Cities in the Red: Austerity Hits America

Cities in the Red: Austerity Hits America

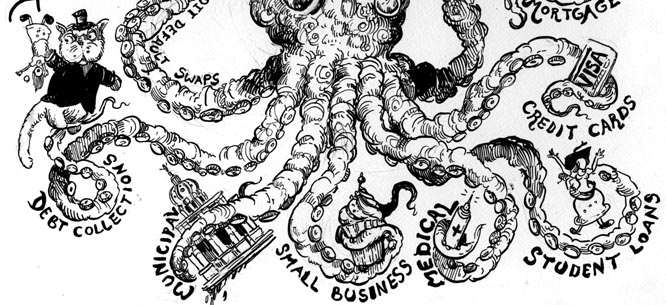

The cycle of debt illustrates that we cannot fix the problem through austerity. This tactic only deepens the devastation, since low wages further erode the tax base for cities, leaving them vulnerable to predatory lenders.

The European debt crisis, and the ensuing austerity-fueled chaos, can seem to Americans like a distant battle that portends a dark future. Yet a closer look reveals that the future is already here. American austerity has largely taken the form of municipal budget crises precipitated by predatory Wall Street lending practices. The debt financing of U.S. cities and towns, a neoliberal economic model that long precedes the current recession, has inflicted deep and growing suffering on communities across the country.

In July 2012, Mayor Christopher Doherty of Scranton, Pennsylvania, reduced all city employees’ salaries to the minimum wage. With a stroke of his pen, wages for teachers, firefighters, police, and other municipal workers, many of whom had been on the job for decades, dropped to $7.25 per hour. The city, the mayor explained, simply could not pay them more. Ron Allen, who reported the story for NBC Nightly News, repeated this assessment. Cities like Scranton, he said, “just don’t have the money” to pay city employees more than the minimum wage. Officials blamed the crisis on a declining tax base, on reduced revenue from the state, and on public sector labor contracts that the city could no longer afford.

What does it mean to say that a former steel town in decline “just doesn’t have the money” to pay its bills? It means that it no longer has access to credit markets controlled by the big banks. For years, Scranton officials, like officials across the United States, have been selling municipal bonds to finance everything from basic services to development projects. Scranton’s problems careened out of control when they city’s parking authority threatened to default on its bonds. Wall Street responded aggressively by cutting off its credit line, and city workers paid a steep price. American-style austerity arrived in Scranton under the guise of budget cuts blamed on public employees, whose salaries and pensions had nothing to do with the economic crisis.

Scranton’s problems are hardly unique. Municipalities across the country are grappling with declining local tax revenue and reduced federal funding in an era when growth and development are equated with prosperity. This toxic mix has produced a $3.7 trillion municipal debt market, a revenue juggernaut for Wall Street. Municipal bonds are issued by virtually every city, county, and development agency in the United States. The number of taxpayer-backed bonds in circulation is five times higher than only ten years ago. This means that the world’s largest financial firms now hold the purse strings for everything from essential services like sewage treatment plants to large-scale developments such as sports arenas. Municipal bonds are extremely profitable for investors because they are tax-exempt and, like mortgages, can be packaged into securities.

How Did We Get Here?

Part of the municipal debt story can be traced to New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis, when the city almost defaulted on its debt. New York was able to avoid bankruptcy at the last moment by issuing guaranteed bonds backed by public pension funds. As a result, the Emergency Financial Control Board, the municipal body that controlled the city’s bank accounts, was in the position of rewriting the social contract, exerting control over labor at every level. Union leadership agreed to the deal because they feared a bankruptcy filing would void labor contracts. Only after the city had disciplined the unions did the federal government move in with rescue loans.

New York City had been debt-financed since the 1960s. But the fiscal crisis of 1975 inaugurated a new funding paradigm for distressed municipalities: taxpayer-backed debt is issued to service the debt already on the books. American municipalities are now increasingly financed not with public money, but with private loans, and the pace of this shift has accelerated since 2008. The Center on Budget Policy and Priorities recently reported that thirty-one states will face unsustainable budget gaps in 2013.

Few public assets are safe from Wall Street’s profit imperative. Public transportation has long been a cash cow for investors. Since 2008, the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has lost over $600 million as a result of interest rate swaps with JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, and other big banks. As a result, thousands of transit workers have lost their jobs and hundreds of bus and subway lines have been cut. That is not enough to satisfy the bond market. In March 2013 New York transit riders can expect a new round of fare hikes. Most subway and bus riders are working-class New Yorkers, immigrants, and people of color. They will soon pay even more for the privilege of lining Jamie Dimon’s pockets.

