A Place for Asia

A Place for Asia

Perhaps the ultimate irony is that in its critique of modernity and global capitalism, the Chinese New Left’s greatest tool has been neither market socialism nor anything native to China, but deconstructionism.

The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

by Pankaj Mishra

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012, 368 pp.

When renowned Harvard professor and economic historian Niall Ferguson paid a visit to the municipality of Chongqing in central China four years ago, he breathlessly declared the end of “Chimerica”—the symbiotic relationship between the U.S. and Chinese economies resulting from one’s propensity to spend and the other’s to finance that spending. He explained:

Nowhere better embodies the breakneck economic expansion of China than the city of Chongqing. Far up the River Yangzi, it is the fastest-growing city in the world today. I had seen some spectacular feats of construction in previous visits to China, but this put even Shanghai and Shenzhen into the shade. There was something truly awe-inspiring about the countless tower blocks under construction, the innumerable cranes perched on the city’s hills, the gleaming new highways, the brand-new enterprise zones, the ubiquitous smog. I felt I was witnessing an industrial revolution several orders of magnitude larger than the Industrial Revolution that once filled the cities of the West—of the British Isles and North America—with similar noxious fumes.

The Chinese New Left, whose ideas served as the foundation of Chongqing’s development, continues to return to this statement with pride. They fail to note, however, that Ferguson had immediately qualified his enthusiasm by saying the spectacle reminded him of the Soviet Union.

He makes a habit of dispensing such uneasy praise. In Civilization: The West and the Rest, Ferguson’s most recent book, he argues that the key to Western economic dominance in the twentieth century was “six killer apps,” which the rest of the world (i.e., China) is now downloading at the same alarming rate that the West is deleting them. Ferguson had, in the eyes of many, gotten carried away with the momentum of his pro-empire predilections, but his place at Davos remained secure.

Pankaj Mishra, acclaimed novelist and historian of Asia’s modern development, would have none of it. In a scathing essay published in the London Review of Books, Mishra gutted Ferguson for his dishonestly humanitarian portrait of Western imperialism and solipsistic lament of Western decline. Those charges, and the suggestion that Ferguson had a literary analogue in The Great Gatsby’s Tom Buchanan (who, also fearing his civilization was in danger, expressed white-supremacist ideas), launched a literary feud that culminated in Ferguson threatening to sue Mishra for libel.

Undaunted, Mishra expands on some of the themes of that debate in From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia. Unlike others who have offered sweeping assessments of the twentieth century’s influence on the global state of affairs, Mishra’s starting point, in this book and his earlier Temptations of the West: How to be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet and Beyond, is not the Cold War or the interplay of shifting economic relations and international realpolitik. Such currents, he believes, are important but given undue weight in Europe and America. For Mishra, the dominant narrative of the twentieth century for the majority of the world is “the intellectual and political awakening of Asia and its emergence from the ruins of both Asian and European empires.”

For this, Mishra credits the ferment of Asian intellectualism around the turn of the last century, exemplified by the work of Liang Qichao in China, Jamal-al-Din al-Afghani in the Islamic world, and Rabindranath Tagore in India. Though these figures are not the thinkers and activists the West would come to know once Asia more forcefully announced itself, they served as intellectual, political, and sometimes spiritual godfathers to their better known successors. Liang’s preoccupation with making China a powerful nation above all else influenced Mao Zedong’s vision for a Communist China and the Communist Party’s governance. The steadfastness of religious and cultural tradition within Islamic societies, an anomaly when all major powers have more or less become Westernized, traces its lineage to al-Afghani’s anointing of Islam as a source of national and geopolitical strength. Although Tagore is a little different from these two figures insofar as he was first and foremost a poet and spiritual leader, his critiques of capitalism and imperialism, based on Eastern philosophy and religion, were especially relevant in the wake of the First World War and continue to resonate today.

Mishra confesses that while these intellectuals’ legacies stand on their own merit, he found them particularly appealing subjects because of their lack of fame in the West. They are key figures in Asia’s pivotal cosmopolitan moment that go unrecognized in histories kinder to imperialism and more ignorant of developments with less immediate political results. As Mishra narrates their contributions to the shaping of our world, he is inviting us to adopt the East, not the West, as our vantage point.

