“They Did What They Liked”: Chevron and Dow on Trial

“They Did What They Liked”: Chevron and Dow on Trial

Over decades, U.S. multinationals have developed a formidable arsenal of legal tactics to escape accountability abroad.

“They want me to be bankrupt, they want my wife to leave me, they want me to jump off a building,” says Steven Donziger, a lawyer based in New York City whose team won an unprecedented judgment against Chevron in 2011. That year, an Ecuadorean court found Texaco guilty of having polluted close to 2,000 square miles of the Amazon basin with crude oil, toxic wastewater, and other contaminants. The country’s Supreme Court eventually ordered the company’s successor, Chevron, to pay $9.5 billion for environmental remediation, medical treatment, and other relief for those affected. But Donziger’s victory painted a bull’s-eye on his back. The lawyer says he’s been watched; that he’s had laptops, thousands of documents, bank statements, and tax returns seized by court order and handed to Chevron’s lawyers; and that friends and supporters have been turned against him by threats of ruinous lawsuits.

Worst of all, this March a New York federal judge convicted Donziger under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act of heading a criminal undertaking that had corrupted and intimidated Ecuadorean judges in order to shake down Chevron. (If the $9.5 billion awarded to his clients were ever collected, Donziger, who has worked on the case for most of the two decades it took to reach completion, would stand to earn millions in lawyer’s fees.) Donziger has appealed. Even if he is vindicated, however, this novel deployment of the RICO Act—normally applied to mobsters and drug syndicates—adds a particularly nasty weapon to the already formidable arsenal that U.S. multinationals have developed, with considerable help from American judges, to defeat demands for accountability by litigants in poor foreign countries.

Public interest lawyer Rob Hager points out that according to the World Justice Project, the U.S. civil justice system ranks twenty-seven out of ninety-nine countries, which is low by Western standards (Denmark claims first place and Venezuela, last). “I would say that the quality is at its lowest in class-action suits against U.S. corporations,” Hager continues in an email interview. “That is where the system is most alert to see that injustice is done, because real money is at stake.” Foreign plaintiffs in particular find it all but impossible to get a jury trial in the United States, where the grievous harm they’ve suffered is most likely to win ample damages.

Several of the strategies used by Chevron to thwart Ecuadorean plaintiffs were earlier tested by Union Carbide, now owned by Dow Chemical, in fending off financial liabilities from the 1984 gas disaster in Bhopal, India. In the three decades since possibly the worst industrial accident in history (barring Chernobyl), some 20,000 of those who inhaled poison gas have died, hundreds of thousands survive with permanent impairment to their pulmonary, nervous, genetic and reproductive systems, and toxins abandoned in and around the former factory site have inexorably leached into the city’s groundwater. Against all odds, the survivors continue to battle for justice. Reviewing the trajectories of several such efforts, a 2014 Amnesty International report, Injustice Incorporated, identified three kinds of hurdles that plaintiffs from the global South face in seeking accountability from multinationals: legal barriers in developed countries to actions brought by foreigners, access to information, and corporate influence on governments in developing countries.

The first barrier is especially high in the United States, where judges can simply dismiss a case filed by victims of a disaster that occurred on foreign soil, on the grounds that the forum is inappropriate. Such a fate befell both the Ecuador and Bhopal plaintiffs, forcing them to instead pursue their respective cases in their home countries—which have far less experience in undertaking such massive litigation and limited ability to compel compliance from multinationals domiciled in the United States. The second obstacle, access to information, applies to elusive scientific data (such as the quantities and medical effects of oil spilled in the Amazon) as well as to decision-making structures within the corporation in question. Although essential to establishing liability by the parent company (given that the foreign subsidiary rarely has the resources to remedy the harm done) the relevant information can be very difficult for overseas litigants to obtain. Access to information can therefore pose an insurmountable problem.

A third hurdle, best illustrated by the Bhopal case, is the immense leverage that wealthy and well-connected corporations often exert over governments in developing countries. And when such influence falters, as it did in Ecuador, Chevron’s trail-blazing litigation against plaintiffs’ lawyers demonstrates how U.S. courts can again rescue corporations. All in all, the story of local and national groups’ efforts to hold Dow and Chevron accountable illustrate virtually all the techniques U.S. multinationals have thus far employed to protect their bottom lines from impoverished plaintiffs from developing countries—whether they are amenable to American pressure (India) or not (Ecuador).

On the night of December 2, 1984, forty tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC), a substance more lethal than phosgene (used as a poison gas in the First World War), and other unknown gases burst out of a storage tank in a pesticide factory owned by the Union Carbide Corporation in Bhopal, India. The shimmering MIC fog, heavier than air, descended on fifteen square miles of the densely populated city, smothering the slums near the factory. People woke up coughing, choking, and blinded, and ran for air only to collapse on the streets. Days later, reporters found cranes removing corpses by the truckload, hordes of children with red teary eyes searching for family members, and gas victims still streaming into the local hospital.

