Postcards from Empire

Postcards from Empire

At the height of colonialism, indentured Indian women in the Caribbean were photographed for a thriving postcard industry. Their images enact a struggle—between the imaginations of colonial-era photographers and the real lives of the women behind the portraits.

In the photograph a young woman poses against a stately painted backdrop, a balcony with elegant fretwork and a sylvan view. She cocks her head demurely to one side, a solitary finger touching her jaw. A rose-patterned garment moulds her figure and covers her head, but her feet are bare. An elaborately braceleted arm closes around her waist, almost defensively. The unnamed woman’s eyes gaze softly back at the viewer, a faint smile playing on her lips.

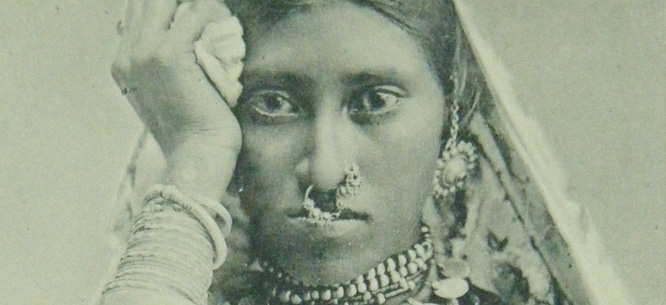

Victorian-era photographs of Indian women in the West Indies advertized their beauty and their prosperity. Almost always, the women depicted are laden with silver and gold, their bodies showcases for jewelry from “the East.” Like the woman described above, they wear the bells of jhumkas in their earlobes, diadem-like matha pattis along the part in their hair, rings in their noses, and widening gyres of gold florins around their necks. Bangles and metal bands cover every inch of their arms. The trinkets give the women a primitive, tribal quality, but they also suggest opulence and the exotic.

I discovered these photographs on tourist postcards while researching the repressed history of Indo-Caribbean women for Coolie Woman, a book that doubles as a family history. This stunning visual archive, mainly featuring images from Trinidad from the 1870s to the 1890s, included dozens upon dozens of studio portraits of Indian women dressed in flowing ghararas and adorned with ornate jewelry, caught in many moods and postures, their heads covered or bare, expressions coy or brazen, miserable or defiant, smiling or pointedly not.

Often, the postcards carry captions or even hand-written notes suggesting how people may have identified or perceived the portraits at the time. Many were simply titled “Coolie Belle.” One from Trinidad reads: “Dressed Coolie Woman. All Gold.” Another describes its subject as: “A wealthy coolie woman awaiting her husband.” On one postcard, the daughter of an American missionary in British Guiana scribbled to a friend: “This gives a good idea of their costumes. The women wear round flat yellow metal ornaments on the side of the nose, three or four silver bracelets on each arm, and often silver bracelets on each ankle.”

The text accompanying the postcards reflects a preoccupation with how these women looked, especially with their jewelry and the wealth that it suggested. But the irony of the word “coolie”—conventionally used to refer to manual laborers on the Indian subcontinent—being juxtaposed with such riches was clearly lost on the caption writers. In these plantation societies on the verge of becoming tourist paradises, the word had acquired a new meaning—as ethnic slur. Any Indian woman in the West Indies, whatever her status, however she earned a living, was reducible to a “coolie belle.” The phrase, while highlighting her physical charms, also marked her as a permanent foreigner in the Caribbean, forever branded with her origins as an Indian import.

Between 1838 and 1917 Indian women came to the Caribbean as “coolies,” indentured laborers used by the British to replace emancipated slaves on plantations throughout the empire. The traffic in indentured labor was one third the size of the British slave trade, with more than a million Indians shipped to roughly a dozen colonies worldwide. Despite its scale, the history of indenture—neglected as a postscript to the abolition of slavery—has been largely lost to collective memory. Especially unknown are the viewpoints of the indentured themselves, how they experienced a system that economically and sexually exploited them, and that inflicted untold misery upon them and their descendants.

