A Tangled Web: The Misguided Battle against Online Copyright Infringement

A Tangled Web: The Misguided Battle against Online Copyright Infringement

Liel Leibovitz: A Tangled Web

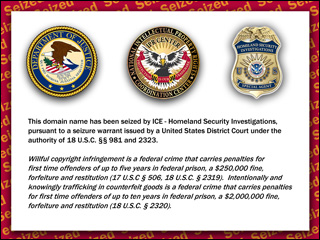

IF YOU happened to surf any one of eighty-two popular websites—from online purveyors of counterfeit luxury goods to torrent sites commonly used for unauthorized downloading of digital media like songs, movies, and television shows—on the Monday after Thanksgiving last year, you might have come across a strange and forbidding banner. Featuring three official government seals side by side—representing the Department of Justice, the National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center, and the Department of Homeland Security, each one emblazoned with its own menacing eagle—the banner announced that the website in question had had its domain name seized by the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigrations and Customs Enforcement Agency on account of “willful copyright infringement.”

IF YOU happened to surf any one of eighty-two popular websites—from online purveyors of counterfeit luxury goods to torrent sites commonly used for unauthorized downloading of digital media like songs, movies, and television shows—on the Monday after Thanksgiving last year, you might have come across a strange and forbidding banner. Featuring three official government seals side by side—representing the Department of Justice, the National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center, and the Department of Homeland Security, each one emblazoned with its own menacing eagle—the banner announced that the website in question had had its domain name seized by the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigrations and Customs Enforcement Agency on account of “willful copyright infringement.”

The virtual shutdowns were the pinnacle of Operation In Our Sites, a joint undertaking by the aforementioned agencies to combat the rampant abuse of intellectual property rights on the Internet. In a press conference announcing the operation, Attorney General Eric Holder justified the harsh steps by saying that “[intellectual property] crimes threaten economic opportunities and financial stability.” Unsurprisingly, several lobbying groups representing the music and the film industries enthusiastically agreed.

The reality, however, is far more complex. A 2004 paper by researchers at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, to name just one prominent bit of scholarship on the subject, found that even high levels of unauthorized music file-sharing have an effect on CD sales that is “statistically indistinguishable from zero.” Consumers, in other words, are perfectly willing to pay for music, but think nothing of illegally downloading songs or albums that pique their curiosity, but which they wouldn’t have otherwise bought.

Armed with such insight, the record industry could have been expected to invest dramatic resources in crafting digital delivery platforms, making the legitimate purchase of music online as convenient and pleasurable as possible. Instead, the industry spent years and millions of dollars combating the proliferation of file-sharing services with little or no success, lobbying for the cessation of unauthorized distribution of music while providing no legal alternative in its stead. Into the void stepped a computer company, Apple, proving just how profitable paid digital downloads of creative content could be. The company’s digital music delivery platform, iTunes, was set up as a convenient and intuitive electronic marketplace; it sold one million songs in its first five days. Another Internet company, Netflix, is currently pulling a similar play with Hollywood.

The reason for this shift has little to do with economics and much to do with epistemology: while the entertainment industries still see themselves as purveyors of tangible objects—CDs, DVDs, and so on—consumers are becoming rapidly accustomed to digesting their content digitally. Rather than coming to terms with this fundamental change, the corporate samurai who represent these industries are waving their swords, demanding that the laws serve not the needs of the consumer, or the logic of evolving technology, but the interests of their masters.

Unfortunately, legislators are listening. While the November shutdowns were limited to a one-time, concentrated effort, the philosophy that guided them might soon become law, courtesy of the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeit Act of 2010 (COICA), a bill that sailed through the Senate’s Judiciary Committee last October and that currently awaits a Senate vote it will likely pass. Introduced in September of 2010 by Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), the bill would “amend the federal criminal code to authorize the Attorney General to commence an action for injunctive relief against a domain name used by an Internet site that is ‘dedicated to infringing activities,’ even where such a domain name is not located in the United States.” The offending website’s domain name would then be suspended or locked, meaning that Internet users attempting to view the site would see a blank screen or an error message; temporarily or permanently, the site would cease to exist.

