Trump and Musk’s War on Workers

Trump and Musk’s War on Workers

Organized labor and its allies can and must do much more to respond to the crisis created by DOGE and the Trump administration.

We are currently experiencing something no one living has seen before in the United States. The events now unfolding are not merely the result of an election shifting political power from one party to another during a deeply partisan time. These events also herald more than the end of the international liberal political order that evolved from the New Deal to neoliberalism. We are witnessing a regime change in America.

The new regime’s brazen aggression and extreme goals are most visible in the frontal attack on the U.S. federal workforce, which has witnessed the gutting or disabling of several agencies, layoffs at virtually all others, the shredding of collective bargaining contracts with federal unions, and an attempt to effectively break the civil service.

The leaders of this effort told us long ago that this is what they had in mind. In September 2021, J.D. Vance laid out this vision with shameless candor to a conservative podcaster. What Donald Trump should do if he regained office, Vance said, is “fire every single mid-level bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state” and “replace them with our people.” And “when the courts stop [him],” he said, “because [he] will get taken to court,” Trump should “stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did and say the Chief Justice has made his ruling, now let him enforce it.”

The arrival of this moment has brought the American labor movement to a crossroads. Not since President Ronald Reagan broke the illegal air traffic controllers’ strike in 1981 by firing and permanently replacing the strikers has an administration’s treatment of federal workers threatened to impact U.S. labor relations as broadly and profoundly as the recent actions of President Donald Trump and Elon Musk. Reagan’s breaking of the walkout by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) inspired a torrent of private sector anti-unionism that saw employers break a host of prominent strikes in the 1980s, dealing a devastating blow to the union movement and hurting workers more broadly. Yet compared to the current administration, Reagan’s approach to the PATCO strike was mild.

Trump and Musk’s actions are shaping up to be worse than Reagan’s union busting, not only for federal workers, but also for workers across America. As the nation’s largest employer, the federal government’s labor relations policies inevitably ripple across the economy, influencing how employers of all kinds behave. Not only do they threaten to weaken unions, as Reagan’s breaking of PATCO did, they jeopardize the entire edifice of workers’ rights erected over more than a century.

Comparing the crisis the PATCO strike created for labor to the one that workers and unions currently face is instructive. Doing so reveals not only how much more dangerous the threat posed by Trump is, but also how much more vulnerable Trump might become to a well-organized, principled, and determined resistance, something that never developed in 1981.

Neither PATCO nor Reagan anticipated at the outset just how important a turning point in organized labor’s history their conflict would become. As the only former union leader ever to win election to the presidency, Reagan didn’t set out to provoke a confrontation with PATCO, one of the few unions that had endorsed him in 1980. Rather, he authorized his negotiators to offer more to PATCO than the government had ever given to a federal union during bargaining. Unfortunately, Reagan contributed to elevating unrealistic expectations among his former supporters. When they staged an illegal strike in protest of what they considered to be a low-ball offer, he gave them forty-eight hours to return to work. When the vast majority refused, he fired them. This move came as a relief to his conservative advisors who felt he had offered too much to the union to begin with.

Even Reagan’s harshest critics had to admit that he was acting within his powers under the law. Had Jimmy Carter still been president he might well have done the same. After all, Carter’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) had drawn up the strike contingency plan that Reagan’s people followed to break PATCO’s walkout. Reagan’s amendment to Carter’s plan was his refusal to rehire any strikers long after their union had been broken. That move burnished his reputation for toughness at the expense of the nation’s air traffic control system, which still suffers from the lingering effects of the mass firing.

It was his ability to pull off the dramatic, sudden erasure of 70 percent of a vital agency’s skilled workforce that proved most inspiring to private sector employers. In the 1980s, they sought to emulate Reagan. Many incited strikes by instituting draconian wage cuts just to have the opportunity to replace their strikers. For a decade, strike debacle after strike debacle played out for the copper miners of Phelps Dodge, the meatpackers of Hormel, the operatives at International Paper—causing many other workers to realize that they had lost the ability to strike effectively. This realization drove down the nation’s annual average of large work stoppages from 289 in the 1970s to thirty-five in the 1990s. That decline signaled a dramatic setback for bargaining power and opened the door to a new era of growing inequality that put us on the road to the present moment.

