Love in the Time of Privatization

Love in the Time of Privatization

“Social relationships mirror wage relationships in structure and tone, but without the explicit clarity of a wage relationship”: a review of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s The Outsourced Self.

Intimate Life in Market Times

by Arlie Russell Hochschild

Metropolitan Books, 2012, 320 pp.

A professional engineer who applies project management strategies to her search for love; an event planner who designs weddings that pay tribute to the singular story of a couple’s romance, a story she will also write for them; a businessman whose firm suggests his wife and children complete a performance review of him as a parent to determine how he can be a better father—and therefore happier, and therefore more productive. These are the subjects of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s brilliant but flawed The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times, a study of the commodification of family, friendship, and love that falls somewhere between scholarly analysis and pop sociology. If you’ve ever wondered what kind of party someone who specializes in “message platform and rebranding” would throw, read on.

Hochschild first coined the term emotional labor to describe the exchange of a socially desirable performance (“Just smile, honey”) for a paycheck. Her landmark 1988 work, The Second Shift, examined the stalled revolution that made employment outside of the home mainstream for American women while leaving them with the lion’s share of housework. A spiritual sequel to The Second Shift, The Outsourced Self is about the psychological and financial contortions that people go through to make the free market work in practice as well as in theory. Fortunately, it’s not the brooding misadventure in psychoanalysis that the title may suggest.

Hochschild is primarily concerned with the changing landscape and terms of service work—who does it, for whom, for how much, and why. Here, she takes the same documentary approach to market relations (what she calls “intimate life”) as she did to the study of the feminization of the labor force, using as a starting point not data but experience; the deceptively individual arrangements of everyday existence that, when assembled holistically, reveal the systemic contradictions at the heart of capitalism.

Once again, she’s done her homework. The Outsourced Self brings together hundreds of recent interviews conducted with wage earners, consultants, patients, and patrons engaged in all facets of the rapidly evolving and extraordinarily specific service industry. Familiar fields such as counseling, domestic work, entertainment, surrogacy, and end-of-life care are represented; as is a new wave of personal service providers dedicated to giving clients entanglement-free support in the special tasks that occupy our modern elites: determining what they want and reframing it into something achievable, identifying the most auspicious name in the family tree to hand down to future generations of visionary executives and entrepreneurs.

One of the most important feelings the market can sell us is the feeling of being authentically out of the market.

Weaving these accounts together with her own struggle to care for her aging Aunt Elizabeth, Hochschild laments that the intimate needs formerly provided for by the gift economy of the literal and proverbial village are today more often being bought and sold. Social relationships mirror wage relationships in structure and tone (that is, they are unequal), but without the explicit clarity of a wage relationship. One of the most important feelings the market can sell us, she observes keenly, is the feeling of being authentically out of the market. Never before has “a language developed that so seamlessly melded village and market—as in ‘Rent-a-Mom,’ ‘Rent-a-Dad,’ ‘Rent-a-Grandma,’ ‘Rent-a-Friend’—insinuating itself, half joking, half serious, into our culture.” The timeline for this melding is imprecise, but it falls suspiciously along the lines of Hochschild’s lifespan. Here’s her version of the story: “In 1910, a quarter of Americans lived in metropolitan areas, and by 2000, 80 percent did. Now more urban, Americans continued to express some village ethic of ‘just do’ with neighbors, friends, and co-workers. But for an increasing number, family became their village.” A few broad transformations—the rise of the working woman, the increase in divorce, and the growing insecurity and stress of the workplace “greatly undermined the family’s ability to take care of itself. The homemakers of yesteryear became the working women today…so who now would care for the children, the sick, the elderly?”

A good question—but hardly a new one, and Hochschild’s recurring depictions of her childhood home in a Northeastern farming town are not any kind of answer, only a nostalgic monument to an idealized past (the “pre-market way of life”) in which, she imagines, a collectivist attitude inspired neighbors to fill gaps in care by “just doing” for each other. Until she was ninety-four, Elizabeth’s needs were met, Hochschild says, by dinner invitations from the family up the hill and kind relatives who offered to take out her recycling and wash her hair. It’s clear she sees the agrarian society of the old country cottage as the vastly preferable alternative to the “encroachment” of market society that has made Americans myopically focused on results over process and dependent on transactions, rather than favors, to obtain them. But when Elizabeth develops a hernia that requires constant care, Hochschild recognizes that she faces a “care crisis” of her own: “I couldn’t quit my family and job in California to care for her in Maine. I couldn’t ‘just do.’”

