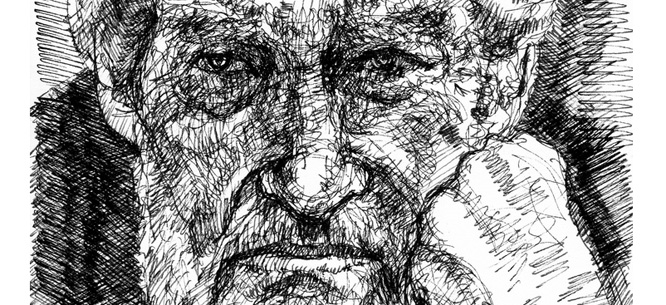

Poetry and Action: Octavio Paz at 100

Poetry and Action: Octavio Paz at 100

Octavio Paz spoke out against American imperialism in Latin America throughout his career, but his outspoken opposition to Stalinism and revolutionary violence got him smeared as a Reaganite. On the poet’s centenary, a look at his politics and his most comprehensive collection in English.

1.

When protest movements spread through cities around the world in 1968, Octavio Paz looked upon the “great youth rebellions . . . from afar,” he wrote, “with astonishment and with hope.” The poet was then Mexico’s ambassador to India. He escaped the summer heat of New Delhi into the foothills of the Himalayas, following developments on the radio. Soon, he learned that Mexico had joined the rebellions. Mexico would host the Olympics in October. As protests grew entrenched, and students threatened to disrupt the games, government repression intensified. On October 2, hundreds of student protesters were killed at Mexico’s City’s Tlatelolco Plaza. Hearing the grim news, Ambassador Paz’s response was a swift vote of no confidence, a letter of unambiguous dissent. It was, as he described the rebellions themselves, the merging of poetry and action, a merger he constantly craved.

Paz was poetry’s great universalist. Winner of the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature, he absorbed many of the great movements of the twentieth century: Marxism, surrealism, the European avant garde. Early in the Spanish Civil War, he tried his hand at social realism, and he admired North American poetry, especially Whitman, Pound, Eliot, and Williams. His ambassadorship to India in the 1960s introduced him to the pillars of Hindu and Buddhist thought.

In 2012, in anticipation of the fifteenth anniversary of his death, New Directions brought out The Poems of Octavio Paz. All but ignored since publication, The Poems deserve attention, because—in addition to being frequently masterful, and impressively translated into English—they represent hybridity, universality, and an aesthetic and political middle way. As we approach Paz’s 100th birthday later this month, it’s worth looking again at the life and work of a man unfairly maligned as an apologist for the right during the final decade of the Cold War.

2.

Born in 1914, Paz was raised in Mixcoac, today a part of Mexico City. He grew up in a house he described as disintegrating:

Our family had been impoverished by the revolution and the civil war. Our house, full of antique furniture, books, and other objects, was gradually crumbling to bits. As rooms collapsed we moved the furniture into another. I remember that for a long time I lived in a spacious room with part of one of the walls missing. Some magnificent screens protected me inadequately from the wind and rain.

At seventeen, he published his first poem, “Game.” Two years later came his first book, Luna Silvestre. Also at a young age, he witnessed the first incident in what became one of his lifelong obsessions: political repression. It was late in the Mexican revolution, when Paz and his mother were traveling to meet his father, a political journalist and lawyer for Emiliano Zapata. They were traveling by train, under armed protection, to visit the elder Paz, who was exiled in San Antonio, Texas, when suddenly Paz’s mother covered his eyes. This had the ironic effect of waking him, while failing to shield him from the grim sight outside the train. “I saw an elongated shadow hanging from a pole.” He was six.

At the invitation of Pablo Neruda, Paz traveled to Valencia, Spain in 1937 to join the Second International Congress of Anti-Fascist Writers. He spent a year there before going to Paris, where he advocated for the Spanish Republic. He met poets W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Antonio Machado, Tristan Tzara, and of course Neruda. The civil war steered his poetry into a short-lived social realist mode, perhaps his first attempt to join words and action.

“Elegy for a Friend Dead at the Front in Aragon” and “Ode to Spain” stand out as examples of this effort; the former addresses Paz’s “comrade” and finds brief moments of felicity in the psychology of grief and loss, asking, “What fields will grow that you won’t harvest? / What blood will run without your heirs? / What word will we say that doesn’t say / your name, your silence, / the quiet pain of not having you?” Paz also became known for “No Pasaran,” or “They Will Not Pass,” a call to arms in verse that caused a minor sensation.

