Tolkien Against the Grain

Tolkien Against the Grain

The Lord of the Rings is a book obsessed with ruins, bloodlines, and the divine right of aristocrats. Why are so many on the left able to love it?

With over 150 million copies sold, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is one of the best-selling prose narratives of the twentieth century and remains beloved by fans across the globe. The genre-defining story it tells of an unlikely provincial hero fated to save the world from destruction—and the close-knit, multi-species fellowship that aids him on his quest—has become the template for countless imitators in fantasy and science fiction, to say nothing of the series’ own adaptations into numerous popular films, television shows, and games.

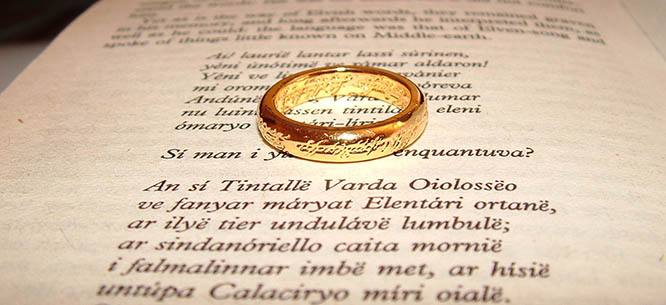

But if we judge Tolkien by those who claim his fellowship the loudest, we might grow concerned. Vice President JD Vance has said that not only is Tolkien his favorite author but that “a lot of my conservative worldview was influenced by Tolkien growing up.” And Vance has the receipts to prove it: he named his firm Narya after one of the three Elvish Rings of Power, just as Vance’s mentor Peter Thiel invoked Tolkien when naming Palantir Technologies, Mithril Capital Management, Lembas Capital, Valar Ventures, and Rivendell One LLC. In the 1970s the Italian right revitalized itself at “Hobbit camps,” a formative experience in the life of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who attended one of the camps as a teenager. Far-right and extremist groups in many other countries also revere Tolkien. The UK’s “Prevent” anti-terror program even recently characterized him (along with C.S. Lewis and George Orwell), somewhat preposterously, as a kind of gateway drug for potential radicalization.

Since the founding of the tiny corner of academia known as science fiction studies in the 1970s, there has been a sense that science fiction is of the left, while fantasy is of the right. Science fiction is about the future, about the utopias we might someday build, about science—while fantasy is about looking back toward an imaginary past of kings, empires, war, and magic (which is to say, nonsense). If science fiction is about revolution, fantasy is about restoration. Or so the Marxist critics who have championed science fiction and decried fantasy for the past half-century would have it. The fantasy work of some authors (like China Miéville, M. John Harrison, Michael Moorcock, or Ursula K. Le Guin, all writers who don’t fit neatly into any one genre category) are considered exceptions to this general tendency, but even when leftist fantasy is recognized, Tolkien himself nearly always stands as the bad example. In his 2005 Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, Fredric Jameson interprets Tolkien as the champion of a system of “reactionary nostalgia”; the climax of his most celebrated work, after all, is titled The Return of the King. (Tolkien considered The Lord of the Rings a single book, but it is typically published in three volumes.)

What is it about Tolkien’s work that supports this reading? The Lord of the Rings seems immersed in racism (the superiority of the fair and noble elves, the inferiority of the brutish, mongrel orcs), colonialism and imperialism (the return of the king means the restoration of empire), and deeply retrograde sexism (with a core cast of characters that is overwhelmingly male). There is also a generalized suspicion of democracy, cities, modernization, progress, cultural relativism, and materialism in favor of monarchism, agrarianism, stasis, fantasies of good versus evil, and a traditionalism that at times borders on religious fundamentalism (Tolkien himself was a pre–Vatican II Catholic). The Lord of the Rings is a series obsessed with ruins, bloodlines, the divine right of aristocrats, and a sense of history as a tragic, endless fall from grace.

Despite all this, Tolkien has many left-wing fans. They can point to his celebration of working-class heroes like Sam Gamgee over the more well-heeled and gentlemanly Frodo, his call for an ethics of selflessness and self-sacrifice, his rejection of the desire for power and control in favor of humility and communal society, and his absolute contempt for tyrants of all stripes. A chapter late in The Return of the King titled “The Scouring of the Shire” sees the four returning hobbit heroes throwing out the fascists who have taken over their homeland during their absence, using a mix of mockery, civil disobedience, pleasure activism, and strategic mass action (including, in the end, a violent uprising that leaves dozens of hobbits and men dead).

For the leftist critic who seeks to explain their fondness for The Lord of the Rings, however, most justifications come with a caveat. Perhaps the books’ depiction of a wartime esprit de corps, bringing people of different backgrounds together to achieve a common goal, can be likened to the solidarity needed for the hard work of changing the world. But this camaraderie cannot sustain itself beyond times of deep crisis—and, in any event, it’s typically predicated on a logic of shared, unrelenting racial hatred for orcs.

