Cowboy Confederates

Cowboy Confederates

The ideals of the Confederate South found new force in the bloody plains of the American West.

How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America

by Heather Cox Richardson

Oxford University Press, 2020, 272 pp.

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

by Walter Johnson

Basic Books, 2020, 528 pp.

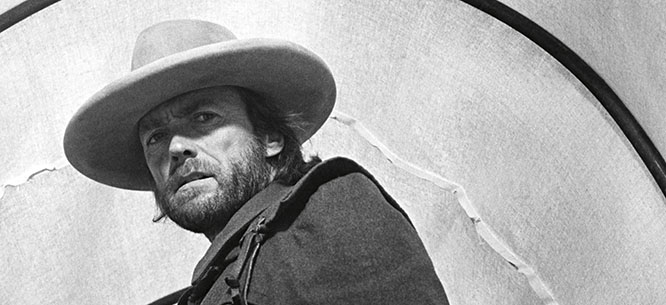

The Clint Eastwood Western The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), a genre-defining fantasy of anti-government violence, finds redemption for the failed ideas of the white South in the bloody plains of the American West. Eastwood’s character, and the entire idea of the American West in the film, are the product of two of the biggest blows against white supremacy in U.S. history: the Civil War and the civil rights movements. The book on which it was based, The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales (1972), was written by a former Klansman named Asa Earl Carter who went by the pen name Forrest Carter (a nod to Confederate hero and Grand Wizard of the postbellum Ku Klux Klan, Nathan Bedford Forrest).

Carter had been on the lunatic fringe of the struggle to maintain white supremacy in Alabama during the 1950s and 1960s. His biggest claim to fame was writing George Wallace’s 1963 inaugural gubernatorial address, which included the infamous line, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” As the civil rights movements advanced, however, Carter came to believe that George Wallace and even the KKK were too soft for his particular brand of racism. So he moved to Texas. Out west, he rebuilt his identity and carried forward the struggle to maintain his idea of freedom.

Carter’s book, and Eastwood’s movie, tell an allegorical story of a Missouri farmer who loses everything to a merciless band of Union soldiers who slaughter his family and burn his home after the Civil War. In the novel, the desperate Wales nails G.T.T. (Gone to Texas) on his door and joins a guerrilla band of Confederates who exact their revenge on the soulless Yankee intruders. In one famous scene from the movie, Eastwood wipes out an enormous swath of Union soldiers with a Gatling gun. The Civil War never ended for Josey Wales, just like it—and the struggle against the civil rights movement—never ended for Carter himself. The film’s initial director, Philip Kaufman, who was eventually fired by Eastwood, found the whole story of redeeming the Confederacy in the West through violent anti-government rebellion to be “fascist” and “nutty.”

The historian Heather Cox Richardson also finds the connection between South and West troubling—but accurate. In How the South Won the Civil War, Richardson shows how once-defeated ideas and politics stayed alive and then flourished by moving west. “In the West,” she writes, “Confederate ideology took on a new life, and from there, over the course of the next 150 years, it came to dominate America.” White Southerners continued their resistance to federal incursions on white supremacy through a geographic shift to what they saw as “the only free place left in America.” They believed that Reconstruction-era “Republicans who passed laws to protect freed people were not advancing equality; they were destroying liberty.” The mythology (and she stresses that most of it was myth) of the American cowboy took on the individualism that once belonged to the Jeffersonian yeoman. Both stock characters were capable of heroic feats of grit, pluck, and determination.

The revenge fantasy of the West was a renewable resource even after the 1960s—a trend that culminated with Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, who won only Arizona and the Deep South in 1964. The nation then moved on to a second-tier cowboy actor and California politician, Ronald Reagan, who notoriously opened his campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where he touted states’ rights near the site where three civil rights organizers were killed. Building on Nixon’s Southern Strategy, Reagan won the former solidly Democratic South in his successful push to reach the White House.

Richardson examines not just the ideological ties between the Confederate South and the American West, but how the notion of freedom they held in common served as a powerful cover for oligarchic power. The rhetoric, the sentiment, and the racialized ideal all served the material interests of the country’s most powerful people. Across the centuries, she argues, business elites “came to believe that they alone knew how to run the country.” And to preserve their brand of freedom, they believed it was “imperative that others be kept from power.” In the South and then the West, these oligarchs “suppressed voting, rigged the mechanics of government, silenced the opposition press, and dehumanized their opponents.”

These forces opposed activist governments from Reconstruction through the New Deal to the Great Society. “As the only ones who truly understood what was good for everyone, they were above it,” Richardson writes. “So long as they continued to project the narrative that they were protecting democracy, their supporters ignored the reality that oligarchs were taking over.” Her argument clearly still rings true for conservatism from Reagan through Trump, a period in which the political system has moved from a messy, crosshatched party system to one sorted, organized, and polarized by region and ideology.

The historical characters in Richardson’s book are well known, but she has fit them together in a way that provides new insights. Her pacing stumbles a bit as she covers too much territory, which ends up giving the book some textbook padding that dulls an otherwise sharp argument. Richardson is most in command on her home turf—she has written brilliant books on Reconstruction, the West, and the Republican Party. Dissecting carefully the ways in which freedom served as a front for hierarchy and power by the privileged few, detailing the clear gender, race, and class dimensions throughout, she nonetheless remains unsteady about the nature and origins of the “great paradox” of freedom and power.

