The Rise of the Elite Anti-Intellectual

The Rise of the Elite Anti-Intellectual

For decades, “common sense” has been a convenient framing for conservative ideas. The label hides a more complicated picture.

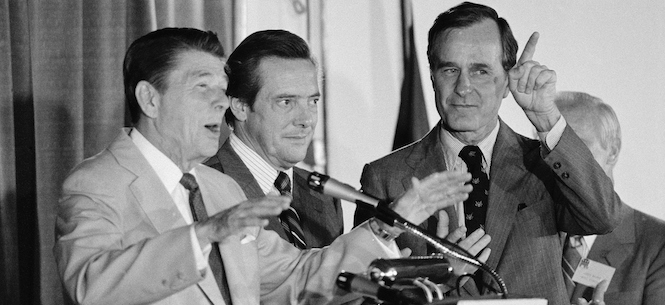

In 1978, Bill Brock founded the “almost scholarly” journal Common Sense under the auspices of the Republican National Committee, which he chaired. The journal gathered together young political operatives and sympathetic social scientists to issue conservative policy proposals. Two years later, as Ronald Reagan prepared to enter the White House, Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan pointed to Common Sense as proof that the Republicans had successfully established themselves as the “party of ideas.”

For decades, “common sense” has been a convenient framing for conservative ideas, in contrast to the dangerous and alien notions favored by a liberal intellectual elite. The label hides a more complicated picture. While conservative intellectuals present their ideas as straightforward and natural, they hold onto the trappings of erudition—and maintain a specific canon—in their own counter-institutions. Higher education, they believe, should remain an exclusive undertaking.

Conservative hostility to perceived academic trends is being put to new use as Republicans pursue state and federal legislation that targets teaching they associate with “critical race theory” (the Claremont Institute has devoted a number of essays to the topic). Most of the proposals that have gained traction at the state level are focused on high school education. But in March, Arkansas Republican Senator Tom Cotton introduced legislation to ban any teaching of critical race theory in the U.S. military.

The legislation to restrict subjects from classrooms joins a raft of proposals designed to attack universities and their financial basis more broadly. Cotton has drafted legislation to tax the endowments of private universities—except those with a “religious mission”—and distribute the revenue to vocational training programs. He frames the tax as a penalty for “indoctrinating our youth with un-American ideas.” In Florida, meanwhile, Republican senators advanced a bill that would transfer scholarship funds toward only those university degree programs that lead directly to employment.

In his recent book The Rise of Common-Sense Conservatism, historian Antti Lepistö provides some crucial backstory for how conservative intellectuals came to claim the mantle of popular opinion against an allegedly hostile intelligentsia. Starting in the 1970s, neoconservatives began to formulate arguments based on the authority of common sense. In the pages of publications like The Public Interest, writers like Irving Kristol and Gertrude Himmelfarb turned from social science to moral philosophy to celebrate the intuitions of the “common man” against the bureaucrats behind the social programs of the Great Society.

This was not a natural move for self-identified conservatives, who inherited a tradition skeptical of untutored popular democracy. To justify common sense, Kristol and Himmelfarb turned to philosophers like Adam Smith and David Hume, refashioning theories of moral psychology descended from the Scottish Enlightenment to advance their critiques of contemporary social policy and the welfare state. These eighteenth-century thinkers had developed a system to explain how everyday moral intuitions fit within and even sustained the commercial exchanges of an emerging capitalist economy. In essays like “Adam Smith and the Spirit of Capitalism” (1976), Kristol presented these arguments about common sense morals and free commerce to a readership growing hostile toward liberal social engineering.

The neocons soon directed their ire against intellectuals writ large. In essays like Kristol’s “Adversary Culture of Intellectuals” (1979), college professors and policy analysts came under attack as hopelessly detached from the students they taught and the public they served. In a later essay, Kristol made it “the self-imposed assignment of neoconservatism” to “explain to the American people why they are right, and to the intellectuals why they are wrong.”

A legacy of these efforts can be seen in numerous summer schools, fellowship programs, and think tanks on the right that teach a curriculum of canonical texts, often with the intent of countering what they perceive as a threatening leftist consensus in universities. Some of these, like the “Publius Fellowship” for advanced college students and recent graduates at the Claremont Institute, and the libertarian Mercatus Center at George Mason University, which now funds “Adam Smith Fellowships” for graduate students, were founded in the late 1970s and early ’80s as conservatives took the reins of political power. Others started more recently; the Christian conservative John Jay Institute began teaching constitutional and theological texts to its graduate fellows in 2005, and the Hertog Foundation established Political Studies and War Studies programs for college students in 2010 and 2013.