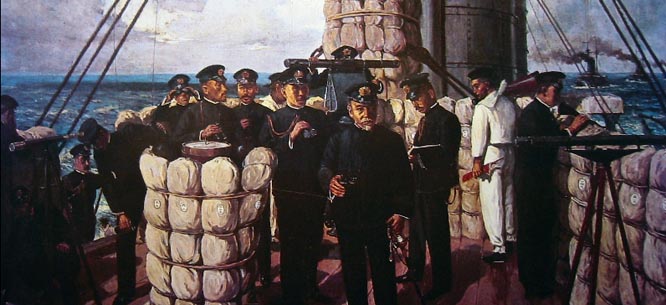

To drive this home, Mishra begins not with a colonial uprising but with the first sound military defeat of a Western power by an emerging one in Asia: the 1905 Battle of Tsushima. Indeed, Asia had never aspired to rebellion so much as the re-establishment of parity with, even superiority over, other foreign powers. By destroying Russia’s navy, Japan signaled to the rest of Asia that its imperialist oppressors were no longer invincible. The military victory captured the imagination of Asia’s intellectuals and spurred the production and dissemination of ideas that would eventually topple Western rule.

Somewhat to Mishra’s dismay, Asian intellectuals initially chose Western political and economic concepts as their preferred method of modernization, simply because they were the concepts closest to the seat of power during imperial rule. In Japan, that meant that Western-influenced constitutional reforms following the late-nineteenth-century Meiji Restoration were widely interpreted as the secret to self-strengthening. The reality, argues Mishra, was that the Japanese sociopolitical landscape was much better suited to republican government than that of other Asian countries. Ottoman Turkey, for instance, lacked Japan’s homogeneous population and history of secularism, and its modernizers had to contend with the ulema, a powerful, traditionalist group of religious elites. It also did not have the social organization needed to undertake the responsibilities of a Western-style government, nor the scientific advancement to fuel a self-sufficient economy, leading to even greater dependence on the West’s resources and guidance. (To remain fair, Mishra grants that the desire of some Asian leaders to use modern infrastructure to enhance their despotic agendas further undermined its potential.)

Even where concrete reforms did not pan out, Asian intellectuals became permanently fixated on Western economic and political theory. The Chinese who studied in Japan in the late 1800s to early 1900s, for example, learned about democracy, capitalism, and communism and debated their applicability to China. Any intellectual who wanted to be a part of the conversation, even those of more traditional or essentialist persuasion, became fluent in the language of Hegel, Marx, Weber, and John Stuart Mill, among many others. Asia’s intelligentsia believed ideas, more than socioeconomic circumstances, were the heart of Western power. Perhaps it was due to the experience under colonial rule of constantly needing to question the nature and legitimacy of their existence that Asian people gravitated toward thinking in terms of fundamentals.

However, completely breaking with tradition was not as attractive to these thinkers as adapting Western ideas to traditional Asian culture. Even if some sort of republicanism or democracy was the long-term goal, their immediate objective was to ensure that a strong state, the necessary condition for modern governance, was in place. In some cases, intellectuals sought to reconcile their societies’ own foundational ideas to those from the West, arguing that the two bodies of thought were, when framed correctly, very much compatible, even alike. Al-Afghani shrewdly realized that imitation of the West would do nothing for Muslim confidence, and so he reinterpreted Muslim tradition to emphasize rationality and a history of scientific discovery and inquiry by scholars in Baghdad and Persia. Both the Young Ottomans and the Chinese announced that the Koran and Confucius, respectively, called for the protection of individual rights.

If it seems as though Asian intellectuals had an unapologetically instrumental view of Western ideas, Mishra certainly does not view this as a shortcoming. Indeed, he has stated several times in the course of promoting the book that these men were “thinkers on the run,” more inclined to activism and pragmatism than theoretical completeness because of the exigencies of their situation. Although the reactionary nature of Asia’s intellectual development was a reasonable response to the dire conditions they faced, we ought to remember that many of Europe’s grand systems of thought originated during times of revolution and war. Yet Mishra does not acknowledge them as similarly pragmatic responses to historical circumstances. If it is true that social, political, and economic forces are responsible for the West’s and Asia’s different philosophical approaches to difficult situations, he has not yet made that case. (In that sense, Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia, the subtitle of the book in the United Kingdom, is much more fitting than the American one.)

