Spain Rodriguez (1940-2012)

Spain Rodriguez (1940-2012)

We are now so far from the 1960s and ’70s that the crucial locations, personalities, and moments of one very popular art form’s transformation have been largely forgotten. Spain Rodriguez, with a handful of others (the best remembered are happily still with us: Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, Kim Deitch, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, and Sharon Rudahl, to name a few), pushed the comics agenda so far forward that no return to the limitations of superheroes and banal daily newspaper strips would ever be possible. Comic art, belatedly recognized in the New York Times (and assorted museums) as a real art and not a corrupting children’s literature, owes much to them.

We are now so far from the 1960s and ’70s that the crucial locations, personalities, and moments of one very popular art form’s transformation have been largely forgotten. Spain Rodriguez, with a handful of others (the best remembered are happily still with us: Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, Kim Deitch, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, and Sharon Rudahl, to name a few), pushed the comics agenda so far forward that no return to the limitations of superheroes and banal daily newspaper strips would ever be possible. Comic art, belatedly recognized in the New York Times (and assorted museums) as a real art and not a corrupting children’s literature, owes much to them.

Spain (his birth name was Manuel, his father a Spanish immigrant, his mother an Italian-American artist) grew up in Buffalo, New York, a rebellious working-class kid who wore long sideburns and was impressed by the civil rights movement. He dropped out of art school in Connecticut and, after returning to Buffalo and working a factory job with a motorcycle gang engagement, landed in New York in time for the efflorescence of Underground Comix (styled with an “x” to distinguish itself) in a comic tabloid offshoot of the East Village Other. His colleagues were a strangely mixed crew, all of them old enough to have been influenced by EC Comics, the most politically liberal and artistically accomplished of the old comics industry, and the one hardest hit by the congressional hearings of the McCarthy era. (As with attacks on the Left, every charge of subversion and perversion hid Middle-American outrage: these were Jews corrupting innocent American youth.) In a sense, every “underground” artist of these early days sought revenge in the name of comic art, and realized it through the depiction of sex, violence, and anti-war and anti-racist sentiment unthinkable in what remained of the mainstream. Sex and violence, lamentably, became chief attractions to many readers, recalling the “headlights” (aka “sweater girl”) crime and horror comics of the late 1940s, albeit with a left-wing or libertarian ambience.

The whole comix artistic crowd moved to San Francisco around 1970, joining Robert Crumb and a few others already there, part of the acid-rock, post–Summer of Love setting. Underground comix, replicating the old kids-comics format but now in black and white, grew up alongside the underground press, whose reprinting of comix created the market for the books. Crumb was the artist whose work sold the best, in the hundreds of thousands, but Spain was widely regarded as the most political. He was heavily influenced by the most bohemian of the EC comics world, wild man Wallace Wood, whose sci-fi adventures depicted civilizations recovering from atomic war and whose Mad Comics stories assaulted the 1950s commercialization of popular culture. Wood’s dames were also extremely sexy, too overtly sexy for the diluted satire of the later Mad Magazine.

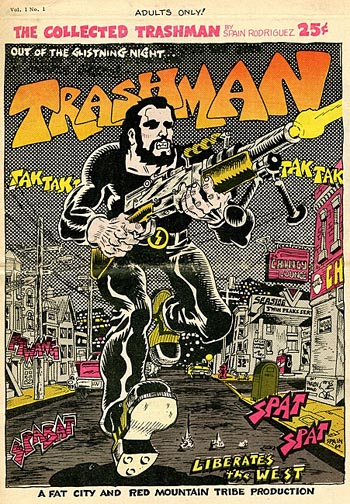

Trashman: Agent of the Sixth International was Rodriguez’s signature saga in these early years, serialized in underground papers, comix anthologies, and eventually collected in comic book form as Subvert Comics. These revolutionaries took revenge on a truly evil American ruling class in assorted ways, many of them violent, but they also had fun and sex, and were subject to many self-satirizing gags, in the process. By the middle 1970s, his work had broadened into more social and historical themes, often with class, sex, and violence highlighting his points. Histories of revolutions and anti-fascist actions (and all their complexities) inspired some of his closest reading of real events, but he had no fixed point on the left-wing scale. He admired and drew about anti-Bolshevist anarchist leader Nestor Makhno also anti-Stalinist Spanish anarchist Durruti, but he also drew about Red Army members facing death fighting the Germans, and so on. (Several of these pieces are now reprinted in Anarchy Comics: The Complete Collection, an anthology from that 1980s series, just published by PM Press.)

In recollections of the internal conflicts among comix artists, sometimes pitting feminists against male-dominated circles, Rodriguez is remembered as having been unusually helpful and egalitarian, a memory that contrasts curiously with his sometimes sado-masochistic plot lines but not so curiously with the gender-equality of the sybarites (“Big Bitch” was Trashman’s female counterpart, the tough working-class broad with sex cravings for weaker men). He poked and prodded San Francisco’s self-image as a haven of liberated sex, sometimes making his younger self a player on the scene. He also helped set in motion the vital murals movement in San Francisco’s Mission District, but was likely best known on the West Coast for his many posters of San Francisco Mime Troupe openings.

The validation of comic art from near the end of the century onward—Spiegelman’s Maus and left-wing lesbian Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home high among the evidence of artistic achievement—found Rodriguez with a Salon series, “The Dark Hotel,” and several books of his own. Devil Dog, a biography of disillusioned Marine Corps general Smedley Butler, and Nightmare Alley, an adaptation of the classic noir novel, are easily among the best. Che, his graphic biography of Che Guevara, reached the furthest, with editions published everywhere from Latin America to Europe, Japan, and Malaysia. At the time of his death, Rodriguez was amid “Yiddish Bohemians,” a strip about Jewish-American puppeteers during the 1920s and ’30s, in what would be the last in a stunning series of collaborations with playwright-professor Joel Schechter. Rodriguez had started a Woody Guthrie poster for an upcoming Bay Area concert and, had he lived, would have drawn a history of the 2003 San Francisco hotel strike.

After more than forty years (and the disappearance of well over 90 percent of many little-remembered artists’ work in yellowing pulp), the impact of the Underground Comix world remains more a matter of style than substance, daring more than narrative and artistic content. This is unfortunate, because so many artists had particular contributions worthy of note, worthy of reprinting for the sake of comic art alone. Spain Rodriquez lasted long enough to see his work in square covers (if not often hard covers), his unique and quasi-realistic modernism preserved for generations ahead. That he never lost his political vision or his sense of humor should go without saying, but those of us lucky enough to see him teach or to be taught by him felt the deep impact of his humanism as well.

Rodriguez died at home in San Francisco, with his wife, Susan Stern, a documentary filmmaker, and his daughter, Nora Rodriguez, by his side. A retrospect of his work, including a short documentary film made by his wife, is now in place at the Burchfield Penny Art Center in Buffalo, the second exhibit in Buffalo to honor this improbable local hero.

(Paul Buhle was the editor of Che and is co-editor of the anthology Bohemians, to appear in 2013, with two strips by Rodriguez.)