Still, compared to Trump, Reagan was a union sympathizer who respected the rule of law. Ironically, his decision not to rehire any PATCO strikers was largely intended to warn Moscow’s leaders that they had better not test his mettle, for if they did, he would show them no more mercy than he had shown controllers whose lives were shattered by being banned from the highly skilled profession for which they had spent years training. As heartless as that act was, Reagan never attempted to violate collective bargaining contracts in the federal sector, nor did he question federal workers’ legislated union rights. Indeed, his administration recognized a new air traffic controllers’ union at the FAA before he left office. The National Air Traffic Controllers Association exists to this day. And as mean-spirited as Reagan was in his denigration of government, with quips like “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help,’” such sentiments constituted rhetoric more than policy: the number of federal employees actually grew on his watch.

The contrast between the Reagan and Trump administrations are stark. Trump is pursuing his attack on federal workers’ rights through a “department” Congress neither created nor approved, Elon Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE). Musk’s minions have rummaged through some of the most sensitive private information the government possesses at agencies such as the Social Security Administration. When Democratic lawmaker Robert Garcia challenged Musk, Trump’s U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia raised the specter of investigating Garcia for making threats against a government employee. In the meantime, federal agencies have tossed aside collective bargaining agreements with their unions and run roughshod over civil service regulations in announcing mass layoffs and unilateral changes in remote work policies.

Trump has also outdone Reagan in his hostility to the key federal agencies charged with protecting workers’ rights: the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), and the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA). Reagan appointed staunch conservatives to those agencies—including naming Clarence Thomas as chair of the EEOC—and by doing so weakened their protective powers. But Reagan never claimed the right to fire Carter’s appointees in the middle of their terms of service. By contrast, Trump has removed duly appointed and Senate-confirmed members of each of these bodies, effectively disabling their function and seeking to ensure that henceforth such agencies will never act with any degree of independence. In the meantime, Musk’s SpaceX has joined with other employers to contest the constitutionality of the NLRB in federal court.

As the unprecedented attack on the NLRB and the EEOC already indicates, Trump’s current war on workers’ rights will not remain confined to the federal sector. Considering the speed, breadth, and radicalism of the current administration’s moves, its lasting impact is likely to be many orders of magnitude more harmful than anything Reagan did.

Trump can inflict more damage in part because U.S. workers are more vulnerable to a rollback of their rights today than they were in the 1980s. The potential bases of resistance have all been dramatically weakened over the past forty-four years. In relative terms, today’s union movement is less than half the size it was when Reagan broke PATCO. Unions are also more geographically isolated (a state like Alabama has seen union membership plummet from over 20 percent of its workforce to under 7 percent today). Our political system is far more polarized on labor issues now than it was in 1981 with only one party committed to upholding the last century’s accumulation of labor laws that were enacted with bipartisan support. A new class of multi-billionaires bends its knee to the far right. Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court, whose misguided ruling in Trump v. United States offered a broad cloak of immunity to the president, is more hostile to workers’ rights than any court in a century. The court’s tendency to slow-walk any decision that challenges Trump means that plenty of irreversible damage will likely ensue before it ever weighs in.

Where does this leave today’s labor movement and its allies? In answering that question, it is instructive to recall how labor responded to Reagan in 1981.

Organized labor was caught flat-footed by Reagan’s breaking of PATCO. The union neither sought nor received support from the AFL-CIO prior to launching its disastrous strike. AFL-CIO leaders were at a pre-scheduled meeting on August 3, 1981, when they heard that PATCO’s walkout had begun. They immediately worried about its potential impact on the entire movement. After all, the strike was an illegal action waged against a popular president who had been elected by a landslide and then earned bipartisan sympathy by having survived an assassination attempt six months earlier. At the same time, PATCO strikers seemed tone deaf. They were asking for large wage increases at a time when other unions were making concessions in their contract negotiations and taxpayers were staggering under the weight of stagflation. Union leaders knew that many workers, union or not, believed Reagan was right to give an ultimatum to the strikers.