Upon his return to Mexico City, he launched a magazine of new Mexican poetry named Taller (Workshop). Ambivalent about the European avant-garde, Paz’s opening manifesto cited copiously the Spanish perspectivist philosopher Jose Ortega Y Gasset, declaring that the purpose of the magazine was “to be not the place where a generation is erased but the place where the Mexican is being made and is rescued from injustice, from a lack of culture, from frivolity and death.”

During the Second World War, Mexico became a haven for displaced Europeans; amid the capital’s newfound cosmopolitanism, Paz met refugees like Victor Serge. He also edited a massive anthology that brought together Spanish-language writers in a controversial way: he allowed political opponents to sit alongside one another in its pages. What his most important translator, Eliot Weinberger, calls his “first substantial collection” of poems, On the Bank of the World, appeared in 1942; in one poem in the book, he wrote, “He wanted to sing, to sing / to forget / his true life of lies / and to remember / his lying life of truths.”

After the war Paz took a low-level post in the Mexican foreign service in Paris, where he met Andre Breton and Albert Camus; there he fell in love with the streets, and his encounter with surrealism deepened. Paz’s lifelong meditation on poetry and words doing something now led him to abandon realism in favor of more experimental verse. “I should say that I write as if in a silent dialogue with Breton,” Paz once admitted. In an introduction to his work, Michael Schmidt amplifies this sentiment: “Under Breton’s influence, Paz tried automatic writing and produced his great prose-poems. But it’s interesting that in his valedictory essay on Breton, Paz quotes none of his master’s poetry, only his critical statements.”

Being abroad also helped clarify his understanding of his native Mexico. “Solitude is the profoundest fact of the human condition,” he wrote in Labyrinth of Solitude, his book-length essay deciphering the Mexican character. By denying one part of their identity, that of the indigenous (which Paz inherited from his father), Mexicans had become stuck in a world of solitude, he wrote. Paz’s time outside the country allowed him a rare outsider’s perspective, something afforded to his father before him by his times in exile.

Paz loved writing and wandering in Paris, but politics again intruded and sent him into a second exile. In the summer of 1951, he attended a fifteenth anniversary commemoration of the start of the Spanish Civil War; the director general of UNESCO, also a poet, thought this improper and suggested Paz be transferred to South Asia. Paz was apoplectic. “Knowing that I was being sent to India consoled me a little,” he wrote, “rituals, temples, cities whose names evoked strange tales, motley and multicolored crowds, women with feline grace. . . .” He traveled by boat from Europe to Cairo, to Aden, and onto Bombay. Aboard the Polish ship Batory, he met Auden’s brother and the writer Santha Rama Rau, who wrote the film adaptation for A Passage to India. A little more than a week after arriving in Bombay, he took the train to Delhi; for Paz, those tracks that evoked images of post-partition sectarian riots also recalled his early exile to San Antonio. Paz’s stay in India was to be short-lived; having hardly arrived, he was transferred to Tokyo.

Paz continued writing throughout this period; he considered one long poem he produced during this time, “Sunstone,” published as a chapbook in 1957 (and later in Violent Season), to be the hinge from his earlier to later work. Along with The Labyrinth of Solitude, “Sunstone” also propelled Paz’s international reputation, notes his translator Weinberger. A poem of Mexico, Europe, and New York, of war and love, a meditation as if in one long exhalation across dozens of pages, it sports a trope Paz would keep polishing for the rest of his life: a return to origins through an un-self-conscious love amid history and ruin: “in the Plaza del Angel the women were sewing / and singing along with their children, / then; the sirens’ wail, and the screaming, houses brought to their knees in the dust, / towers cracked, facades spat out / and the hurricane drone of the engines: / the two took off their clothes and made love / to protect our share of all that’s eternal, / to defend our ration of paradise and time. . . .”

The 1960s marked the publication of the collections Salamander and East Slope, among others, and his marriage to Marie-Jose Tramini. He also studied Indian art and philosophy during that decade, organizing the first exhibition of Tantric art in the West. Paz continued to publish other works as well: he printed book-length studies of Claude Levi-Strauss and Marcel Duchamp. Some of that work took on a meditative tone, for example “Stillness,” published in East Slope:

Stillness

not on the branch

in the air

Not in the air

in the moment

hummingbird

3.