MIC is so lethal that few scientists had dared to test its properties—even a whiff escaping from a test tube can kill. There is no known antidote. In the first hours after the accident, company officials told doctors that the gas was not dangerous; when that story collapsed, they claimed that survivors would not have permanent injuries. Studies using animals have since established that MIC is absorbed into the blood stream and delivered to every organ in the body, damaging several of them permanently. Thousands of fetuses in the affected area have since died in the womb, and, according to Satinath Sarangi of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, thousands of deformed babies have also been born.

Union Carbide’s medical director initially advised treatment with sodium thiosulphate, an antidote for cyanide poisoning. Within days, however, the company reversed its stance, insisting that victims of the accident were not suffering from cyanide toxicity, and Bhopal’s director of medical health ordered a halt to administration of the antidote. When volunteer doctors in a makeshift clinic continued to use it, the police invaded their clinic, arrested forty people (including six doctors), beat them up, and confiscated their documentation. Sodium thiosulphate was known to be useful in measuring the extent of cyanide poisoning, which, unlike the hitherto unknown MIC, had a history of garnering heavy damages from U.S. courts. Sarangi and others suspect that someone high up in the local administration was protecting Union Carbide’s bottom line by depriving patients of the only antidote that was helping them. Partly because of such manipulations, and partly because of the intransigent nature of MIC itself, “[no] effective treatment protocol was ever put in place for Bhopal survivors,” notes the Amnesty report. According to studies by the Centre for Rehabilitation Studies in Bhopal, in 2000 those exposed to the gas were still dying at the rate of at least one a day.

Controlling the evidence is key to mounting a successful defense, and in a complex case involving many victims, unknown health effects, and a complicit government, this can be all too easy. Union Carbide subsequently claimed that only 1,408 had died—those whose corpses had been registered in the morgue of the Hamidia Hospital in Bhopal—although the sale of shrouds (for the burial of Muslims) and of firewood (for the funeral pyres of Hindus) indicated that more than 7,000 had perished in the first week. A senior UNICEF official put that initial toll at 10,000.

Among the first Americans to arrive in Bhopal were contingency lawyers, almost universally described as “ambulance chasers,” who quickly signed up thousands of victims and filed cases in thirteen different U.S. states. In February 1985 a committee of what Hager describes as “handpicked” federal judges comprising the Multi-District Litigation Panel consolidated these actions and assigned them to Judge Keenan in the Southern District of New York. That assignment, says Hager, was the first sign that the U.S. justice system was moving to protect Union Carbide: Keenan was a Reagan appointee with virtually no experience in civil litigation, who had also professed a dislike of massive and complex cases. He was unlikely to hear the case on its merits.

Hager, who represented U.S. public interest and church groups in the proceedings, was dismayed to find Keenan following a strategy developed months earlier in the Agent Orange case brought by Vietnam veterans: the “collusive class action settlement,” as Hager termed it in a 1995 article in the journal Covert Action. Keenan appointed three lawyers to represent the Bhopal victims, among them one Stanley Chesley, who had just negotiated a cheap settlement for Agent Orange victims despite their vociferous opposition. Hager estimated that by U.S. standards, the damages in Bhopal amounted to $35 billion (not counting punitive damages). Even adjusting for cheaper standards of living in India would still lead to an award of more than $5 billion. Instead, Keenan and his chosen lawyers negotiated a settlement of $350 million.

|

Meanwhile, the Indian government had assumed by an act of parliament the “exclusive right” to represent the Bhopal victims—which, it would turn out, would rob the survivors of the right to pursue Union Carbide on their own. Because the settlement caused outrage in India, the government was compelled to reject it. Subsequently, Union Carbide pleaded in Keenan’s court that the case should be heard in India (where damages awarded according to Indian precedents would presumably be far less than in U.S. courts). The forum non conveniens doctrine, a relic of English law that until 1929 was considered unconstitutional in the United States (it is barred in the European Union), argues that in certain circumstances, class-action lawsuits involving incidents in foreign countries are best heard in those countries. Hager acidly observes in his article that the doctrine, which has been invoked in almost all such cases, relieves U.S. corporations from the “inconvenience” of liability for their foreign actions. Indian courts had no experience with such complex litigation, but in May 1986 Keenan used forum non conveniens to dispatch the Bhopal case to India. Hager appealed this decision all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case.

