Trickle-Down Feminism

Trickle-Down Feminism

While we debate the travails of some of the world’s most privileged women, most women are up against the wall. And yet for much of mainstream feminist discourse, it’s as if the economy hasn’t shifted, or as if there’s nothing about it worth examining from the standpoint of gender.

If you read what is popularly known as the feminist press, you’ll notice a focus on the “glass ceiling” that excludes much else. Feminist writers are found celebrating the achievements of Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg, cheering Christine Lagarde’s position at the International Monetary Fund, wringing their hands over Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer’s refusal to call herself a feminist, or asking, as Anne-Marie Slaughter did in the pages of the Atlantic, whether (white, well-off, educated) women can “have it all.”

While we debate the travails of some of the world’s most privileged women, most women are up against the wall. According to the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, women make up just under half of the national workforce, but about 60 percent of the minimum-wage workforce and 73 percent of tipped workers. In the New York area, a full 95 percent of domestic workers are female. Female-dominated sectors such as retail sales, food service, and home health care are some of the fastest-growing fields in the new economy, and even in those fields, women earn less; women in the restaurant industry earn 83 cents to a man’s dollar.

This is where most women spend their time, not atop the Googleplex. This is where feminists should be spending their time, too.

The stakes are clear. Domestic workers, home care workers, nurses, and other largely female contingents must organize their workplaces or the work that most women do will continue to be undervalued, virtually unregulated, and precarious. The deunionization that has left about 88 percent of American workers without unions will drag the rest of us down as well.

And yet for much of mainstream feminist discourse, it’s as if the economy hasn’t shifted, or as if there’s nothing about it worth examining from the standpoint of gender. As uprisings in Wisconsin and Ohio over union rights rocked the country, as a movement for economic justice took to streets and parks around the world, I watched feminist writers seem to give a collective shrug. As Laurie Penny wrote in the New Statesman, “While we all worry about the glass ceiling, there are millions of women standing in the basement—and the basement is flooding.”

And yet for much of mainstream feminist discourse, it’s as if the economy hasn’t shifted, or as if there’s nothing about it worth examining from the standpoint of gender. As uprisings in Wisconsin and Ohio over union rights rocked the country, as a movement for economic justice took to streets and parks around the world, I watched feminist writers seem to give a collective shrug. As Laurie Penny wrote in the New Statesman, “While we all worry about the glass ceiling, there are millions of women standing in the basement—and the basement is flooding.”

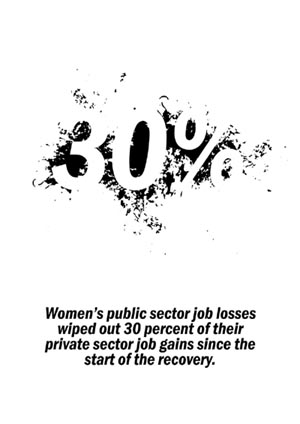

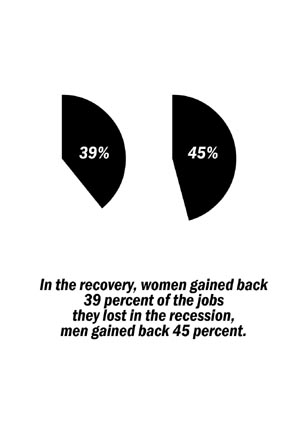

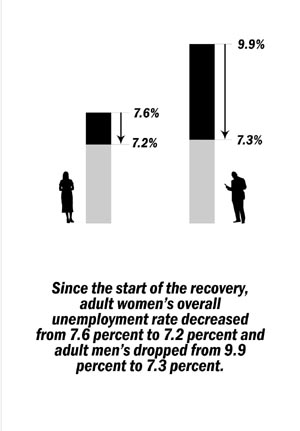

The brave new economy being rebuilt in the wake of the financial meltdown is being built on low-wage service work, as manufacturing’s decline has accelerated and construction ground to a halt. At the beginning of the Great Recession, economist Heather Boushey noted at Slate, manufacturing and construction made up fully half the jobs lost, along with financial services and other business fields, and writers declared the “Mancession” or “He-cession” or even, as Hanna Rosin’s popular book has it, The End of Men. But as others have pointed out, as the recession drags on, it’s women who’ve faced the largest losses, not only in direct attacks on public sector jobs that are dominated by women, but in increased competition from the men pushed out of their previous professions. Some 60 percent of the jobs lost in the public sector were held by women, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. And women have regained only 12 percent of the jobs lost during the recession, while men have regained 63 percent of the jobs they lost.

