The Ethics of Alliance and Solidarity: An Exchange Between Rafia Zakaria and Meredith Tax

The Ethics of Alliance and Solidarity: An Exchange Between Rafia Zakaria and Meredith Tax

The following is an exchange based on a recent Dissent article by Meredith Tax. To take part in the debate, you can visit Dissent’s Facebook page.

In her essay “An Expedient Alliance? The Muslim Right and The Anglo-American Left,” noted feminist Meredith Tax makes a number of accusations. Most of them center on the Left’s “support of the Muslim Right,” which has in Tax’s view “undermined struggles for secular democracy in the Global South.” Tax argues that “left-wing alliances with fundamentalist groups” amount to a betrayal “of the majority of their co-religionists, who do not wish to be represented by extremists.”

As someone whose native country of Pakistan is currently ravaged by the Tehreek-e-Taliban and a motley of affiliated groups, who has lost friends to mobs led by religious bigots, and who fears being unable to return to a beloved homeland, I could not share more wholeheartedly Tax’s assessment of the virulence of fundamentalism and the threat it poses to free expression, to women, to minorities, and to all those who oppose the imposition of their views on others. Fundamentalism is devastating diverse societies and inflicting blows on long-sustained histories of pluralism and tolerance.

However, I was deeply disturbed by the breadth of the claims and denunciations in Tax’s piece. Tax erects her architecture of left-right support and alliance with a series of anecdotes. These include, among others, state “multiculturalism” policies in the UK that have led to funding for “identity-based groups associated with the Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat e Islaami,” antiwar activists’ support for the “Iraqi insurgency,” and an “unwillingness to criticize the Iranian theocracy.” Each bit provides a glimpse of an actual controversy, but only the bit suited to Tax’s purposes: underlining the Left’s stupidity when it comes to dealing with political Islam. Any geographical, cultural, or contextual complications that don’t fit the rubric of the stupid Left and the sly Muslim Right are discarded.

The variety of brief examples establish points that most leftists would agree with, making it harder to examine the reductions and conflations they contain without losing the forest for the trees. I could point out, for example, that Sharia is not a static body of law but a dynamic body of jurisprudence open to reinterpretation. Or I could direct readers to the brave feminist interventions that are beginning the task of taking Sharia from avowedly discriminatory and patriarchal uses to the feminist and egalitarian ones.

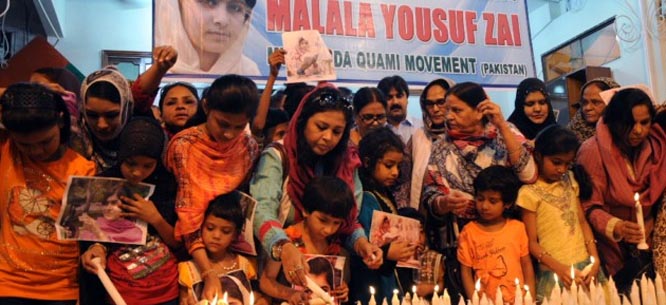

In my own selection of anecdotes, I would also include the story of Asiya Nasir. A female, Christian MP in the National Assembly of Pakistan, Nasir’s party is none other than the Jamaat Ulema Islam, which by Tax’s definitions is part of the “Muslim Right.” Nasir is one of the strongest advocates for minorities and women in Pakistan, battling criticism from all sides to push human rights issues onto the parliamentary agenda. I could even take Tax’s own example of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl who was shot by the Taliban while sitting in her school bus. While Yousafzai is a champion of girl’s education, she keeps her head covered and prays in nearly every interview, she hasn’t come out in favor of gay rights or a secular state, and a group of Pakistani Islamists have issued a fatwa that denounces the Taliban attack and comes out in favor of girls’ education. Does all this disqualify Yousafzai from the support of the Anglo-American Left?

Ultimately, the anecdotal arguments in Tax’s piece serve to create a broad binary that seeks to divide up good and bad Muslims (along with good and bad leftists). It blinds us to the possibility that there are crucial differences between the identity politics of minority Muslims in the United Kingdom and the inner divisions among Islamists in Pakistan, between the insurgency in Iraq and the politics of the Brotherhood in post-Mubarak Egypt. Tax elides these differences and uses a single recipe for denunciation, which applies to “those the media call ‘moderate Islamists’” just as much as it applies to al-Qaeda.

