Kashmir Stories

Kashmir Stories

At once Bildungsroman and sprawling history, Malik Sajad’s Munnu tells the story of Kashmir through the eyes of a boy and his violent, insular, emboxed world.

In early February of this year, a trio of students at the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi were arrested for sedition following a panel discussion and protest around the hanging of Afzal Guru. (Guru, a Kashmiri, was convicted for his participation in a 2001 attack on the Indian parliament and executed in 2013.) The question of Guru, who had never met his lawyer, was tortured into confession, and was hung in secret, became a flashpoint for student groups of various political stripes. The students were released within weeks, but not before a sizable protest movement had coalesced around them, linking the question of Kashmiri freedom with the right to protest, freedom of expression, and a wider challenge to student repression and right-wing intimidation under Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s government.

One of the arrestees, student union president Kanhaiya Kumar, has emerged as something of a protest icon since giving an electrifying speech upon his release to eager crowds at JNU. At the core of his appeal was the phrase “Desh mein azaadi”; soon azaadi, or freedom, the mantra of the Kashmiri independence movement, was circling all over India. JNU student Anirban Bhattacharya, also arrested on that day, reminded the audience in a speech a few weeks later on “The Many Meanings of Azaadi” that azaadi refers to freedom from patriarchy and Brahmanism; freedom of speech and intellectual autonomy at the university; but also the unmentionable, freedom for Kashmir. The larger movement that has rallied around these students, a vibrant presence both on campus and beyond, has attracted support from writers, intellectuals, and students around the world, bringing together leftists, secularists, feminists, Dalit activists, and, of course, those sympathetic to Kashmir.

These protests have begun to make visible again a decades-long struggle for justice and self-determination that once captured global attention. While the cause of Kashmiri freedom has been alive ever since the 1947 accession of the princely state of Kashmir to India, it has been more or less politically dead for at least the last decade. Despite three wars (in 1947, 1965, and 1999) and a United Nations Security Council resolution demanding a plebiscite for self-determination (Resolution 47, 1948); despite a full-scale military occupation by one of the largest weapons importers in the world; despite a violent armed insurgency since the late 1980s and the deaths of tens of thousands (reports say 70,000); despite elections rigged by the Indian state in 1987 and a series of massacres by the federal police and border security; despite demonstrations in 1990 by hundreds of thousands in Srinagar demanding the right to plebiscite and another massive wave of protest in 2008; despite consistent nonviolent action calling for independence, or autonomy, or even international oversight, the question of the future of Kashmir has become a non-issue in the world of realpolitik.

The Lahore Declaration—signed by India and Pakistan in February 1999 to affirm their mutual commitment to peace, security, and an urgent resolution of the Kashmir conflict—was followed only months later by the Kargil War, which left some 1,000 dead and brought the two countries to the brink of nuclear war. Restoration of ties the following year never led to any significant demilitarization. Back-channel discussions between Pakistan’s Pervez Musharraf and India’s Manmohan Singh in the mid-2000s, which reached the draft resolution stage, were scuttled by Musharraf’s removal. America’s special envoy to the South Asia region, Richard Holbrooke, had Kashmir effectively taken off his docket by India in 2009. At none of these meetings were Kashmiri political representatives present. At the UN General Assembly in 2010, an Indian delegate reminded the world that “Kashmir is an integral part of India.” For the global community, keeping up relations with the New India has obviated any serious challenge to, or questioning of, that statement. With neither international pressure nor national strategic imperative pushing a resolution to the issue, India’s illiberal hold over Kashmir continues, satisfying the irredentist tendencies of Modi’s party line. Both subsumed under the logic of the war on terror and cordoned off as an “internal” affair, the battle for Kashmir continues largely unwatched by the rest of the world.

