A Women’s Strike Reader

A Women’s Strike Reader

In support of the International Women’s Strike on March 8th—a day of action planned by women in more than fifty different countries—Dissent presents a series of socialist feminist highlights from our archives.

In support of the International Women’s Strike on March 8—a day of action planned by women in more than fifty different countries—Dissent presents a series of socialist feminist highlights from our archives.

Sarah Jaffe, “Trickle-Down Feminism” (2013)“While we debate the travails of some of the world’s most privileged women, most women are up against the wall. According to the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, women make up just under half of the national workforce, but about 60 percent of the minimum-wage workforce and 73 percent of tipped workers. In the New York area, a full 95 percent of domestic workers are female. Female-dominated sectors such as retail sales, food service, and home health care are some of the fastest-growing fields in the new economy, and even in those fields, women earn less; women in the restaurant industry earn 83 cents to a man’s dollar.

This is where most women spend their time, not atop the Googleplex. This is where feminists should be spending their time, too.”

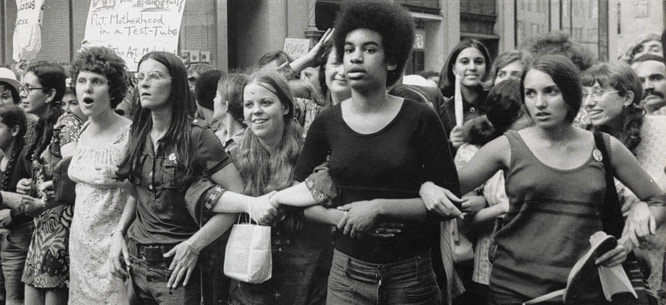

Laura Tanenbaum and Mark Engler, “Feminist Organizing After the Women’s March: Lessons from the Second Wave” (2017)“Many progressives are rightly dismayed at what Trump’s presidency might suggest about the persistence of sexism fifty years after the emergence of the women’s liberation movement. What will be significant in facing the horrors of the Trump administration will be whether this dismay can be channeled into a revitalized grassroots movement to confront the sexism and racism that Trump embodies, the newly emboldened threat to reproductive rights, and the coming attacks on the social safety net.

The fact that upwards of 500,000 people attended the Women’s March on Washington, which took place the weekend after Trump’s inauguration—and that some 3 million more participated in parallel marches throughout the country—suggests that such a movement can find a energetic base of support.

Those organizing this base should draw lessons from the upheaval of fifty years ago—the history of which is too little known, even among progressives. Looking back at this period of revolt, we can ask: How did it erupt? Why did it end? And what did it accomplish?”

Kaavya Asoka and Marcia Chatelain, “Women and Black Lives Matter” (2015)“Black Lives Matter is feminist in its interrogation of state power and its critique of structural inequality. It is also forcing a conversation about gender and racial politics that we need to have—women at the forefront of this movement are articulating that ‘black lives’ does not only mean men’s lives or cisgender lives or respectable lives or the lives that are legitimated by state power or privilege.”

Anne Phillips, “Sexual Equality & Socialism” (1997)“What has socialism to do with sexual equality? Can equality be achieved simply through recognition of the equal worth of all individuals, regardless of their sex? Or is socialism—and if so, what kind of socialism—a necessary condition for true equality between the sexes?

Differences and inequalities have to be detached from the accident of being born male or female, so that the choices we make and the inequalities we condone reflect individual, rather than sexual, variation. It was the liberal tradition that first gave voice to this ideal, but it is socialism that could make it reality.”

Tressie McMillan Cottom, “Trickle-Down Feminism, Revisited” (2016)“Much like the economic ideology that generating wealth for a few will trickle down to improve the relative prosperity of the many, trickle-down feminism assumes that better options for elite white women will trickle down to the rest of us. Anne-Marie Slaughter says as much, arguing that caring about the well-being of elite women means elevating powerful women who will take care of the interests of less powerful women.

There is no more persistent debate in feminist theory and praxis than ones about inclusion. . . . All versions of the have-it-all thesis are susceptible to the same critiques because the thesis is just a manifestation of capital’s creative translation of our precarious, post-work political economy. At its heart, for some women to have it all, most women cannot ever have enough.”

Sarah Leonard and Nancy Fraser, “Capitalism’s Crisis of Care” (2016)“There’s a tremendous amount of organizing and activism going on, a lot of creativity, a lot of energy. But it remains rather dispersed and doesn’t rise to the level of a counter-hegemonic project to change the organization of social reproduction. If you put together struggles for a shorter work week, for an unconditional basic income, for public child care, for the rights of migrant domestic workers and workers who do care work in for-profit nursing homes, hospitals, child care centers—then add struggles over clean water, housing, and environmental degradation, especially in the global South—what it adds up to, in my opinion, is a demand for some new way of organizing social reproduction.”

J.C. Pan, “Love’s Labor Earned” (2017)“While simply putting a pro-women gloss on an economic crisis does nothing to end that crisis, there does exist a different kind of feminist demand for compensated caring that could help point a way forward. Wages for Housework, the 1970s international Marxist feminist movement, sought to unmask how women’s unwaged reproductive labor in the home provided the basis upon which capitalism subsisted. Tending to men’s emotions free of charge very much figured into this scheme: Silvia Federici, one of the founders of the movement, wrote in 1975, ‘To say that we want wages for housework is to expose the fact that housework is already money for capital, that capital has made and makes money out of our cooking, smiling, fucking.'”