Finally, there is the question of alliance itself. In a world where multi-dimensional allegiances and prismatic identities have left many alienated; the idea of rallying the Anglo-American Left around some central principles—including the separation of church and state—is a well-intentioned one. But Tax uses this rallying cry to blame leftists for “undermin[ing] struggles for secular democracy in the Global South.” There is hubris in this argument—in the idea that the political trajectories of the Global South are dependant on the ruminations of Anglo-American leftists and their ability to choose the right alliances. Political ideas and movements in the Middle East and South Asia do not generally rise and fall on such questions. Moreover, the secular and liberal Obama administration’s drone campaign has done far more to motivate religious extremism in Pakistan than Code Pink’s decision to work with Imran Khan and his Islamist political party.

Tax’s essay could have provoked some necessary soul-searching on the American Left about the meaning of solidarity and support at a time when the American government is engaged in globe-spanning conflict with Islamic extremists, but it reads as an angry tirade against insufficiently emphatic denunciations. As a Pakistani and American living at the intersection of two societies mired in mistrust, in which all interactions are immediately elevated to civilizational consequence, I would argue that a dialectic of compassion would serve us better than attack. Such a dialectic would not force us into the crude choices of identity politics (are you a Muslim or woman first?) or into either/ors over contested concepts like Sharia, but rather acknowledge that humans ally and interact politically on multiple levels, that common understanding is slow, and that the rhetoric of denunciation can create distance between the very people who would most benefit from any alliance at all.

Meredith Tax Replies:

Rafia Zakaria and I have a number of points of agreement. We agree on the dangers of fundamentalism. We agree that some feminists are trying to make Sharia more woman-friendly and that Sharia is not a static body of law; my book Double Bind quotes Women Living Under Muslim Laws to say that “there is no such thing as a codified Sharia.”

We disagree on other points. Zakaria objects to my critical tone and my use of examples, which she calls “anecdotes,” saying, “Each bit provides a glimpse of an actual controversy, but only the bit suited to Tax’s purposes: underlining the Left’s stupidity when it comes to dealing with political Islam.” Exactly. I chose examples that would illustrate the point I was trying to make and point to a deeply problematic trend of support by certain left-wing groups for the Muslin Right—a trend many others have also noted, including Fred Halliday.

To my examples Zakaria opposes two of her own. The first is Asiya Nasir, described as a Christian woman MP belonging to an Islamic party in Pakistan, Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUL-F). Despite Nasir’s membership in this party, Zakaria says she is a strong advocate for women and minorities.

But Zakaria leaves out a plot point: why would a group that has been described as a “hard-line Islamist party, widely considered a political front for numerous jihadi organizations, including the Taliban,” a party that believes women should have no part in public life, want a Christian female MP to begin with? The answer is political opportunism. Pakistan reserves 17 percent of its seats in parliament for women and dishes them out according to each party’s number of votes. Since 2002 all candidates have had to be college graduates. Most members of the JUI-F were educated in madrassahs rather than secular universities, so when they got seven votes in the 2008 election and were awarded an additional seat for a woman, they had to scramble for a candidate.

Asiya Nasir’s membership in the JUI-F has in no way mitigated its anti-woman politics. As Afiya Zia of Pakistan’s Women’s Action Forum points out, the entire JUI-F party actively opposed last year’s Domestic Violence Bill. Its leader, Maulana Fazlur Rahman,

dismissed the Bill’s contents as an attempt to impose a Zionist/Westernised agenda and its proponents as ‘home-breakers and shameless women’….The women members of the JUI-F also expressed their objection to the ‘freedoms’ associated with the DVB, which, in their view, challenges the sanctity of marriage and the rightful dominance of the husband. According to them, domestic violence is often an impulsive act on part of the husband when the woman tries to become head of the household.

So much for Zakaria’s first example. Her second is Pakistani schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai, of whom she says, “While Yousafzai is a champion of girl’s education, she keeps her head covered and prays in nearly every interview, she hasn’t come out in favor of gay rights or a secular state.”