Geopolitics had meanwhile come into play. Newly elected Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was eager to tilt India away from its former “non-aligned” stance in relation to the Cold War powers, toward a closer relationship with the United States. Union Carbide, for its part, had intimate ties with the U.S. State Department dating back to the Second World War, when it started enriching uranium for atom bombs. According to Ward Morehouse, who founded the International Coalition for Justice in Bhopal and remained a tireless advocate for the gas survivors until he died in 2012 (I interviewed him in 1995), Gandhi visited the United States twice in 1985 with a “shopping list.” The State Department was believed to have placed Bhopal on its own list of issues for discussion. In the Covert Action article, Hager observed that at this time the United States decided to allow India to import previously prohibited military technology, following which the Indian government dropped its opposition to the Keenan decision. “Although there is no hard evidence linking the sudden thaw in India-U.S. relations to UCC’s generous treatment in the Bhopal case, the coincidence is worthy of note,” he wrote.

The case resumed in the Bhopal district court in January 1988. Whereas in New York Union Carbide had praised the sagacity of Indian justices, in India it challenged the court at every step. “It was a war of attrition,” recalls Upendra Baxi, a legal scholar who now teaches at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom. When the Bhopal court ordered Union Carbide to pay $270 million in interim compensation in order to bring desperately needed relief—without prejudicing the outcome of the case—the company appealed to the state high court. That court upheld the ruling, whereupon Union Carbide went to the Indian Supreme Court.

For a long time organizations representing gas victims could not find a lawyer to represent them, recalls Baxi, because Union Carbide had “suborned virtually all Supreme Court lawyers by giving them a retainer fee.” Once proceedings began, Union Carbide stalled them by invoking the “corporate veil,” another standard defense against accountability. The company argued that it had no control of foreign operations and therefore that its Indian subsidiary bore all the blame. In truth, key features of the factory that made the catastrophe inevitable, such as the vast tanks in which the highly poisonous, reactive, and unstable MIC was stored, had been designed in the United States (a former senior executive of Union Carbide, Edward Munoz, attested that he had warned against the storage of MIC in such extraordinary quantities, but had been overruled and subsequently fired). Nonetheless, lacking information that clarified Union Carbide’s internal structures of responsibility, the plaintiff’s lawyers struggled to pierce the corporate veil.

They need not have bothered: Union Carbide was basically buying time until it could negotiate a deal. In 1987 Gandhi visited the United States for the third time. A country studies report in the U.S. Library of Congress notes that as relations between the two countries warmed, Washington increasingly supported India’s foreign policy initiatives. India, for its part, started to liberalize its economy, and U.S. investment began pouring in, amounting to $1 billion in 1989. In February that year, India’s Supreme Court announced a settlement of $470 million with Union Carbide and precluded all further litigation, either civil or criminal, relating to the disaster.

Union Carbide’s shares jumped by $2 the very next day: the company had finally achieved the collusive class-action settlement it had long sought. Activists tend to blame the chief justice of the Indian Supreme Court, Raghunandan S. Pathak, for the sell-out: within months he was appointed to the International Court of Justice, a position he could likely have achieved only with U.S. support. However, Baxi and Hager believe that Rajiv Gandhi personally negotiated the settlement amount. According to Kamal Mitra Chenoy, a professor of politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, the text of the settlement was written by an Indian law firm representing Union Carbide and vetted by American lawyers who had flown into New Delhi for that purpose. “India is not supposed to be a tin-pot dictatorship or a banana republic,” said Chenoy in a telephone interview. “Still, these things happened.”

Rajiv Gandhi effectively sacrificed the Bhopal survivors in order to signal that India was open for business, no matter the cost to ordinary people.

Rajiv Gandhi effectively sacrificed the Bhopal survivors in order to signal that India was open for business, no matter the cost to ordinary people. The settlement was insufficient to provide life-long medical care (conservatively estimated at $600 million) for the more than half million Bhopalis who had filed injury claims, let alone to compensate those who had lost relatives. (Union Carbide did contribute $20 million from the sale of its Indian subsidiary to the construction of a dedicated hospital in Bhopal.) Subsequently—and mysteriously—the Indian Council of Medical Research, the country’s premier medical institute, halted its epidemiological studies in Bhopal. According to Sarangi, publication of the results was delayed until 2004 because they indicated that the numbers of injuries and deaths were far higher than what was accounted for in the settlement.