Facing this situation labor leaders believed they could neither abandon their fellow unionists by condemning the walkout as a strategic blunder nor fully commit their organizations—many of whose members were divided on the issue—to a full-scale resistance to Reagan’s firing of the strikers. To be sure, AFL-CIO leaders marched on picket lines and their members participated in demonstrations at airports across the county. Sporadic acts of civil disobedience occurred in some places, but they were not organized by labor’s top leaders. Those leaders instead concentrated on organizing the massive Solidarity Day march on Washington, on September 19, 1981. It was the largest protest march that had yet been held in the capital’s history, but when the marchers went home afterward nothing had changed. Reagan had broken PATCO and the union movement could manage little more than to raise the chant that union busting was disgusting.

The psychological impact of that defeat on the labor movement and its opponents alike was profound. Labor’s inability to marshal significant resistance to the PATCO firings helped inspire business to bust unions with gusto in the 1980s. In some ways, the labor movement never fully recovered from that era of retreat.

Today’s labor movement and its allies face a similar moment of truth. At stake in Trump’s attack on federal workers and unions is more than the fate of one federal agency’s workforce, as was the case in 1981. At stake now is more even than the fate of all federal workers, or of American workers’ rights in the public or the private sector. At stake now is the very character of our government and the norms of democratic governance that have been constructed over decades. At stake now is whether we will have any labor movement at all to speak of ten years from now.

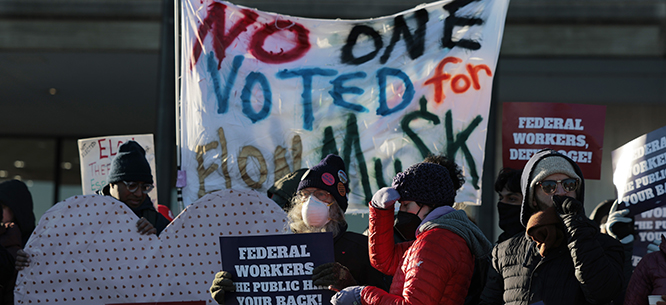

On February 19, I joined a rally organized by the Federal Unionists Network (FUN) outside the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as part of a national day of action. FUN—a grassroots network that includes union members from multiple unions across the federal service and around the country—is one of the most inspiring efforts to emerge over recent weeks. There were a thousand spirited protesters on hand, and they were clearly frustrated with Democratic leaders. When Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen told the rallygoers that he stood in solidarity with them, they interrupted him with cries of “Shut down the Senate!” When he concluded his remarks, they chanted “Do something!” I added my voice to their chant but, as I left, I was haunted by the recollection of many such gatherings that popped up in support of PATCO forty-four years ago to no avail.

As happened in 1981, today’s labor movement thus far appears unsure of how to respond to an emergency situation. In many ways, this is quite understandable. Few could have anticipated how fast this crisis would emerge and how dangerous it would quickly become. To this point labor is doing the things that are in its comfort zone: filing lawsuits, sponsoring rallies, and launching initiatives like the AFL-CIO’s “Department of People Who Work for a Living” to counter DOGE.

But labor and its allies can and must do much more. The conditions that inhibited unions in 1981 don’t exist now. Unions are riding a wave of popularity they have not seen since the days when Reagan was a Democrat. Unlike Reagan, Trump was not elected by a landslide, nor is he broadly popular. The public has none of the animosity toward federal workers today that many felt toward PATCO members, whom many saw as arrogant. While the public blamed controllers for flight delays, those whose federal contracts, grants, and services are being sacrificed amid these cutbacks have only Trump and Musk, a multi-billionaire who cares more about occupying Mars than addressing the concerns of everyday Americans, to blame. Public opinion is not clamoring for the complete dismantling of our government that is now underway. Perhaps most important, this time it is the president, not the workers he is targeting, who is breaking the law, and early public opinion polls reflect this realization.

These circumstances give labor and its allies, including non-federal workers, permission to escalate their tactics in a fight that must be waged not only for the future of the movement but for that of the nation as well. The context of this fight makes escalation possible; the enormous stakes make escalation necessary. What we are currently doing is simply not enough. Any escalation should of course be framed in ways that broaden support for the struggle to save our government and its workers from Musk’s chainsaw. But this is no time for sticking to our comfort zones.

Joseph A. McCartin is the director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, author of Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers and the Strike that Changed America, and president of the Labor and Working-Class History Association.