The University and the Company Man

The University and the Company Man

Not so long ago, the social contract between workers, government, and employers made college a calculable bet. We built a university system for the way we worked. What happens to college when that social contract is broken—when we work not just differently but for less? And what if the crisis in higher education is related to the broader failures that have left so many workers struggling?

The U.S. higher education crisis has been well documented. College is overpriced, over-valued, and ripe for disruption (preferably, for some critics, by the outcome-driven private sector). At the same time, many Americans are flailing in the post-recession economy. With rising income inequality, persistent long-term unemployment, and declining real wages, Americans are searching for purchase on shifting ground. Not so long ago, the social contract between workers, government, and employers made college a calculable bet. But when the social contract was broken and policymakers didn’t step in, the only prescription for insecurity was the product that had been built on the assumption of security. We built a university system for the way we worked. What happens to college when we work not just differently but for less? And what if the crisis in higher education is related to the broader failures that have left so many workers struggling?

There is a lot of talk right now about how we will work in the future, but it’s mostly based on the realities of how we work today. Many express concerns about the quality and quantity of “good jobs,” which sociologist Arne Kalleberg has characterized as jobs that pay a living wage, are on a ladder of career opportunity, and provide all the material benefits that make for economic security (such as retirement funds and health care). Beneath the surface of debates about yawning income inequality are empirical arguments about job polarization—the idea that the labor market is being pulled at both ends like taffy by global competition, technological change, and policy. At one end are high-skill, high-paying “good” jobs. At the other end are low-skill, low-paying “bad” jobs. The middle, meanwhile, is getting thinner and thinner. And job creation—as underwhelming as it is—is not evenly distributed among the jobs people want and the jobs people have to take. There are more bad new jobs than good. Economists Nir Jaimovich and Henry Siu argue that in the 1980s jobs with lower skill requirements (and pay) started to increase their share of the labor market. That trend has only picked up after the great recession.

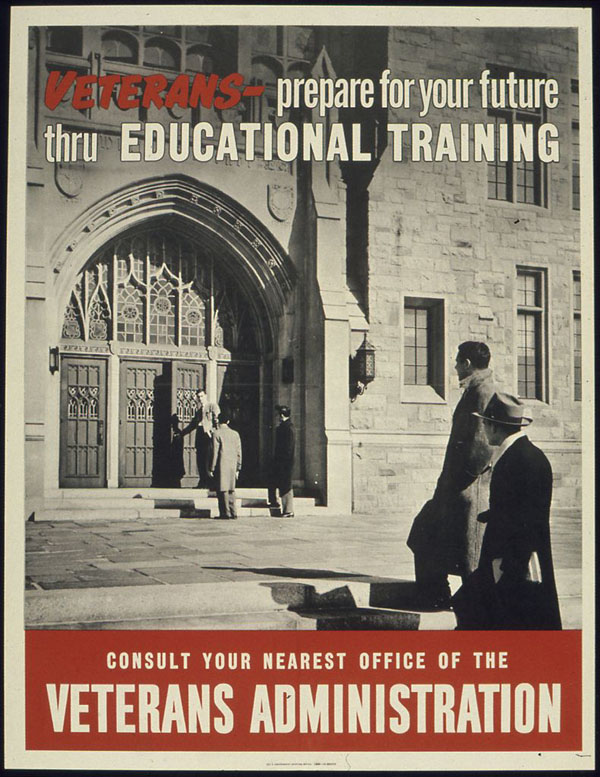

What does this have to do with higher education? That depends on what you think jobs have to do with degrees. Sociologists and economists think the two are inextricably linked, even if they disagree how and to what extent. Historically, the expansion of higher education mapped onto the expansion of the economy, not just in terms of the number of jobs but also their quality. The Second World War is often cited as the backdrop for the great expansion of higher education attainment. The G.I. Bill ramped up college access for men (and, later, women) in historic numbers. Public universities, in particular, responded to meet this demand.

But college wasn’t just expanding to meet increasing demand for college degrees. It was also expanding to keep pace with the expansion of the labor market, and in particular the growth of stable, middle-class jobs. Written in the 1990s, Anthony Sampson’s Company Man chronicles the rise and fall of the middle-class corporate work arrangement forged during the expansion of the economy in the 1950s. The corporate loyalty of this “company man”—and woman—was rooted in the security and identity afforded by the company’s investment in workers. In exchange for curtailed autonomy, the company man received annual bonuses, semi-regular job promotions, a schedule that had him home for dinner most nights, and the promise of a secure retirement. In short, the “good jobs” economists say are increasingly unavailable in our bifurcating labor market were the offspring of a 1950s social contract between workers and corporations. To say things have changed is an understatement.

But college wasn’t just expanding to meet increasing demand for college degrees. It was also expanding to keep pace with the expansion of the labor market, and in particular the growth of stable, middle-class jobs. Written in the 1990s, Anthony Sampson’s Company Man chronicles the rise and fall of the middle-class corporate work arrangement forged during the expansion of the economy in the 1950s. The corporate loyalty of this “company man”—and woman—was rooted in the security and identity afforded by the company’s investment in workers. In exchange for curtailed autonomy, the company man received annual bonuses, semi-regular job promotions, a schedule that had him home for dinner most nights, and the promise of a secure retirement. In short, the “good jobs” economists say are increasingly unavailable in our bifurcating labor market were the offspring of a 1950s social contract between workers and corporations. To say things have changed is an understatement.

