Noblesse Without Oblige

Noblesse Without Oblige

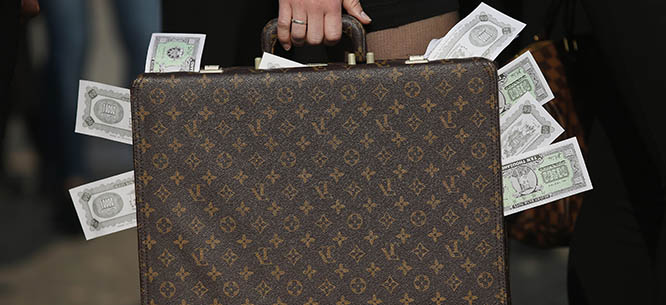

The super-rich opt out of the social contract by picking and choosing which laws apply to them, whether in offshore tax havens or at home.

Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism

by Brooke Harrington

W.W. Norton, 2024, 176 pp.

Over the past eight years, a series of major document leaks has shone a spotlight on tax havens and their users. The Panama Papers, made up of 11.5 million documents from the offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca, broke in 2016. Next came the Paradise Papers in 2017, a trove of even more material, mostly from the Bermuda-based law firm Appleby and two other offshore corporate services providers. The Pandora Papers, published in October 2021, constituted the largest and most comprehensive such leak yet. Several earlier, smaller leaks—including the Swiss Leaks in 2015 (from the Swiss subsidiary of the British multinational bank HSBC) and Lux Leaks in 2014 (detailing tax arrangements for multinationals devised by the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers and the Luxembourg government)—had garnered less publicity but likewise revealed the shameless activities of lawyers, accountants, bankers, and their clients.

Across the Panama, Paradise, and Pandora papers, a wide range of names popped up with offshore connections of one kind or another: popstars like Madonna, Bono, and Shakira; the former Prince Charles (now King Charles III) and the late Queen Elizabeth II; the former president of Colombia, Juan Manuel Santos; former UK prime minister Tony Blair; former Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta; Azerbaijan’s ruling Aliyev family; and Donald Trump’s onetime secretary of commerce Wilbur Ross, who held an interest in a shipping company that moved millions of dollars of Russian oil every year, with ties to Putin as well as other sanctioned individuals.

Given such wrongdoing among a sliver of extremely wealthy and influential individuals, why, after a couple of weeks of public attention, does the problem of tax evasion fade from view so quickly? In Offshore, Brooke Harrington, a sociologist at Dartmouth College, suggests an answer to this question. Part of the problem, she contends, is the culture of secrecy that pervades tax havens and other offshore jurisdictions. Most often, we simply forget that tax havens exist. This is not a bug but a feature of the system, designed by the politicians, lawmakers, and professionals who enable tax avoidance and evasion.

Harrington’s contention is that if these shenanigans of the super-rich were less shrouded in secrecy, people would be more outraged. That is probably true. Secrecy doesn’t just help rich people dodge the tax man, but also to keep the most unfair and unsettling aspects of widespread tax avoidance and evasion out of public view. Harrington cites recent findings by economic psychologists showing that most people vastly underestimate the extent of inequality in their countries—in the United States, by as much as 42 percent. Since the 1960s, offshore capitalism has quietly helped transform the global economy by pioneering financialization, facilitating elite impunity, and supporting the accumulation of ever greater intergenerational wealth, all while shielded from outside scrutiny.

Harrington’s book is the result of more than a decade of research. In 2016, she published Capital without Borders, a much-lauded analysis of the middlemen and enablers who help the super-rich protect their money from what is euphemistically termed “depletion”: inflation, currency devaluations, and, above all, taxes. These white-collar professionals often have backgrounds in banking, accounting, or law, and nowadays typically hold a certificate in wealth management. To study these enablers, Harrington enrolled in a two-year wealth management certification course and became one of them. She gained unique access to the secretive tribe of wealth managers and lawyers who create offshore trusts and register shell companies in which to park the assets of the rich beyond the reach of tax authorities.

Harrington’s latest book is more interested in the consequences of these activities, both in the home countries of the tax dodgers and the tax havens themselves. Some of the sharpest observations in Offshore concern the impact of offshore business on smaller countries, often former colonies and dependent territories that turned themselves into tax havens. Such societies might at first glance be expected to profit handsomely: the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg, for instance, are two of the wealthiest countries in the world by per capita income. But these rankings ignore distribution: Luxembourg’s aggregate wealth is divided unequally among wealthy expats, who make up the offshore industry, and Luxembourgers. The former have seen their salaries explode, tripling housing prices and driving up the cost of living in Luxembourg City. Ordinary Luxembourgers pay the price. Most tax havens are starkly unequal societies.

