Plutocrats at Work: How Big Philanthropy Undermines Democracy

Plutocrats at Work: How Big Philanthropy Undermines Democracy

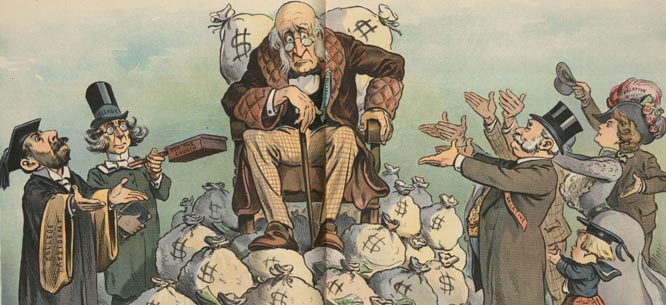

Early twentieth-century skeptics were rightly suspicious of plutocrats deciding how to improve the human condition and then paying to translate their notions into public policy. Now it’s time for a new progressive era—complete with muckrakers and trust-busters to cast a critical eye on big philanthropy.

Big philanthropy was born in the United States in the early twentieth century. The Russell Sage Foundation received its charter in 1907, the Carnegie Corporation in 1911, and the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913. These were strange new creatures—quite unlike traditional charities. They had vastly greater assets and were structured legally and financially to last forever. In addition, each was governed by a self-perpetuating board of private trustees; they were affiliated with no religious denomination; and they adopted grand, open-ended missions along the lines of “improve the human condition.” They were launched, in essence, as immense tax-exempt private corporations dealing in good works. But they would do good according to their own lights, and they would intervene in public life with no accountability to the public required.

From the start, the mega-foundations provoked hostility across the political spectrum. To their many detractors, they looked like centers of plutocratic power that threatened democratic governance. Setting up do-good corporations, critics said, was merely a ploy to secure the wealth and clean up the reputations of business moguls who amassed fortunes during the Gilded Age. Consider the reaction to John D. Rockefeller’s initial request for a charter from the U.S. Senate (he eventually received one from New York State):

In spite of his close ties to big business, Progressive presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt opposed the effort, claiming that “no amount of charity in spending such fortunes [as Rockefeller’s] can compensate in any way for the misconduct in acquiring them.” The conservative Republican candidate, William Howard Taft denounced the effort as “a bill to incorporate Mr. Rockefeller.” Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, sneered that “the one thing that the world would gratefully accept from Mr. Rockefeller now would be the establishment of a great endowment of research and education to help other people see in time how they can keep from being like him.”*

*Peter Dobkin Hall, “A Historical Overview of Philanthropy, Voluntary Associations, and Nonprofit Organizations in the United States, 1600–2000,” in The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, Yale University Press, 2006, 47.

The social policy ideas of the new foundations were shaped by their understanding of modern research-based medicine, especially germ theory. Scientists aimed not simply to alleviate symptoms but to discover the nature of a disease, isolate the pathogen, then develop and administer a cure. Private philanthropies planned to do the same for such social ills as poverty and illiteracy: sponsor research on a problem, finance the design of a remedy, and pay for implementation (sometimes with the addition of public funds). The foundation trustees seemed unaware that social problems are too multifaceted, too historically rooted, and too entangled in politics and the economy to conform to the medical model. Of course, the new general-purpose foundations didn’t focus exclusively on social issues. They funded the “hard” sciences, projects in international relations, and more. But rooting out social problems was one priority.

One hundred years later, big philanthropy still aims to solve the world’s problems—with foundation trustees deciding what is a problem and how to fix it. They may act with good intentions, but they define “good.” The arrangement remains thoroughly plutocratic: it is the exercise of wealth-derived power in the public sphere with minimal democratic controls and civic obligations. Controls and obligations include filing an annual IRS form and (since 1969) paying an annual excise tax of up to 2 percent on net investment income. There are regulations against self-dealing, lobbying (although “educating” lawmakers is legal), and supporting candidates for public office. In reality, the limits on political activity barely function now: loopholes, indirect support for groups that do political work, and scant resources for regulators have crippled oversight.

