Fast Change and Its Discontents

Fast Change and Its Discontents

Jeffrey Wasserstrom introduces a special section on China in the Spring 2013 issue: “Wherever this protean country moves next, it will be taken there not just by people whose names are widely known but by those whose dreams, desires, aspirations, and actions make up China’s 99 percent.”

This special section offers a behind-the-headlines view of China that focuses on how some of the groups and individuals that make up the country’s laobaixing (roughly, “the 99 percent”) have been living through and shaping complex and challenging times. The authors, who have a deep understanding of life on the ground in today’s China, steer clear of discussion of the famous figures whose views and actions often dominate daily news coverage of China. In doing so, they illustrate the flaws in two influential visions of Chinese politics that have, each in its own way, distorted American thinking about China ever since June 4, 1989, the momentous day that saw both a massacre of protesters and by-standers near Tiananmen Square and the first electoral victory in Poland of Solidarity.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, a few short months after state violence curtailed the Tiananmen protests, and then the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Western observers began to assume that the Chinese Communist Party is living on borrowed time and will topple or implode any day now. Surely, according to this conventional wisdom, which is spelled out in high-profile books with titles such as China’s Democratic Future and The Coming Collapse of China, the Beijing regime cannot endure.

What these observers miss in their expectation of inevitable democratization or implosion is the obvious readiness of post-Tiananmen Chinese leaders to do whatever it takes to ensure the survival of the Communist Party. They have capitalized on the considerable resources at their disposal, including the goodwill associated with the role that the Communist Party had played in helping free China from foreign bullying before 1949. In addition, they have made careful study of all the factors that have contributed to the fall of other communist governments with an eye to avoiding the “Leninist extinction” of 1989 and its aftermath.

Since the early nineties, the Chinese authorities have displayed a sophisticated strategy for staying in control. They ratcheted up patriotic education campaigns that emphasized the Communist Party’s role in fighting imperialism. Haunted by the example of Solidarity, they moved swiftly and harshly against any organization that seemed capable of connecting people across class lines and geographical borders, while often taking a relatively lenient line on protests that involved only isolated groups and local issues.

Since the early nineties, the Chinese authorities have displayed a sophisticated strategy for staying in control.

Equally important, they worked to minimize some of the specific grievances that had fueled the massive protests of 1989. Students were frustrated by the state’s micromanaging of their private lives, so the Communist Party has been less controlling of what people say and do in their homes. Many were angered by the fact that the economic reforms only materially improved the lot of a small segment of society, so the authorities made it possible for a broader swath of people to enjoy at least some fruits of the boom times. If you let us stay in power, their new bargain proposed, we will give you more choices about how you make and spend money and what you do in your leisure time.

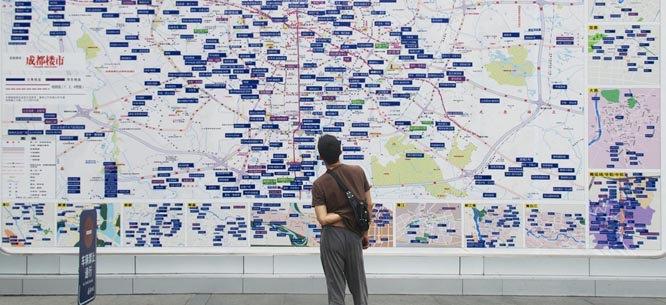

(Photographer Tong Lam, whose work appears on the opposite page, has been documenting the often curious directions in which this consumerist turn has been taking China. For more examples, see his online photo essay, available soon at dissentmagazine.org.)

This strategy worked well—so well that it gave rise to another conventional wisdom that hides important underlying issues. In this case, observers overstate rather than underestimate the strength of the Chinese Communist Party. In recent years, the organization has seemed to be on such a roll that it looks to some as if China may displace the United States as the most powerful nation on earth.

This second influential but misleading view is reflected in such new, high-profile works as When China Rules the World and The Beijing Consensus. These predictions mislead by minimizing the enormous challenges the Chinese Communist Party continues to face.