The maximum that Union Carbide was willing to pay, Hager explains in his article, was determined by what its directors could raise without eroding the company’s share values, which would have invited shareholder lawsuits that threatened the directors’ personal assets. Moreover, by the end of 1986, Union Carbide had sold off several divisions and prepaid its debts, reducing its equity from $5 billion to $1 billion. As a result, the most that Bhopal victims could have recovered in any case was $1 billion. (This tactic has since been emulated by Dow Corning, which pleaded bankruptcy in 1995 to avoid financial responsibility in a silicone breast implant case, notes Hager. More recently, BP has been accused of transferring money “off the company’s books and into investors’ pockets” to avoid paying up for the Gulf spill.) Wil Lepkowski, a correspondent for Chemical and Engineering News who has followed the Bhopal disaster from the start, wrote that a single Union Carbide share “worth $35 in December 1984 would … have accumulated a worth of $700 in December 1994 on the assumption that shareholders reinvested all dividends and distribution rights.” That observation belies the common argument that shareholders have a financial motivation to ensure that companies they invest in do no harm.

What is more, had Union Carbide received a judgment it did not like, it could have gone back to New York and challenged it on the grounds that the Indian Supreme Court had not followed U.S. standards of due process. If that happened, says Baxi, “the judgment of the highest court in India could have been thrown out by the lowest court in the United States,” a prospective insult that may also have persuaded Pathak to accept the settlement. At the time, Baxi argued that this outcome was unlikely. But it’s exactly what transpired when, more than a decade later, Chevron received a judgment it did not like from an Ecuadorean court it had earlier insisted was fair and just.

“If you walk around in the Lago Agrio region, you see lots of kids with deformities—without fingers, without ears,” says Manuela Picq, professor of international relations at the Universidad San Francisco in Quito. “I asked a mother about it, and she said, ‘Our kids are just born like that.’ ” The ramshackle town of Lago Agrio in the Oriente (the Amazon basin of Ecuador) sprang up in 1964 when a consortium comprising Texaco and Gulf began exploring for oil in the jungle around it. The Ecuadorean government wanted to colonize the Amazon and to learn how to produce oil on its own. So the company built roads into the forest, enabling colonists to fight back the indigenous peoples and settle in. Three years in, it struck a gusher. After production began in the early 1970s, Petroecuador, the national company, joined in and assumed Gulf’s share. As mentor and guide, Texaco retained technological and operational control.

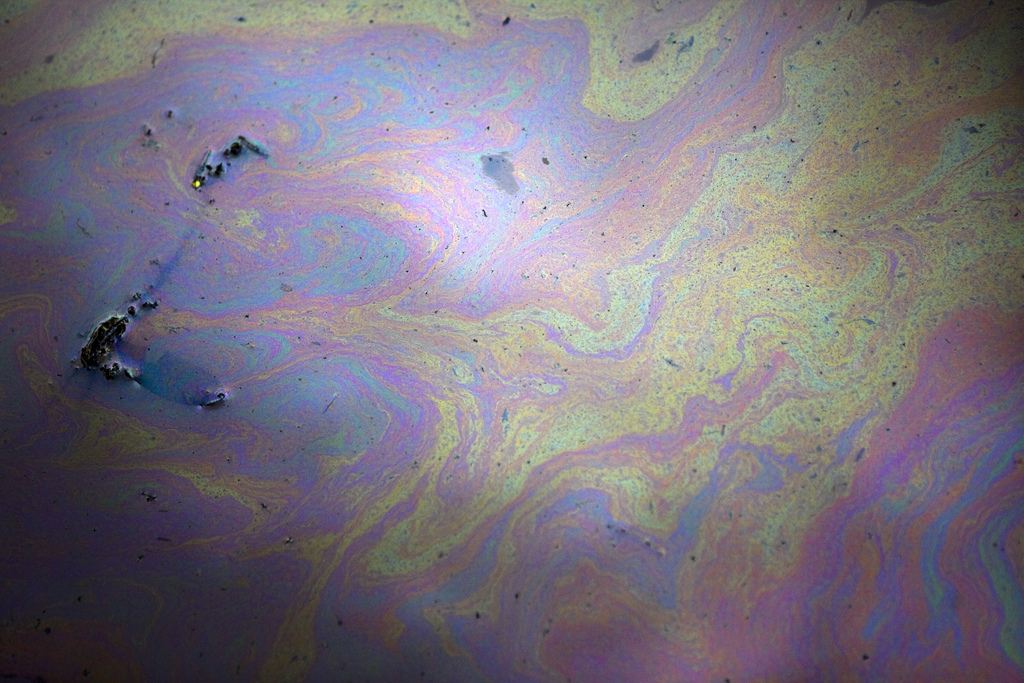

At the time, Ecuador had few environmental regulations and little interest in enforcing them. “The government gave Texaco the military to back them up,” says an American anthropologist who asked not to be named. “They did what they liked.” The company constructed a network of pipelines across the Amazon—cutting costs by letting spilled crude lie where it fell—and left pits full of toxic sludge across the Oriente. And whereas in the United States it injected contaminated water produced in the drilling process deep underground, in Ecuador the company simply drained waste into ponds or local waterways from which forest dwellers drank. Fish died, and locals contracted cancers and other ailments they’d never encountered before.