The MTA is not the only municipal organization in the country that runs on debt. The Refund Transit Coalition, a public transportation advocacy group, has uncovered at least 1,100 of these swaps at more than 100 government agencies costing taxpayers $2.5 billion a year. None is more indebted than Boston’s Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA). The story is a familiar one: in 2000 state legislators ended most public subsidies for the MBTA, which was additionally saddled with almost $2 billion in debt, much of it left over from the infamous Big Dig. Wall Street was happy to provide loans so the MBTA could maintain the system’s aging infrastructure and finance expansions.

Twelve years later, Boston’s transit authority spends 33 cents of every dollar it takes in to service its debt. Lawmakers, who have learned the lessons of Scranton all too well, are unwilling to challenge Wall Street. Instead, they have proposed cutting services and raising fares by as much as 43 percent. No one believes this represents a long-term solution. As one Occupy Boston activist noted, “the MBTA has never even asked the banks and bondholders who continue to profit from the [transit system’s] enormous debt to take a similar cut, effectively giving the banks a ‘free ride,’ while forcing T riders—working people, the unemployed, students, seniors, and the disabled—to bear more of the burden.”

Increasing debt loads, along with other neoliberal policies demanding that municipalities do more with less, put cities under enormous pressure to promote private economic growth in lieu of spending public funds on public goods. This imperative is one reason that city officials have pursued controversial development strategies such as declaring a parcel of land “blighted” to allow it to be seized by eminent domain and auctioned to the highest bidder. For example, the Barclays Center, the new arena for the Brooklyn Nets, was built partially on land that was condemned before being transferred to a developer. Cities also generate revenue by leasing public assets to the private sector. In Chicago, for example, the Skyway toll road has been leased to a private company for ninety-nine years. Atlanta even privatized the city water supply, only to cancel the contract years later when residents complained about tainted water.

As the privatization of everything from land to transportation makes clear, taxpayers rarely have a direct say in which bonds are issued and which public assets are sold out from under them. But with municipalities guaranteeing loans by promising that bondholders will be repaid with tax dollars or revenue generated by the debt-funded project, taxpayers are often left footing the bill.

Meanwhile, it remains nearly impossible for municipalities to cancel bond deals. By law, most states cannot declare bankruptcy. And, in many cases, federal bankruptcy codes guarantee that creditors will be repaid. In 1994, Orange County, California declared bankruptcy to repair the damage done when its treasurer took out loans on behalf of the city and then lost $1.6 billion in the securities market. Following what was then the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. history, the county still paid its bondholders to avoid a tarnished credit rating. Another California city, Stockton, has been implementing severe austerity measures ever since the housing market tanked in 2008 in order to make payments to bondholders. The city cut 25 percent of its police officers, 30 percent of its firefighters, and over 40 percent of all other city employees. The crime rate in Stockton has skyrocketed and unemployment surged, and the city is now considering cutting pension benefits for retirees to pay its debts. The capital of the Golden State, Sacramento, has also cut its police force, by 30 percent, to fill a budget gap, and has seen a similar rise in crime—gun violence, rapes, and robberies have increased dramatically. Communities long ago abandoned by the state are also suffering from austerity. Camden, New Jersey, one of the poorest cities in the United States, recently privatized its police force, laying off officers and canceling union contracts. Today, the Camden police force often does not have the numbers to respond to crimes that don’t involve murder or serious injury.

As cities like Scranton seek to eliminate unsustainable debts, investors grow more demanding. Bond insurers involved in bankruptcy negotiations in Stockton and San Bernardino have even suggested that bondholders have a claim to CalPERS, the retirement fund for California’s public workers. Though the retirement system is constitutionally protected, this is a troubling development because bondholders’ demands are almost always given priority. A recent CBO report noted that “of the 18,400 municipal bond issuers rated by Moody’s Investors Service from 1970 to 2009, only 54 defaulted during that period.” Bonds are bets that banks don’t lose.

Though the debt financing of U.S. cities is not illegal, that doesn’t mean deals are made fairly and transparently. We recently learned that interest rates around the world have been manipulated for years for the benefit of a few firms. Yet the LIBOR scandal is not surprising when one considers that municipal interest rate fraud has been going on for years with no public outcry. In his report on municipal bond rigging in Rolling Stone, Matt Taibbi explained how Wall Street has “skimmed untold billions” from hundreds of municipalities—and how they continued to invest in bonds even after they were caught. “Get busted for welfare fraud even once in America, and good luck getting so much as a food stamp ever again,” Taibbi wrote. “Get caught rigging interest rates in 50 states, and the government goes right on handing you billions of dollars in public contracts.” The debt financing of municipal government is an activity promoted and protected by the regulatory arm of the federal government.