In 1968 Paz found himself in the Himalayan town of Kasauli, “an old summer retreat for the British,” as he followed the youth rebellions taking place around the globe. Initially he found the Paris rebellion “the most inspired,” as “the words and acts of those young people seemed to me the legacy of some of the great modern poets who were both rebels and prophets: Blake, Hugo, Whitman.” As protests intensified, he and Marie-Jose listened for updates on a short-wave radio. The protests joined his other obsessions: “Poetry, heir of the great spiritual traditions of the West, had become action.” Although Paz changed his mind about the rebellions’ significance several times, his mood was consistently electric.

“Perhaps Marx had not been wrong,” he thought, wandering the foothills, “the revolution would explode in an advanced country, with an established proletariat educated in democratic traditions. That revolution would spread throughout the developed world, and would mark the end of capitalism and of the totalitarian regimes that had usurped the name of socialism in Russia, China, Cuba and other places.” When, back in New Delhi, Paz heard that Mexico City, too, was embroiled in the rebellions, he felt their weight. The rebellions in Mexico, he felt, “lacked the poetic and orgiastic anarchism of the Parisian rebels,” but they did have one concrete demand shared by much of the country: democracy.

In late September, Paz wrote a memo attempting “to justify the positions of the students, insofar as they were concerned with democratic reform. Above all, I recommended that force not be used and that a political solution be found to the conflict.” He was told that his memo had been read with great interest and shown to the president. He slept well for ten or twelve days, “until,” he writes, “on the morning of October 3, I learned of the bloody repression of the previous day. I decided I could no longer represent a government that was operating in a manner so clearly opposite to my way of thinking.”

Paz spent the next few years teaching at Cambridge University, the University of Texas, and Harvard. He recorded the shock of his 1971 return to Mexico after ten years’ absence in a new book of poems called Vuelta. He also launched a magazine of the same name that would last the twenty-two years until his death, a magazine that Weinberger and others count among “the leading intellectual magazines in Latin America of their time, unmatched in [its] range of concerns and international contributors.”

In his remaining decades he published autobiographical poetry in A Draft of Shadows; The Monkey Grammarian, at once an essay, prose poem, and novel; a collection of translations from six languages; a book-length study of poet Xavier Villaurrutia; his Harvard lectures on romanticism and the avant garde, Children of the Mire; and four books of essays. During the 1980s, his work on Vuelta magazine—among interviews, lecture tours, and controversies over his punditry—would result in what Weinberger describes as “his anti-authoritarian European-style socialism . . . considered right-wing by the Latin American left.”

4.

Nearly thirty years after Paz’s resignation as ambassador, I called him up in Mexico City. I had spent two years in Costa Rica, writing, teaching, and learning Spanish, and I was heading home for Christmas. I crossed Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula by bus, and then flew to Mexico City, where I had a few days before returning to New York City.

I had found Paz for the first time in a used bookstore and cafe in Peekskill, forty-five miles up the Hudson from midtown Manhattan, just before embarking on those two years overseas. It was a small, yellowing collection among the unkempt shelves: Early Poems (1935 to 1955). My courses on Hispanic literature, as one textbook dubbed it then, rarely came past the Spanish Civil War. Paz was likely the first writer I picked up by chance, having heard nothing about him.

Late at night in the weeks before leaving the United States, I read of the ruins I would see, and of Paz’s walks through Paris and Mexico City. The poems taught me to listen differently, to listen to his listening; even in translation I could hear the listening present in Paz’s work, and the perpetual noon landscape, under a burning sun that was present time: “Time doesn’t blink, / time empties out its minutes, / a bird has stopped dead in the air. // . . . The air is transparent: / if the bird is invisible, / see the color of its song.” My response to the ruins we visited that winter, in El Salvador, at Tulum, Uxmal, and north of Mexico City at the Temple of the Sun and Moon, often came in Paz’s voice. At Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, I recalled Paz’s “In Uxmal”: “The light crashes, / the columns awake and, / without moving, dance. // . . . In the sun the wall breathes, throbs, undulates … And above so much life the snake / with a head between its jaws: / gods drink blood, they eat men.” At Teotihuacan, I flipped pages until I found Paz’s “Hymn Among the Ruins”: “To see, to touch each day’s lovely forms. / The buzzing of light, darts and wings. / The winestain on the tablecloth smells of blood. / Like coral branches in the water / I stretch my senses into the living hour. . . .”