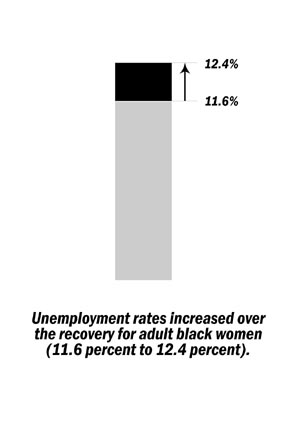

Women may be overrepresented in the growing sectors of the economy, but those sectors pay poverty wages. The public sector job cuts that have been largely responsible for unemployment remaining at or near 8 percent have fallen disproportionately on women (and women of color are hit the hardest). Those good union jobs disappear, and are replaced with a minimum-wage gig at Walmart—and even in retail, women make only 90 percent of what men make.

“All work is gendered. And the economy that we have assigns different levels of value based off of that,” says Ai-Jen Poo, executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance. Poo came to labor organizing through feminism. As a volunteer in a domestic violence shelter for Asian immigrant women, she explains, she realized that it was women who had economic opportunities who were able to break the cycle of violence. She brings a sharp gender analysis to the struggle for respect and better treatment for the workers, mostly women, who “make all other work possible.”

Women may be overrepresented in the growing sectors of the economy, but those sectors pay poverty wages.

“Society has devalued that work over time,” she notes of the cleaning, caring, cooking, and other work domestic workers perform, largely hidden from public view, “and we think that that has a lot to do with who’s done the work.”

This argument was at the root of the fight for access to employment outside of the “pink-collar” fields. To be trapped in women’s jobs was to be forever trapped in a certain vision of femininity. Breaking out of “women’s work” was a form of breaking through the “feminine mystique” that Betty Friedan decried. But that work still needs to be done, and, Poo notes, the conditions that have long defined domestic work and service work—instability, lack of training, lack of career pathways, low pay—are now increasingly the reality for all American workers, not just women. When we focus on equal access at the top, we miss out the real story, which historian Bethany Moreton points out, “is not ‘Oh wow, women get to be lawyers,’ but that men get to be casualized clerks.”

Employers have relied not just on being able to pay women less, but on specific gendered skills and qualities that they expected from female workers. Moreton, in her book To Serve God and Wal-Mart, detailed the way that the retail behemoth exploited the specific skills of Southern white Christian women going to work outside the home for the first time as much as their willingness to work for little pay because they’d never been paid before. The tradition of service that those women grew up with kept them working in low-wage jobs and made it hard for them to see the gender discrimination happening before their eyes—until, that is, a few of them sued.

The conditions of women at the bottom of the economic ladder have had an impact on everyone, as the middle rungs have weakened or disappeared. Using the excuse of “care” to pay women less drove wages down, and now those jobs make up more and more of the economy, defining the lives of more and more workers. When the fastest growth fields are low-wage service jobs, that’s not a victory for women, although, Poo notes, it is an opportunity to reshape the way we value service work, to make it less precarious and to create real protections for the workers who do it. In other words, not just to pay lip service to “the end of men,” but to place real value on women’s work.

It is, of course, the argument of the Right that women freely choose lower-paid work because they prefer caring professions or more free time to spend with their children. “[T]here’s no reason to think that women will ever, on average, have the same preferences as men about combining employment and parenthood, or that they will want to become librarians and truck drivers at the same rate as men,” wrote Bloomberg columnist Ramesh Ponnuru, explaining that we shouldn’t “want” the pay gap to go away. But when a job has been positioned for decades as one of the only acceptable professions for a woman (by women as well as men), is it any surprise that women “choose” it? And when the workers in those professions band together to fight for respect, their fights are seen by too many pundits as outside of feminism’s realm of concern or influence.

