Philanthropy for Radicals

Philanthropy for Radicals

The Garland Fund was not a typical foundation, but its history shows the potential role philanthropy can play in moments of rising authoritarianism—and the tensions inherent in that role.

The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America

by John Fabian Witt

Simon & Schuster, 2025, 736 pp.

In 1922 the American Fund for Public Service received two requests for money from people who would become famous campaigners for labor rights and racial justice. One came from union organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who admitted that she had “tried very hard . . . not to ask rich people for money” and “dislike[d] intensely to apply,” but needed funds for the defense of jailed anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The other letter came from A. Philip Randolph, who would go on to found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and plan the March on Washington. At the time, Randolph needed funding to keep The Messenger, the Black socialist magazine he started, afloat. Randolph also wrote with reluctance, having called the donor behind the foundation a “mental nut” and a “simpleton” just the year prior. Under normal circumstances, coming hat in hand to a foundation while promoting leftist causes would have been unwise, if not foolhardy. The American Fund, or the Garland Fund as it was known, was not, however, an ordinary foundation. The requests were quickly approved.

As Flynn and Randolph both knew, the recipient of their appeals, Roger Baldwin, shared their radical politics and skepticism of private philanthropy as a potentially corrupting influence. When he founded the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920, Baldwin had designed it as a membership-based organization of dues-paying individuals to deliberately avoid the sway of elite donors. “No work can be democratic which is supported by one class for the benefit of another,” he wrote. Such sentiments picked up on a debate active in the halls of Congress and on union shop floors in the 1920s about the threat—or “menace,” as one contemporary critic charged—to democratic society posed by the creation of philanthropic foundations with increasingly large endowments and increasingly broad missions.

Yet that very same year Baldwin found himself head of a foundation established by a recalcitrant, radical young millionaire whose first instinct was to refuse his inheritance—a bequest from his grandfather’s career in finance worth the equivalent of $18 million today—which came due on his twenty-first birthday. Press coverage of Charles Garland’s refusal generated guffaws and offers to take the wealth off his hands, as well as a few paeans from admirers who celebrated Garland’s unwillingness to participate in a political economy rooted in exploitation and inequality. It also generated a proposal from none other than muckraking journalist Upton Sinclair, who beseeched Garland to use the money to build a better world. Sinclair admitted to the contradictions in using the proceeds of capitalism to dismantle its very foundations but argued to Garland that “such is the complexity of life.”

After several rounds of correspondence, Sinclair introduced Garland to Baldwin as a like-minded thinker. By 1922 the two had hatched a plan to use the inheritance to endow a new entity, the American Fund for Public Service, to test whether wealth could attack inequality. With a small board—never more than thirteen members—and an impressive cadre of advisers, Baldwin ran the Garland Fund for the purpose of “experimenting with new institutions” and upending “present means of producing and distributing wealth.” Using the spoils of capitalism to construct a new world rooted in labor rights, racial justice, and democratic institutions was a plan as radical as the politics the foundation underwrote.

Today the philanthropic scene is dominated by large liberal foundations and a parallel network of conservative institutions. But John Fabian Witt’s chronicle of the Garland Fund’s two decades of existence (the board decided to spend the entirety of the endowment and closed shop in 1941) makes a compelling case for how and why philanthropy might support a leftist agenda. The Radical Fund may not convince everyone on the left that philanthropy is anything but an expression of plutocratic power. But this may be a moment—not unlike that when the Garland Fund operated—to embrace Sinclair’s “complexity of life,” or what Baldwin later called a “hypocrisy” that “tends to take you from where you are to where you want to go.” The radical potential of philanthropy is something those on both the giving and receiving end of philanthropy must grapple with as we struggle through another era of repression, violence, and inequality.