As indigenous Indians retreated from the contaminated regions, they clashed with tribes deeper in the Amazon; many others were assimilated into Lago Agrio’s impoverished workforce or forcibly relocated in a process that Judith Kimerling, professor of environmental policy at Queens College in New York, describes in a paper as “a systematic, ethnocidal public policy and campaign, promoted and aided by Ecuador and Texaco.” By 1992, when Texaco’s contract expired and Petroecuador inherited the operations, the consortium had extracted nearly 1.5 billion barrels of Amazon crude, while discharging 3.2 million gallons of toxic wastewater every day and spilling twice as much oil as in the Exxon-Valdez disaster from the operation’s main pipeline, to say nothing of others that branched through the rainforest.

|

The next year a U.S.-based Ecuadorean, Cristobal Bonifaz, filed a class-action lawsuit in a New York federal district court on behalf of 30,000 Amazon residents who called themselves the afectados—those affected by oil. The plaintiffs demanded a cleanup of the contamination as well as remedial measures such as piped water. Even as the case wound its way through the courts, slowed down by tussles over the corporate veil and forum non conveniens, Texaco agreed in 1995 with the Ecuadorean government to remediate 37.5 percent of the contamination, corresponding to its share of the consortium. After spending $40 million on what Kimerling describes as a “largely cosmetic” cleansing (nonetheless certified by experts retained by Texaco), the company received a full discharge of claims from the Ecuadorean government. Crucially—and unlike the Bhopal settlement—this agreement did not bear the approval of the Supreme Court, and therefore did not preclude individuals from pursuing the company on their own. Even so, Ecuador filed a brief in New York in favor of Chevron, arguing that the plaintiffs had no right to sue.

Asked why the two parties had never settled, Donziger, who had joined the case at a later stage, explained that there “just wasn’t a settlement on the table that was meaningful.” Nonetheless, the afectados suffered the same forum non conveniens rebuff as the Bhopalis. In 2001, the same year that Chevron acquired Texaco, Judge Jed Rakoff of the federal district court in New York City brushed aside a U.S. State Department report alleging “shortcomings in the politicized, inefficient, and corrupt legal and judicial system” in Ecuador and dismissed the case. The power of U.S. courts “does not include a general writ to right the world’s wrongs,” Rakoff explained. An appeals court upheld the decision on the condition that Chevron submit to the jurisdiction of Ecuadorean courts.

In 2003 the case resumed in Lago Agrio, this time naming forty-eight plaintiffs from both the colonist and indigenous communities. They demanded that the court determine the cost of environmental remediation and order Chevron to pay this amount to the Amazon Defense Front or Frente, a local nongovernmental association that would administer the cleanup. Kimerling charges that the Frente is controlled by colonists and does not enjoy the confidence of the Huaorani, one of the indigenous groups it claims to represent. Be that as it may, the plaintiffs were so fearful that Chevron would use its deep pockets to influence the court proceedings that Donziger, who managed the legal team, embarked on an aggressive public relations campaign. Apart from inviting Hollywood stars to tour the Oriente, he solicited filmmaker Joe Berlinger to make a documentary on the ongoing case and helped obtain financing for the venture. This decision would ultimately backfire.

Meanwhile, the Lago Agrio court embarked upon an ambitious program of judicial inspections of contaminated sites, in the presence of lawyers from each side, in order to determine the extent of Chevron’s culpability. Quantifying the vast wastewater and oil spills in the Oriente and determining what fraction of these stemmed from Texaco’s operations posed a close-to-insurmountable challenge. And as the site visits dragged on, Ecuador underwent a political upheaval: a socialist, Rafael Correa, was elected president in late 2006. Invited by Donziger to tour waste pits, Correa described the contamination as a “crime against humanity.” Suddenly, the odds were stacked against Chevron.

Later that year, because the judicial inspections were taking so long, the court also acceded to the plaintiffs’ demand and instead appointed an independent expert, Richard Cabrera Vega, to estimate the cost of remediation. At about this time, Chevron changed its strategy. Whereas in Judge Rakoff’s court the company had praised Ecuadorean courts, it now sought to demonstrate that they were corrupt. In 2009 the company produced a video that allegedly showed the presiding judge, Juan Núñez, accepting a bribe. The New York Times reviewed the video, however, and found that it did nothing of the sort. Núñez protested his innocence and recused himself from the case.