Chicago’s teachers, for example, went out on strike in September. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) is 87 percent female. It is led by Karen Lewis, a reformer who was the only African American woman in her class at Dartmouth. Prominent liberal male writers promptly sided with Democratic mayor Rahm Emanuel in his battle with the union, echoing anti-union rhetoric about overpaid public employees that differed from that spouted by Wisconsin governor Scott Walker only in degree, not in kind. Nicholas Kristof, in the pages of the New York Times, used “the students” as an excuse for calling the striking teachers’ demands (which he failed to list correctly) “unconscionable,” and calling for them to have fewer job protections. Dana Goldstein, a feminist and education writer, wrote one of the few pieces (on her personal blog) pointing out the feminist history of teachers’ unions, explaining that the decision to hire women as teachers was made, as the nation moved to providing public schools, because women were cheaper—and politicians and public intellectuals concealed that reasoning by portraying women as natural carers, morally superior angels.

As the teachers walked the picket lines, this profession dominated by women was demonized (and continues to be, with the anti-teachers-union movie Won’t Back Down in theaters as I write). Both major political parties supported wage cuts and “accountability” in the form of standardized testing and less job security. There was no public outcry as there was when, for example, Susan G. Komen for the Cure™ yanked its funding from Planned Parenthood. This, despite the fact that some 81 percent of elementary and middle-school teachers are women. Gloria Steinem did send a glowing endorsement of the strike, identifying herself as a co-founder of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, but prominent feminist blogs gave little or no space to the strike specifics.

On September 30, California governor Jerry Brown vetoed a historic bill, the second in the country after New York, that would have given domestic workers labor protections similar to those enjoyed by most other workers. Domestic work has long been a site of feminist analysis as well as organizing, yet even in 2012, the year of the “war on women” as Democratic politicians reminded us in fundraising emails, a Democratic governor felt safe vetoing protections for mostly-women workers. “What will be the economic and human impact on the disabled or elderly person and their family of requiring overtime, rest and meal periods for attendants who provide 24 hour care?” Brown’s statement asked, after he lauded their “noble endeavor.” “What would be the additional costs and what is the financial capacity of those taking care of loved ones in the last years of life?”

Domestic workers, Brown seemed to say, are less important than the people they care for. Feminists know that story all too well.

There’s much history to the fight over domestic work. During the sixties and seventies, the Wages for Housework movement became a site where women collectively demanded acknowledgment of their work. Selma James argued, “To the degree that we organize a struggle for wages for the work we do in the home, we demand that work in the home be considered as work which, like all work in capitalist society, is forced work, which we do not for love but because, like every other worker, we and our children would starve if we stopped.”

The women of the Wages for Housework movement were explicit that they wanted wages in part as a strategy to refuse the work. To demand a wage, they argued, was to reject that work as some natural component of female life. The National Domestic Workers Alliance isn’t out to end domestic work, but by calling for fair standards and better wages, its members are saying that the work they do is as valuable as any other kind of work, and that it is not the “natural” place of women, mainly women of color and immigrant women, to clean up after others.

While women like James were fighting for the recognition of housework as work, the mainstream feminist movement was fighting to leave it behind in favor of “career.” As Barbara Ehrenreich pointed out in Global Woman, second wave heroine Betty Friedan “raged against a society that consigned its educated women to what she saw as essentially janitorial chores, beneath ‘the abilities of women of average or normal intelligence’ and, according to unidentified studies she cited, ‘peculiarly suited to the capacities of feeble-minded girls.’”