Given the incredible diversity of China, the strategy of rule sketched out above has never worked for everyone or applied equally to all parts of the country. Many Chinese in rural areas have been frustrated by how long it has taken for the rising tide that was supposed to lift all boats to reach them, and large numbers of members of ethnic groups, most famously Tibetan and Uighurs, have never accepted the mythic notion that in 1949 the Communist Party, whose leaders treated them much like colonized subjects, had gloriously “liberated” all citizens of the People’s Republic of China from foreign control. A third key grievance driving the protests of 1989—anger at corruption and nepotism—has never gone away.

Many who have been doing relatively well materially in recent years are now questioning whether their quality of life really is improving. They hunger for a government they can trust.

Most recently, an additional challenge has emerged: discontent among many of those who once seemed most ready to accept the post-1989 consumerist bargain, as long as it meant that life kept improving materially. After a series of tainted-food scandals and an ongoing pollution crisis, epitomized by the wretched smog that blanketed many cities this past winter, many who have been doing relatively well materially in recent years are now questioning whether their quality of life really is improving. They hunger for a government they can trust.

How can we move beyond the tendency either to underestimate the resilience of the Chinese Communist Party or fail to understand the important challenges it faces? Helen Gao, Leta Hong Fincher, Alec Ash, and Ross Perlin show us a valuable way to proceed, charting out an alternative path of analysis that will also be explored in later contributions to Dissent, which is committed to publishing similar behind-the-headlines reportage and analysis on China in future issues. These four deeply informed writers pay attention to the attitudes of ordinary people; to individuals who are neither part of the government nor locked into a directly antagonistic relationship to the regime; to women as well as men; to the young as well as the old, keeping in mind that for two thirds of China’s 1.3 billion inhabitants, Chairman Mao has always been dead.

Each author encourages Dissent’s readers to be skeptical of any straightforward response to broad queries such as whether the lives of “the people of the People’s Republic” are getting better or worse. They encourage us to doubt both the optimistic responses to this question that fill official Chinese Communist Party propaganda, which cannot be squared with the self-immolations in Tibet and other recent tragedies, and the starkly pessimistic ones offered up by the harshest detractors of the Beijing regime, who sometimes imply that it is impossible to speak of anything having changed in China as long as Mao Zedong’s portrait looks down on Tiananmen Square. And they push readers to break all big questions about “the Chinese” into smaller questions that take into account the complex diversity of China.

Regional differences clearly matter in today’s China. This is a theme that Gao’s discussion of con-temporary Chinese nationalism addresses as it moves between the very different worlds of mainland cities and Hong Kong, the former Crown Colony that is now a specially administered district of the People’s Republic of China.

Women and men have been affected differently by recent economic and cultural trends. Hong Fincher’s contribution makes this clear with its discussion of the post-Mao retreat from concern with gender equality.

Generational differences are crucial as well. As Ash reminds us, in a country changing as fast as China, the cultural distance between twenty-somethings and forty-somethings can seem more like a chasm than a gap.

The Communist Party once pledged to do away with the division between haves and have nots, but the country it governs is one where disparities of wealth and poverty are growing at a staggering rate.

In addition, class clearly still matters. The Communist Party once pledged to do away with the division between haves and have nots, but the country it governs is one where disparities of wealth and poverty are growing at a staggering rate, and where, as Perlin’s article underscores, workers, who were promised that they would be “masters” of the New China, remain anything but.

Where is China heading? None of the contributors, myself included, has a grand prediction to offer to substitute for titles that speak of the country collapsing or ruling the world. We share a conviction, though, that wherever this protean country moves next, it will be taken there not just by people whose names are widely known but by those whose dreams, desires, aspirations, and actions make up China’s 99 percent.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at UC Irvine and a regular contributor to newspapers, magazines, blogs, and journals of opinion. He is the author of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2010), an updated edition of which will appear in June, and co-editor (with Angilee Shah) of Chinese Characters: Profiles of Fast-Changing Lives in a Fast-Changing Land (University of California Press, 2012).