I didn’t get him on the phone. I found several entries for Octavio, or O., Paz in the phone book at my hotel; I narrowed them down by looking for Marie-Jose’s name, which was listed with his. A woman who didn’t identify herself told me he would be back later. Was it really his number? I never called back.

Instead, I carried with me Paz’s hypno-realism, his vertiginously clear jumbling of the senses. The later Paz would develop what he called a politics and poetics of the now, the perpetual present; early Paz believed in history as an aberration. Jose Manuel Zamorano Meza traces to Heidegger “Paz’s romantic assessment of Western history as an error that should be corrected by returning to the origin.”

5.

The fall before I left for Latin America, I took a poetry workshop. Just before it ended, the professor, a Columbia poet, saw my desk piled with Paz’s books and commented dismissively on his politics, in an attempt, perhaps, to excise Paz from my pantheon. I’d felt perplexed by it; I’d already read essays from such collections as The Other Voice and had seen that Paz’s soaring love of freedom transcended nationalism and was clear in its denunciation of repression. What did my professor mean? Was he spreading hearsay?

Because Paz denounced Stalin’s atrocities, he distinguished himself (often explicitly) from Pablo Neruda, who in 1953 was famously awarded the Stalin Peace Prize, as Ilan Stavans notes in a new collection of Neruda’s odes (All the Odes). But Paz distinguished himself, too, from poets and intellectuals enlisted as cultural cold warriors, like Robert Lowell, Emir Rodriguez Monegal, and Stephen Spender. While Paz represented the kind of Latin American liberal the interventionist cold warriors liked to champion and fund—figures referred to collectively as NCL, or the non-communist left—Paz’s positions often started with assumptions surrounding the history of the damage, destruction, and dangers of American imperialism; his anti-communist views appear to have been un-coerced and predated the quiet funding channels that came to Latin America starting in the early 1950s, in the form of at least seven magazines: Examen, published in Mexico; Combate, published in Costa Rica; and Cuadernos, Cadernos Brasileiros, Temas, Aportes, and Mundo Nuevo, published in Paris.

Encounter, the flagship CIA magazine published in England from 1953 until 1991 and edited by Spender, also had an edition in Spanish. These magazines were funded by the CIA’s propaganda outfit, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, in some cases funneled through a Latin American think tank or a nonprofit like the Ford Foundation. They ran in tandem with campaigns that included CIA-embedded poetry tours (Lowell in South America) and the campaign (by CIA man John Hunt) to deny Neruda the Nobel Prize in the early 1960s. (He would win this prize in 1971.)

Peter Coleman writes that the Congress for Cultural Freedom–affiliated Cuadernos ought to have had “natural allies” in Paz, Carlos Fuentes, and others associated with Revista Mexicana de Literatura,“but they disliked Cuadernos so much that they refused to publish an advertisement for it.” American adventures, including the 1954 CIA overthrow of the democratically elected Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala and the Bay of Pigs invasion, somehow failed to endear Latin American leftists to the American proposition, whatever fond or fawning interest their magazine launches may have shown many of these writers.

Paz did appear in the CIA’s Mundo Nuevo. But this is likely because it was better-disguised propaganda than the quasi-McCarthyite Cuadernos. Mundo Nuevo also published leftists like Neruda and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who would have had nothing to do with a magazine known to be funded by the CIA. In Our Men in Paris? Russell Cobb writes that “[Carlos] Fuentes and Octavio Paz had little respect for the CCF (Congress for Cultural Freedom); the fact that Mundo Nuevo was able to attract both figures to contribute to the magazine is illustrative of its significant break with the organization’s anti-Communist politics.”

Why, when others were failing to take up the middle ground, was Paz able to position himself this way—namely, remaining critical of both American imperialism, on one hand, and the Soviet betrayal of socialist principles on the other, and noting, too, the betrayal’s taint on the Latin American left? It was in part because Mexico was a haven for refugees like the Russian writer Victor Serge, who “opened [Paz’s] eyes to the realities of life in the Soviet Union,” according to Joseph Roman.

Paz wrote:

When I consider Aragon, Eluard, Neruda and other famous Stalinist writers and poets, I feel the gooseflesh that I get from reading certain passages in the Inferno. No doubt they began in good faith. How could they have shut their eyes to the horrors of capitalism and the disasters of imperialism in Asia, Africa, and our part of America? They experienced a generous surge of indignation and solidarity with the victims. But insensibly, commitment by commitment, they saw themselves become tangled in a mesh of lies, falsehoods, deceits and perjuries until they lost their souls.