The secrecy essential to a successful tax haven also fosters a culture of lawlessness that affects the broader society. While wealth management in Geneva, London, and New York maintains a genteel façade, in former colonial outposts turned tax havens, this veneer of respectability is thin. When global elites elevate law-breaking to a way of life, impunity becomes a status symbol. In offshore jurisdictions, wealthy clients freely abuse the law to harass investigators, sometimes resorting to physical violence and criminality. Daphne Caruana Galizia, an investigative journalist who exposed criminal activities tied to offshore finance in Malta, was killed by a car bomb after she led local investigations of Maltese officials exposed in the Panama Papers. Her research revealed that both the country’s then prime minister and his political rivals were involved in money laundering; two of the prime minister’s close aides were later implicated in Galizia’s murder.

The island nation of Mauritius, east of Madagascar, is today an important tax haven for corporate investments flowing into Africa and India. Upon independence from Britain in 1968, the country’s economic future looked bleak; the Mauritian economy had for centuries relied on sugar cane cultivation, grown primarily by enslaved people. After independence, Mauritius expanded into tourism and textiles. The island’s first brush with offshore capitalism came in the form of a special economic zone (SEZ)—a space carved out of a wider territory where taxes, labor, and environmental regulations are rolled back to lure investors. (Today, the most famous such zones are sprinkled across the southeastern Chinese coast, where early SEZs such as Shenzhen were established as part of the country’s limited market experiments after 1978.)

In 1970, the Mauritian government turned the entire island into an SEZ, letting companies choose where to set up shop and allowing for duty-free imports of goods used to produce items for export. Exporters also received tax holidays and reduced rates for power, water, and building materials. The island’s economy boomed. The turn to offshore manufacturing came at a cost, of course: the companies that set up manufacturing enterprises on the island do not make significant contributions to employee pensions or other social security provisions, leaving workers with little to no safety net.

Many tax havens do not, in fact, offer very low or zero taxes to all taxpayers. Instead, they create legal carve outs for certain categories of individuals and companies. The principle of giving a special tax status to some taxpayers while maintaining ordinary taxation levels for others is as old as offshore capitalism itself. Later in the 1960s, this principle was cast into a readily identifiable corporate form called the International Business Company (IBC). Also known as “non-resident” or “exempt” companies, IBCs come in many varieties, but the general playbook is the same: create a special category of company that does not do business in the jurisdiction where it is registered and offer such businesses near-zero tax rates and often limited reporting and transparency requirements. For haven countries, it is a means of having your cake and eating it too: tax revenue can still be collected from local, domestically operating companies, while foreign companies and investors can be lured by exemptions and extremely low tax rates. British Treasury and Bank of England officials noted several Caribbean colonies’ introduction of IBC laws as early as 1968, including Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua, and St. Vincent. IBCs were thus not, as is often claimed, invented in the British Virgin Islands in the 1980s; it was simply that unlike prior laws in other places, the Virgin Islands’ new IBCs became an overnight hit. The real boom in IBCs began when countries in the region sought to emulate the success of the British Virgin Islands, where the number of companies registered grew rapidly after passage of the local IBC law. Other Caribbean nations adopted similar legislation in the 1980s and ’90s; Mauritius passed its own such law in 1992. These laws and companies are key to understanding how most tax havens really operate.

In Mauritius, too, the new law was an almost instant success. So much money from questionable sources flowed in that the country eventually made several international “worst tax havens” lists, including ones by the European Commission and Oxfam. “Shortly after,” Harrington writes, “several government officials were found to have welcomed drug trafficking money to Mauritius.” Lately Mauritius’s political system has entered a downward spiral, sliding, some argue, into authoritarianism. Recent prime ministers have exclusively come from a coterie of elite families; accusations of voter fraud are frequent. When peaceful protesters took to the streets in 2020–2021, the government deployed military police to crush dissent.

Harrington relates a startling episode that captures the island’s climate of impunity. “After warning me that crime was on the rise,” she writes, a local wealth manager “sent me off in a taxi, escorted by a minor government official who was to ensure my safety.” The taxi driver told her it was the anniversary of the murder of a female tourist and, when she mentioned her reason for being on Mauritius, said, “Government don’t want you here, won’t help you,” leading her escort to laugh. She then realized the two knew each other:

Within a few minutes, we were on an unlit two-lane road through sugarcane fields. . . . The taxi driver put his hand on my right thigh and squeezed. . . . My escort, sitting behind me, put his hand on my shoulder and fiddled with my bra strap . . . they kept talking to each other and laughing. . . . I’ll never know for sure what was in store for me that night, because I lucked out: lights unexpectedly appeared ahead of us on the otherwise dark, empty road. There had been an accident, creating a cluster of cars and a bit of traffic.