There is likewise a stirring ecological politics and love of nature in Tolkien. Gardeners of varying sorts turn out to be the ultimate key to human thriving. But Tolkien’s is a deeply tragic environmentalism, largely impossible to separate from the elves’ doomed desire to freeze time in a world that has begun to move beyond them. The hobbits’ Shire provides the glimmers of a model for some third way between capitalism and communism, two systems that Tolkien found equally repugnant—yet the hobbits cannot sustain their paradise through the conclusion of the book without magical assistance, and the evidence suggests that in the end their world is brutally destroyed in favor of our own.

Finally, there is some beautiful antiwar sentiment in Tolkien’s work, a rejection of war’s glories and a refusal to celebrate its violence—but this goes hand-in-hand with a compromised pacifism, set aside when the moment demands the heroes take up the sword. The central protagonist of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo, spends much of the end of the book begging people to stop hurting each other, and he never gets what he wants.

I have read The Lord of the Rings many times since I first encountered it in elementary school; in my twenties I even was fired from a job for reading the book when I was supposed to be working (not to brag). Now, I lead a Tolkien class at least every two years; Marquette University, where I teach, has the improbable privilege of being the home of much of Tolkien’s papers, including the drafts of both The Lord of the Rings and its predecessor The Hobbit, and I have been lucky enough to use this archive in the classroom.

Through all this rereading and archival exploration, I have come to understand just how strongly The Lord of the Rings encourages a dialectical approach, where we seize on moments of internal contradiction to read the book against the grain. The work of Robert T. Tally Jr.—who, like me, was a student of Jameson, and who still likes Tolkien despite the unambiguous word of the master—is exemplary of this strategy. Tally excavates the text for signs that the decline of the elves might not be so bad after all, or even that the orcs have the better part of the argument. In the rare moments where we see the orcs unguarded, they too express longing for an end to war, despising the dark lord Sauron who commands them and his hideous Nazgûl shock troops. It is Sam’s unexpected pity for a human who is nominally his enemy that has rightly become one of the most often-quoted passages from the book: “He wondered what the man’s name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace.” Part of what has sustained interest in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings for the last eighty-seven years are precisely these sorts of rough edges and unfinished thoughts.

For me, however, the key is the books’ frame narrative. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings present themselves not as novels but as historical documents, uncovered by some anonymous scholar and presented to the twentieth century as an unknown story of the very deep past. The story of The Lord of the Rings comes from a copy of a copy of a many-thousands-of-years-old volume called The Red Book of Westmarch, ostensibly written by the saga’s main characters after the fact and annotated, corrected, and expanded by various parties later on. These origins can be seen in the book’s strange and ponderous foreword, along with its more than 100 pages of pseudo-scholarly appendices.

While the movies and video games based on the book erase this frame, and many first-time readers ignore it entirely, it was integral to the work Tolkien understood himself to be doing, and it invites a reading strategy that is not about established and unimpeachable facts but rather a deeply contested historical narrative based on extremely incomplete records and a long and polarized debate. The prose of The Lord of the Rings unwinds in places like the appendices, ceasing to be a fairy tale and instead becoming a self-reflective commentary on what, how, and why we remember.

Perhaps it is a hazard of the scholarly career that Tolkien and I share—before he was the world’s premier fantasy novelist, he was best known as a scholar of Beowulf—but when I read The Lord of the Rings now I find myself drawn more and more to the fierce struggle over historicization that we see happening at the margins of this odd document, the sense built into the novel that there may be other Red Books, other legendariums, than the one we currently possess. The reactionary fantasy of a battle between the forces of absolute good and absolute evil, in which good triumphed and evil was defeated, cannot be sustained even within the novel’s 1,000 pages. Instead, The Lord of the Rings gives us a self-undermining critical apparatus that repeatedly undercuts the main text and asks us to pay attention to silences, gaps, and omissions; to distrust the narrator; and to dig into contradictions. “Always historicize,” Jameson once said. In its own strange and deeply uneven way, The Lord of the Rings says much the same thing.

When my students are unhappy about the final fate of Éowyn, the proto-feminist warrior-maiden who describes gender normativity as a cage and who says she would rather die than have to live out her life according to patriarchy’s script, only to wind up married off anyway, I point out that the appendices record people still arguing about Éowyn and what the story of her life means, centuries after the fact. It is the appendices that tell us that the restored King Aragorn never stopped waging wars, that his queen died miserable and mad with grief. These moments of textual uncertainty are visible across the main text as well: passages that suddenly leap decades or even centuries into the future, that break narrative perspective, that provoke questions about the reality of the saga that the narrator cannot explain or that describe events that no one actually witnesses but are nonetheless presented as inarguable historical facts.

It is the ultimate ambiguity and indecision of the text that explains not only why Tolkien has endured but why so many on the left are still able to love him, despite all the many perfectly persuasive reasons why they shouldn’t. There is always another loose thread to pull on, another unexpected possibility to consider—alongside the dreaded possibility that Vance and his ilk are right about Tolkien, the possibility that Tally and I are, too. The book itself cannot choose; its own characters spend the next century trying to figure out just what the War of the Ring actually meant. It is in these moments of textual flux that I find this oddly enduring work remains most provocative, most unsettled, most interesting, and most alive.

Gerry Canavan is chair of the English department at Marquette University and the author of Octavia E. Butler.