Only two memoirs about indenture exist; both were authored by men. A majority of the quarter of a million women transported by the British as “coolies” were widows and other outcasts traveling without husbands by their sides; they were dispossessed, marginalized, and anonymous. Few were literate (in English or in any Indian language) and they left behind no letters, diaries, memoirs, or other written testimonies. Rather than speaking for themselves in the historical record, they were spoken for—coolie women are described by countless government officials and the authors of fanciful narratives, almost all of them white men. An extensive paper trail—colonial travelogues, captains’ logs, ship surgeons’ diaries, and confidential Colonial Office dossiers on errant overseers—provides evidence of the women’s physical lives, but does not—indeed cannot—reveal much about what they thought or felt.

The interior lives of these women went undocumented, but their bodies did not—the written archives are filled with descriptions of both their physical allure and the physical trauma they suffered. But what distinguishes the colonial photographs of indentured women as a historical source is that, unlike descriptions found in a traveler’s tale or an immigration agent’s report, we see them, and they—seemingly—look back at us. These images don’t simply document, they enact a struggle—between the imaginations of colonial-era photographers and the real lives of the women behind the portraits. In doing so, they suggest a radically different perspective on imperial history.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Indian women were photographed in Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana for a thriving postcard industry built on marketing the Caribbean as a holiday destination for Western tourists. During the colonial period, the Caribbean islands had developed a reputation as hot-houses of hard drink and yellow fever, virtual graveyards for white men. Determined to change this perception, colonial administrators launched a concerted campaign to sell the Caribbean as an “exotic but safe” destination, a message well represented by images of beautiful women who were once among the British empire’s most denigrated laborers.

Fortuitously for colonial officials, the rise of tourism in the 1890s coincided with technological advances that made photography more accessible to the general public—like George Eastman’s invention of the Kodak box camera in 1888. In the Caribbean, the camera swiftly came to be associated with tourists. Even Jamaica’s Daily Gleaner declared in 1901: “Oh who would be a tourist / and with the tourists stand / A guide-book in his pocket / A Kodak in his hand!”

Various businesses were happy to profit from the tourist boom, and so the images achieved wide circulation. The United Fruit Company, haberdasheries, and newspapers subsidized postcards that subliminally promoted the colonies as tropical paradises while directly advertising their own companies through sponsored tag-lines. Professional photographers marketed the Caribbean as “picturesque,” and therefore, as worthy of being photographed; this in turn inspired tourists with their Kodaks. Meanwhile, studios continued to thrive by processing amateur snaps as well as selling their own scenic views and portraits of local people as filler for vacation albums.

As interconnected as colonial photography became with tourism, it was deeply tied to imperialism from the start. Not long after Louis Daguerre made the details of the photographic process publicly available in 1839, it was used in the service of the pseudo-science of race. The first daguerreotypes compared slaves in South Carolina to slaves in Brazil in a format that became generic: “specimens,” often naked, were photographed from the front, back, and side, focusing on their anatomy and physical characteristics in order to document perceived racial differences. At about the same time and with similar ethnographic intentions, British colonial administrators in India commissioned a photographic field survey of the subcontinent’s tribes, castes, and cultures, published as the multi-volume The People of India.

International colonial exhibitions held from 1850 to 1915 in Europe, North America, New Zealand, and Australia provided another forum for these images. Drawing millions of viewers, the exhibitions were originally intended to display industrial products and gadgets, an early form of mass merchandising. But by the 1880s, the exhibitions became less about economic ventures and more about disseminating theories of scientific racism then in vogue, through photos and live displays of “curious” peoples that objectified colonized subjects as inferior and backward, even savage. The Caribbean postcards of indentured women bear traces of this lineage.