One of the fundamental tenets of the labor movement has always been that all work is worthy of respect; that there are no degrading jobs, only degrading conditions. It was not, Ehrenreich noted, that housework was manual labor, as Friedan argued, that made it degrading, but rather, “because it was embedded in degrading relationships and inevitably served to reinforce them. To make a mess that another person will have to deal with—the dropped socks, the toothpaste sprayed on the bathroom mirror, the dirty dishes left from a late-night snack—is to exert domination in one of its more silent and intimate forms.” (Though Ehrenreich argued in this piece that people should do their own domestic work, she has been one of the NDWA’s more prominent feminist supporters.)

The National Organization for Women, Ehrenreich wrote, pushed for the Fair Labor Standards Act to include household workers, but in a way that seemed to assume paid household work was necessary so that other women could do more fulfilling work. In a way, it seems, they argued for the right to drop those socks, leave those dishes, and though they wanted the women who would do the cleaning to receive labor protections, they still seemed to see it as work that, in a way, they were too good for.

Ehrenreich suggested that part of the reason that the fight over housework remains unfinished is that the people who would keep the issue alive are largely a well-off professional class, writers and pundits and politicians and professors who are part of an opinion-making elite that has largely, “like busy professional women fleeing the house in the morning,” allowed the work to slide out of view.

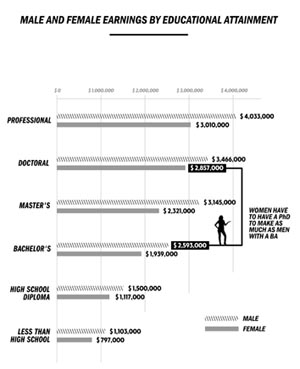

It is class that created and maintains the schism between the professional feminists and the women who look to unions rather than to feminism to help them at work. You can’t find a self-proclaimed feminist who doesn’t pay at least lip service to the idea of equal pay for equal work, but we don’t see a whole lot of connection between that problem and the actions that might be taken to rectify it. The Paycheck Fairness Act, which would allow workers to discuss salaries with one another in order to discover discrepancies, has been touted as a partial solution to the gender wage gap, but the idea, for instance, that workers should organize into a union whereby they’d bargain collectively for better pay and conditions seems lost.

By focusing solely on equal pay for equal work, we focus on the pay rates of individual women compared to individual men; we presume that work is taking place in the kind of white-collar workplace where one’s salary can be negotiated individually rather than collectively. Marilyn Sneiderman, a lifelong labor organizer and head of Avodah, the Jewish Service Corps, notes that it’s an individual struggle for a lawyer trying to make partner, but for a waitress, a janitor, a hotel housekeeper, the hope for a better job isn’t promotion through the ranks. Rather, it’s in pushing for paid sick days, for job security, for a raise—and those are things you get through organizing with your fellow workers.

As long as there has been a labor movement, there have been women in it; from rabblerousing organizers such as Mary Harris “Mother” Jones to anarchists such as Lucy Parsons and Emma Goldman. Poo points out that the first recorded domestic workers’ strike in this country was in 1881. And those women had to fight for their place within the movement. Daniel Katz, dean of the National Labor College, noted that in New York City’s famous garment workers strike in 1909, when twenty thousand women took to the streets to protest conditions in the factories where they worked, they weren’t just fighting their bosses. “The women rose up against the garment shops, but this was a rising against the men. They were demanding equal participation in the union.”

At the same time as the garment workers, a largely immigrant workforce, were fighting for their rights, the women’s suffrage movement was in full swing. The suffragists were largely middle-class, a group connected to the larger progressive movement of the same time period, trying to “uplift” the poor; Katz noted that they saw it as “a two-pronged fight, one against the powerful and one against the ‘culture’ of the poor.” The poor were to be saved, in other words, not to be asked for their opinion.

While the garment workers were on the picket lines, the men from the unions largely left them alone, but they were joined by some of the suffragists—including well-known and well-off women such as Nancy Astor and Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, women who, Katz pointed out, came from much more money than the factory owners, who were often immigrants themselves. But through the years the working women were hesitant to let the middle-class and wealthy women dictate the terms of trade union organizing.