That same year Berlinger released his documentary, Crude, much of which showed Donziger in private consultation with his legal team. In a scene edited out of the final cut, one of Chevron’s lawyers, Randy Mastro of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher in New York, found evidence that a physician distantly associated with Cabrera had met with members of Donziger’s team. Mastro, a former federal prosecutor who had successfully taken on New York crime bosses and was in the process of demolishing claims by Nicaraguan plantation workers against Dole, now unveiled a sharp new weapon: an obscure statute that enables an American litigant facing a foreign lawsuit to obtain information that can aid its case. Chevron went on to file dozens of “discovery” lawsuits in jurisdictions across the United States, demanding documents from lawyers who were aiding the plaintiffs and unedited footage from Berlinger.

“They were basically able to audition a lot of judges,” says lawyer Aaron Marr Page, who assists Donziger. New York federal judge Lewis Kaplan stepped to the fore, ordering Berlinger to turn over all his six hundred hours of footage. Berlinger, backed by media companies, pleaded the First Amendment, but the court of appeals ruled against him on the grounds that he had not acted as an independent journalist. The clips revealed Donziger at his brashest: making disparaging remarks about Ecuadorean judges and joking that given the changed political climate, any judge who ruled against the afectados would fear being bumped off. Kaplan subsequently forced Donziger to hand over all his laptops and papers, including his emails and private diary, to Chevron’s investigators. (Using a procedure for marking cases as related, Kaplan has since heard all cases brought against Donziger in the Southern District of New York.)

Never before had a company had such extraordinary access to its legal adversary’s private and confidential documents.

Never before had a company had such extraordinary access to its legal adversary’s private and confidential documents. Among other things, these indicated what Chevron claimed to be improper remittances sent to Cabrera by Donziger’s team. Donziger explains that under Ecuadorean law, the party that requests the services of an expert is required to pay him or her, and that “all payments to Cabrera were entirely appropriate at all times, consistent with Ecuador law and custom.” He adds that Chevron could have cooperated with Cabrera as well but chose not to. In February 2011, even before Ecuadorian judge Nicolás Zambrano had announced his historic verdict against Chevron, Judge Kaplan had blocked its enforcement.

In his judgment, Zambrano declared that in view of the controversy, he had cast aside the Cabrera report and relied instead on the earlier inspections to determine the remediation cost. He assessed the fine at about $9 billion, to be doubled to $18 billion unless Chevron apologized, which it did not. The case went on to Ecuador’s Supreme Court, which upheld the judgment in 2013 while reducing the fine to $9.5 billion. Because Chevron had few assets remaining in Ecuador, the afectados began proceedings to collect in Canada, Argentina, and Brazil, where the company does have substantial holdings.

The RICO trial against Donziger and his associates followed. The lawyer alleges that Chevron dropped a $60 billion claim against him because that would have brought forth a jury trial, while the company wanted Kaplan alone to rule. “[T]he evidence at trial established that Donziger, a New York lawyer and resident, here formulated and conducted a scheme to victimize a U.S. company through a pattern of racketeering,” stated Kaplan in his judgment.

The judge “bristled with hostility toward Donziger,” asserts Page. “He accused him of trying to influence the balance of payments between Ecuador and the U.S.” In fact, Chevron had lobbied the U.S. trade representative for years to revoke export preferences enjoyed by Ecuador under a 1991 Andean treaty unless the country halted the trial. (That plea went nowhere, possibly because Donziger was not without connections himself: Obama was a classmate at Harvard Law School. As a senator, Obama had signed on to a letter urging the trade representative to reject Chevron’s efforts because the afectados “deserve their day in court.”) Last year Ecuador withdrew from the pact in any case, because of its dispute with the United States over the asylum offer Ecuador made to Edward Snowden.

Kaplan’s bias is evident in the very different ways in which he viewed Donziger’s payments to Cabrera and Chevron’s payments to Alberto Guerra, a former Ecuadorean judge (who had been dismissed for corruption) and the company’s chief witness. Guerra claimed in the RICO trial to have promised Judge Zambrano a bribe, on Donziger’s behalf, if he allowed the plaintiffs to write the judgment. Whereas Kaplan found proof of a criminal conspiracy in Donziger’s actions, when it came to Chevron moving Guerra and his family to the United States and providing them with living and other expenses, he saw evidence of a “private witness protection program.” Nor did Kaplan allow Donziger’s counterclaim, alleging that Chevron had sought to bribe a judge and had made “exorbitant” payments to witnesses testifying on the company’s behalf, to go forward. (Under U.S. law, expert witnesses—those who offer an informed opinion—may be paid, but fact witnesses—those who testify to the facts of a case—may not.) Donziger further charges that Kaplan owns Chevron shares; the company did not respond to requests for comment.

