After Marriage Equality, What?

After Marriage Equality, What?

We must tally not only the advantages but also the costs of the LGBT rights movement’s strategic turn to marriage equality.

In the sixty-five-year history of LGBT activism in the United States, the present moment stands out: at no other time would a rational observer of American social movements have called our struggle the one most likely to succeed. Gays were pariahs in the baby-boom era, facing harassment wherever we gathered. The leftist bromide of the post–Second World War decades as a golden age of job security simply didn’t apply to gay Americans. What we today call “discrimination” was the normative condition for any gay person before the liberation era—finding or holding down a good job, with some exceptions, intrinsically required carefully concealing one’s homosexuality. While a few laws prohibiting antigay discrimination by employers and landlords were passed in the 1970s and ’80s, they were difficult to enact and easy to repeal.

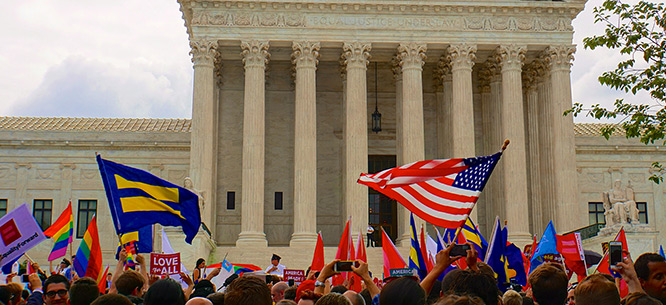

Given our difficult history, the change came faster than anyone expected. After 2003, when the remaining state sodomy laws were struck down and gay marriage was legalized in Massachusetts, our movement flourished as never before, even as those victories produced a crushing backlash. As recently as November 2004, when eleven states passed “defense of marriage” referenda and an antigay president won reelection, the movement seemed to be losing ground. Yet progress continued apace. In 2010 gay Americans were let into the military, and by the time the Supreme Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) two years ago, the movement seemed to nearly everyone to have the wind at its back. This summer, in Obergefell v. Hodges, same-sex couples won rights under family and property law that straight couples have long taken for granted. The plaintiff, Jim Obergefell, who had flown his dying spouse across state lines in a medical jet so they could marry on the tarmac, wanted merely to be listed as such on his husband’s death certificate. More progress looms: in July of this year, the Pentagon indicated that it will allow trans Americans to serve openly in the military by early 2016.

The movement’s next steps will be deeply shaped by the recent strategic turn to marriage equality. As I have argued elsewhere, we must tally not only the advantages of that shift, but also its costs. Yet we must also recognize that the legalization of gay marriage in twenty nations and counting unfolded in ways too diverse to reduce to a simplistic narrative—just as marriage takes many different forms, so has the transition to marriage equality. Though the Netherlands was the first, new democratic governments in Spain and South Africa and the developing nations of Brazil and Argentina made gay couples equal earlier—and in some cases with far less controversy—than the richer nations that followed in their footsteps. Even in liberal France—the only country where civil unions caught on among heterosexuals—marriage equality produced a disturbingly militant backlash, and assisted reproduction for a woman not married to a man remains illegal, with little hope of immediate reform. Ireland this year gave us a spectacle whose sheer moral power is unlikely to be repeated: a nationwide referendum in which a straight Catholic majority set aside church teachings to recognize gay people’s humanity.

Equal treatment was achieved by less inspiring means in England and Wales, where David Cameron rebooted the Conservative Party and modernized its image partly by securing enactment of gay unions in Parliament—while pushing tax breaks for all married couples. Marriage equality is only imaginable today because of earlier feminist struggles to challenge social and legal inequalities between husbands and wives. Yet especially in the United States, part of the urgency driving same-sex couples to demand the right to marry stems from the neoliberal erosion of safety net provisions such as health care and Social Security for the unmarried, and by contrast, the benefits awarded to married couples. Like most hybrid creatures, marriage equality expands our vision of who can marry while also reinforcing marriage as a culturally important and financially consequential rite of passage.