A closer examination of the photographs suggests that these images were subtly controlled by the men behind the cameras, rather than simple representations of the women who posed. Several of the “coolie belles,” for instance, appear to be wearing the same flowered orhni or veil draped over their heads and across their waists. Western photographs of geishas in late nineteenth-century Yokohama possess similar telltale signs of staging: a recurring kimono, suggestively falling off one shoulder, sometimes revealing a breast. The reappearing item of clothing hints at manipulation by photographers who were perhaps creating images not for their subjects, but for others: tourists or seekers of soft porn.

The photographer who produced many of the images still surviving in the hands of collectors or libraries was the Frenchman Felix Morin. From 1869 to the late 1890s he maintained a studio along a main shopping artery in the Trinidadian capital of Port of Spain, next to a landmark Anglican church where tourists would have found him easily. His ad in Stark’s Guide-Book and History of Trinidad, published in Boston in 1898, began with a direct appeal: “To Travellers.” Promising “Curios of All Sorts” and “Special Views Taken to Order,” Morin invited these prospective clients to peruse “The Finest Collection of Tropical Sceneries, Types and Costumes, Interior of Guiana, Etc.” Readers of Stark’s illustrated survey could also find several ethnographic portraits by Morin; his images of Hindu priests, a “Coolie Man and Wife” and a “Coolie Belle” gilded the guidebook. This last “type” seemed to be his favorite subject. Morin sold many cartes de visites featuring Indo-Caribbean beauties as souvenirs. The women posing did not pay for them; rather, commercial sponsors and tourists did.

Unlike early daguerreotypes of naked specimens, Morin’s belles were clothed (mostly ostentatiously). But his portraits of coolie women share certain similarities with stock images from other islands. In her analysis of images from Jamaica and the Bahamas in An Eye for the Tropics (2006), art historian Krista Thompson contends that they depicted tamed nature and disciplined natives. By showing orderly rows of palm trees, donkeys burdened with bananas, and black washerwomen at work, Thompson argues that such images offered “visual testaments to the effectiveness of colonial rule.” They were intended to “convince primarily white travelers to the majority black colonies that the ‘natives’ were civilized” and posed no danger. Morin’s portraits performed a similar function: the youthful, lovely, lavishly ornamented women in his photographs were meant both to entice and to reassure potential travelers to the Caribbean. His creative collusion with the rhetoric of empire was eventually rewarded with a bronze medal at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London and an honorable mention in the 1878 Paris exhibition.

It is perhaps fitting that Morin was both photographer and land surveyor; before staking a claim to territory, one has to map it. In a sense, his photographs of resplendent, thriving Indian women offered visual affirmations of imperial expansion: “coolie belles” were no doubt sexualized ethnic types, but in Morin’s photographs, they also appeared wealthy, suggesting that Indian women in the West Indies had done well to leave India. By portraying prosperous outcomes, the photographs arguably justified indenture while simultaneously erasing the fact of its existence. The women were posed in the studio against painted backdrops rather than in their lived landscapes of sugarcane fields and ramshackle plantation barracks. The postcards mostly airbrushed the squalor and the exploitation, effacing the physical background where they worked and lived.1

Still, some photographs show signs of resistance. The eyes of a woman cradling a vase seem to flash contempt. “Coolie belles” gaze back with pain or melancholy as often as with mischief or play, even as one might stand jauntily beside decorative columns or provocatively dangle a cigarette. The jewelry worn by photographed women also challenges the message of empire’s orderly success that the era’s photographers tried to convey.2 In the competition for scarce women, offering such necklaces—which often cost an Indian man his savings, and were sometimes fashioned from the actual coins in which he was paid—proved one way for a suitor to prevail. But for those who knew the troubled history of “coolie” intimacy, these ornaments betrayed the chaos that indentureship inflicted on Caribbean societies.

