A Demonstration of Working-Class Power

A Demonstration of Working-Class Power

Labor Day was the first national holiday that a social movement both created and persuaded the state and businesses to honor.

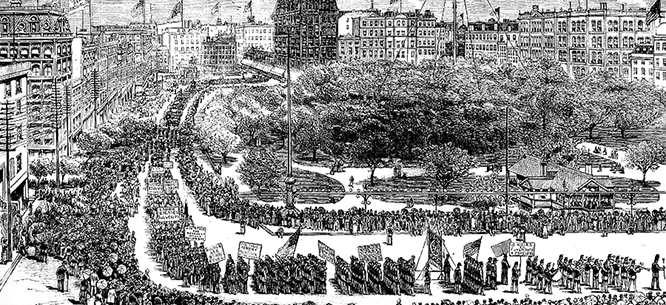

Labor Day began as a demonstration of working-class power. On September 5, 1882, the Central Labor Union of New York City planned a parade around Union Square in Manhattan, followed up by a lavish picnic. The CLU—an umbrella body led by socialists—was determined to “show the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and Labor organizations” of the biggest city in the United States and to “warn politicians that they shall go no farther in pandering to the greed of monopoly and reducing the condition of the masses.”

The thousands of people who came to march and play that day certainly made their intent clear. Over the next decade, workers in numerous other cities followed their lead. In 1894, a Congress that was hoping to mollify wage earners during a time of economic depression and a nationwide railroad strike passed a law making Labor Day a national holiday. But private employers were under no obligation to give their workers the day off. So in many towns and cities around the country, Labor Day became a virtual one-day general strike. Workers stayed off the job and dared their bosses to fire them. Not until the early twentieth century did most businesses reluctantly observe the occasion.

For decades to come, union members filled the streets and parks of their cities, supportive politicians announced their support for the labor movement, and the press described the floats, banners, music, costumes, and speeches in great detail. In Los Angeles during the late 1930s, movie stars who belonged to the Screen Actors Guild stood on floats with banners that read, “Don’t Let Them Muzzle Labor” and “Keep Labor Free.” At the 1937 parade, wrote historian Lary May, an actor dressed as Abe Lincoln proclaimed that workers of all races deserved to enjoy the fruits of their labor, while “Popeye and the Keystone Cops chased away ‘scabs.’”

There was a unique quality to Labor Day that set it apart from more universal, largely apolitical celebrations like Thanksgiving. Until the first observance of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, Labor Day was the only national holiday that a social movement both created and persuaded the state and businesses to honor.

So take to the streets or spread out your picnic blanket and sing some of these great labor songs.

Michael Kazin is an editor emeritus of Dissent. His most recent book is What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party.