A good question—but hardly a new one, and Hochschild’s recurring depictions of her childhood home in a Northeastern farming town are not any kind of answer, only a nostalgic monument to an idealized past (the “pre-market way of life”) in which, she imagines, a collectivist attitude inspired neighbors to fill gaps in care by “just doing” for each other. Until she was ninety-four, Elizabeth’s needs were met, Hochschild says, by dinner invitations from the family up the hill and kind relatives who offered to take out her recycling and wash her hair. It’s clear she sees the agrarian society of the old country cottage as the vastly preferable alternative to the “encroachment” of market society that has made Americans myopically focused on results over process and dependent on transactions, rather than favors, to obtain them. But when Elizabeth develops a hernia that requires constant care, Hochschild recognizes that she faces a “care crisis” of her own: “I couldn’t quit my family and job in California to care for her in Maine. I couldn’t ‘just do.’”

And who can? The ongoing forty-year policy project to dismantle and privatize the public sector in the United States has lead to a corresponding profound shift in American workplace culture and power relations. While advocating cuts to government services, CEOs and Chief Happiness Officers expect private workers to be “authentically connected” to their organizational mission 24/7. Are you really an accomplished leader with a future-oriented vision? Merely showing up at the office will get you nowhere; it’s your perpetual dedication to the bottom line, your hysterical enthusiasm, your investment in your identity as a worker, even at home, that counts. “Do Happy People Work Harder?” asks a 2011 essay written by Harvard Business School professor Theresa Amabile and published in the New York Times. It concludes that they do. A 2012 article in Inc.magazine gives small business owners a three-point plan on how to “Make Your Employees Motivated Missionaries.”

For time-starved employees expected to be not just physically but mentally on call around the clock, acts of kindness, sensitivity, communication, and patience once considered leisure—in fact, the very substance of life—can be as inconvenient as doing a load of laundry. Compelled by long work hours and a lack of bargaining power into complying with these demands on their time, the upper- and middle-class Americans who can afford it are increasingly willing to pay others to navigate their emotional lives for them. This is the “outsourcing” of the self referred to in the title (used here in the strictest sense to refer to a practice that is contracted outside of a company, rather than as a synonym for “offshoring”). The result is a society sorted not only by class, gender, and race but also by “emotional type,” with “order-barking, fast-paced entrepreneurs at the top, and emotionally attuned, human-paced mediators at the bottom.”

One upper-middle-class mother working long hours while breast-feeding a newborn son explains her decision to buy take-out and hire a nanny this way: “I don’t invest my identity in the stuff I hand off. I’m not a fantastic cook, so it’s no problem to order in or eat out….My self-esteem rests on excelling at that one thing—being an ace on the U.S. tax code. I don’t value myself for much else.”

She thought of herself as a devoted mother; in the greater scheme of things, that came first. But—crediting the productivity gurus whose best-selling books she’d devoured in business school—she wanted to focus on what she was best at, and she wasn’t sure that was motherhood…“What am I good at? I ask myself. Tax strategy. So I want to outsource everything except what I’m best at. I’m always asking myself: What can I outsource? Hopefully not me!”

Hochschild is right to point out that capitalism’s unrelenting push for profit has led to a colonization of the psyche of modern workers, who are, in the case of the upper and middle classes, encouraged to apply the narrow-minded logic of business to their own lives and, in the case of many care workers, to live among their employers. The argument that we expect different personality types from different classes is particularly smart. But again, the situation is not nearly as novel as she seems to think it is, and her conclusion that the service market “in all its expertise” is sapping the national self-confidence in “our own capacities, and those of friends and family…[because] the professional potty trainer does the job better than the bumbling parent or helpful neighbor” is unnecessarily diagnostic.

It’s not a lack of mettle from which her interview subjects suffer, but the entirely justified financial and psychological threat of unemployment and loss of class status. Even after cutting her hours back to thirty a week, a part-time job by today’s standards, the mother in question created a thirty-page PowerPoint presentation articulating her family’s values. What separates the ideology of goal-setting productivity from a cult and makes it mainstream is that it is so practical, even necessary, under free-market capitalism. There’s a reason members of the professional class can often be heard proclaiming that they work twelve-hour days because-they-love-social-media-marketing-so-much-they-just-can’t-stop-doing-it. Cultivating this identity is a requisite for keeping their job. They’re expected to live in an impossible state of continuous happiness, confidence, and passion or risk being replaced by someone who does a better impression of being a happy worker. Should we be surprised that they are willing to pay for support in this in inhuman endeavor?

Historically, the necessity of bringing up future workers has been begrudgingly conceded by capitalists to families. It’s interesting to note that the progressive state-run childcare policies of contemporary France, which serve as a touchstone for many of today’s feminists, were originally put in place to combat France’s falling birth rate. In contrast, the birth rate in America hit an all-time high in 2007. (It has since been falling at a rate faster than France’s.)