What Can Be Done?

Strike Debt, a group (of which I am a member) inspired by Occupy Wall Street, has begun to address municipal bonds as part of a larger critique of debt as a system of wealth extraction. Strike Debt asserts that debt is a primary mechanism through which the 1 percent profits from the 99 percent. Debt affects everyone, especially those who are too poor to access low-interest credit. And Wall Street is the primary culprit. Framing municipal debt as part of a global system poses significant opportunities for organizers because it connects anti-austerity movements abroad to debt resistance efforts at home. Once we reframe debt as a problem that affects us all—as municipal debt obviously does—it becomes easier to imagine that we have enormous power to withdraw our consent.

Strike Debt’s analysis of debt as a system of wealth extraction is also a critique of capitalism. Municipal debt is more than just another example of Wall Street greed and local corruption. It may be the biggest scandal yet because it is not a scandal it all. U.S. cities, towns, and districts are now increasingly debt financed, which means they cannot operate without access to the credit markets controlled by the big banks. This illustrates that Wall Street’s class war against cities cannot be mitigated with more regulation. In fact, the SEC protects investors, not municipalities, from the consequences of bond deals gone bad. Even renegotiating debt often requires new loans. “When muni bond issuers unwind deals and pay enormous exit fees to Wall Street,” the New York Times recently reported, “they typically issue new debt to do so. In recent years, for example, New York State has paid $243 million to terminate such transactions; $191 million was financed by new debt issuance.” Raiding cities for wealth, which produces a cycle of indebtedness, is not illegal or unusual. It is simply the way Wall Street does business.

The idea that some debts cannot and should not be paid is gaining traction. In 2011, for example, Jefferson County, Alabama declared bankruptcy (the largest in U.S. history) to rid itself of $4 billion in debt, much of it issued by corrupt officials to finance a sewer project that left people in a predominantly low-income, African-American community without a functioning sewer. Some do not want to renegotiate the debt. Instead, they reject it outright. As one Occupy activist in Birmingham noted, “[the debt] shouldn’t ever have been issued, and therefore it shouldn’t exist. It shouldn’t have been spent. Since it shouldn’t have existed, we’re not going to pay it.” This statement could become a slogan for debt resistance movements across the country because it insists that debtors are a class, a collective “we” that can decide when enough is enough.

Some municipalities are fighting back, too. After their pay was cut to minimum wage, Scranton’s municipal unions sued the city, and their wages were restored. Baltimore, a city where more than 80 percent of school children qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch, is suing more than a dozen big banks for manipulating LIBOR, the benchmark for interest rates on many financial products. In July, a group called Boston Fare Strike declared a Free Fare Day and held turnstiles open for subway riders to protest fare hikes that enrich the 1 percent. Activists in Chicago are organizing community debt audits with the goal of identifying illegitimate debts that must be abolished. And finally, in a case that has gained national attention, Oakland, CA is trying to sever its relationship with Goldman Sachs for good. In the late 1990s, Oakland issued $187 million in bonds as part of an interest-rate swap. After the credit markets froze in 2008, Oakland could no longer make its payments to Goldman. The city council voted to cancel the deal, though Goldman insists the city must pay. CEO Lloyd Blankfein explained his firm’s unwillingness to let Oakland out of its contract. “The fact of the matter is,” he said, “we’re a bank.”

Blankfein is not wrong. Plundering U.S. cities is what large financial firms do. This is a troubling reality. A bankruptcy attorney featured on the NBC News report about Scranton offered this grim assessment: cutting worker pay is necessary to avoid “more drastic measures.” The reporter didn’t explain this statement, leaving viewers to imagine what terrible fate awaits those who don’t accept the reigning neoliberal orthodoxy that city budgets must be balanced by cutting worker pay, gutting public services, and issuing more debt to profit the 1 percent.

In fact, it is Wall Street that should be afraid of any disruption to business as usual. The cycle of debt illustrates that we cannot fix the problem through austerity. This tactic only deepens the devastation, since low wages further erode the tax base for cities, leaving them vulnerable to predatory lenders. It’s difficult to imagine how the debt financing of American cities could be scaled back without completely rethinking our economic system. Strike Debt is making the case that, in the United States as in Europe, the solution lies not in austerity but in investing in a genuine commons and in providing equitable access to public resources. These are precisely the “drastic measures” alluded to on NBC News. The question we must ask is, drastic for whom?

Ann Larson is an organizer of Strike Debt. She is also a teacher, a writer, and a resident of Brooklyn.