With meticulous detail, The Radical Fund offers a collective biography of the people, organizations, and ideas this pot of money brought together. To guide the foundation, Baldwin built a board “intentionally mixed” with liberal and leftist thinkers—those active in movements for free speech and civil liberties, union organizing and labor rights, and racial justice; those with socialist and communist affiliations, and with backgrounds in law, economics, and journalism; and those who had arrest records or, like Baldwin, had spent time incarcerated. As Witt points out repeatedly, the Garland Fund’s modest size, unconventional approach to giving, and leftist politics meant it could not have looked more different from other foundations at the time.

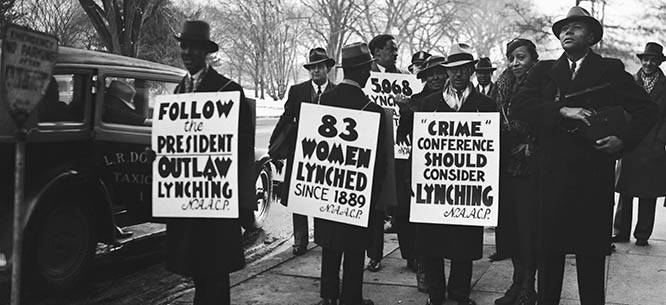

The book’s cast of characters is a who’s who of early-twentieth-century activism, and the money underwrote what Witt calls “nearly every controversial cause of the age.” Funds supported W.E.B. Du Bois’s study of Jim Crow schools; Clarence Darrow’s 1925 defenses of both John Scopes for teaching evolution and Ossian Sweet for defending his home against a white mob in Detroit; legal teams for Sacco and Vanzetti as well as the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama; A.J. Muste’s Brookwood Labor College, founded to teach the art of organizing; union drives by the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; and the NAACP’s early campaign against lynching as well as its blueprint to dismantle Jim Crow via litigation. Grants—and sometimes loans—supported bail funds, radical publications, and research. Witt’s background in legal history is on full display in his attention to several key court decisions that Garland Fund resources supported, such as Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad, which established equal treatment for Black workers from unions and employers.

In linking such famous episodes in U.S. history to a little known foundation, Witt makes an argument about the potential of philanthropy to create institutional change. In Witt’s telling, the fund’s resources “allowed its directors to put issues on the political agenda” and “offered a safe harbor during lean years for the labor movement,” among other accomplishments. Yet he is careful not to overplay his hand, concluding that “the American Fund did not secretly and single-handedly undo the old Jim Crow, shrink economic inequality, or produce the new law of free speech.” Those changes came from economic shocks, world wars, mass organizing, and demographic changes, but “when crisis arrived, the ideas, institutions, and movements of the Fund’s interwar workshop were ready to reshape America.” It is simply enough, Witt suggests, for the Garland Fund to have played a critical role at some particularly vulnerable moments. He presents landmark achievements as products, in part, of a marriage of private giving and radical ideas. Credit need not go to the fund alone for credit to be due.

Yet in playing up philanthropy’s ability to nurture, The Radical Fund misses an opportunity to more critically discuss money’s potential to distort activities on the ground. Baldwin and his fellow board members may have been underdogs in the world of foundations, but they wielded significant power over grantees. Theirs was a critique of philanthropy as an institution of wealth concentration, and not of grantmaking as a means of distributing it. What made the Garland Fund a radical funder lay more in what it funded than in how it did so; it still relied on a small, appointed board to make grant decisions behind closed doors. A deeper discussion in The Radical Fund of the stakes for grantees between, say, receiving resources as a grant versus a loan, or of matching requirements, would have provided a more nuanced portrait of how funding shaped organizational capacity, priorities, and strategies. (The fund’s inability to recoup most of its loans, however, and eventual conversion of many into grants suggests the limits of funder power.)