He is similarly unsparing in his indictment of other beloved figures of the left, such as fellow Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo:

Diego and Frida ought not to be subjects of beatification but objects of study—and of repentance . . . the weaknesses, taints, and defects that show up in the works of Diego and Frida are moral in origin. The two of them betrayed their great gifts, and this can be seen in their painting. An artist may commit political errors and even common crimes, but the truly great artists—Villon or Pound, Caravaggio or Goya—pay for their mistakes and thereby redeem their art and their honor.

Was he conciliatory? Certainly not. Was this the problem with Paz? Almost two decades later, I emailed my former professor to see which veritable crimes on Paz’s part so stuck in his craw, even with the Cold War long over. It turns out it was Paz’s critiques of Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, and his alleged apologia for the right. I asked Eliot Weinberger, too, what ignited the Latin American left’s disdain for Paz. Weinberger writes, “Because of his criticisms of the Sandinistas, [the Latin American left] thought he was supporting Reagan in the Contra war, and had a demonstration where his effigy was burned.”

So, what did Paz actually say? As he accepted the 1984 Prize of the Association of German Editors and Booksellers in Frankfurt, Paz defended an author he had published in Vuelta. Gabriel Zaid (who was also published in this magazine) had argued that it was time to submit “the Sandinista government to a popular vote in Nicaragua,” as Enrique Krauze recounts in Redeemers. The article was well received internationally, including in the New York Review of Books, “but [was] strongly attacked by many Mexican publications.”

On stage to receive the award, perhaps feeling partly responsible for the uproar, Paz defended his author (though not by name). First he traced “the history of the Somoza ‘hereditary dictatorship,’” which had “grown up in Washington.”

Paz continued:

Shortly after the [Sandinista] triumph, the case of Cuba was repeated: the revolution was confiscated by an elite of revolutionary leaders. . . . From the beginning the Sandinista leaders sought inspiration in Cuba. They have received military and technical aid from the Soviet Union and its allies. The actions of the Sandinista regime show its will to install a military-bureaucratic dictatorship in Nicaragua according to the model of Havana. They have thus denaturalized the original meaning of the revolutionary movement.

Did any of this substantiate the allegation that Paz served as apologist for the right? In addition to the line above about Washington supporting the reviled Somoza dictatorship, and his repeated acknowledgments of the left’s legitimate grievances against American imperialism, Paz added that “technical and military aid to the anti-Sandinista Contras was encountering growing criticism from the U.S. Senate and American opinion.” Presumably, if the rationale for the Sandinistas accepting Soviet funding via Cuba had been American funding of the Contras, that would soon go away. As indeed it did.

Paz had written that “the United States has been one of the principal obstacles we have encountered in our efforts to modernize ourselves.” That’s hardly Reaganite claptrap. Was Paz being read selectively by a left that, up against the wall of anti-communist incursions, required lockstep obedience rather than open discussion or frank criticism of its own side? A few years later, in “Poetry, Myth and Revolution,” he wrote, “The critics of revolution have been those nostalgic for the old order [conservatives], and liberals. . . . The liberal criticism has been more effective than the reactionary criticism.” Paz sees the real conversation in the time of the Berlin Wall’s crumbling as one between the liberal and the socialist strains of thought. Liberalism’s issue was that it left too many questions unanswered, and placed a distance between fraternity and liberty. Socialism created the temptation of a meta-history, false scientism, and, at its worst, collapsed the balance altogether, allowing the pretense of fraternity to erode liberty—and then dissipate into atrocity.

Scholar Maarten van Delden has recounted how at the time of the Frankfurt kerfuffle, Paz understood Nicaragua’s anti-Americanism, and merely asked why it should lead the Sandinistas to align with the Soviet Union. Paz cited Chateaubriand: “The Revolution would have carried me along . . . but I saw the first head paraded on the end of a pike, and I recoiled. I shall never look on murder as an argument in favor of liberty. I know of nothing more servile, more cowardly, more obtuse than a terrorist. Did I not find, later on, that entire race of Brutuses in the service of Caesar and his police?” Paz also wrote a “lengthy analysis of the Central American crisis,” Van Delden adds, “published in Vuelta in October 1987, [in which he] stated firmly that his defense of democracy should not be confused with ‘the defense of North American imperialism, nor with that of Latin America’s conservative military regimes.’”