A third-generation sugar farmer told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (the group that has analyzed recent major offshore leaks) that the Mauritian government had abandoned the country’s native workers in favor of the financial services industry. As Harrington reports, the government also appears to have abandoned much of the law. Peddling impunity to wealthy tax-dodging elites risks conferring the same lawlessness onto politics and society at large.

In the Cook Islands, a remote archipelago in the South Pacific specializing in impenetrable family trust arrangements, Harrington’s hotel room was broken into while she was sleeping. A local fisherman complained to her that crime had risen along with the rise of offshore business: the country, he said, had become known as the Crook Islands. In the British Virgin Islands, a wealth manager whom Harrington had arranged to meet greeted her with chilling hostility and threats to have her deported. Within a few years, she writes, “the islands [had] descended into such corruption that an independent commission—headed by a retired British judge—was appointed to investigate BVI officials.” It produced a report that detailed officials’ involvement in drug and financial crimes as well as systematic intimidation of journalists and community leaders. “A year after the report was published,” Harrington writes, “the head of the BVI government, Premier Andrew Fahie, was revealed to be running a lucrative cocaine trafficking and money laundering operation.”

Tales of corruption and crime abound in offshore jurisdictions in the Global South. Yet Harrington carefully avoids stigmatizing them. After all, the worst tax haven in history is arguably Switzerland, very much part of the Global North; London, meanwhile, courts dirty money with high-end real estate that can be held through a combination of UK and anonymous offshore companies. In recent years wealthy individuals have discovered South Dakota and Nevada as high-secrecy jurisdictions that specialize in trusts, especially but not exclusively for non-Americans. Once, after I gave a talk at Princeton University, a history department faculty member declared during the Q&A that their family had set up a Nevada trust to “protect” their assets, explaining that this was for the benefit of their children (and therefore totally justifiable). They would likely be appalled to think of themselves as belonging to the same world as the corrupt political establishment of a place like the British Virgin Islands. But the proliferation of crime in offshore jurisdictions outside the Global North should be seen as simply the other side of an offshore capitalism that is always present—albeit, for most of us, hidden from view.

One reason for the prevalence of corruption and related crimes in offshore tax havens is that many such territories never had an opportunity to develop a healthy and stable civil society, social fabric, or political system. The establishment of offshore businesses in the Caribbean happened mostly while islands such as the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, and the Caymans were still under British rule; in fact, many tax havens forewent independence altogether, to benefit from the impression of stability and continuity that British dominion signaled to outsiders looking to park their money. White colonial elites in colonies-turned-tax-havens were often directly involved in registering companies and trusts and in passing the laws necessary to beef up the credentials of the emerging havens. In places that did pursue independence, such as Mauritius and the Seychelles, the turn to offshore capitalism occurred in moments of desperation, when, after gradually scaling down aid and other support, colonial overlords officially departed, leaving an economic, political, and social vacuum that was ripe for outside exploitation.

Panama is yet another tax haven plagued by extreme inequality. The World Bank estimates that some 25 percent of Panamanians lack basic sanitation, while 11 percent suffer from malnutrition. In wealthy parts of Panama City, glitzy skyscrapers host banks, accounting companies, and law firms catering to foreigners; on the other side of the tracks, Panamanians live in squalor. The city regularly claims a top spot on the list of the ten most violent cities in the world by per capita murder rate. While Panama was never formally colonized, its founding, in a split with Colombia, was promoted by American interests with an eye toward the construction of the Panama Canal. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, U.S. hegemony over Panama and control of the canal zone was so tight that contemporaries considered it a quasi-colony. Panama spearheaded the establishment of an open ship registry, turning the country into a tax haven for shipping. In the following decades, tax privileges for foreign-owned ships were extended to certain types of companies, thereby creating a full-fledged tax haven. As Harrington convincingly shows, countries such as Panama, as well as former colonies and overseas territories that have been turned into tax havens, sell impunity to foreigners while offloading the socioeconomic costs onto local populations.

Secrecy’s harmful effects are not limited to offshore tax havens but also extend to onshore societies. Harrington sees the super-rich “at home” as opting out of the social contract by picking and choosing which laws apply to them. The attitudes behind such behavior are much the same onshore and offshore; in the United States or Great Britain, it is simply better concealed and cushioned by a fraying but still existent social fabric. Freedom is the liberty to not be taxed: “noblesse without oblige,” as Harrington calls it. Meanwhile, the rest of us stand to become poorer as the tax base is eroded and government support for education, transportation, and health and housing services declines—public goods that the rich can to a certain extent choose to forego. As more than 300 economists put it in an open letter after the publication of the Panama Papers, there is simply no “useful economic purpose” for tax havens.

Vanessa Ogle is a historian at Yale University, where she teaches economic history and the history of capitalism. She is finishing a book on the history of offshore capitalism for Viking Books.