Witt’s central, and largely only, gesture toward the power asymmetries of grantmaking concerns the Garland Fund’s support of the NAACP. It is a compelling and complicated example of philanthropy’s power to shape organizations or “capture” them, as political scientist Megan Ming Francis has argued. The Garland Fund included the NAACP in its earliest rounds of grantmaking thanks to advocacy by James Weldon Johnson, who served simultaneously as the executive secretary of the NAACP and a founding board member of the Garland Fund. The sole African American member of the board, “no one would exert more lasting influence on the Fund,” Witt argues, than Johnson did by centering racial justice as a funding priority. Yet from the start, the funder-grantee relationship was one of support wrapped in austerity and restrictions, with grants trimmed in amount (a 1922 request for $10,000 netted, at least initially, a $2,500 grant with a matching requirement, and a 1929 proposal for $300,000 became a $100,000 commitment), subject to delays and scrutinous votes on payment releases, and increasingly laden with expectations in the 1930s that the NAACP prioritize civil rights over anti-lynching and hire a white lawyer to lead the effort. Such treatment stemmed in large part from a bitter divide that had emerged on the Garland board between the leftist and liberal factions, and it had clear consequences for its grantee, which “could do little but listen” and comply.

The issue with such practices is not whether they were strategic or produced good results, but that they came from a funder. “Holding the purse strings,” Witt explains, “meant that the American Fund’s directors retained ongoing power over the NAACP.” At issue was process, not outcome. The Garland Fund proved unquestionably important in seeding what would become the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, but it is also meaningful that decisions were made at the behest of those with the power to choose and that internal dynamics at the fund undermined its grantee’s capacity and autonomy. Even as the Garland Fund recognized racial justice as essential to modern democracy, its board members ignored how their own grantmaking practices reinforced the dependency of racial justice organizations on the preferences of a majority-white entity.

The discussion of the Garland Fund’s treatment of the NAACP—which Witt continues in the footnotes and in a published debate with Megan Ming Francis—is an exception, not a theme of the book. Perhaps Witt rationalized that enough critiques of philanthropic power already exist. Many writers on the left, including in this magazine, have argued that the massive fortunes, tax exemptions, and limited transparency underlying big philanthropy further concentrate elite power in ways that are at odds with democratic norms. The publication of critiques of philanthropy in popular outlets such as Teen Vogue and the success of Anand Giridharadas’s Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World attest that these opinions are now mainstream. Rather than settle the debate about the merits of philanthropy writ large, The Radical Fund accepts it as an imperfect tool and instead provides evidence of how it has been wielded toward egalitarian ends. It’s a useful lesson in our current political moment. After all, as Baldwin and others involved in the Garland Fund realized, debating the relationship between philanthropy and democracy matters little when authoritarianism is at the door.

It is either perfect or poor timing that a book on the creation of a more modern democracy is being released in a moment of its profound undoing. We are reminded daily of how fragile the Garland Fund’s contributions to causes such as free speech, civil liberties, worker rights, racial justice, and democratic practices were, and how seemingly inadequate our existing tools are to defend them.

Weeks before The Radical Fund’s publication, the Trump administration escalated its war on foundations. After threatening to tax endowments and supporting legislation that would expand federal oversight of nonprofits deemed to be supporting “terrorist” activities, Trump instructed the Department of Justice to investigate George Soros’s Open Society Foundations. (Disclosure: Dissent has received grants from OSF.) The selectivity of his brazen attacks makes clear that his issue is not with the existence of foundations—something he is quite comfortable with so long as it enables his own agenda—but with their involvement in liberal or leftist causes.

In response, many in the field are clinging to the threadbare myth of philanthropy’s neutrality. Some have preemptively retired DEI initiatives or renamed them. Over 100 foundation executives released a letter emphasizing civility, unity, and free expression in an attempt to deny the politicization of philanthropy. This response is understandable, though likely misguided, as leaders in higher education are learning. As activists and academics have long argued, philanthropy is fundamentally political, and painting it as anything else will do little to protect against attack or inspire the left to join philanthropy’s defense. There may well be risks in promoting philanthropy’s political potential and highlighting its historical support of anarchists, communists, and agitators, but The Radical Fund presents a compelling case for meeting this moment with bold action.

