Why Free College Is Necessary

Why Free College Is Necessary

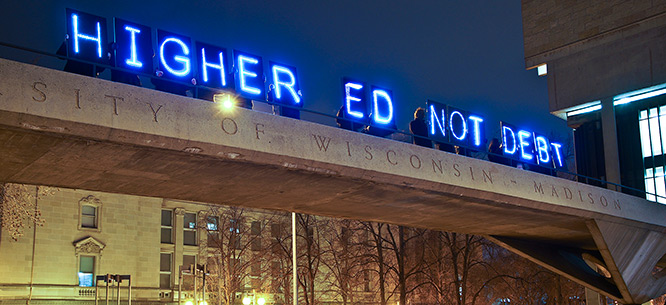

Higher education can’t solve inequality, but the debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to education discourse.

Free college is not a new idea, but, with higher education costs (and student loan debt) dominating public perception, it’s one that appeals to more and more people—including me. The national debate about free, public higher education is long overdue. But let’s get a few things out of the way.

College is the domain of the relatively privileged, and will likely stay that way for the foreseeable future, even if tuition is eliminated. As of 2012, over half of the U.S. population has “some college” or postsecondary education. That category includes everything from an auto-mechanics class at a for-profit college to a business degree from Harvard. Even with such a broadly conceived category, we are still talking about just half of all Americans.

Why aren’t more people going to college? One obvious answer would be cost, especially the cost of tuition. But the problem isn’t just that college is expensive. It is also that going to college is complicated. It takes cultural and social, not just economic, capital. It means navigating advanced courses, standardized tests, forms. It means figuring out implicit rules—rules that can change.

Eliminating tuition would probably do very little to untangle the sailor’s knot of inequalities that make it hard for most Americans to go to college. It would not address the cultural and social barriers imposed by unequal K–12 schooling, which puts a select few students on the college pathway at the expense of millions of others. Neither would it address the changing social milieu of higher education, in which the majority are now non-traditional students. (“Non-traditional” students are classified in different ways depending on who is doing the defining, but the best way to understand the category is in contrast to our assumptions of a traditional college student—young, unfettered, and continuing to college straight from high school.) How and why they go to college can depend as much on things like whether a college is within driving distance or provides one-on-one admissions counseling as it does on the price.

Given all of these factors, free college would likely benefit only an outlying group of students who are currently shut out of higher education because of cost—students with the ability and/or some cultural capital but without wealth. In other words, any conversation about college is a pretty elite one even if the word “free” is right there in the descriptor.

The discussion about free college, outside of the Democratic primary race, has also largely been limited to community colleges, with some exceptions by state. Because I am primarily interested in education as an affirmative justice mechanism, I would like all minority-serving and historically black colleges (HBCUs)—almost all of which qualify as four-year degree institutions—to be included. HBCUs disproportionately serve students facing the intersecting effects of wealth inequality, systematic K–12 disparities, and discrimination. For those reasons, any effort to use higher education as a vehicle for greater equality must include support for HBCUs, allowing them to offer accessible degrees with less (or no) debt.

The Obama administration’s free community college plan, expanded in July to include grants that would reduce tuition at HBCUs, is a step in the right direction. Yet this is only the beginning of an educational justice agenda. An educational justice policy must include institutions of higher education but cannot only include institutions of higher education. Educational justice says that schools can and do reproduce inequalities as much as they ameliorate them. Educational justice says one hundred new Universities of Phoenix is not the same as access to high-quality instruction for the maximum number of willing students. And educational justice says that jobs programs that hire for ability over “fit” must be linked to millions of new credentials, no matter what form they take or how much they cost to obtain. Without that, some free college plans could reinforce prestige divisions between different types of schools, leaving the most vulnerable students no better off in the economy than they were before.

Free college plans are also limited by the reality that not everyone wants to go to college. Some people want to work and do not want to go to college forever and ever—for good reason. While the “opportunity costs” of spending four to six years earning a degree instead of working used to be balanced out by the promise of a “good job” after college, that rationale no longer holds, especially for poor students. Free-ninety-nine will not change that.

I am clear about all of that . . . and yet I don’t care. I do not care if free college won’t solve inequality. As an isolated policy, I know that it won’t. I don’t care that it will likely only benefit the high achievers among the statistically unprivileged—those with above-average test scores, know-how, or financial means compared to their cohort. Despite these problems, today’s debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to higher education discourse—a concept that fifty years of individuation, efficiency fetishes, and a rightward drift in politics have nearly pummeled out of higher education altogether. We no longer have a way to talk about public education as a collective good because even we defenders have adopted the language of competition. President Obama justified his free community college plan on the grounds that “Every American . . . should be able to earn the skills and education necessary to compete and win in the twenty-first century economy.” Meanwhile, for-profit boosters claim that their institutions allow “greater access” to college for the public. But access to what kind of education? Those of us who believe in viable, affordable higher ed need a different kind of language. You cannot organize for what you cannot name.

Already, the debate about if college should be free has forced us all to consider what higher education is for. We’re dusting off old words like class and race and labor. We are even casting about for new words like “precariat” and “generation debt.” The Debt Collective is a prime example of this. The group of hundreds of students and graduates of (mostly) for-profit colleges are doing the hard work of forming a class-based identity around debt as opposed to work or income. The broader cultural conversation about student debt, to which free college plans are a response, sets the stage for that kind of work. The good of those conversations outweighs for me the limited democratization potential of free college.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a contributing editor at Dissent. Her book Lower Ed: How For-Profit Colleges Deepen Inequality is forthcoming from the New Press.

This article is part of Dissent’s special issue of “Arguments on the Left.” Click to read contending arguments from Matt Bruenig and Mike Konczal.