But Malala Yousafzai, like her father, is an activist for secular education and against fundamentalism. The Talibanis who shot her say they did so because she wanted to secularize society and because she spoke against them. “We did not attack her for raising voice for education. We targeted her for opposing mujahideen and their war.” However personally observant she may be, politically she risked her life to advocate for the separation between religion and the state—the very meaning of secularism, and the only secure basis for the rights of women, religious minorities, sexual minorities, and dissenters. Why confuse the issue?

Zakaria also objects to my lumping “moderate Islamists” and Salafi-Jihadis together as members of the Muslim Right. Many in the human rights world were willing to take “moderate Islamist” parties like Ennadha in Tunisa and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt at face value when they said they opposed violence and believed in democracy. But now that these parties are in power, violence and repression are increasing. Sexual assaults on women in Tahrir Square have become so overwhelming that Egyptian protesters are forming their own protection squads, while in Tunisia, Chokri Belaid, a secular opposition politician, was assassinated last month and his widow holds Ennadha responsible. Ennadha’s neoliberal economic policies have also led to pitched battles between party militants and trade unionists, while the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt just released a statement calling on all “Islamic countries” to oppose CEDAW because it “violates all principles of the Islamic Sharia and the Islamic community.”

Similarly in Bangladesh, members of the “moderate Islamist” party Jamaat e Islami have been engaged in a bloodbath since one of their leaders was condemned to death on February 28 for crimes against humanity committed during the 1971 War of Independence. In the twenty-four hours after the verdict, at least thirty-five people were killed; subsequently, Hindu neighborhoods were attacked and a train full of Hindus set on fire. A delegation supporting justice for genocide victims visited Amnesty International in London, asking for support for demands made by the Centre for Secular Space including “an investigation into the threat to human rights constituted by global religious fundamentalist organisations such as the Jamaat e Islami.”

Unfortunately, anyone who mentions facts like these is likely to be accused, in Zakaria’s words, of creating “a broad binary that seeks to divide up good and bad Muslims.” But these conflicts are real and Muslims are fighting on both sides. So whom are we to have solidarity with—trade unionists, feminists, gays, and students, or the “moderate Islamists” in power? Attempts to blur this question will not make it go away.

But Zakaria says that those in the North don’t have to worry about these matters because it is hubris to imagine that “the political trajectories of the Global South are dependant on the ruminations of Anglo-American leftists and their ability to choose the right alliances.”

To me, thinking on a global scale is not hubris; it is a strategic necessity in a globalized world where, more than ever before, actions in one place affect events in another. Think how the protesters of Tahrir Square and the indignados of Spain created a feedback loop with Occupy. Knowing and caring what is happening to people in other parts of the world is neither rescue nor interference; it is mutual aid and common interest, particularly for those with a similar vision of social change. I do not mean some vague and fuzzy “dialectic of compassion” but good old-fashioned solidarity.

One way of showing solidarity is to draw attention to the demands of movements in other places. In that spirit, here is part of the International Women’s Day statement of the Women’s Action Forum of Pakistan, written in response to Sunni violence against the Shia minority.

We demand that militant religious organizations face public criminal prosecution through due process of law….The impunity with which these terrorists operate must be revoked and their funding sources halted, including the detrimental role played by some Saudi Arabian interests groups….

We demand that the Pakistan army and paramilitary forces be made answerable to civilian authorities and accountable to citizens to explain their performance in the ‘war against terror’ for which it has received funds from America, in addition to a significant share from the national budget….

We mourn and condemn the countless precious lives lost to terrorism. We believe the way out is to be found within the Constitution and democracy. WAF reiterates the necessity of a secular dispensation. WAF urges for a substantive peace that offers justice and protection of human rights and liberties for all citizens. We believe it is possible.

Rafia Zakaria is a columnist for DAWN, Pakistan’s largest English-language newspaper. She is an attorney and human rights activist and the author of Silence in Karachi, forthcoming from Beacon Press.

Meredith Tax is the author of Double Bind: The Muslim Right, the Anglo-American Left, and Universal Human Rights. She is a writer and activist, and chair of the board of the Centre for Secular Space.