Characteristically, neoliberalism has had a seemingly “democratizing” influence: the services of governesses, nannies, and chauffeurs are accessible to a greater number of those outside of the old aristocracy. In fact, subtler economic coercions simultaneously limit or eviscerate the options of those who can’t pay while ramping up competition (and anxiety) among those who can. Today the spheres of “work” and “home” once separated by early industrial capitalism are being reintegrated through Peter Drucker–style managerial tactics that claim every second of a worker’s existence. For upper- and middle-class workers, this takes the form of bringing the principles of productivity into the home. For service workers, it means living in your employer’s home. It’s a new kind of enclosure, but instead of public land that’s being staked out by capitalists, it’s parts of the self.

Women also know especially well that within the service sector, some arrangements are more feudal than others. The closer to the home one works, the less bargaining power one has. Household managers, for instance, are expected not only to dust the Lichtenstein and drive the kids to the hockey rink, but also to live where they labor, to pledge allegiance to the family for which they work without being ofit. Wealthy couples frequently praise their nanny to Hochschild for acting with what they perceive as “sincere” feeling, while nannies seen as harboring material motives are distrusted and usually fired. Being part of the family means never asking for a vacation or a raise.

Two married software designers assert that they’re good employers because their nanny, Maricel, is “undocumented and poor. We pay her well and…she sends the money back to her family in the Philippines. Here she’s like part of our family. She’s helping us, but given their poverty over there, I like to think we’re helping her.” If you’re truly passionate about your work, the theory goes, you’d do it without being paid for it—and so wages, in the circular logic of the unselfconsciously privileged, become regarded as a glorified handout.

The same couple attributes Maricel’s loving treatment of their infant daughter to her “authentic,” family-oriented Filipina upbringing. Caring is just “in her bones,” they say. In fact, as Maricel tells Hochschild, the loneliness of their large, cold house led her to cultivate a close relationship with the baby, and it was Oprah who showed her how: watching the show she learned that “it’s good for families to say ‘I love you.’ To hug and kiss…In the Philippines it’s rare for a parent to say [I love you] to a child, especially among the poor, like we were.”

It doesn’t matter. When a nanny bakes and sells brownies for a child’s school bake sale, she’s not being paid for her services as a cook, but as a proxy parent. The same goes for the hugs and kisses. The software designers are trying to buy something intangible for their daughter—a relationship in which family values can be picked up like a second language, imported from abroad. And it’s not entirely an illusion. Maricel does seem to love Clare. But who takes care of Maricel’s daughter, still living in the Philippines? That detail is left out of the software designers’ story, because Maricel’s private life belongs to her employers, and rather than resent that fact, she’s supposed to enjoy it. (As one parent with an ailing mother told Hochschild, “it’s unprofessional to be upset.”)

The conflicting demands placed on care workers in the American economy are twofold. They are simultaneously deemed as impoverished beneficiaries of their employers’ graciousness and as free agents in the open market. They must be, on the one hand, genuine, and on the other, constantly, obsessively positive. This latter demand is a fundamental contradiction underlying nearly every contractual relationship in The Outsourced Self. In the service industry, the bond between client and provider is neither entirely familial nor entirely professional. Instead, it exists in an ambiguous state of in-between, clouded by shame and embarrassment.

Like nannies doing parental work, online dating consultants are used to being their clients’ “dirty secret.” Discretion is essential, and success involves making a client feel accomplished as a self-made man or woman, even at the expense of the worker’s own visibility and autonomy. In contrast to domestic workers, consultants live outside of the home and are endowed with expert status. They are seen as purveyors of specific skills and information, not just compassion, and are compensated accordingly. Positioned as curators of experience, they offer motivation, advice, and an antidote to their clients’ exhaustion and self-doubt. Ultimately, however, both serve the same function: they save time, calm insecurities, and soothe the soul in the face of endless work.

The limit of Hochschild’s critique is her inclination to write about the present as if it were a fall from grace. Each section of the book begins with a loving description of the way things used to be done, back in the day. Her grandfather riding a penny-farthing bicycle twenty-nine miles to court her grandmother Edith “face to face”—five hours there and five back—is contrasted with the online shopping approach of Match.com (“the world’s biggest candy store”) and the anonymous relationship advice peddled over the phone by love coaches. Edith’s wedding, a simple affair in a small, wooden Universalist church, consisting of farm cider, sandwiches, ice cream, cake, and “an evening of dancing to the tune of hired fiddlers” is juxtaposed with a picture of a wedding organized by Laura Wilson, specialist in wedding planning, that included 150 guests and a rented mansion. This anecdotal approach is inevitably misleading, because the difference here is one of class, not era. Edith lived, after all, during the Gilded Age.