Compare this with Borges’s “ringing endorsement of Gen. Pinochet’s activities in Chile,” as Clive James once described it at Slate. “There was a torture center within walking distance of [Borges’s] house [in Buenos Aires], and he had always been a great walker,” wrote James. “He could still hear, even if he couldn’t see. There was a lot of private talk that must have been hard to miss; a cocked ear would have heard the screams.” It would seem to make Borges a better target than Paz for Latin American apologist for the right, but he has never received the level of venom directed at Paz.

So was his Frankfurt speech taken out of context? Was it merely a betrayal of the shibboleth that the enemy (the USSR) of my enemy (the USA) is my friend? Krauze recounts Paz’s reaction to the row that followed the Frankfurt speech:

My first reaction was an incredulous laugh. How was it possible that a rather moderate speech unleashed such violence? Then a certain melancholy satisfaction. If they attack me it’s because [what I said] hurts them. But—I confess to you—it also hurt me. I felt (and I still feel it . . .) that I was the victim of an injustice and a misunderstanding. In the first place . . . it was an action conceived and directed by a group with the intention of intimidating all those who think as I do and dare say it.

What “violence” so hurt Paz, just five years before the Ayatollah’s fatwa on Salman Rushdie? Krauze describes it vividly: “A large crowd marched in front of the American embassy on Paseo de la Reforma (a short distance from Paz’s apartment) carrying effigies of President Ronald Reagan and Octavio Paz. Some of them chanted ‘Rapacious Reagan, your friend is Octavio Paz’ (‘Reagan rapaz, tu amigo es Octavio Paz!’). Someone lit a match and the effigy of Paz went up in flames.”

6.

Despite Paz’s failing health, the 1990s saw the publication of eight more books of his prose, including a massive study on the Mexican poet Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz; three more books of essays; a survey of contemporary international politics, titled One Earth, Four or Five Worlds; a survey of love and eroticism; an accounting of his politics from early Marxism onward; and a survey of Indian art and culture embedded with recollections of his time there. He also released another book of poems, A Tree Within; won the first Nobel Prize in Literature awarded after the fall of the Berlin Wall; and published a massive fifteen-volume edition of his complete works.

As the title of his first published poem suggests, Paz was a poet obsessed with process; and like Cortazar and Borges, he loved games. His poems about times of day, interstices between coming and going, petrification, and the annihilation of time often read like exercises, however advanced. Paz confessed to Chilean novelist (and outgoing ambassador to France) Jorge Edwards that having dismissed Neruda for his politics, he had reread his entire oeuvre in the decades after Neruda’s death and begrudgingly admitted that Neruda was that generation’s finest poet. Still, their poems reflect a drastically different worldview, aesthetic as well as political. A pair of socks in Neruda was, first, a pair of socks, suggesting the worlds, rooms, and lives of real people behind them. Objects in Paz’s work, on the other hand, read as transmutations, state changes—attempts to effect in words the canvasses of Joan Miró, the theories and games of John Cage. Paz is the Poet Laureate of synesthesia. Nothing—senses, self, time—is stable, as he conveys in “The Street”:

It’s a long and silent street.

I walk in the dark and trip and fall

and get up and step blindly

on the mute stones and dry leaves

and someone behind me is also walking:

if I stop, he stops;

if I run, he runs. I turn around: no one.

Everything is black, there is no exit,

and I turn and turn corners

that always lead to the street

where no one waits for me, no one follows,

where I follow a man who trips

and gets up and says when he sees me: no one.

Compare this with “Borges and I,” which appeared more than a decade later, and the famously cerebral Borges’s disquisition on the self almost reads as sentimental. (Paz didn’t write much fiction, but he did write a play, was a far better poet than Borges, and was Borges’s equal as an essayist, although he was less coy.)

Even when the lowercase, everyday self appears in Paz’s work, its bodily and even psychological craving is overwhelmed by the spiritual pursuit of redemption through literature. Craving nicotine, Paz writes in “The Poet’s Work,” “I turned toward a nearby cafe where I was sure to find a little warmth, some music and, above all, cigarettes. . . . I walked two more blocks, shivering, when suddenly I felt—no, I didn’t feel it: it suddenly went by: the Word. The unexpectedness of the encounter paralyzed me. . . .”