Women made up less than 30 percent of Indian plantation workers during the period of indenture. Because they were scarce, they were sought after, sometimes taken by force and sometimes leveraged, by both Indian and white men. Fathers extracted bride prices for their daughters, while plantation staff assigned or re-assigned women to new husbands to punish or reward male workers. Sometimes, the women themselves took advantage of their own scarcity; they could choose one man over another, even trade up in relationships to men with more money or status in either the plantation or caste hierarchy.

But this was not without its own consequences. Many women were attacked by the men they refused, with machetes meant to cut cane instead claiming noses, ears, and arms. Jewelry—like that worn by many postcard “coolie belles”—was often cited by colonial officials as a motive for murders by machete; when things fell apart, the desire to reclaim the jewelry may have fueled violence as much as the desire to punish dishonor. In colonies across the globe, hundreds of women were killed in this manner by their partners during the indenture period. Newspaper articles and coroner’s reports catalogued the victim’s injuries in grim detail: the precise number of wounds, the inches they bit into a skull or cheekbone, the specific body parts lopped. A century after indenture’s end, brutal domestic assaults against women continue in the West Indies; frequently, they are fatal. Often, the same weapon is used and the same motive—jealousy—is cited.

Some of the conditions that historically shaped the lives of “coolie women” endure, and not only in the Caribbean. Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen argued in 2013 that regions in India (and elsewhere) with shortages of women are at higher risk of gender-based violence, a problem prophesied by the historical example of indentured women. Indenture-like conditions and contracts still fetter immigrant laborers (many of them South Asians) in the Persian Gulf. Descendents of indentured laborers—including the large Guyanese diaspora in New York City3—continue to struggle with social problems rooted in indenture and colonialism: alarming rates of intimate partner violence, alcoholism, poverty, and gender inequality.

The legacy of exploited female labor continues to haunt the imagination, too. Last summer, artist Kara Walker exhibited A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an installation at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn. Her colossal sculpture, created from white sugar crystals, showed a naked black woman recumbent like a Sphinx, her private parts swollen and exposed, her babies hefting baskets of molasses around her. Walker’s work referenced the ways—economic, sexual, and reproductive—in which the bodies of women of color were used in colonial sugar economies.

In a sense, there is mordant, poetic justice in the fact that what befell the bodies of our female ancestors says more about their condition than they themselves could. Who “coolie women” were—and who we, their descendants, are—is at its heart a story about the demand for women’s bodies, for labor, for sexual gratification, and for procreation. (This, too, was work: their wombs were factories for future workers.) The ongoing violence against women in the Caribbean challenges now, as it did then, popular narratives of the region as a getaway. It is an escape only for some.

Initially, the travel postcards of the Caribbean represented the power of colonizer over colonized—they were taken at the behest of imperial officials to further their goal of marketing the colonies as tourist destinations. But as time passed and photography became more affordable, subjects gradually exerted more control over images of themselves. Around 1900, the descendants of the indentured—and some of the formerly indentured—began to sit for photographs as customers, choosing their own dress and backdrops.

These images, handed down by families, provide a striking contrast to the postcard images. Those who could afford it posed in studios with their Sunday best—often Western-style suits—but many sat for portraits at home. Instead of faux backdrops with Grecian pillars, potted plants, or wrought-iron railings, these family photos show simple, realistic settings: rough-hewn walls fashioned out of greenheart timber, wild bush surrounding Spartan village houses, even the shoddy, warehouse-style hovels in plantation yards. Instead of opulently dressed “coolie” women posing by themselves, these portraits show women wearing modest clothes with sparse jewelry. Their adornments are the grandchildren on their laps, their husbands and sons, their mothers and sisters by their sides. What the images display, when subjects paid and chose how they were photographed, was the importance of family—an institution in ruins during indenture. When figures like Morin weren’t asking them to, they didn’t pose alone, but surrounded by kin. With these family portraits, women weren’t simply sexualized objects but individuals with relationships, revealed through the cradling of a toddler, a hand touching a shoulder, or a bridal bouquet grasped.