Because they are mostly free to do what they want, mega-foundations threaten democratic governance and civil society (defined as the associational life of people outside the market and independent of the state). When a foundation project fails—when, say, high-yield seeds end up forcing farmers off the land or privately operated charter schools displace and then underperform traditional public schools—the subjects of the experiment suffer, as does the general public. Yet the do-gooders can simply move on to their next project. Without countervailing forces, wealth in capitalist societies already translates into political power; big philanthropy reinforces this tendency.

Although this plutocratic sector is privately governed, it is publicly subsidized. Private foundations fall into the IRS’s wide-open category of tax-exempt organizations, which includes charitable, educational, religious, scientific, literary, and other groups. When the creator of a mega-foundation says, “I can do what I want because it’s my money,” he or she is wrong. A substantial portion of the wealth—35 percent or more, depending on tax rates—has been diverted from the public treasury, where voters would have determined its use.

The main rationale for both the tax exemption and the charitable contribution tax deduction (created in 1917) is to stimulate private giving. Yet this is a weak rationale when applied to the super-rich; a more effective way to stimulate their giving would be to raise the estate and capital gains taxes. It is a meaningless rationale for the 65 percent of American taxpayers who don’t itemize their deductions and therefore can’t use the charity tax break.

Despite scores of studies, the relationship of charitable giving to tax incentives remains unclear. Too many different factors determine giving: religiosity, innate altruism, family tradition, social attitudes, community ties, alumni loyalty, fluctuations in income. But other patterns of giving are well known. Less than 10 percent of all charity in the United States addresses basic human needs. The wealthiest donors devote an even tinier portion of their giving to these needs. Most major donations go to universities and colleges, hospitals, and cultural institutions, often for highly visible building projects carrying the donor’s name (New York Times, September 6, 2007).

Another public subsidy to private foundations comes from the “5 percent minimum payout requirement.” To prevent private foundations from hoarding all their wealth, the 1969 tax reform requires them to make grants annually that equal or exceed about 5 percent of their endowment’s value. There is, however, a loophole. The payout includes all “reasonable” foundation administrative expenses—from salaries and trustee fees to travel, receptions, office supplies, equipment, rent, and new headquarters. Only the cost of financially managing the endowment is excluded. Thus an extravagant “lifestyle” can cost a wealthy foundation nothing: any part of the 5 percent payout that a foundation doesn’t spend on itself must go to grants anyway.

Right now, big philanthropy in the United States is booming. Major sources of growth have been the wealth generated by high-tech industries and the expanding global market. In September 2013 there were sixty-seven private grant-making foundations with assets over $1 billion. The Rockefeller Foundation, once the wealthiest, now ranks fifteenth; the Carnegie Corporation ranks twentieth (Foundation Center).

Mega-foundations are more powerful now than in the twentieth century—not only because of their greater number, but also because of the context in which they operate: dwindling government resources for public goods and services, the drive to privatize what remains of the public sector, an increased concentration of wealth in the top 1 percent, celebration of the rich for nothing more than their accumulation of money, virtually unlimited private financing of political campaigns, and the unenforced (perhaps unenforceable) separation of legal educational activities from illegal lobbying and political campaigning. In this context, big philanthropy has too much clout.

Without countervailing forces, wealth in capitalist societies already translates into political power; big philanthropy reinforces this tendency.

In the twentieth century, public distrust and the occasional congressional investigation encouraged big philanthropy to keep a lower profile. The foundations were generally cautious about public policy partisanship, discreet about government ties, and shy of politics. (A notorious exception was the Ford Foundation’s experiment in community control of schools in New York City’s Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhood in 1968.) Today’s context permits a radically different style: publicity-seeking, programmatically aggressive, and pushing against the remaining limits on political activity. The “out-there” mega-foundations are usually those overseen by living donors, people who made enormous fortunes running businesses in recent years. The mantras of twenty-first-century big philanthropy are strategic giving, return on investment, grantee accountability, numerical data to verify results, social entrepreneurship, and public-private partnership. This business-style philanthropy is often called “venture philanthropy” or “philanthocapitalism.”

The roles of grantor and grantee have also changed. Once upon a time, the mega-foundations established a goal and sought experts to do independent research on how to achieve it. Today many donors and program officers have preconceived notions about social problems and solutions. They fund researchers who are likely to design studies that will support their ideas. Instead of reviewing proposals from outside the foundation, they hire existing nonprofits or set up new ones to implement projects they’ve designed themselves. The mode of operation is top-down; grantees serve their funders. Mega-foundations also devote substantial resources to advocacy—selling their ideas to the media, to government at every level, and to the public. They also directly fund journalism and media programming in their fields of interest. All this marks a cultural transformation of big philanthropy.