“I’m the principal target of sixty law firms, two thousand lawyers, and ten surveillance companies,” says Donziger, who remains defiant. “Everyone in America thinks we’re losing. We’re not, we’re winning. It’s probably going to be overturned on appeal.” Moreover, he adds, if the afectados cannot collect in the United States, it makes it more likely that they will get a sympathetic hearing in other countries. Chevron has meanwhile obtained an injunction from a trade arbitration panel in the Hague ordering Ecuador to stop trying to enforce the verdict. But Ecuador has refused to obey, asserting that human rights override trade relations.

Kaplan’s role in the RICO judgment finds a reflection in Judge Keenan’s ongoing role in the Bhopal gas case, which activists have sought to resurrect in the United States. The judge has dismissed every action having to do with Bhopal, including a plea that Union Carbide remediate the contaminated site. In 2010 Keenan even heard and dismissed a plea to transfer a case from his court, on the grounds that disparaging remarks he had earlier made about the Bhopal plaintiffs were irrelevant, and that for anyone else to study the case would be a waste of judicial resources. “He’s retired,” says Page, who also advises Bhopal survivors. “But he emerges from retirement to hear the Bhopal case. It’s the only one he still hears. He never lets us get near the merits of the case.”

The survivors have had more luck in India, where the Supreme Court reinstated the criminal cases against Union Carbide officials in 1991. Nineteen years later, in 2010, the Bhopal district court convicted seven Indian employees of the company of criminal negligence and sentenced each of them to fines and two years in prison, although they were immediately released on bail. Under pressure from activists, the Indian government had already asked the United States to extradite Warren Anderson, who was CEO at the time of the disaster. (To no one’s surprise, that hasn’t happened.) Far more significant, activists used India’s Right to Information Act to obtain documents confirming Rajiv Gandhi’s collusion in the mishandling of the Bhopal case. Facing fierce attacks in the media, in 2010 the government submitted a “curative petition” to the Supreme Court asking that the settlement of 1989 be reopened.

An innovation dating from 2002, a curative petition allows the Supreme Court to review one of its own judgments if it is argued that it led to a gross miscarriage of justice. The court agreed to hear the petition against Dow (which bought Union Carbide in 2001) but to date has not scheduled a hearing, a delay that observers believe is significant. Moreover, the revised figure for deaths (5,295) that the Indian government submitted in the petition is puzzlingly low, given that projections based on the truncated epidemiological studies point to 20,000 or more. And the government is demanding additional compensation of up to $1.2 billion, whereas according to survivors’ organizations such as the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, it should be at least $8.1 billion.*

|

The Bhopal advocates’ ability to keep the flame burning has nonetheless brought them some unwelcome attention. In 2011 hacktivist Jeremy Hammond revealed via WikiLeaks the emails of a private intelligence agency, Stratfor—an offence for which he is serving a ten-year sentence. Among Stratfor’s targets were American, British, and Indian advocates for Bhopal victims. The list included the Yes Men, inspired pranksters who spoofed Dow on BBC and have also targeted Chevron with fake ads. In addition, Dow has hit Indian activists with lawsuits seeking hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages for activities such as throwing balloons filled with blood at the façade of Dow’s headquarters in Mumbai. (“We basically said, ‘You have the blood of Bhopal people on your hands,'” explains Sarangi, who participated in the protest.)

Moreover, Dow has lobbied the Indian government to release it from demands to clean up the factory site. Diplomatic cables released by Chelsea Manning via WikiLeaks show that in 2007 the U.S. Ambassador to India, David C. Mulford, also spoke for Dow in asking the government to drop the remediation demand. A senior Indian official, Montek Singh Ahluwahlia, explained that he “did not believe Dow was responsible for the cleanup” but that it was difficult to drop the claims because Bhopal protesters were “very active and vocal.” (Dow India did not reply to queries from this author.)

Despite its deep connections and its dubious practices (in 2007 Dow paid the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission a $325,000 fine for bribery in India), all is not well for the company’s expansion plans in the country. The company had fired employees at its West Virginia research-and-development center in anticipation of the construction of a new global hub near Pune, India. But in 2008 protesters set fire to the Indian building, which apparently was on sacred ground. Although the dispute was local, the toxic legacy of Bhopal undoubtedly contributed to the fear and suspicion with which villagers viewed the Dow center. And other companies have suffered as well: despite persistent U.S. pressure, the former Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh, failed to push through parliament a law that would fully indemnify foreign nuclear suppliers, including GE and Westinghouse, from liability in case of an accident. At the time, the Bhopal disaster was in the news and undoubtedly influenced lawmakers.