Compared to the extreme cases of England and Ireland—Tory elite opportunism versus triumphant popular democracy—the path of the United States, home to the world’s best-organized gay movement and also its best-organized antigay movement, lay somewhere in between. Here, the path to marriage equality was shaped by federalism, with state-level legislative and judicial twists and turns followed by a justly celebrated high court ruling. The right of interracial couples to marry, affirmed in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia, was more central as legal precedent than anywhere else.

What lies next for the LGBT movement in the United States? The declared next step is securing a federal ban on discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Such measures have limitations, yet they are the bedrock of our civil rights laws. Transgender people, who suffer exceptionally high rates of unemployment and discrimination, particularly need job protections. A divided Equal Employment Opportunity Commission recently ruled that existing sex discrimination laws already prohibit sexual orientation discrimination in workplaces, as they have previously also said of gender identity discrimination. LGBT activists disagree over whether to go to the courts or Congress to codify these rights permanently. For now, it appears likely that a legislative success would require Republicans first losing control of both chambers, as the GOP has shown little sign of “evolving” on basic civil rights issues.

Beyond antidiscrimination laws, there are three key areas to which the LGBT movement must now turn its attention. The first is access to health care. For transgender Americans, access to gender-confirming hormones and surgery is a life-and-death matter, and private insurers have only recently recognized their obligations. While the Affordable Care Act brought major improvements, state Medicaid programs for the incarcerated lag behind. For low-income people living with HIV, President Obama has enacted key steps, but gaps remain. In King v. Burwell, the recent Obamacare case, the legal brief by the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, which pursues civil rights litigation on behalf of LGBT and HIV-positive people, showed that low-income people of color living with HIV in Southern states suffer disproportionately from the refusal of Republican legislatures to expand Medicaid. Lawmakers in both parties continue to block harm reduction programs, especially needle exchanges, even though we know that their moralizing exacts a price in lives.

While the LGBT movement has been on the cutting edge of pushing for more equitably distributed health care in the above areas, however, it has neglected others. For example, since effective treatments made HIV a diagnosis Americans could live with instead of die from, queer activists haven’t challenged drug-company profiteering at home and abroad as much as they once did in the 1980s and ’90s. (Some activists, such as those of Black Lives Matter, on the other hand, have recently opposed antiquated statutes that criminalize HIV transmission.)

Second, the movement ought now to turn to our most vulnerable: the young, the elderly, and other groups—especially transgender women of color—who face poverty and endemic violence. The movement has productively drawn attention to the bullying teens face when they come out while still in school and living with their families. It is less clear whether or how we will tackle the problems senior citizens face. As queer baby boomers retire, many lack children to care for them and/or find that moving to a nursing home means they cannot be as out as safely as before. But the LGBT movement could ally with others in calling for expanding Social Security and other safety-net programs, which would benefit both gay and straight senior citizens.

The third and final policy area to which U.S. activists must attend is the trickiest: LGBT equality abroad. The suffering of so many queer people around the world cries out for international solidarity: as Hillary Clinton rightly said, LGBT rights are human rights. And there are concrete things U.S. policy can do to help. But Clinton also more recently bragged of her “tough conversations with foreign leaders who did not accept that human rights applied to everyone, gay and straight.” Our policy and rhetoric should be calibrated by the fact that we—like Clinton herself—are ourselves latecomers to this cause. LGBT activists should therefore resist such clash-of-civilizations rhetoric, or what queer theorist Jasbir Puar has called “homonationalism”: the use of gay rights as a symbol of our civilizational modernity and superiority. The examples of far-right Dutch and German politicians, who invoke gay rights as a cudgel to demonize Muslim immigrants, point to the dangers that accompany such an arrogant posture.

Let us not be enlisted in militarism and Islamophobia, but rather—as Barack Obama, the gay rights president, said in his second inaugural—in being part of the legacy of “Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall.”

Timothy Stewart-Winter is an assistant professor of history at Rutgers University-Newark and the author of Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics, forthcoming from the University of Pennsylvania Press. His writing has been published in the Journal of American History, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times.

This article is part of Dissent’s special issue of Arguments on the Left. To read more arguments in the issue, click here.