The poet Mahadai Das was known in intellectual and artistic circles in New York and Chicago in the 1980s, but she was from a small place well off the literary map: Guyana, the former British plantation colony along South America’s northeastern coastline. That obscure, troubled nook reclaimed her after heart trouble derailed her doctoral studies in philosophy at the University of Chicago. Through letters since lost, word reached Brooklyn that for a dark time back in her country, a car was her home. The daughter of a rice farmer who was accepted as an undergraduate at Columbia University, Das had traveled from the world’s margins to its most powerful metropolis and back.

Her journey out had been unorthodox. She had been both beauty queen (crowned Miss Diwali at seventeen at a Hindu festival in Georgetown, Guyana) and paramilitary volunteer (she donned fatigues and farmed cotton in service to a new nation reimagining itself as a “cooperative socialist republic”). Like me, Das was an Indian woman born in the West Indies, a granddaughter of indentured women. Her work explores themes of mortality, thwarted love, migration, postcolonial patriotism. Throughout flash images of the female body: bejeweled, uniformed, laboring, diseased, childless, desiring and desirable, as her own body had once been and much as the bodies of “coolie” women once were.

Her poetry serves as an alternative imaginarium, a rival source like the family portraits, illuminating a hidden chapter of colonial history from the perspective of those who suffered its wounds. In the haunting and macabre “Beast,” one of a handful of poems by Das in which she directly engages with the subject of indenture, she writes:

. . . pirates in search of El Dorado

masked and machete-bearing

kidnapped me.

Holding me to ransom,

they took my jewels and my secrets

and dismembered me.

The reckoning lasted for years.

Limbs and parts eventually grew:

a new nose, arms skillful and stronger,

sight after the gutted pits could bear a leaf.

It took centuries.

Das doesn’t explicitly mention the historical murders, but the machete that flashes between her lines evokes the violence against indentured women as well as the widespread plunder that accompanied colonialism. Her poem refers to the first British encounter with the region, an explorer’s foray but also an imperial one: Sir Walter Raleigh was in search of El Dorado and its golden loot when he landed in the Guianas in 1594. In folk songs and stories told by the indentured three centuries later, the British in India feature as kidnappers of women, because they, even more than men, resisted recruitment as plantation laborers for a number of cultural and economic reasons. British seamen and overseers, who raped and exploited indentured women on ships and plantations, were literally and metaphorically responsible for stealing their “jewels” and their “secrets.” In the poem, Das accuses European colonizers of doing some “dismembering” of their own—severing the indentured from their country and kin, much like the Indian men who literally turned machetes against their partners. Through the imagery of lost body parts that take centuries to recuperate, Das alludes to one of indenture’s most brutal legacies.

Das’s life was cut tragically short when she died of a heart attack in 2003, at the age of forty-eight. Heiress to so much muted history, she was herself silenced in many ways. For more than a year after suffering a stroke, she lost her voice, described as “gentle but dangerous” by a Trinidadian poet in New York who knew her. Her letters to friends in Brooklyn, detailing her creative and material hardships, were also discarded by accident. Published by her paramilitary unit and small independent and radical presses, Das’s work never reached a wider audience. But she remains a pivotal figure, one of only a handful of Indo-Caribbean female writers to emerge even now, a century after indenture’s end. A ventriloquist for our female ancestors, Das remains a rare voice in an otherwise silent archive.

Gaiutra Bahadur is the author of Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture (University of Chicago Press, 2013), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Orwell Prize.

1. Scholars Krista Thompson, Joy Mahabir, and Anna Arabindan-Kesson have made similar observations about how the imperial postcard images fail to depict Indian women as plantation laborers.

2. Others, like Mahabir, have also remarked on the staging of the photographs and the jewelry worn by Indo-Caribbean women, with differing interpretations over their significance (for example, see “Alternative Texts: Indo-Caribbean Women’s Jewelry,” 2014).

3. Guyanese are the fifth largest immigrant group in New York City.