Of all the ideas from the West that gained traction in Asia, none was more influential than Social Darwinism. The imperative to survive the natural selection process was considered the one immutable law, and geopolitical power dynamics seemed to bear out the importance of relative strength. As a result, the ability to confront and gain independence from the West became the ultimate metric of success. What Asian leaders would do in the name of Social Darwinism had to be acceptable in the prevailing intellectual climate—not a difficult threshold to meet when Asia was constantly looking for a way to completely rework its underpinnings. Mishra is understandably less than enthusiastic about this perspective given that it eventually led to almost wholesale importation of Western society, warts and all. But he does not recognize that this attitude is in tension with his admiration for intellectuals who abandoned the difficult task of reform by ideas for the satisfaction of forceful self-assertion.

Perhaps it was only a natural consequence of their results-driven approach that Asia’s intellectuals eventually divorced Western ideas from their actual content and married them to their most prominent application. It was in this spirit that communism would take hold throughout Asia after the October Revolution overthrew the Russian Empire. Lenin’s call for action against imperialists, predicted Benoy Kumar Sarkar, an Indian sociologist, would cement the Soviet Union’s place as a friend to oppressed Asian nations desperately looking for an ally in the West and communism as Asia’s most popular path to self-governance, “and this independently of the consideration as to the amount of progress that the anti-propertyism of Bolshevik economics is likely to achieve among the masses and intelligentsia of Eastern Asia.”

Real-world events eventually led to Asia losing its enthusiasm for Western ideas. The awesome destruction and bloodshed of the First World War instilled serious doubts about the true benefits of modernism and the domination of science. A few years prior, Liang Qichao was so unimpressed with the state of democratic politics at the national level in the United States that he concluded not even it—let alone China—was completely ready for democracy.

Cognizant of their proud past and disillusioned with the outcomes of Western experimentation, Asian thinkers turned to neo-traditionalism after the First World War. Thinkers in China and India came to believe that the anti-materialism and spirituality of traditional Eastern thought was a necessary tempering influence, if not a superior substitute, for the ideas and methods underpinning Western modernity. Tagore, in particular, staked the salvation of Asia on “a deeper transformation of life, in the liberation of consciousness in love, in the realization of God in man.” Spreading his message on international lecture tours, he found that the West and India were much more receptive than China, where the rapid industrialization of the Communist Revolution was gaining momentum.

Fundamentalist groups in the Islamic world took neo-traditionalism one step further and rejected much of the narrative of Western modernity. These ideas have culminated in the establishment of states and mainstream political entities like the post-revolutionary Iranian government and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Mishra rightly criticizes Islamic fundamentalism, but his condemnation is hardly as decisive as the one directed at exploitative Western imperialist powers. Though he builds a sympathetic case for the radicalization of the Islamic world, it is hardly a given that acts of desperation are on their face more justifiable than those done out of a “will to power.”

It speaks to the magnitude of the rush of historical events during Asia’s intellectual renaissance that the most insightful self-reflection in Mishra’s book comes at the very end. Even then, he does not express much more than a deep ambivalence about the negative externalities of modernization—social inequality, environmental degradation, and the political tinderbox built upon the two. Mishra recognizes that one of the great failings of the Asian intellectual project has been its inability to come up with an original set of universal principles that can answer those from the West. He does not, however, quite appreciate just how significant this deficiency is, or that if it had been corrected earlier in the process, the shortsightedness of the “as much of a Western-style society as ours will allow” strategy may not have left the legacy of ideological gaps and harmful byproducts of hyper-industrialization that Asia faces today.

If it is true that Asia’s emerging countries are repeating the mistakes of Western modernity, then perhaps the idea of modernity, in the sense of linear development based on liberalism and scientific progress, should itself be reconsidered. From the Ruins of Empire is the culmination of Mishra’s efforts to write a history of Asia as significant as the ones included in Western texts. But its greater contemporary contribution comes from the fact that, in Mishra’s words, we face “a deep crisis of modernity in general.”

