Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize

Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize

Wasserstrom: Liu’s Nobel Prize

THIS YEAR’S Nobel Peace Prize generated an unusual amount of attention, due largely to the bravery and eloquence of the writings of the winner, the imprisoned gadfly intellectual Liu Xiaobo, but also to the mixture of expected and unexpected steps that the Chinese government took in responding to the situation. There was nothing surprising about Beijing being displeased by the award (many governments have been angered by past decisions of the Norwegian prize committee), nor was it unusual that the Chinese authorities blocked Liu from traveling to Oslo (other past winners have been in jail or denied exit visas). What was out of the ordinary was how far the government went to make sure that no one close to Liu would be able to accept it on his behalf (even Moscow had allowed Laureate Andrei Sakharov’s wife Elena Bonner to serve as his surrogate at the 1975 ceremony).

THIS YEAR’S Nobel Peace Prize generated an unusual amount of attention, due largely to the bravery and eloquence of the writings of the winner, the imprisoned gadfly intellectual Liu Xiaobo, but also to the mixture of expected and unexpected steps that the Chinese government took in responding to the situation. There was nothing surprising about Beijing being displeased by the award (many governments have been angered by past decisions of the Norwegian prize committee), nor was it unusual that the Chinese authorities blocked Liu from traveling to Oslo (other past winners have been in jail or denied exit visas). What was out of the ordinary was how far the government went to make sure that no one close to Liu would be able to accept it on his behalf (even Moscow had allowed Laureate Andrei Sakharov’s wife Elena Bonner to serve as his surrogate at the 1975 ceremony).

Also breaking from standard practice was the curious, last-minute effort to gin up an alternative “Confucius Prize” to celebrate someone China’s leaders viewed as more worthy than Liu–even if the prize was not as directly linked to Beijing as early reports in the international press suggested. Much about the prize remains murky, but the head of the prize committee apparently told AP that, while his group was not an official organization, it “worked closely with the Ministry of Culture.” (The idea for the prize was floated in mid-November in the Global Times, an officially endorsed organ tied to People’s Daily.) The inaugural ceremony for the award featured an angelic figure on stage with cash to give to the winner—who did not attend, and was reported to be unaware that he had even won.

In the case of the two unexpected reactions, as others have noted, there is only one clear historical precedent: the response of the Nazi government to the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Carl von Ossietzky, a crusading writer. Then, too, neither the laureate nor a family member was allowed to collect the prize (at a ceremony held in 1936); then, too, an authoritarian government created an award of its own, the “German National Prize for Science and Art,” to compete with the Norwegian one.

The way that all of this unfolded and the degree to which Beijing’s public relations efforts have backfired were detailed well by various writers, especially China-based journalists, during the weeks leading up to last Friday’s ceremony. And there were good pieces published on the ceremony itself, from a powerful post by the New Yorker’s Evan Osnos to a report from Oslo by the Guardian’s Peter Walker, which showed the value of the live-blog form, especially since the report was laced with occasional real-time updates from the paper’s Beijing bureau chief, Tania Branigan, reporting from China. My purpose here is to provide some wrap-up thoughts on the very significant way that historical analogies, including the German one alluded to above, came into play during coverage of the story, and to mention some aspects of Nobel Peace Prize history that tended to be overlooked, yet are worth keeping in mind as we reflect on how Liu and the 2010 award may eventually come to be seen.

THE NAZI analogy was a continual point of reference in foreign coverage of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, though never, for obvious reasons, a part of the Chinese official discourse on Liu Xiaobo. There is nothing new about efforts to draw parallels between China today and Germany in the 1930s. What was novel was the way that even people who have resisted the pull of this analogy in the past, stressing the differences between the two cases (and there are many very fundamental contrasts worth emphasizing), were struck by how illuminating it was for this particular set of official actions. Osnos makes this point eloquently in the post mentioned above. I have been critical of the comparison in the past (for example, I remain convinced that the parallels drawn between the 2008 Beijing Games and the 1936 Berlin Olympics were overstated) and expect to be critical of it again in the future. Still, for me, too, there was no denying the echoes of the mid-1930s in this particular instance.

Here is how Osnos sums up the current situation: “Chinese leaders know that they are harming their reputation around the world [in responding to the Nobel Peace Prize as they have], but they are calculating that the damage is temporary, and that they will ride it out. Perhaps, but the harm is substantial this time. China is not Hitler’s Germany, and now the comparison will endure in history.” He’s right, I think, both in stressing the limits of the parallels to be drawn, and in implying that the 1935 and 2010 peace prizes are likely to be grouped together routinely as a stand-alone pair in the future, in a way that the 1936 and 2008 Olympics, for all the efforts that Mia Farrow and others made at the time to brand the latter the “Genocide Games,” will not.

Even in this instance, it is worth keeping in mind that some Chinese government actions paralleled, even in their absurdity, those of authoritarian regimes of the past far less nakedly brutal than Nazi Germany’s—such as Poland’s, circa 1983. When Lech Wałęsa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize that year for his leading role in Solidarity, Warsaw did not create a competing award from scratch to honor a distinctively Polish approach to ethical behavior. It did do something, however, that seems in retrospect nearly as surreal. Along with denouncing the prize as honoring a figure intent on fostering instability rather than promoting peace (as the Chinese government did to Liu Xiaobo), the Polish government also, according to Irwin Abram’s The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History, banned “the music of Norway” on state radio. (It also banned, for a time, all American music. At the risk of seeming unduly nationalistic, I imagine that this was seen by listeners, at least youthful ones, as the more distressing limitation of musical offerings.)

The Polish case is worth remembering now for a more important reason: Liu Xiaobo has said that he wants his award to be seen as honoring the victims of the June 4 Massacre of 1989, and one thing that led the Chinese government to carry out those killings was a fear that, as workers joined students and intellectuals on the streets, something comparable to Solidarity would emerge in China. And June 4, 1989 was not just the day that workers and students were slain in Beijing, but also the day that Solidarity won its first electoral victory in Poland.

ONE THEME in Chinese media denunciations of the Nobel Peace Prize committee was its alleged bias toward the United States—something that also colored Polish and other criticisms of some past award decisions. Without giving this notion more credence than it deserves, it is certainly true that some prizes awarded to Americans have been baffling, including last year’s elevation of Barack Obama to laureate status (in spite of how little he had done) and the committee’s selection of Henry Kissinger in 1973 (in spite of how much he had done; songwriter Tom Lehrer’s comment that it was the “moment that satire died” remains memorable).

There is another American Nobel Peace Prize winner, though, who is in some ways more pertinent to remember when thinking about Liu Xiaobo than either Obama or Kissinger: Martin Luther King, Jr. Chinese children, like American children today, are taught to view him as a heroic figure who fought for things that well-meaning people around the world value, and not just those of a particular race, creed, or religion.

What is sometimes forgotten about Martin Luther King, Jr. is that, when he won the prize, he had not yet achieved the venerated status within the United States that he now has. Last year, when Obama won the Nobel Peace Prize, Newsweek ran a fascinating blog post that reminded readers of just how surprising and controversial seven previous awardees had been, including Kissinger. King gets mentioned, but in the category of past winners who “seem beyond dispute.” This would have been news in the 1960s to the FBI, which we now know was determined to bring King down. And even though nearly all Americans, whether on the right or the left, now celebrate his accomplishments and express admiration for his tactics, this was not the case when the Nobel Committee honored King in 1964. He had harsh conservative critics who thought him a wild-eyed radical as well as militant critics who chided him for not being radical enough. Both before and soon after King received his award in Norway, the prominent National Review contributor Will Herberg denounced King’s “rabble-rousing demagoguery,” blamed him for outbreaks of interracial violence, and generally presented as un-American a man who is now seen as exemplifying the values that Americans hold dear.

Liu should keep King’s later apotheosis in mind. For in addition to being denounced by the government, Liu has been chided by a few dissidents-in-exile for being too moderate, thanks in part to his powerful “I Have No Enemies” comment, which was just quoted in Oslo. Looking back to King’s Nobel moment and his later lionization reminds us of something important: how dramatically the reputation of a person who insists he has “no enemies”—even when he is being vilified—can change over time.

A shorter version of this piece appeared on December 10, 2010, the day of the Oslo ceremony, at the Huffington Post.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom is chair of the history department at the University of California, Irvine and the author, most recently, of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2010). An essay on protest in China, which he co-wrote with Maura Elizabeth Cunningham, will appear in the next issue of Dissent.

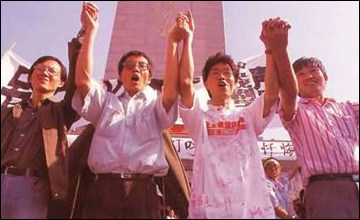

Image: Liu Xiaobo (second from left) with fellow hunger strikers in June 1989 (64memo.com)