Dorothy Sue Cobble, whose book The Other Women’s Movement looks at the “labor feminists” whose work between the suffrage era and the second wave did much for women in the workplace, argued that you cannot understand the battles between “equal rights” feminists and the type of social feminists whose organizing was done through the labor movement without looking at class.

Today’s feminist movement is not much different. The famous faces are largely white and well-educated; they are authors of books and columns and executive directors of single-focus organizations.

Yet today’s feminist leaders know better, or they should. Cecile Richards, head of Planned Parenthood, got her start as an organizer with Justice for Janitors, the revolutionary labor campaign of the 1990s to make management and the world recognize the dignity and humanity of workers doing cleaning, not just in the home, but on an industrial level. Most of the janitors were women, mostly women of color, many of them immigrants.

But the divide persists. When the National Football League locked out its referees’ union this year, it seemed to delight in exploiting the perceived “women vs. labor” split, putting a woman on the field for the first time as one of the replacement refs. Feminists cheered, labor folks groaned, and those of us who are both buried our heads in our hands, angered by the cynical move, wanting to cheer new ground broken for women but having learned the hard lesson that not all first steps by women are progressive. Whether it’s City Council speaker Christine Quinn in New York City blocking paid sick days or Marissa Mayer taking the helm at Yahoo or Shannon Eastin taking the job of a locked-out worker for less money, we have to recognize that some first steps are taken on the backs of workers, many of whom are also women.

As long as feminists are lauding the ascension of women to boardrooms for equality’s sake and not questioning what happens in those boardrooms, true liberation is a long way off.

And so we are at this point, where all too many feminists see “saving” sex workers as an appropriately feminist activity but not walking a picket line with striking teachers or nurses or hotel housekeepers. When Dominique Strauss-Kahn was accused of raping Nafissatou Diallo, a hotel housekeeper, feminists rallied to her defense, but that support hasn’t led to increased support for hotel worker unions even as Hyatt hotel workers engage in a nationwide boycott, even though UNITE HERE, the hotel workers’ union, supported Diallo and protects workers like her from being fired for speaking out against abuse. Instead, it led to too many swoons over Christine Lagarde, who took Strauss-Kahn’s place at the International Monetary Fund.

As long as feminists are lauding the ascension of women to boardrooms for equality’s sake and not questioning what happens in those boardrooms, true liberation is a long way off.

This past July, a group of women activists, community leaders, organizers, retail and restaurant workers, and reporters gathered on the front steps of New York’s City Hall to speak out about paid sick leave.

Not present in the heat but part of the event just the same was Gloria Steinem, feminist luminary, who that morning had come out in the pages of the New York Times in support of a paid sick leave bill—and pressuring City Council speaker Christine Quinn, an out lesbian who hopes to become New York City’s first woman mayor, to allow the bill to come up for a vote.

Quinn will no doubt count on the support of feminist heavy hitters like Steinem when it comes campaign time. But Steinem and Ai-Jen Poo, and about two hundred other influential women, had signed a letter saying that their support for her was contingent on her allowing a vote on paid sick days. As long as women remain the primary caregivers in their families and also make up the majority of the city’s low-wage workers without benefits, this is a feminist fight. It cannot be disguised with appeals to breaking the mayoral glass ceiling.

The gathering and the public campaign to press Quinn to stand up for all women, not just the wealthy ones, is an all too rare example of feminist leaders fighting for a labor movement goal. At press time, Quinn was holding firm. But the campaign for paid sick leave is a hopeful sign, a sign that perhaps feminism is reconsidering its place on the picket line. Trickle-down feminism won’t do the job.

Sarah Jaffe is the former labor editor at Alternet and has written about the economy, organizing, and social movements for the Nation, Dissent, the American Prospect, Truthout, and Jacobin,among others.

Infographics by Imp Kerr. Data from the National Women’s Law Center and the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Author’s note, January 28, 2013: “Trickle-down feminism” is a term that has been used by, among others, Tressie McMillan Cottom, Laurie Penny, and Kari Kendall Cameron.

[contentblock id=subscribe-plain]