These programs represent distinct strands of right-wing thought. The Mercatus Center trains students in the classical liberal thought of Adam Smith and the later “Austrian, Virginia and Bloomington schools of political economy” with the goal of shaping future teaching and scholarship. While the Claremont Institute explicitly seeks “a selective group of promising young conservatives,” the Hertog program in Political Studies makes no direct statement of an ideological commitment, beyond a focus on the “big ideas” behind policy. (Prominent displays of the writings of Edmund Burke in their promotional video and a speaker series that includes Tom Cotton make its orientation clear enough.)

Despite these distinctions, these programs share a model of political education: to train small numbers of young people entering politics, journalism, law, and the military in conservative ideas.

This model doesn’t stop the Claremont Institute and its fellows from railing against academics and their theories, however. Theirs is an elite critique of the intellectual establishment. (In Democracy and Truth, Sophia Rosenfeld traces this tradition back to the eighteenth century, when Burke lamented how “sophisters, economists, and calculators” had taken public authority from the chivalrous nobility.) This elite yet anti-intellectual dynamic was on display at the conference of the Edmund Burke Foundation two summers ago, when Missouri Senator Josh Hawley delivered a keynote address that lambasted “the nation’s leading academics” for their “cosmopolitan consensus” against patriotic education. This consensus, he explains, presses down against “common affections and common loves,” and it denigrates the “common culture left to us by our forebears.” The conference, and Hawley’s speech in particular, were covered by critics from the left and hesitant supporters of the established right as the articulation of a new intellectual movement around Trumpian politics.

Hawley’s own education (BA from Stanford, JD from Yale) is anything but common. From his bully pulpit, however, he decries academics and universities as he seeks to drain them of financial support. In 2019, Hawley proposed a bill that would allow students to use Pell Grants at more private apprenticeship and job-training programs—for the stated purpose of starving the “higher education monopoly.” A companion bill would compel universities to pay back some of their students’ debt upon default. Debt-financed four-year college is, for Hawley, the siren song of the meritocracy, convincing working people that they ought to go to universities to better their lot in life. The best thing for them, he argues, isn’t to make college free, as many on the left have proposed, but to find alternatives in direct, and often private, vocational training. In 2020 Hawley wrote a bill limiting federal COVID-19 relief for universities with endowments larger than $10 billion, setting an example that Cotton expanded in his plan to tax private university endowments. Another Yale-educated self-styled populist, J.D. Vance, has also suggested that universities and other foundations lose tax exemption on account that they “teach literal racism to our children in their schools.”

When the sentiments that bind citizens together are “common,” no education beyond vocational training is a public asset. The practical solution that Republican politicians offer against the malign influence of critical race theory at the universities is to simply defund that education and redirect resources elsewhere.

Hawley’s political prospects have seriously dimmed since January 6, but conservatives who speak the same pedantic language, warning of the dangers of leftist ideas in the academy, are gaining a more prominent profile. Christopher Rufo, the architect of the right-wing reaction against critical race theory, trades in meandering genealogies of its Marxist origins. His career has also been propelled through conservative counter-institutions like the Claremont Institute.

Some liberals recognize this importance of a canon to conservatives and want to emulate it. Molly Worthen, writing on the eve of Trump’s inauguration, insisted that after an “anti-ideological election” it was imperative for liberals to learn from the conservative summer schools and rediscover their canon. They could find common ground by recovering their debts to Smith, Burke, and other luminaries they shared with conservatives.

Socialists have good reason to embrace the robust political education in foundational ideas that conservatives have prioritized for decades, with alterations. The focus and structure of right-wing programs is bound by an ideological commitment to train future leaders. The long tradition of socialist book clubs that combine classic and contemporary texts offers an alternative model for internal political education.

At a broader level, socialists can learn from right-wing policy efforts: public university education is, in fact, a threat to conservative aspirations. As the political theorist Danielle Allen has shown, higher education corresponds to a greater degree of civic participation. Empowering working people by dismantling the financial barriers and debt burdens that keep them from that education is not just an extension of democracy, but part of a sound political strategy.

Simon Brown is a doctoral candidate in history at UC Berkeley and edits the Blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas.