Two Moralities? A Dissenting View

Two Moralities? A Dissenting View

Steve Max: Two Moralities? A Dissenting View

Even after the House Republicans? meaningless vote for a repeal of the health care program, the specter of that legislation is haunting the Social Security debate. A new theory has it that there has been a tidal change in the thinking of half the population, which now rejects government solutions to social problems and opposes taxing the fortunate to help the unfortunate. Believing that the recent electoral losses are due to what New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has described as a

The theory that the nation is now divided between what Krugman calls the ?two moralities? overlooks two points: 1) regardless of philosophy, stagnant income makes it difficult for many people to pay their tax bills and makes any increase a real hardship; and 2) in the case of health care, a prime example used by Krugman, many people, including large numbers of senior citizens, had specific reasons to oppose the program that have nothing to do with a ?new morality.?

Let us take a closer look at Krugman?s contention that the country is divided by two conflicting moral positions. He writes:

One side of American politics considers the modern welfare state?a private-enterprise economy, but one in which society?s winners are taxed to pay for a social safety net?morally superior to the capitalism red in tooth and claw we had before the New Deal. It?s only right, this side believes, for the affluent to help the less fortunate.

The other side believes that people have a right to keep what they earn, and that taxing them to support others, no matter how needy, amounts to theft. That?s what lies behind the modern right?s fondness for violent rhetoric: many activists on the right really do see taxes and regulation as tyrannical impositions on their liberty.

This seems to make sense, but does it? There are very few occasions when tax increases are actually earmarked for social safety net measures. Do we really know that people are more opposed to a tax increase, part of which might go to, say, Medicare, than they are to an increase in bridge tolls for their own private travel? Is this really about philosophy?or is it about the inability of most people to pay higher taxes?

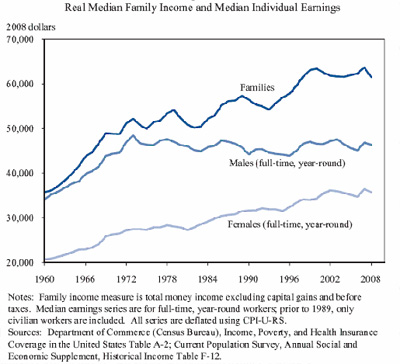

The key to understanding the prevailing atmosphere, I believe, lies in the stagnation of economic growth and income that is common to all mature market economies. The chart tells the story. Real (inflation-adjusted) median family income is lower now than in 2000, and earnings for male workers are below the 1972 level. To put it another way, average real hourly wages in the private sector rose all of fifty cents between 2001 and 2009. Generally speaking, wages rose faster for higher paid workers than lower.

When people?s income gets stuck for many years, they have no ability to pay for uplifting social improvements of any kind. To make matters worse, we Americans are schooled in the belief that in our otherwise perfect free market economic system, inadequate wages and unemployment are a result of our own personal failings. When faced with proposals for new social spending we feel we can?t afford, people wishing to appear neither inadequate nor mean-spirited will readily espouse anti-government ideologies, in much the same way that those who would conceal their sins avidly join crusades against the Devil. It is worth noting in this context that there has been a relentless drumbeat to reinforce the trickle-down lie that taxing the rich will mean job losses while shoveling money at them will bring full employment. Much of the frightened and dwindling middle class continues to hold onto this falsehood?never shown more false than by the economic realities of the past ten years.

As an illustration of the two moralities, Krugman turns to health care:

There?s no middle ground between these views. One side saw health reform, with its subsidized extension of coverage to the uninsured, as fulfilling a moral imperative: wealthy nations, it believed, have an obligation to provide all their citizens with essential care. The other side saw the same reform as a moral outrage, an assault on the right of Americans to spend their money as they choose.

This reflects a fundamental mistake increasingly common among progressives. No one, except advocates of a single payer system, ever proposed a health care bill providing all citizens with essential care! When we espouse timid half-measures, we shouldn?t be surprised that people reject them. Proponents of the health care reform legislation signed by the president were actually advocating a program essentially for lower-income workers that everyone else thinks they are going to pay for, but which is actually being financed by a half a trillion dollar cut in Medicare. The new program brings very little benefit to the 84 percent of the population that already has health insurance. It mostly provides partial subsidies for lower-paid individuals and small businesses. Perhaps Krugman is right that the same middle-class people who object to the current health care program would also oppose one that benefited them as well, but that should not be assumed.

Senior citizens occupy a rather unique position in this discussion. They do believe in a social obligation to provide health care, and yet many opposed the legislation. I recently attended a seminar with thirty organizers of senior citizens from all parts of the country. I asked them informally if the seniors with whom they worked were aware of the half a trillion dollar Medicare cut in the health care bill. The answer was virtually unanimous?seniors knew and were furious about it. It has been argued that the cut is justified because much of it is targeted at Medicare Advantage, a Republican-inspired program aimed at privatizing Medicare. On the policy level this may be right, but the political reality is something else. There are eleven million people in Advantage programs and another thirty-three million in conventional Medicare. Forty-four million is a rather large number of people to anger at one time. Even if only half of them believed that something was taken away from them in the health care legislation, that is certainly a big enough group to have an impact on the national discourse.

In the 2010 election, seniors voted in record numbers, making up 21 percent of the electorate according to a Project Vote survey. They voted 58 percent Republican, an increase of ten points over the 2006 election. Certainly, this angry senior vote was enough to cause the loss of many Democratic swing districts. That loss, in turn, adds to the general perception of growing support for the right-wing outlook, but it was actually caused by the administration?s foolishly shortsighted policy and the failure of progressive organizations to oppose Medicare cuts. Seen this way, much of the 2010 electoral loss can be accounted for by factors not related to the moral division that Krugman posits.

The danger now is that the ?two moralities? viewpoint will become the justification for unconscionable Social Security ?reforms,? such as lowering benefits, increasing the retirement age, or establishing private investment accounts. Krugman himself will no doubt oppose these measures. For others, however, his argument could lead to the belief that because half the nation thinks that individuals should pay their own way, we can?t raise taxes for Social Security?specifically, by eliminating the cap so that people would pay the Social Security tax on incomes above $106,800. (The median 2010 U.S. income was $42,326. Even though median household income is higher than this, removing the Social Security cap would only affect roughly the richest 5 to 7 percent of the population.) The result of ?saving? Social Security by cutting it, instead of raising revenue, may well make the program less appealing to both younger and older voters. If this happens, the political dominos set in motion by the health care bill will continue to fall?to the detriment of the Democrats, the elderly, the poor, and any hope of preserving one of the greatest social programs of all time.