Ellen Willis, “Feminism Without Freedom” (1991)“During the earliest skirmishes between the women’s liberation movement and its New Left progenitors, one of the charges that flew our way, along with ‘man-hater’ and ‘lesbian,’ was ‘bourgeois individualist.’ Ever since, left criticism of the movement has focused on one or another version of the argument that feminism (at least in its present forms) is merely an extension of liberal individualism and that, largely for this reason, it is a movement of, by, and for white upper–middle-class career women.”

Barbara Ehrenreich, “Feminism and Class Consolidation” (1989)

“While some women moved into positions of visibility and even power, the average working woman, who is not a professional and not likely to be college-educated, is still pretty much where she always was: waiting on tables, emptying wastebaskets, or pounding a keyboard for five or six dollars an hour. If the recent opening up of the professions has been feminism’s greatest victory, it is a victory whose sweetness the majority of American women will never taste.”

Madeleine Schwartz, “Less Work, More Time” (2015)“Since the second wave, much of feminism has upheld waged work and work outside the home as a way for women to find independence and freedom. Mainstream feminists have often praised the workplace as the site of great gains for women and encouraged women to work and better the conditions of their workplaces through activism, professional organizations, and legal campaigns. These efforts have improved the lives of many women by offering them economic stability and opportunities once only open to men.

But waged work is itself constricting and demanding—hardly liberation itself. As women have entered the workplace, the kinds of jobs they take have often declined in quality, paying less, demanding more, and becoming more unstable and restricting. Work does not foster independence or freedom when individuals cannot choose where they work or the conditions under which they do so. Placing work at the core of a feminist demand obscures work’s problems and blinds us to life outside of it.”

Ann Snitow, “Returning to the Well: Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex Reissued” (1994)“The dynamism of Marxism, the flowing sixties atmosphere, and the general tendency of feminist utopians to dream of amniotic bliss—all meet in The Dialectic of Sex. . . . When one remembers that the feminist bookshelf wasn’t a foot long in 1970, the fullness, clarity and force of Shulamith Firestone’s feminism is simply amazing.”

Katha Pollitt and Dorothy Roberts debate the place of reproductive rights in the feminist movement (2015):Katha Pollitt, “Reclaiming Abortion Rights”

“How can the reproductive rights movement start to win again? ‘Start’ is the operative word. We’re getting crushed out there.”

Dorothy Roberts, “Reproductive Justice, Not Just Rights”

“The language of choice has proved useless for claiming public resources that most women need in order to maintain control over their bodies and their lives.”

Michelle Chen, Invisible Immigrants: What Will Immigration Reform Mean for Migrant Women? (2013)

“At a time when more American women are asking why they ‘can’t have it all,’ immigrant women endure a much crueler work-life balance: mostly poor, often without papers, and largely Latina, they’re exposed daily to chronic poverty, the threat of deportation, and sexual trauma. The struggle is inscribed on their bodies and reproductive destinies.

‘Immigrant women in Texas tell us that accessing birth control, cervical cancer screenings, and other reproductive care is so difficult here in the United States, they’re forced to cross into Mexico in order to get the care they need,’ says Kimberly Inez McGuire of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health. ‘One woman told us about how she literally swam across the Rio Grande to get access to reproductive care.'”

Katie J.M. Baker, “Cockblocked by Redistribution: A Pick-up Artist in Denmark” (2013)“What’s blocking the pussy flow in Denmark? The country’s excellent social welfare services. Really.”

JOMO, “Caring on Stolen Time: A Nursing Home Diary” (2013)“Our infantilization by the bosses is only a reflection of the way the elderly and people with disabilities are treated. Genuine support for the elderly and thoroughness of care that respects their self-determination would require more labor-time, labor that the bosses are unwilling to pay for, and in many cases the resident’s own families couldn’t afford because their own wages are not high enough. The ticking time clock and the money-saving blueprints don’t allow for human agency or rhythm. . . . We nursing assistants run on stolen time.”

Sarah Jaffe and Michelle Chen, “Belabored Podcast #62: The Unfinished History of Labor Feminism” (2014)“The feminist movement has always been multiple feminist movements, and many feminists did their work within and through other social movements like labor and the civil rights movement.”

From our friends:Magally A. Miranda Alcazar and Kate D. Griffiths, “Striking on International Women’s Day Is Not a Privilege” (The Nation)

“Strategizing for the future requires confronting the past. We must understand that the figure of the “stay-at-home wife” or the secretary, popular feminist symbols of women’s oppression, by no means represent the entire experience of women’s work. On the contrary, for most of US history, the bulk of social reproduction has been carried out by indentured servants or slaves, free black and poor white women, and, more recently, poorly compensated and often abused immigrant women. Seen from this vantage point, our diversity is an asset with which to build a women’s movement with a multi-issue platform.”

Dayna Tortorici, “While the Iron Is Hot” (n+1)“Wage inequality is sexist discrimination, compounded for many of us by other forms of discrimination: against race, religion, sexuality, legal status. Why do employers pay women less money than men? Because they can. Why do women tolerate it? Because we’re accustomed to losing. The strike is an opportunity to collectively refuse what some would choose to see as inevitable.”

Get Your Strike On (The New Inquiry)How to strike? Eight proposals from International Women’s Strike, NYC.