Full Employment and the Path to Shared Prosperity

Full Employment and the Path to Shared Prosperity

There are many policies that can reduce inequality, but there is none as straightforward conceptually and as difficult politically as full employment.

There are many policies that can reduce inequality, but there is none as straightforward conceptually and as difficult politically as full employment. The basic point is simple: at low rates of unemployment, the demand for labor allows workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution to achieve gains in hourly wages, annual hours of work, and thus income.

Levels of unemployment are not the gift or curse of the gods; they are the result of conscious economic policy. The decision to tolerate high rates of unemployment is a choice. It is one that has enormous implications not just for the millions of people who are needlessly unemployed or underemployed but also for tens of millions of workers in the bottom half of the wage distribution whose bar-gaining power is undermined by high unemployment.

Unemployment and Wage Growth

In discussions of inequality and low wages, many on both the left and the right claim that what we need is a better educated workforce. Their argument is that because educated workers are more productive and workers’ pay reflects their productivity, they will earn more if we can persuade them to get more education. However, while more education is generally associated with higher wages, this is just part of the story. In most jobs, the value of workers’ labor depends on the demand for their labor. A retail clerk in a store or a waiter in a restaurant is far more productive, meaning they are generating far more revenue, when business is strong than when it is weak. This means that, in a strong economy, employers can afford to pay a worker with the same level of education and training a higher wage.

Furthermore, when unemployment is low, workers are in a position to demand pay increases in accordance with their productivity. This is especially the case in parts of the private sector where unions are rare. A low rate of unemployment gives workers the bargaining power to demand a pay increase from their boss and to leave for new jobs if they don’t receive it. We saw this in the boom of the late nineties. The unemployment rate fell to its lowest levels since the early 1970s, bottoming out at 4.0 percent in 2000. From 1996 to 2000, workers up and down the income ladder saw substantial wage gains, as employers had to compete—to bid up their compensation offers—to get and keep the workers they needed.

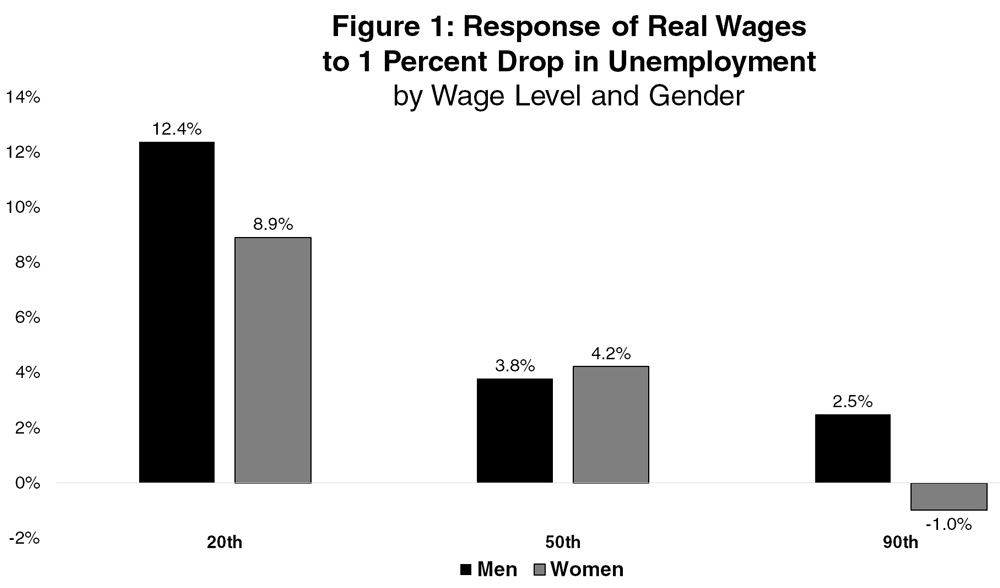

We found a consistent pattern between wage growth and unemployment. Low rates of unemployment are associated with faster rates of real wage growth, with the benefits concentrated among those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Figure 1 shows the basic story.