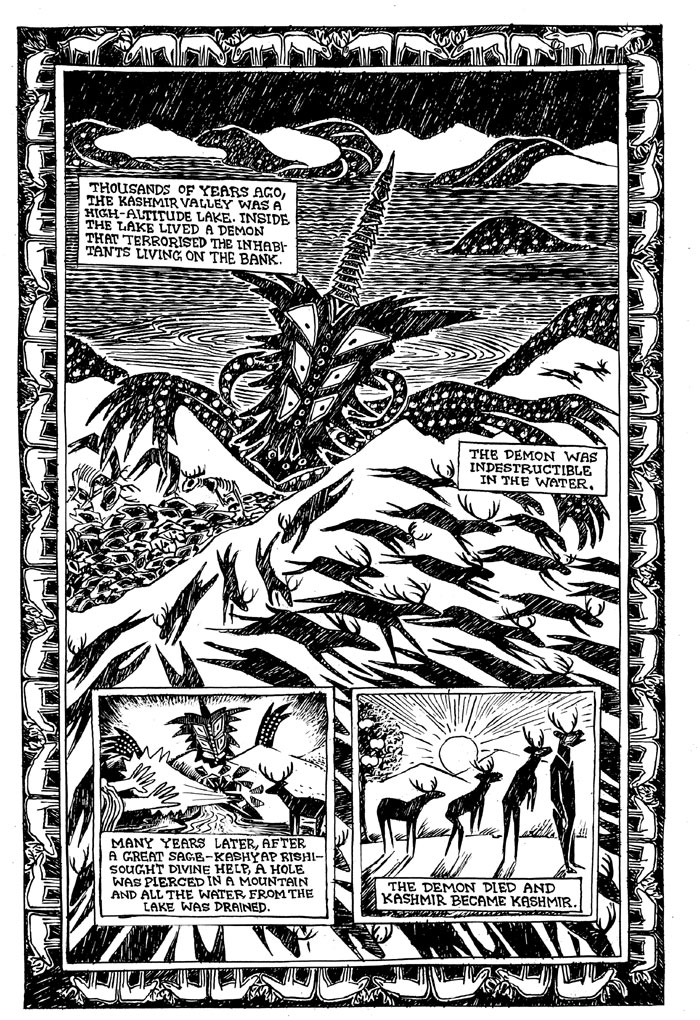

How to fill in the blanks of the “K-word,” that black hole of Indian nationalism? And how might those outside the valley see Kashmir anew? A young artist has recently given us one answer. In Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir, life in the valley is etched into black-and-white cartoon boxes, and Kashmiris—reimagined as hangul, an endangered species of deer native to the region—fill the pages. Munnu is the graphic-novel debut of Malik Sajad, now twenty-nine, who began publishing cartoons in the English-language daily Greater Kashmir at the age of thirteen. It is the story of a young boy in Srinagar—Batamaloo, specifically, the neighborhood that has been referred to as the Gaza of Kashmir—and his family, his schooling, and his entry into the profession of journalism and cartooning. But it is also a story of political education, spanning from the fiery early 1990s to the relatively placid 2010s, as Munnu learns what it means to be a subject in Indian-occupied Kashmir. What it means is the routinization of curfew, the mandatory reporting of adult males to the police for security checks, months upon months of school closures, and the loss of many friends to militant training camps across the border. It also means attending funeral processions for many young men like himself.

Sajad’s story is punctuated by the valley’s outbreaks of violence, most of which never seem to enter the historical register: the Gawkadal massacre of January 20, 1990, when Indian troops murdered unarmed protestors on a bridge, or the targeted killing of Kashmiri Hindus a few months later and the fleeing of the remainder of the community. But it also touches upon the mundane difficulties of life in an entirely militarized society: of taking someone to the hospital for a test or to remove stitches (three checkpoints) or traveling to work (one arrest). There are bullets embedded in the walls of Munnu’s school and barbed wire surrounding it. The countryside is covered with tombstones. As he walks us along the meandering road of childhood, Sajad spares no ire for the various resistance groups that have been fighting India since the armed uprising began in 1989—largely supported and funded by Pakistan, often undiscriminating between military and civilian targets, ruthless towards minorities, racked by infighting or out for financial gain. There is also the cultural fallout that results from both decades of conflict and the Islamist turn: for instance those who attack the art of the band pather, folk theater of Kashmir that saved its carnivalesque queer critiques for local leaders, or groups like the Daughters of Kashmir, who spend their time cleansing school syllabi from indecent art. But Munnu’s central critique is reserved for the Indian state, whose “boots on the ground” (between 300 and 700,000) have been responsible for the most heinous forms of torture and war crimes, among them mass rape, mass graves, disappearances, and staged “encounter killings.”