Paz’s shorter, process-laden poems—like architecture with its structure exposed—at times feel austere. His longer poems are more capacious and Whitmanesque, filling themselves with ordinary objects in a steady stream, buffeted along by the sorcery of chiasmus. His long autobiographical poem, A Draft of Shadows, bowls you over with a rhythmic onslaught of his ambling, riverine veering, until family and childhood details finally start to peek out from middle-length lines, like a startling—if startlingly casual—confession that the self may, in fact, have a history, despite its instability.

His rare poems addressing a “you” perhaps best of all unite word and deed, focusing his intricate and austere alchemy, and serving as a stand-in for the reader.

In one of these, he commands,

listen to me as one listens to the rain,

without listening, hear what I say

with eyes open inward, asleep

with all five senses awake,

it’s raining, light footsteps, a murmur of syllables,

air and water, words with no weight:

what we were and are,

the days and years, this moment…

Paz is most intelligible and affecting as a love poet, when the third person abstractions (“Time,” say) are softened by an I and you. Take “January 1,” one poem sorely missing from the otherwise judiciously curated new collection:

Time, with no help from us,

had placed

in exactly the same order as yesterday

houses in the empty street,

snow on the houses,

silence on the snow.You were beside me,

still asleep.

The day had invented you

but you hadn’t yet accepted

being invented by the day.

—Nor possibly my being invented, either.

You were in another day.You were beside me

and I saw you, like the snow,

asleep among the appearances.

Time, with no help from us,

invents houses, streets,

trees, and sleeping women.

While it’s true that all the theoretical speculation sometimes makes for a rhetorical voice even in Paz’s love poems (“being invented by the day”), I have often found this part of the pleasure of reading him; Paz makes poetry out of all the century’s isms and uncertainties, and from that poetry sometimes comes a calm certitude about love and wonder. It may be as complete, consistent, and universal an ontological statement as one finds in poetry in Spanish. Even if his depictions of the self and of linear time are unstable, this poetry posits that—whatever we are, however temporary, however jumbled our senses—love may save us from the world of illusions that hands us over, finally, to something mysterious, eternal, and ineffable.

Perhaps to address both those who admired him and those who burned his effigy, Paz held a public farewell in Mexico City. He would die a slow death from spinal cancer, his library having burned in an apartment fire—reminding him perhaps of his crumbling house during the civil war. As Krauze recounts:

He repeated his favorite metaphor of Mexico as “a country of the sun” but then immediately reminded the audience about the darkness of our history, our “luminous and cruel” duality that already reigned within the cosmogony of the Aztec gods and had been an obsession for him since childhood. He wished that some Socrates might appear who could free his people of the darker side, of all the destructive passions. . . . And suddenly he looked up toward the cloudy sky, as if he wanted to touch it with his hand. “Up there,” he said, “there are clouds and sun. Clouds and sun are related words. Let us be worthy of the clouds of the Valley of Mexico. Let us be worthy of the sun of the Valley of Mexico.” For an instant the sky cleared, leaving only the sun, and then Octavio Paz said, “The Valley of Mexico, that phrase lit up my childhood, my maturity, and my old age.”

7.

He had offered another sort of valedictory during the Cold War, this time in Spain, a nation recently emerged from fascism. It was the fiftieth anniversary of the Second International Congress of Anti-Fascist Writers. He recalled the controversy that was caused by Andre Gide’s 1937 report on the abuses and corruptions of power that had occurred under Stalin. The report made Gide a pariah on the literary left. When members of the Congress of Anti-Fascist Writers moved to censure Gide, Paz voted against it, but he didn’t speak out. At the fiftieth anniversary commemoration, Paz felt the need to confess. Though the censure was eventually vetoed by Andre Malraux, and Paz had been courageous to vote against it in the minority, he nevertheless regretted his behavior as a failure of the principle of fraternity. "Although many of us were convinced of the injustice of those attacks and we admired Gide, we kept silent," he said. "And so we contributed to the petrification of the revolution.”

My favorite poem in all of Paz’s oeuvre comes from that period of public repentance. One of his shortest, the poem indicates an awe in the face of our impotence, our smallness, our certain annihilation. It’s called “Brotherhood.”

I am a man: little do I last

and the night is enormous.

But I look up:

The stars write.

Unknowing I understand:

I too am written,

and at this very moment

someone spells me out.

Joel Whitney is a Brooklyn-based writer whose work has appeared in the New Republic, New York Times, Daily Beast, Wall Street Journal, Boston Review, and elsewhere. He is a founding editor of Guernica.