In a world where the unemployment rate is permanently 1 percent lower, wages for male workers at the twentieth percentile of the wage distribution would be 12.4 percent higher. Wages for women workers at the twentieth percentile would be 8.9 percent higher. Wages for male workers at the fiftieth percentile would be 3.8 percent higher and for women workers 4.2 percent higher. The impact at the ninetieth percentile is limited and not statistically significant in the case of women. These implied wage increases can be compared to an actual path where the wages of men at the twentieth percentile fell by 14.9 percent between 1979 and 2011 and wages of women at the twentieth percentile rose by 4.8 percent (about 0.1 percent per year).

Lower unemployment is not just associated with higher hourly wages for middle- and low-wage workers; it is also associated with more hours of work. A 10 percent reduction in the unemployment rate (for example, a reduction from 7.0 percent to 6.3 percent) is associated with a 2.5 percent increase in annual hours worked for households in the bottom fifth of the income distribution. Households in the middle fifth of the income distribution increase their hours by 1.2 percent on average. By contrast, a 10 percent drop in the unemployment rate is associated with an increase in annual hours of just 0.5 percent for households in the top fifth of the income distribution. In an economy where most workers at the top of the income distribution are working as much as they want, they don’t increase their hours much when the economy becomes stronger. On the other hand, workers at the middle and bottom of the income distribution often like to work more hours when they have the opportunity. A low rate of unemployment gives them this opportunity.

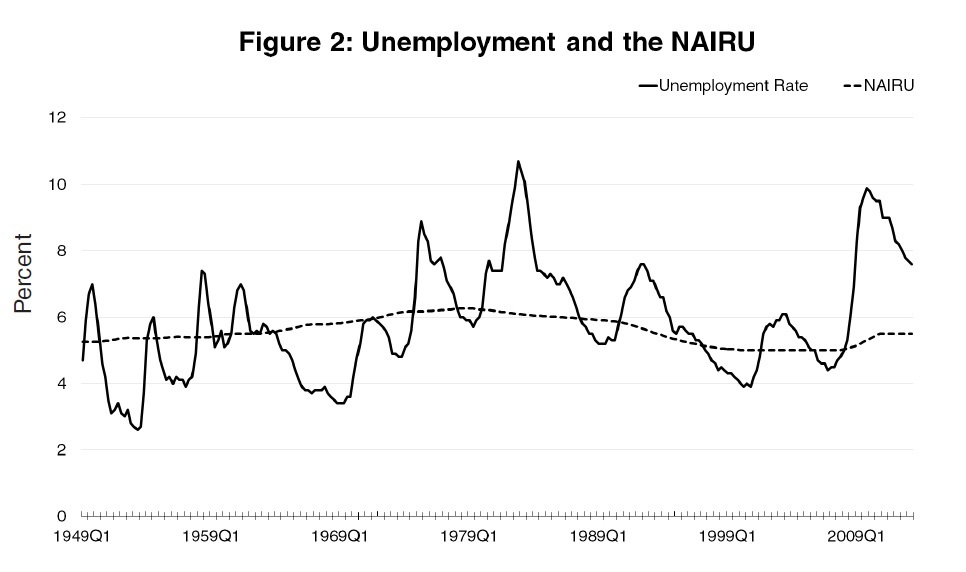

Because unemployment affects wages and hours for the middle class and the poor, the rate of unemployment is important in determining the distribution of income. High rates of unemployment are likely to be associated with an upward redistribution of income, whereas when unemployment rates are low, most workers share in the gains from economic growth. It is not surprising that we have seen considerably higher unemployment rates in the period of upward redistribution since 1979. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the actual rate of unemployment and the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) estimate of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU).*

The unemployment rate was generally below the CBO’s estimate of the NAIRU for most of the period prior to 1979. The unemployment rate has been above the estimated NAIRU for most of the years since 1979. From 1949 to 1979 the unemployment rate was a cumulative 15 percentage points below the NAIRU. From 1980 to 2012 it has been a cumulative total of 31 percentage points above the NAIRU. Even if we exclude the years following the Great Recession, the economy would still have been a total of 16 percentage points above the NAIRU. Clearly, the period of rising inequality has been associated with an economy that has high unemployment. While unemployment certainly is not the only factor leading to increased inequality, it is a large part of the story.

Getting Back to Full Employment

If high unemployment is one of the obstacles to more equitable growth, then the question is: how do we achieve full employment? There are four main ways. Each route faces substantial political opposition, both because of powerful interests that would be hurt by paying higher wages and because of popular prejudices that are persistently promoted in the media.

