxation and infrastructure but also by his efforts to prepare Milwaukee for the possibility of nuclear war on a global scale. His commitment to pursuing world peace through the United Nations was a prominent feature of his politics both during and after his time as mayor. His environmentalism was similarly informed by concerns about the fate of the planet.

Zeidler was the last Socialist mayor elected in Milwaukee in the twentieth century, but his departure from office did not end socialist aspirations in the city, which continue in different forms into the present. The Wisconsin State Assembly has a Socialist Caucus for the first time since 1931. Socialist and socialist-backed candidates have won election to the Common Council, the Milwaukee Public Schools Board of Directors, and the Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors. Today, the Milwaukee Turners lead efforts to defend immigrant rights in the city. Turner Hall has become a popular musical venue while sustaining the Turners’ tradition of gymnastics instruction, which began with the organization’s founding by refugees from Germany’s Revolution of 1848. (Frank Zeidler signed my membership card for the Turners.)

A false notion of socialist pragmatism has emerged in discussions of Mamdani’s goals for New York City and his positions on international issues, particularly around Israel and Palestine. Commentators who are sympathetic to him have stressed that his success will hinge largely on his ability to “deliver” on his ideas for improving New Yorkers’ everyday lives. But those who seek historical analogies to support their case for thinking small should look somewhere other than Milwaukee.

Socialists in Milwaukee built an inspiring record of tackling urban challenges, but their famed “pragmatism” was not an alternative to but rather a manifestation and expression of commitments and ideas that were firmly rooted in their understanding of larger debates within the world of socialism in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In his unpublished autobiography, Emil Seidel gave his own verdict on efforts to relegate Milwaukee socialists to the gutter of history: “Yes, we wanted sewers in the workers’ homes; but we wanted much, oh, so very much more than sewers.”

No doubt Zeidler’s commitment to world peace mattered less to the majority of the voters who elected him to office than it did to his close allies and admirers, Socialist or otherwise. But his internationalism cannot be hived off from his efforts to expand public libraries or increase fire protection in working-class neighborhoods. The same can be said to those who imagine that delivering clean water or public recreation is outside the realm of ideas or ideological struggle. Among the lessons that a newly elected socialist mayor might more accurately glean from Milwaukee would be this: resist any attempt to box in your vision for the city, whether that effort comes from rivals or putative allies. Whatever the future holds for the new mayors of New York City and Seattle, their victories open up new possibilities for us all.

Aims McGuinness is associate professor of history and provost of Merrill College at the University of California, Santa Cruz.