At a practical level, funders might take several cues from the Garland Fund: increase payouts or opt for a spend-down model to get more resources out the door; invest in public opinion (or “narrative change” in today’s parlance) by supporting publications, outlets, and local media to combat misinformation; loosen expectations for formal evaluation or proof of impact and accept the contingency and complexity of creating social change; frame worker rights and a fight for racial justice as linked efforts and not rival priorities; use resources for bail funds and the defense of those jailed, arrested, or targeted; support movements during the quiet periods and have patience for when change might occur; appoint movement leaders with unpopular politics to boards of directors and program officer roles; and recognize organizing and litigation work as rooted, as Witt writes, in “the same emancipatory project.” Grantees, as well as some funders, have been making the case for such practices recently without knowing they are part of a much older tradition. At a broader level, the Garland Fund’s interest in creating new institutional forms, organizations, and alliances might inspire similar thinking today. So too should its open embrace of radical politics that, as Baldwin wrote, “no established foundation would dream of touching.”

Other elements of Garland’s history are harder to replicate. A board comprised entirely of critics of philanthropy is unlikely at the largest foundations today, though foundations might include more skeptics on their governing bodies or staff. Smaller funders, like Garland, have more potential to build boards with movement ties. The emergence of intermediary or collaborative funding pots dedicated to decolonization, reparations, and justice movements offer another way to direct resources to entities closer to the grassroots. And while Charles Garland was unusual, a growing movement of young people with wealth are following in his footsteps through groups such as Resource Generation and the Solidaire Network. Additionally, changes in nonprofit law during the second half of the twentieth century—notably the creation of the modern tax code in 1954 and constraints on foundations via the Tax Reform Act of 1969—have made it harder, though not impossible, to pursue some of the kinds of political giving the Garland Fund pursued due to regulation of what constitutes advocacy and political activity. (Arguably, these reforms did not do enough to constrain philanthropic power and have enabled the rise of “dark money,” largely on the political right, working to undermine the priorities Baldwin and his allies worked for. Proposed reforms to curtail philanthropic power—such as requiring higher annual payouts and, of course, increasing taxes on wealth—deserve sustained attention.)

Some elements of the Garland Fund’s grantmaking hold more ambiguous lessons. The “mixture of forces” that Baldwin assembled for the board connected the foundation to a wider network of liberal and left causes but devolved into rival factions at times and slowed the process of moving money out the door. The board also vacillated over whether to have an explicit strategy of grantmaking priorities, as well as over rules by which it would disperse funds. There is no clear exportable best practice. Yet even ambiguous lessons have utility: Witt’s narrative reminds readers of the uncertainty and cacophony inherent in doing something new and different, and that the likelihood of uneven results is not a reason for inaction.

Perhaps more than anything, The Radical Fund serves as a reminder that the work many are already doing to pursue a left-wing vision of philanthropy exists in a much longer historical continuum in which change, insufficient and fragile as it was, did occur. Not all readers will agree with Witt’s conclusion that philanthropy—which cannot exist without inequality—can meaningfully advance the left’s egalitarian agenda. But the possibility of a more radical version of giving, and the recognition of the important role resources can play in progressive movements, is worth debating while these institutions still exist.

This book does not—and could not—resolve the tensions between philanthropy, democracy, and capitalism. The Radical Fund does something more valuable by inviting readers to acknowledge that tension and work within it: to be skeptical of philanthropy and still defend it from authoritarian repression; to embrace this imperfect tool and work to reimagine it; to recognize the anti-democratic nature of private giving and direct it toward the building of a more just democracy; and to acknowledge philanthropy as a political tool and use it to support those advancing a new political-economic order. Doing so, the example of the Garland Fund suggests, helped steer the United States away from fascism once and might just do so again.

Claire Dunning is an associate professor at the University of Maryland in the School of Public Policy and, by courtesy, the department of history. She is a senior fellow with the Institute for Public Leadership and author of Nonprofit Neighborhoods: An Urban History of Inequality and the American State.