1. The Federal Reserve Board. The Federal Reserve has already pushed the overnight interest rate that it directly controls to zero, the lowest nominal rate it can set. However, if the Federal Reserve lowered the real interest rate (the nominal rate minus the inflation rate)—by raising the inflation rate—this could lead to increased investment and consumption. Paul Krugman and others support the idea that the Federal Reserve Board should commit itself to raising the inflation rate to 3 or 4 percent, thereby lowering the real interest rate. If businesses believe that the inflation rate will be 3 or 4 percent, then they will adjust their plans accordingly. For example, if they expect a 4 percent inflation rate over the next four years, this means that they expect they will be able to sell their products for 16 percent more four years from now than they do today. This will give them more incentive to invest and a willingness to pay higher wages if that is necessary to get qualified workers. The result would then be both more hiring and an inflation rate that is closer to the Fed’s target.

It is questionable whether this inflation-targeting strategy could work. Japan’s central bank has recently tried this and seems to have been somewhat successful. Prices have stopped falling there (Japan had been experiencing deflation) and have recently been rising at more than a 1 percent annual rate. This inflation rate is still less than the bank’s 2 percent target, but it is promising nonetheless.

Levels of unemployment are not the gift or curse of the gods; they are the result of conscious economic policy.

There seems little downside risk to this policy, but those who own debt are not anxious to see its real value eroded through inflation. In addition, there is a persistent myth that raising the inflation rate from very low levels (0 percent to 1.5 percent) to low levels (2 percent to 4 percent) is just a short step away from Weimar-style hyperinflation. The persistence of this myth makes it difficult to muster support for a more aggressive Fed policy and could make it difficult to sustain even the degree of stimulus we have seen to date from the Fed.

2. Government Spending. The story of how the government can boost demand and create jobs through stimulus should be well-known. In an economy where there is not enough demand from the private sector, the government can create demand directly by spending money. It can also create demand indirectly by cutting taxes. The impact of the latter depends on people’s willingness to spend any tax cut they receive from the government. Low- and moderate-income households are likely to spend a large share of any tax cut, because they need the money. More affluent households will save much of any tax cut. For this reason, direct spending is a better route to boost demand than tax cuts.

Any spending will create demand in the short term. Keynes famously joked about paying people to dig holes and fill them up again. Ideally, money spent to boost demand in the short term will also have beneficial effects in the long term. This was the goal of the portions of the 2009 stimulus package that were dedicated to upgrading infrastructure, modernizing the electricity grid, and supporting research in clean energies. The expectation was that spending in these areas would have longer-term benefits in the form of increased productivity and reduced greenhouse gas emissions on top of the immediate benefit of creating jobs.

The stimulus worked as intended, creating 2 to 3 million jobs. The problem was that the collapse of the housing bubble left a much deeper hole than the stimulus was designed to fill. We actually needed somewhere in the range of 10 to 12 million jobs. And the economy continues to suffer from inadequate demand.

The economy needs more stimulus. There is no shortage of areas—such as investment in our public goods, including both physical (infrastructure) and human capital—where government spending could help lay the basis for greater future prosperity. However, as a political matter, the prospect of any substantial new stimulus is at best remote.

For many years now, Washington policymakers have become obsessed with budget deficits. Republicans have consistently opposed more stimulus spending, and among Democrats who supported it, many remain reluctant to sign on to any additional spending without some offsetting budget cuts and/or increases in taxes. It is possible to write bills that frontload stimulus spending and backload offsets for that spending (to pay for the stimulus spending numerous years after it occurs), but even this has been beyond Washington’s capacity.

The decision not to have a stimulus and instead to reduce the deficit is a policy choice, not the natural order of things. The decision not to run deficits at a time of high unemployment is a government policy to keep the unemployment rate high. That may not be how proponents of low deficits view the policies they advocate, but it is the effect of these policies.

Here, interests that prefer higher rates of unemployment can readily appeal to widespread public confusion about debts and deficits. The metaphor comparing the U.S. budget to a family budget continues to be powerful. With few politicians of either party willing to challenge it, the idea that we would deliberately run larger deficits to boost the economy and create jobs is a very difficult agenda to sell.