There are bodies dumped in rivers at jagged angles, fathers clutching at the bones of their sons. There are doctors conducting autopsies on victims of mine blasts and torture, needling between ribs for evidence. All of this is told in comic-book form, though some of the frames look closer to Doré’s woodcut engravings of the Inferno, rich with finely grained textures, requisite corpses included, than any “comic” art. The immediate genealogy here is not Doré, however, but a tradition of Kashmiri walnut wood carvings, done by hand, that appear in some of the lattice-like backgrounds of these frames. And the corpses here are those of hangul, the deer in the valley, though they have human hands, rather than hooves.

In between these frames emerges the loveliest story of mother and son: a mother too modest to celebrate Eid with her children, for fear of offending those who haven’t been fortunate enough to hold on to their own; a son too devoted to let his mother suffer her intransigent cough without the Kashmiri apples that are said to be its cure. (At one point, he risks his life to find them.) Over the course of the book, a small world emerges, of care and intimacy in a home against whose doors the police are literally leaning, searching for militants. The insular world of the home becomes both bastion and prison.

In this way the graphic novel displays in its little boxes the consummate enclosure that is Kashmir, that historic Silk Road stop, now surrounded by checkpoints and curfews, shortages and blockades that make worldly connections all but impossible. Kashmiri journalist Basharat Peer mentions in his lyrical memoir Curfewed Night that a militant’s narrative was like that of Marco Polo, “bringing tidings of a new world,” the world of political possibility and the view from Pakistan, but also a wider world outside the confines of the valley. Indeed Munnu says, “The blue sky now seems the only sign that the rest of the world is out there.” The blue sky of the penciled graphic novel is, of course, black. And one of Munnu’s cartoons for the newspaper Greater Kashmir, as he begins his life in art, is a goldfish clutched in a plastic bag of water, captioned NORMALCY.

A bit of the world does eventually enter—a bit of the world that is neither India nor Pakistan—in the figure of Paisley, a young woman from Brooklyn who has come to do research on Kashmiri art. Her roamings about town bring into Munnu’s pages the engravings of Srinagar shrines and the old buildings of Batamaloo. As we discover the valley’s monuments, both natural and archaeological, we also confront the extent of the conflict’s ravages; the Parvati temple, for example, has been turned into a military camp. In the end the romance between Munnu and Paisley collapses, too, under the weight of a misunderstanding too large to carry. “It’s not all fucking breathtaking here!” says Munnu in desperation. Sympathetic foreigners beware.

As a result, we are left in the hands of Munnu alone, our friend and fledgling guide, who, himself, exasperated, says, “I don’t know the history well.” Subject to forces he doesn’t always understand, frustrated by illiteracy in his own Kashmiri tongue (all his schools enforce an Urdu medium), Munnu traces his political education, like Basharat Peer before him, through the world of art, informal conversation, circulating snippets of ideas. Ultimately, Munnu learns neither from books nor newspapers, neither from militants nor the Central Reserve Police Force. His university is the catalogue of his own experiences—watching a young boy fall to the ground next to him as they run from police fire, or being arrested by anti-terror police in Delhi for reading a Kashmiri newspaper online. When asked condescendingly by a European writer about the historical complexities facing his home, the young Munnu tells us, “I might not know where the bullet came from but I could tell her who the bullet hit.” In that sense, the graphic novel’s argument, if it can be called that, is for the tangible evidence of personal experience, and for a humanist understanding that somehow evades the frame. Indeed, as Munnu himself comments, “Without his own cartoon, the newspaper looked blank.” Munnu’s contribution is to insert the life of the ordinary Kashmiri—and his political critique—into the headline that is “Kashmir,” but also to create that very subject, of the Kashmiri, who is worthy of self-determination.