To understand the full implications of this measure, it is instructive to compare it to the current key legislation regulating copyright, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998. According to the DMCA, Internet service providers are not liable for any acts of copyright infringement perpetrated by their users, on the condition that they “adopt and reasonably implement” a policy of punishing repeat offenders. This leaves the task of identifying and addressing copyright infringement to the copyright holders themselves. Were a singer, say, to learn that someone had posted her work, without permission, on a certain website, she or her representatives could send the offending party a written notice and demand that the infringing content be removed. In legal terms, this sort of action is known as in personam, namely an act directed against an individual, and the DMCA assumed that the heavy penalties for infringement would be sufficient to deter most reasonable people from violating intellectual property rights.

Twelve years later, however, it is safe to say that the DMCA has failed to achieve any of its chief goals. According to surveys conducted over the last decade by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, the number of Internet users who say they don’t care about copyright is constantly increasing and currently hovers at around 70 percent. That number, unsurprisingly, is much higher among teenagers, for whom obtaining and sharing infringing content has become commonplace. And while several popular file-sharing websites, such as LimeWire, have been shut down, new technologies have risen with a vengeance. According to some estimates, the popular file-sharing protocol BitTorrent currently accounts for up to 55 percent of all traffic on the World Wide Web. The parties most hurt by these trends, the music and film industries, have demanded action. Enter COICA.

The new bill’s first major change is to replace the in personam with in rem action, or action directed against a specific property. Whereas the DMCA targets users, COICA will target websites. The former enables copyright holders to ask for the removal of a specific piece of infringing content, such as a video or an mp3 file; the latter will allow copyright holders to ask the government to shut down an entire website.

Supporters of COICA—most notably the Recording Industry Association of America and the Motion Picture Association of America—claim that the bill finally provides law enforcement agencies with the powerful weapon they need to fight lawlessness online. But COICA is likely to present more problems than it solves. Take, for example, the recent case of Viacom v. YouTube. Enraged by seeing episodes of the Daily Show, the Colbert Report, South Park, and its other popular shows posted to YouTube without permission, the media conglomerate took the video platform, now owned by Google, to court. Basing its decision on the DMCA, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the defendants, arguing that YouTube took reasonable measures to remove infringing content and was therefore not liable for its users’ actions. Should COICA pass, a similar lawsuit would have only to prove that YouTube, or any other website, is “dedicated to infringing activities,” an extremely vague designation on which the bill does not elaborate, to succeed in shutting down the site.

But the main reason why COICA is an ill-conceived piece of legislation has to do with logistics. The bill’s main measure of enforcement is to tamper with the Domain Name System, the protocol that translates URLs like www.dissentmagazine.org into the Internet Protocol addresses that computers read. When the IP address cannot be read, the corresponding website melts into air.

This potential assault on the network’s very architecture has drawn heavy criticism from technology experts who argue that the benefits of more effective measures to enforce copyright laws pale in comparison to the harm done when technology’s very infrastructure is compromised. Tim Berners-Lee, for example, the creator of the World Wide Web, released a statement last year denouncing COICA as a serious blow to progress. “In the spirit going back to Magna Carta,” he wrote,

we require a principle that: No person or organization shall be deprived of their ability to connect to others at will without due process of law, with the presumption of innocence until found guilty. Neither governments nor corporations should be allowed to use disconnection from the Internet as a way of arbitrarily furthering their own aims.

Most likely, Berners-Lee and the bill’s other critics have little to worry about. Even if COICA becomes law, it will most likely join a long list of acts that were designed to impede the sharing of copyrighted content but ended up prompting the ascent of new, more powerful media. In 1992, for example, President George H.W. Bush signed the Audio Home Recording Act into law, requiring every digital audio recording device sold in the United States to include technological measures designed to limit the number of copies the device could make. The law followed the introduction of new formats like Digital Audio Tape (DAT) and MiniDisc, which enabled consumers to make as many high-quality copies of their music as they pleased. The record industry rejoiced when the law passed, thinking it was safe from the menace of teenaged boys making crisp reproductions of the latest pop hits for their friends. But as the act focused on crushing DAT, a new format was emerging, designed to eliminate the necessity of physical data storage altogether; pretty soon, teenaged boys who wanted to swap music could simply send around an mp3 file, a technology much harder to police. The same is likely to happen should COICA pass; if DNS protocol is compromised, the hackers and activists who oppose the law are likely to create a new network, one even more porous and impossible to regulate than the one we have now.