3. The Trade Deficit. The current U.S. trade deficit is in the neighborhood of $500 billion a year (about 3 percent of GDP). This is money that is being spent but is not creating demand in the United States. It is the macroeconomic equivalent of increasing taxes on ordinary workers by $500 billion and doing nothing with the money. Needless to say, that would be a serious drag on the economy.

Getting the trade deficit down means lowering the value of the dollar. There have been many proposals for reducing the trade deficit through other mechanisms such as trade agreements or industrial policy. The history of the former has been mostly negative. Our trade deals have tended to be associated with larger trade deficits. Well-executed industrial policy can have a positive impact on the trade deficit, but even in a best-case scenario it would take a very long time.

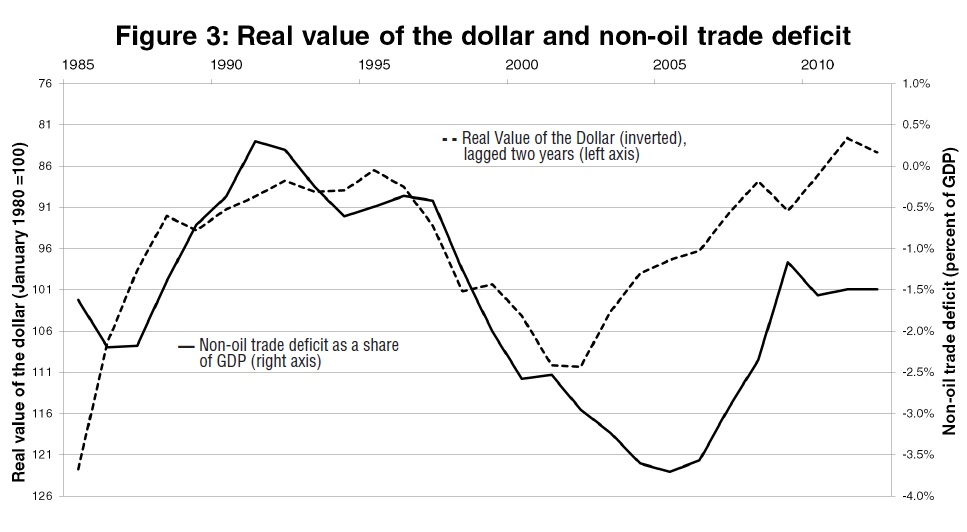

By contrast, a lower-valued dollar makes our goods and services more competitive immediately. The run-up in the dollar following the East Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s is the cause of the large trade deficits of the last fifteen years. Figure 3 shows the non-oil trade deficit against the value of the dollar shown with a two-year lag.

To get these deficits down, we will need to lower the value of the dollar against the currencies of our trading partners. We don’t have to catch China or other countries “manipulating” their currencies. China and other countries openly peg their currencies against the dollar. They buy up large amounts of dollars to keep their currencies down and the dollar up. We just have to get them to stop buying dollars. (Contrary to what the budget deficit fanatics tell us, we should want China to stop buying our debt. That is how they “manipulate” their currency.)

If we want other countries to raise the value of their currency against the dollar, we have to negotiate with them. This means giving up other demands, like enforcing Microsoft’s copyrights or Pfizer’s patents. Or it means not pressing for greater access for J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs to overseas financial markets. There is undoubtedly a set of concessions that we can make to China and other countries that will persuade them to raise the value of their currencies against the dollar.

The reason that this has not been done to date is that the Obama administration places a greater priority on the demands of U.S. businesses than on bringing the economy to full employment. That may not be easy to change given the power of business, but it is important to understand. We have a large trade deficit, and therefore high unemployment, because it would be inconvenient for powerful business interests to have a smaller one.

There is some bipartisan support for reducing the value of the dollar as a tool to get the trade deficit down. However, this support runs up against the many powerful interests that benefit from an overvalued dollar both directly and indirectly. The group that benefits directly includes large retailers like Walmart that have invested large amounts of money in setting up low-cost supply chains. Most major manufacturers have also outsourced a substantial portion of their capacity. Neither will be anxious to see the price of the items they import rise by 20 to 30 percent.