In his 2006 book, The Great Risk Shift, Jacob Hacker explores “the new economic insecurity and the decline of the American dream” by measuring the shift of risk from corporations to individuals. He focuses on three trends: the erosion of company-paid pensions, the declining value of corporate-subsidized health benefits, and the use of layoffs to manage company bottom lines. To take the example of pensions: the National Institute on Retirement Security reports that in 1975, 88 percent of private sector employees had a pension plan wherein the company guaranteed benefits, but by 2005 that number was 33 percent. Rather than eating the cost of the company man’s inevitable aging, the private sector shifted the costs of old age onto individual workers, replacing pensions with individual worker-funded investment accounts like 401(k)s and the security of the organization with the volatility of the stock market.

In The Two Income Trap: Why Middle Class Parents are Going Broke, Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Warren Tyagi describe how this shift of risk to workers has changed our family lives, with rising child care and education costs driving middle-class families into economic crisis. The continuing downward pressure on wages has made things look even worse today than in 2004, when the book was first published: Warren and Tyagi didn’t consider the extra costs borne by families paying not only for their children’s tuition but their own further education, in order to stop the decline in their wages.

In its latest annual survey of incoming college freshmen, the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) reports that an all-time high number—87.9 percent—cited “to be able to get a better job” as a very important reason for going to college. Going to college for a job is not a new idea, but the desire for a “better” job could explain why so many are willing to pay so much for college, with total national student loan debt now exceeding $1 trillion.

In the 1950s the labor market presented us with a social contract, and higher education responded. But the economic forces that brought us the great risk shift killed the company man.

That burden isn’t just carried by young adults. With job insecurity and competition for good jobs on the rise, the typical college student is now older, browner, and more likely to be caring for a family. And because life doesn’t stop when you decide to go to college, many of the growing number of older, non-traditional students have turned to for-profit schools, which have excelled at providing options for those who must fit college into their existing lives. For-profit colleges like ITT Tech and the University of Phoenix are among the most expensive places to get a degree in the United States, and their students carry some of the highest student loan debts. The president of for-profit DeVry University once said that most of the school’s incoming students report that they are going to college because they’ve been laid off or suspect they will be soon. Like the mostly traditional college students in the HERI report, older students are also going to college hoping for a better job. And even though fewer “better” jobs are available, many are willing to pay almost anything for the opportunity to get one. As countless researchers and politicians and parents will tell you, a worker with a college degree will still earn more than a worker without one, despite the erosion of the corporate social contract of the 1950s.

But “more” is relative. In a report titled, “College is Still the Best Option,” the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University shows that “holders of college degrees earn on average twice as much as high school graduates in 2008.” That is the primary takeaway for countless pundits, but the reality is more complicated. As the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) pointed out in a brief corrective to the above report, “the premium for people with just a college degree, compared to those without a college degree, has been almost flat for two decades.” And in a report on findings from labor economist David Autor in 2010, the Chronicle of Higher Education reminded us that an income divide isn’t just about the premium for education: “the growing gap between high-school and college wages has more to do with the declining earnings of high-school graduates than big gains for college completers.” The college wage premium looks pretty good when the floor is being lowered, but even that premium isn’t the same for all degree holders. As CEPR’s Dean Baker has pointed out, “almost all of the increase in the gap [between degree holders and non-degree holders] during this period has been due to wage growth for those with advanced degrees.”

The current narrative from the private sector and elite opinion-makers is that higher education is failing Americans. College is overpriced and due for disruption. Graduates are not prepared for their jobs, and rigid class schedules make it hard for workers to retrain for twenty-first-century jobs. But just thirty short years ago, the wage premium for college graduates was being touted as the saving grace of higher education. How could college have gone so wrong so fast?

In our college system, we must place sucker bets. The “opportunity costs” of spending four to six years not being employed while you earn a degree were once measured against the security promised by the corporate social contract. Now, workers must not only absorb the costs of retirement planning, health care, and child care but also educate themselves to satisfy a moving target. There is plenty to be said about expensive climbing walls at pricey colleges and the often inadequate choices that the poor have, but there is no reason colleges cannot prepare workers for how we work today. Between 1945 and 1965 the entire system of higher education reinvented itself, in large part to give corporations the company men they needed. Higher education surely knows how to change—when it knows what it is changing to.

And therein lies the rub. We know that there are fewer and fewer good jobs, but we are unsure of what will replace them. In The Second Machine Age, Andrew McAfee and Eric Brynjolfsson take a stab at predicting how technology will change the way we work (and, consequently, live). Even if the promised wonderful jobs of the future do emerge, McAfee and Brynjolfsson predict that “in the short term income gaps will widen.” It seems a safe prediction to make considering current economic trends: the fastest-growing segments of the labor market offer more bad jobs, and for less pay. Colleges are now open to more Americans not born to wealth than ever before, but they are better at moving people from bad jobs to the better jobs in the middle than to the shrinking number of good jobs. With fewer landing spots in the middle, the structure becomes less sound. This is the question buried in the rhetoric about the higher education crisis: what is college when there is no middle?

Some colleges are doubling down on serving the most elite, most well-prepared students. Those students, through a combination of ability and fortune, will end up in high-skilled good jobs. But there aren’t enough of those spots to go around. For the rest of us, the prescription for insecurity is more college, but colleges do not know what work to prepare us for. In the 1950s the labor market presented us with a social contract, and higher education responded. But the economic forces that brought us the great risk shift killed the company man. For those of us looking for economic security who are not fortunate or able enough to be fast-tracked into the good jobs, there isn’t much college can do.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is a sociologist and writer in Atlanta, Georgia, where she is finishing her PhD at Emory University. She has two books forthcoming on privatized higher education and inequality. She can be found at www.tressiemc.com and on Twitter @tressiemcphd.