Sometimes, in her telling, the tension between freedom and oppression is central to the creation of the republic, as argued in Edmund S. Morgan’s landmark American Slavery, American Freedom (1975). Other times she claims the Confederacy was based on the principle that the founding fathers were “wrong,” without exploring the many ways in which the Constitution proved foundational for the slaveholding regime. She ends up with a compromise position: that the United States was born of idealism but matured in “an environment that limited that right to white men of property.” This is a frustrating series of dodges for anyone who is interested in trying to figure out an urgent question that in recent years has resonated far beyond the confines of history departments: whether there is something salvageable in the founding ethos of the United States, or whether it was hopelessly shaped from the start by a commitment to a racialized brand of freedom. She also avoids the many forms of populism in U.S history, which might help illuminate the tension between popular freedom and power. Quibbles aside, How the South Won the Civil War is an important book for what we can only hope will be a new age of thinking about the nature of race, region, and ideology in this nation.

Before Josey Wales’s life was viciously destroyed by a right-wing celluloid fantasy of federal authority, his Jeffersonian idyll was in the state of Missouri. As Walter Johnson shows with a furious passion, the spirit of much of this great, ongoing civil war for the hearts and minds of American citizens could be found in the city of St. Louis. In The Broken Heart of America, Johnson reveals the city to be a gateway to “empire and anti-Blackness.” Johnson’s book ranges from the westward explorations of Lewis and Clark (the latter’s treaties added 419 million acres of territory to the United States and precipitated the forced removal of 81,00 Native Americans) to the Ferguson uprising against the police killing of Michael Brown. It’s a grim history that details the triumphant expansion of a virulent and violent racialized capitalism.Johnson’s book is full of refreshingly unfiltered statements, rare in academic prose. “St. Louis was home to the frontline force of exemplary imperial punishment: annihilation,” he writes. As “the morning star of US imperialism,” the bustling, violent, tawdry, racist city became an origin point for white-settler imperialism and ethnic cleansing beyond the Mississippi. This is a significant correction to forms of radical critique based more narrowly on labor-capital relations. “Viewed from St. Louis, the history of capitalism in the United States seems to have as much to do with eviction and extraction as with exploitation and production.”

Terms like “extermination,” “white power,” and “genocide” orient the reader for a violent ride through the dark heart of America. The historical tour proceeds through labor disputes, the Great Migrations, the first Congress of Racial Equality lunch counter sit-ins, the story of the housing project Pruitt-Igoe, and the city’s role as an incubator for a wide array of struggle and experimentation in civil rights, black power, and economic justice. Johnson even reveals how St. Louis’s poor neighborhoods were used as experimental zones in radiological and chemical weapons research. The story culminates in the disastrous urban planning and deindustrialization that ended any hope of St. Louis remaining among the great major American cities. In the end, even Anheuser-Busch, the Budweiser manufacturer whose tagline used to proudly announce its affiliation with St. Louis, sold out to a European conglomerate.

Richardson would likely agree with many elements of Johnson’s argument, especially his claim that the “the pathway to freedom in the late nineteenth-century United States was through Indian killing.” But Johnson goes further, insisting that the reunification of the United States itself came “in the service of capitalist expansion.” Richardson’s book, which avoids direct engagement with capitalism, leaves us with a lingering, if greatly diminished, faith in the American project. Johnson’s view of U.S. history, in contrast, is thoroughly jaundiced.

In 2003, Johnson wrote an insightful critique on the subject of agency within slavery studies in the Journal of Social History. Why do historians celebrate agency, revolt, and resistance, he asked, to a point where structures of domination become obscured? Why do social historians spend their time grubbing around for signs of resistance at the expense of studying power? He took these questions to heart in River of Dark Dreams (2013), a penetrating history of capitalism and slavery in the Mississippi River Valley.

I support Johnson’s project to reexamine agency and structural power in U.S. history but wonder if The Broken Heart of America went a little too far in rebalancing the scales. Racism is built, brick by brick, less into what he calls a “crucible” than into an impenetrable fortress of racialized capitalism. This is reflected in the narrative style of the book, which tends toward the “tell” rather than “show” variety: race and capital define the city; ethnic cleansing poured out of its gates, rolling across the land like a juggernaut. He’s right. But the unrelenting tale of the legal, social, economic, and political structures of oppression ends up too monolithic, without needed dialectical tension. Most people appear as little more than victims or perpetrators of a campaign in “service of empire and capital: to war in the name of white homesteads; to low wages subsidized by segregation; and to social isolation and cultural monotony understood as suburban exclusivity.” Johnson leaves us without much space to figure out how the world can be changed.

Still, what he reveals about contemporary St. Louis is horrific. Johnson explains how local business interests have allied since the 1980s to make money from the African-American people whose labor was no longer needed in the deindustrialized economic landscape. Tax abatements, the payday loan industry, revenue generated from traffic harassment, and for-profit policing—all these activities exploit poor people of color in order to extract money from a broken system.

This is the crucial backdrop to the social explosion in nearby Ferguson. “The two-hundred-year history of removal, racism, and resistance,” explains Johnson, “flowed through the two minutes of confrontation on August 9, 2014,” when officer Darren Wilson gunned down Michael Brown. Johnson also tells a lesser-known tale of police violence from 2011, in which a different officer carrying an automatic weapon chased after a black man. His bodycam recorded him saying, “We’re going to kill this motherfucker.” He fired five shots into his victim’s car before planting false evidence on his corpse. The echoes of Josey Wales’ Gatling gun ring on.

Jefferson Cowie teaches history at Vanderbilt University. He is the author of Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class among other books.

Correction: An earlier version of this review claimed that a police officer in 2011 chased after a man legally carrying an automatic weapon. The police officer was carrying the weapon. We regret the error.