In the indirect category, companies like Microsoft and Pfizer demand that the government work to increase enforcement of their copyrights and patents in China and elsewhere. The financial industry demands more access to foreign markets. If the United States were to win concessions on currency values, it would likely mean making concessions on enforcement of copyrights and patents or market access for the financial industry. This is a trade that top political figures in both parties are not anxious to make.

It also doesn’t help that the media almost never discuss the trade deficit and even more rarely point out the simple accounting identity that demand going overseas is demand lost to the United States. As a result, the public is generally kept in the dark regarding the fact that the trade deficit is one of the largest obstacles to full employment at this moment.

4. Sharing the Work. The final route for getting to full employment is reducing the average number of hours per job. This can be done through a variety of mechanisms. The most obvious is work sharing. This involves getting employers to cut back workers’ hours rather than lay them off. Twenty-six states, including California and New York, already have work-sharing programs in place that operate through their unemployment systems. Instead of paying a worker half pay to be completely unemployed, the work-sharing system makes up half of the pay for the hours that a worker loses. If, for example, a worker’s hours are cut by 20 percent, then the unemployment insurance system makes up half of the lost wages. This would mean that the worker only sees a 10 percent reduction in wages. If this goes along with a four-day workweek, saving the worker the expense of commuting and other work-related expenses, the net loss in income might be relatively modest.

We have a large trade deficit, and therefore high unemployment, because it would be inconvenient for powerful business interests to have a smaller one.

Germany has used work sharing with great success. Its unemployment rate has fallen to 5.2 percent from 7.8 percent at the start of the downturn even though its growth rate has actually been slightly lower than that of the United States. The program enjoys support from across the political spectrum as both business and labor see the value of keeping workers attached to the firm, building up skills, rather than a prolonged period of unemployment where they risk becoming permanently detached from the labor market.

Work sharing also has had bipartisan support in the United States. Republicans in the House supported an amendment to a bill in 2012 that requires the federal government to pick up the tab for state work-sharing programs through 2014. The federal government will also cover the cost of setting up programs in the states that don’t currently have work sharing and modernizing the systems in the states that do.

There are other steps that can be taken to reduce average work hours. Paid sick days and family leave are both important sources of flexibility that allow workers to balance the demands of their job and their family. They also have the effect of reducing the average number of hours worked in a year. Paid vacation is another way of reducing work hours. The United States is an outlier in not mandating that workers have some number of paid vacation days or holidays in a year. In many countries the standard is five or even six weeks a year. The average work year in most of Western Europe has 15 to 20 percent fewer hours than in the United States. While shortening hours may not lead to a proportional increase in jobs, there can be little doubt that fewer hours per worker means more demand for workers.

This is also a policy that can be pursued at the state and even local level. For example, if people in California and Washington state want to ensure that their workers enjoy two to three weeks of paid vacation or paid family leave after the birth of a child, they can vote to do so, as they have in fact done in the case of family leave in California. This is a policy that can directly improve people’s work lives and lead to more people being employed.

The route of reducing work hours to increase employment must overcome the general lack of interest in promoting full employment in our political system. In addition, it seems to tax the imagination of many people involved in the debate over economic policy. For example, early in President Obama’s first term in office, some senior officials worried that work sharing was simply a way of “spreading around the pain” of weak labor demand, as opposed to creating more jobs.

High unemployment is an incredible waste of resources; people who have skills that are needed and want to work are being denied the opportunity. And it has a devastating impact on the lives of the people affected. Workers experiencing prolonged periods of unemployment often suffer from alcoholism, depression, and a wide range of physical ailments. Long-term unemployment increases the probability of divorce and is destructive to children in the household. For these reasons we should do everything we can to reduce the rate of unemployment.

High unemployment also affects the employed. The bottom half of the workforce only has the bargaining power needed to ensure that it gets its share of the gains from economic growth if there is low unemployment creating a tight labor market. We saw this in the late 1990s, but we have not seen it since.

A tight labor market may prove especially important if we see the surge in productivity that some economists predict as robots displace larger numbers of workers. We doubt that robots will do all the work (we have heard it before), but there is no reason that this should be a bad thing in a properly functioning labor market. There are many examples of industries in which a rapid rate of automation has been associated with sharp reductions in work hours and increases in pay. This is what we should want to see. Robots could give us all more time and a better standard of living. Unfortunately, that is not the world that we are looking at today.

Dean Baker is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.