Despite decades of intense effort, however, neither those stricken by gas in Bhopal nor those affected by oil in Ecuador have received the relief or justice they deserve. In large part, that is because they were denied their day in U.S. courts. “When victims of U.S. corporations come to the U.S. for justice, they are doing so because they have a pretty good reason to doubt the capacity of their country to handle the case,” observes Marco Simons, legal director of EarthRights International. U.S. courts have considerable experience in handling large environmental cases and usually deliver a fair and predictable outcome. For that very reason, multinationals seek to avoid a trial here. “Quite often the motivation for dismissing the case on the basis of forum non conveniens,” Simons explains, “is that the corporation is convinced it has enough power to influence the outcome” in the plaintiff’s home country. Nine out of ten cases that suffer such a rebuff never get refiled. In the remaining few, “the Bhopal model is what corporations want to see.”

The outcome in Ecuador demonstrates, however, that this strategy is not without risk for corporations as well. “The Chevron litigation is a rare case when the company was not able to obtain a favorable outcome in a foreign system,” Simons continues. “When they couldn’t control the system they went on a rampage.” U.S. courts should not be allowing corporations to turn their backs on the U.S. justice system “and come crying back ten years later saying I didn’t get a fair hearing,” says Simons. “If you choose a foreign court you should bear the risk.”

In the rare cases when litigation for harm committed overseas has been allowed to proceed in the United States, some measure of justice has usually been achieved. Two key cases alleging human-rights abuses, one brought by Burmese laborers who’d been forced to work for Unocal (a California-based company that eventually merged into Chevron) and the other by Nigerians, including the widow of murdered activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, against the Royal Dutch Shell Company (based in the Netherlands), survived attempts at dismissal via forum non conveniens. As a result, both ended in settlements. These claims had been brought largely under the Alien Tort Statute, which gives U.S. federal courts jurisdiction to hear actions brought by foreigners who’ve experienced harm “in violation of the law of nations.” In 2013, however, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. (a case also involving Nigerians facing abuses for opposing oil extraction) on the grounds that the statute should be presumed to not apply to harms committed on foreign soil.

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts explained that should the U.S. attempt to exert its moral authority around the world, that “would imply that other nations, also applying the law of nations, could hale our citizens into their courts for alleged violations of the law of nations occurring in the United States, or anywhere else in the world.” The justices were concerned, surmises Hager, that should they accept the overseas application of international law they would facilitate the use of such law in foreign courts against U.S. corporations. The ruling, along with forum non conveniens and other doctrines, he observes in an email, “creates a safe haven behind the U.S. border” for U.S. corporations, enabling them to avoid justice for their actions in developing countries and giving them a competitive advantage over firms domiciled in, for instance, Europe. This July, a federal appeals court used the Supreme Court ruling to dismiss a case brought against Chiquita Brands International by Colombian survivors of massive human rights violations committed by a paramilitary group funded, in part, by the company.

In 2005, the European Court of Justice had clarified that national courts in the EU could not halt proceedings using forum non conveniens if the alternate court was outside the EU. As a result, several cases brought by foreigners against U.K.-based corporations have quickly and successfully reached conclusion, notes Richard Meeran, a lawyer who specializes in such litigation. In principle, Congress could act to make U.S. courts more hospitable to such litigation, by for instance similarly barring the use of forum non conveniens for domestic corporations, or by enacting legislation that explicitly enables the prosecution of corporations for overseas abuses. But no such bills are pending in Congress, nor would they have much of a chance of being passed. Hager concludes that an international treaty might be the only way to abolish egregious doctrines such as forum non conveniens.

In late June the United Nations Human Rights Council voted to begin developing a legally binding treaty that would regulate transnational corporations under international human rights law. Twenty countries voted for the resolution, sponsored by Ecuador and South Africa, but the United States and the EU lobbied and voted against it. A U.S. delegate reportedly said that no country that opposed such a treaty would be bound by it. If this is any indication of the prospects for obtaining justice for Bhopalis, afectados, and other foreigners who suffer grievous abuses at the hands of U.S. multinationals abroad, the future appears bleak.

Madhusree Mukerjee writes about science, environment, development, and indigenous issues. She is the author of two books, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II (Basic Books, 2010) and The Land of Naked People: Encounters with Stone Age Islanders (Houghton Mifflin, 2003).

* Update: On November 15, 2014, a minister of the Government of India responded to a prolonged hunger strike by Bhopal survivors by promising to review the death and injury figures in the curative petition. The revision, which is to be based on the extant medical evidence, would presumably also lead to an increase in the financial claims on Dow. Furthermore, the minister promised to seek an expedited hearing of the amended curative petition, which has not been heard even once since it was filed on December 3, 2010.