It is a moment that the Chinese New Left, and especially Wang Hui, its leading intellectual, senses. In 2006 Mishra met Wang in Beijing and profiled his work and that of his colleagues for the New York Times. Their friendship and exchange of ideas have continued to flourish, but Mishra still feels a bit uneasy that Wang was dismissed from the editorship of Dushu, China’s preeminent literary journal, soon after that profile was published. The Chinese New Left, led by Wang, Cui Zhiyuan, Wang Shaoguang, and Gan Yang, has faced other setbacks in the last few years. China’s leadership has at most paid lip service to their concerns about rising income inequality and the rampant poverty in China’s rural areas, and Bo Xilai, their most prominent voice among China’s ruling elites, has been expelled from the Communist Party and will shortly face prosecution. Whatever their status in the marketplace of ideas, the Chinese New Left perform an invaluable role in defining China’s organic uniqueness as a political and socio-economic unit. Unlike the liberal democrats and free-marketeers on the right, they strongly believe in the urgency and timeliness of contributing to modern thought. Globalization’s imbalances and political decay are the latest in a long line of historical developments that reveal modernity to be the most fragile component of the West’s foundations. Asia’s intellectuals sense that if they can make their mark on this cornerstone, they can assert intellectual parity, if not primacy.

Perhaps the ultimate irony is that in its critique of modernity and global capitalism, the Chinese New Left’s greatest tool has been neither market socialism nor anything native to China, but deconstructionism. Granted, the Chinese do not call it by this name; they have not even begun to exhaust Hegel. However, Wang’s analysis could not be clearer: “The anti-modern modernity is no longer simply a unique expression of Chinese thought, but is also an expression of the contradictory structure of modernity itself.” The current method of intellectual sparring with the West is not direct confrontation so much as the discovery of possible points of implosion. Wang Shaoguang’s redefinition of democracy as a combination of “responsibility, responsiveness, and accountability,” and not just a government by free elections, which are often undercut by perverse incentives, has become popular in China. Behind the sentiment is a distinct desire to beat the West at its own game by implying that the Chinese social experiment has better fulfilled the ideals of Western liberalism.

The new approach is not as frivolous as it sounds. Both Cui and Wang draw on ancient Chinese teachings of Buddhism and Taoism to resurrect the idea that anything universal like modernity is embodied in very particular circumstances, and these circumstances in turn reveal what is universal. At the same time that the Chinese intelligentsia is aiming to escape the framework of Western modernity, it wants to make sure that China is still considered to be part of the larger story of the modern world. There is a certain fear that China will lose its hard-earned place in history or fail to learn valuable lessons from the West’s experience of modernity if they do not work within its existing structure.

The enemy of colonialism is mostly gone, yet Asia is unsatisfied with its progress. Many of the questions the West’s rise posed about the nature of statehood, the existence of universal rights, and the elusiveness of intellectual integrity in the face of a framework as dominant as modernity are still valid today. Modernity may have been the motivating antagonist in the history Mishra so thoroughly and thoughtfully documents, but never has it been so close to Asia as it is now—not knocking on its doors anymore, but invited as a permanent guest. Mishra’s lament of Asia’s inability to create universalisms with the “prestige and authority of Western modernity” is on its way to becoming moot, as intellectuals experience a level of self-consciousness they were previously spared because, unlike in the West, there was not yet a sense they had reached the end of their history.

The gravest way Asia can be wronged at this juncture is to take away the promise of indefinite and limitless possibilities, particularly when the developed world is not hiding its perception of its own paralysis. Despite his considerable achievement, Mishra gives the sense that he hopes Asia will prove his pessimistic conclusions wrong and his historical narrative rather quaint. For the first time, it is Asia’s responsibility, and not simply its right, to hope so too.

Rebecca Liao is an attorney and critic based in the Silicon Valley, founder of The Aleph Mag, and contributor to Tea Leaf Nation and the LA Review of Books.