What, then, are the titans of the media industry to do? There might not be one simple answer, but a stellar first step would be to rid themselves of a worldview that sees teenagers engaged in illegal downloading of content as terrorists, a term that the MPAA’S former president, the late Jack Valenti, used frequently and unreservedly. Nor, technically speaking, are they thieves—most Americans, in word and deed alike, see a distinct difference between shoplifting a physical copy of a CD, an object that is finite and irreplaceable, and illegally downloading the very same album and obtaining a file that can be reproduced and redistributed ad infinitum. This is more than a semantic difference, and the sooner media executives realize it, the sooner they can begin to view the problem as a crisis not of morality but of business models.

Once this ideological conversion is complete, the same executives may take heart in witnessing the myriad ways in which the new technology has facilitated the blooming of their business. They may draw inspiration from Kanye West, say, who for weeks prior to the release of his recent album last year leaked tracks, outtakes, and demos on blogs and social networks. His fans, thrilled with such unmitigated access to a process—the release of an album—that is usually tightly controlled, helped make the album a smash hit: both the CD and the digital version of the album debuted at the very top of Billboard’s 200 chart, selling nearly half a million copies in the first week alone. Even more radical was the British band Radiohead. In 2007, it ended its contract with its long-time label, EMI, and self-released an album entitled In Rainbows; rather than confine itself to the standard practices of sales and marketing, Radiohead offered In Rainbows as a digital download, allowing people to pay as much as they wanted for the album. While most people paid nothing at all, traditional advanced pre-sales alone were more profitable than the entire revenue of the band’s previous album. A deluxe CD set—which included additional material, like a handsome booklet—surpassed the 100,000 sales mark, an astounding success considering that its price, $80, was far steeper than that of an ordinary CD. Radiohead also invited fans to sketch storyboards for a music video based on one of the songs from the album, teaming up with a popular animation website and awarding the winner with a $10,000 production budget.

Both Kanye West and Radiohead chose to allow their fans greater access, inviting them to become part of the creative process; both understood that such immediate interaction was just the sort of stuff the Internet richly rewarded; and both profited handsomely in the process. And while Kanye and Radiohead had achieved their fames and fortunes prior to experimenting with new ways to distribute their music, there are many other examples to support the same notion, from artists who give away their albums for free and make their living from live concerts to companies like Pandora Radio that have found ways to make digital music more accessible and interactive.

A similar turn of thought is required of lawmakers. Rather than add layer upon layer to a policy infrastructure predicated on the premise that the goods in need of protection are tangible and scarce, they would do well to realize that digital files, immaterial and reproducible, require a logic all their own. Such revised legislation could, for example, distinguish between different types of copyright infringements, choosing, perhaps, to protect DJs remixing copyrighted songs or weaving them into inventive musical mashups and prosecute pirates who hawk unlicensed content online for profit. It could also follow the Creative Commons model. Founded in 2001, this nonprofit organization has released an assortment of copyright licenses that allow content creators to determine which rights they’d like to reserve. An artist recording a song, say, could choose to share it in return for nothing more than attribution, or to allow others to make use of the work for non-commercial purposes alone. For copyright law to be relevant, it must follow suit and recognize that the nature of cultural exchange on the Internet is porous and dynamic. Only if it addresses each of the various categories of online interaction—from amateurs clogging up YouTube with poorly produced tributes to their favorite action films to professionals who expect to be remunerated for their talent—can the law begin to meet the demands of the current cultural and technological landscape. Also, as Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig—co-founder of Creative Commons—noted in a recent speech, lawmakers must strive to make copyright law as simple to understand as possible. Unlike a few decades ago, when copyright law was the purview of a few professionals in the creative industries, Internet users are confronted with questions of copyright several times a day. Whether we surf the web for the latest pop hit, try to copy a legally purchased episode of our favorite television show from our computer to our portable device, or create a character in an online computer game, nearly everything we do online places us in the shadow of copyright law. To be relevant, any future piece of copyright legislation should be clear enough for a fifteen-year-old to understand.

Rather than come to terms with new technologies and new consumer demands, the captains of our creative industries, as well as our legislators, continue to have punishment on their minds. To that end, they will soon, most likely, pass COICA, once again pledging their allegiances to antiquated practices and obsolete technologies. If we truly wish to protect intellectual property, serve the public interest, and reinvent our struggling creative industries, we need not new locks but new keys.

Liel Leibovitz‘s most recent book is The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election, co-authored with Todd Gitlin. He is an assistant professor of communications at NYU’s Steinhardt school of culture, education, and human development.