The conflicting demands placed on care workers in the American economy are twofold. They must be, on the one hand, genuine, and on the other, constantly, obsessively positive.

Hochschild admits that the wealthy have long relied on hired help to dress them, nurse their children, take care of their sick, and cook family meals. But, she writes, “it was only in the 1970s, when women left the home for paid work that elder care began to move into the hands of professionals.” She seems to believe that the penetration of markets into internal and community relationships is historically unique. It is not. The “homemakers of yesteryear” were as hard-pressed as working mothers today engaged in the second shift. “The Woman’s Labour,” by seventeenth-century British poet Mary Collier, who worked as a washerwoman, addresses her double work load: “our tender Babes into the Field we bear,/ . . . you [men] sup and go to Bed without delay,/and rest yourselves till the ensuing Day/While we, alas! but little Sleep can have . . .”

Despite her undeniable empathy for the people she interviews—she never shames anyone for hiring a nanny—Hochschild’s American reverence for honest toil done in the context of a local community prevents her from envisioning a practical way forward. Instead, she looks back on a time of gladiolas, corn, and wreaths sold in stands by the side of the road next to change jars, “affirming a basic tenet of small-town life—‘around here we trust each other.’” She recalls being forced as a child to dust the parlor while her brother stacked shingles on the barn, and complaining that it was silly work. But her grandmother, she says, knew better: “the point of pride was the labor itself. That was the lesson: the near-sacred value of working together to grow our own food and put it on the table . . . When money did change hands, it did so differently.”

The wistful portrayal of village versus market ethics in The Outsourced Self is reminiscent of Sheila Rowbotham’s comment on the nostalgia of men and women living during the transition from agrarian to industrial society in eighteenth-century England: they “looked back with nostalgia to the time when they all worked at home….As the factory workers settled in the towns the countryside remained a memory,” like a “haunting melody.” But of course, conditions under agrarian societies were always quite harsh: starvation was common, the death rate was high, and division between rich and poor was extreme. This is not a model we want to reclaim any time soon. Hochschild herself admits the family was never financially self-sufficient, and she ultimately hires a part-time home health aide to help care for her aunt Elizabeth.

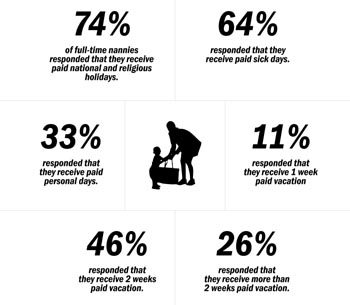

The possibilities of collectivization are appealing but today, for a variety of reasons (some of which make it into The Outsourced Self), it is impractical to look to local communities to provide them. What attracts Hochschild so deeply to the village is that, despite the boring chores, she felt a sense of belonging to something larger than herself. That sense of belonging could just as easily be provided by adequately funded state-run homes for the elderly and centralized childcare for infants and toddlers. The goal of the Left should not be to get the upper-middle class mother working long hours to quit her job and fire her nanny. It should be to socialize childcare so that the nanny has vacation days, sick leave, fair pay, and respect. This is not a pie-in-the-sky question: it’s a political one.

We must also distinguish among forms of emotional outsourcing that make us mere witnesses to our own lives from those that have the potential to free us. Thinking of service work as a form of out-sourcing prevents us from thinking critically about what forms of labor should be socialized. And it prevents us from embracing the ways in which technology might make our lives more bearable, since, no matter how much one says it, not all intimate, personal tasks are meaningful or enriching; some of them are just hard work.

The most surprising thing about market solutions is that sometimes they work. Therapists and counselors, for instance, are net positive developments for society. Even the “wantologist” offers sound advice to a depressed client who says she’d feel better if she had a bigger house, walks by the ocean, and relaxation. She suggests that the client fill a room in her house with a potted fig tree, ferns, and a water fountain. “The woman,” writes Hochschild, “found peace in her newly renovated medium-sized house and garden.”

Ironically, The Outsourced Self was lambasted in the Wall Street Journal for its emphasis on the “Americans on the upper slopes of the socioeconomic pyramid who seem to be the sole subjects of Hochschild’s research.” In fact, one of its many strengths is the way Hochschild simultaneously distinguishes and connects the different types of coercion experienced by American workers of all classes. Service workers and the people who hire them struggle with the extent to which transactional relationships can also be friendships, as the interviews and analysis in the book make clear. Still, it’s not the infiltration of the market into our relationships that is problematic, but the ever widening and broadening seizing of power from workers.

Megan Erickson is an editor of Jacobin.

Infographic by Imp Kerr