The circumstances facing Kashmir may be unique, but the valley’s plight is not without its analogs, and the space of the literary helps to reveal them. Basharat Peer, for example, reads Turgenev, Orwell, Dostoevsky, and Hemingway—especially Hemingway—and yet, “though [Hemingway] had written about a faraway war, I saw only Kashmir in his words.” He hands his friend Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and says, “You will see Kashmir here.” Despite economic and cultural blockade, Kashmiris see reflections of Kashmir everywhere.

And perhaps India is finding ways to see Kashmir as well. In the past year, performances in Kashmir and elsewhere in India of Albert Camus’s 1949 play Les Justes (The Just Assassins) have given new expression to questions of separatism and revolution. (Camus, too, was reading Hemingway.) In the play, Bolshevik revolutionaries sit in a spare room, debating forms of revolutionary action and the justification of violent means towards utopian ends. In Camus’s original the Russian revolutionaries have targeted the Grand Duke for assassination. In the version performed in Kashmir last May, based on a Hindi version of the play from the 1980s, the revolutionaries are Indian anticolonialists, set to assassinate the British governor. But in a series of recent performances in Delhi in 2008 by the Atelier theater group, and in Bombay by students at the Institute of Management Studies in 2014, the revolutionaries have been reimagined as Kashmiri separatists, and their target is an Indian deputy inspector general. Here, people are seeing Kashmir in Camus’s words—words spoken by the Bolsheviks in the original play, words that originally masked the condition of colonial Algeria. Camus’s lines, spoken by the militant Faisal, recently freed by a jailbreak—“How can one man be azaad unless we all are?”—have an immediate resonance in Kashmir, often cited as the “most militarized place on the planet.”

By putting Kashmir in dialogue with other times, other places, other colonies, these acts of literary and cultural translation evoke both a longer history and a renewed urgency. The signs on Munnu’s school wall, SPEAKING IN KASHMIRI IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED, recall Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s childhood in British Kenya; the barricades and curfews can only evoke Palestine.

In all of these dramatic adaptations, the actors debate rebellion, violence, and the nature of the revolutionary cause—debates that simmer around the edge of Sajad’s book as well. But the moral threshold is always the figure of the child: Josh, the figure for the poetic Kalyayev in Camus’s original, stops short of throwing the bomb, as the commander has his two little grandchildren with him. Children inevitably signify the future, as well as, here, the boundary of insurgency. Kalyayev, the Bolshevik, and Subhash, the anticolonialist, and Josh, the Kashmiri separatist, all abandon the call to arms picturing the child’s face. The graphic novel Munnu attaches a full life to that face, with all of the features that make the Bildungsroman so arresting—the seductions of youth, the transition to adulthood, first loves, first jobs, the failures and triumphs—along the way.

But that young life remains permeated by death. The last few years have taken an extreme toll on Kashmir’s young people; one journalist refers to 2010 in the valley as “the year of killing youth.” Indeed such indiscriminate violence has since 1990 become a structural aspect of the Indian army’s policy, legally sanctioned by the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which provides impunity for the killing of “militants,” defined, more or less, as all young men. The JNU students mentioned earlier can say the word azaadi out loud in part because the army will not open fire on them, even if today they face arrest under an increasingly repressive government. In Kashmir, student organizations are more or less banned, cell phone networks routinely blocked, and any public protest is under military threat. Just this April, an eighteen-year-old, twenty-year-old, twenty-one-year-old, and twenty-two-year-old were killed as the army set their guns on a protest in the town of Handwara. This follows the better-remembered massacres at Kunan Poshpora, Sopore, Tengpoora, Bijbehara, Saderkoot Bala, Sailan—a litany more or less tattooed on the arms of those who live it, but curiously unknown anywhere else, even, of course, in India. The political logic propagated by the state, that of the “internal affair” of Kashmir, has prevented any serious intervention by the international community in a conflict involving two nuclear-armed powers; the daunting geopolitics only trickle down, crystallizing to form Munnu’s insular, emboxed world. In “Night’s Triptych,” the great Kashmiri poet Dina Nath Nadim refers to this as both “the soft strangling” and “the sudden serpent’s bite.”

In Munnu’s story, the killings are routinized, as are the scenes of grief, protest, provocation, and burial; they are, in fact, the constitutive events of childhood. In one wrenching scene, Munnu and his tiny friends attempt to console each other after a fellow student opens the door to his father’s corpse on a stretcher, brought by the police; another boy wakes up to find his brother’s. “Want to watch a movie?” says one; “We’ll ask our headmaster to make you class monitor!” says another. But this show of empathy strains the children’s maturity, and the talk quickly turns to bomb making. Although the petrol bomb the boys concoct from broken light bulbs and batteries only succeeds in scarring the tin roof of the school, one sees in miniature how quickly the minor becomes a “militant.”

The irony, carried by the images, is that these so-called militants are small-horned endangered creatures—wide-eyed, big-eared baby stags. The brutalities of the past—those committed by the historical rulers of Kashmir, whether they be Mughals, or Afghans, or the Dogra maharajas—and those of the present, committed by soldiers, and police officers, and other representatives of the state, are committed by fully drawn men. In other words, the range of inhumanities in the novel is practiced by the “humans” sketched on the page—Indians and foreigners. These humans that Munnu meets, on the street, during a raid, or at an art gallery in Delhi, face off against the hangul across a great civilizational divide. “Kashmir is not India!” screams an exasperated Munnu to a group of European officials. In the space of these sketched pages, there are so many funeral processions, so many custodial deaths. But whose deaths are worth grieving? Surely not those of simple deer. The uncomfortable question suggested by the novel, and by Sajad’s clever personification (very different from Art Spiegelman’s mice and cats), is: what will become of the hangul? Without self-determination, Kashmiris become a species on their way to extinction.

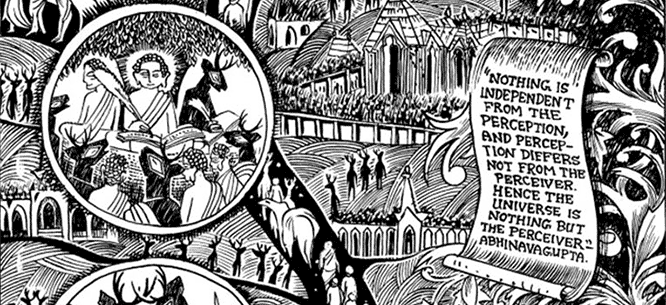

Desperation changes the way we see things. Young Kashmiris who might have simply watched before now throw stones. Some who used to throw stones have been directly putting themselves in the line of Indian army fire, to divert attention or to help militants escape. And tens of thousands attend funerals of young militants, seen as local heroes—Kashmiri nationalists, they say—who have been killed in action. In one episode, Munnu’s former teacher tells him the anecdote of the Prophet’s believer, who asks for the most appropriate wish for this world. “Pray thus: Oh Allah, show me things the way they are and not the way they appear to our eyes!” Later he quotes Abhinavagupta, the tenth-century Kashmiri Shaivaite philosopher who wrote that “Nothing is independent from the perception, and perceptions differ not from the perceiver.” Munnu has to defamiliarize its protagonists, transforming them into deer, in order to make them visible—so that they can be seen “as they are,” not “as they appear to our eyes.” And what we see, in fact, are fully drawn individuals seeking self-determination above all—a freedom earned, in this book, through a young boy’s process of self-reflection. In the final frame, the diamond-eyed deer Munnu ends up roaming the black boxes of night with a flashlight, searching.

Toral Gajarawala teaches literature in New York.