The power relationship between grantor and grantee has always been one-sided in favor of the grantor. Sycophancy is built into the structure of philanthropy: grantees shape their work to please their benefactors; they are perpetual supplicants for future funding. As a result, foundation executives and trustees almost never receive critical feedback. They are treated like royalty, which breeds hubris—the occupational disorder of philanthro-barons. By taking over the roles of project originator and designer, by exercising top-down control over implementation, today’s mega-foundations increasingly stifle creativity and autonomy in other organizations. This weakens civil society. Some mega-foundations even mobilize to defeat grassroots opposition to their projects. When they do, their vast resources can easily overwhelm local groups. This, too, weakens civil society.

To be clear, I’m criticizing both the excessive influence of mega-foundations on public policy and the fact that they are publicly subsidized. In a free society, the super-rich can spend their money in any legal way they want, including endowing huge organizations to try out pet theories and promote personal projects. But those organizations shouldn’t be tax exempt. The super-rich don’t need billions of dollars in tax relief annually to exert their will in the public sphere. They can, and most will, engage in the same activities without the government handout. Although redistributing power more fairly throughout society will require campaign finance reform and rigorous progressive taxation, there’s no reason to continue to subsidize big philanthropy.

According to the Foundation Center (in an email to the author), private grant-making foundations in the United States numbered 73,764 in 2011. Most are small. In the last fiscal year, only 1,293 of them (1.8 percent) had assets of $50 million or more. Small foundations don’t have the resources to mount massive social experiments, dominate the national debate on issues, or suffocate citizen activity. They likely need tax-exempt status to survive. When they fund modest-sized pilot projects and focus on under-resourced populations, when the research is solid and a foundation collaborates with (rather than dictates to) participants, there’s a chance to discover innovative public policies. If a pilot project clearly succeeds, democratically elected officials should decide whether or not to scale it up. If it fails, the foundation should repair any damage. Mega-foundations could operate in this way, and some do fund small-scale independent projects. But the size and culture of big philanthropy now militate against this.

The Case of Public Education

For a dozen years, big philanthropy has been funding a massive crusade to remake public education for low-income and minority children in the image of the private sector. If schools were run like businesses competing in the market—so the argument goes—the achievement gap that separates poor and minority students from middle-class and affluent students would disappear. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation have taken the lead, but other mega-foundations have joined in to underwrite the self-proclaimed “education reform movement.” Some of them are the Laura and John Arnold, Anschutz, Annie E. Casey, Michael and Susan Dell, William and Flora Hewlett, and Joyce foundations.

Each year big philanthropy channels about $1 billion to “ed reform.” This might look like a drop in the bucket compared to the $525 billion or so that taxpayers spend on K–12 education annually. But discretionary spending—spending beyond what covers ordinary running costs—is where policy is shaped and changed. The mega-foundations use their grants as leverage: they give money to grantees who agree to adopt the foundations’ pet policies. Resource-starved states and school districts feel compelled to say yes to millions of dollars even when many strings are attached or they consider the policies unwise. They are often in desperate straits.

Most critiques of big philanthropy’s current role in public education focus on the poor quality of the reforms and their negative effects on schooling—on who controls schools, how classroom time is spent, how learning is measured, and how teachers and principals are evaluated. The harsh criticism is justified. But to examine the effect of big philanthropy’s ed-reform work on democracy and civil society requires a different focus. Have the voices of “stakeholders”—students, their parents and families, educators, and citizens who support public education—been strengthened or weakened? Has their involvement in public decision-making increased or decreased? Has their grassroots activity been encouraged or stifled? Are politicians more or less responsive to them? Is the press more or less free to inform them? According to these measures, big philanthropy’s involvement has undoubtedly undermined democracy and civil society.

The best way to show this is to describe how mega-foundations actually operate on the ground and how the public has responded. What follows are reports on a surreptitious campaign to generate support for a foundation’s teaching reforms, a project to create bogus grassroots activity to increase the number of privately managed charter schools, the effort to exert influence by making grant money contingent on a specific person remaining in a specific public office, and the practice of paying the salaries of public officials hired to implement ed reforms.

You Can’t Fool All of the People All of the Time

The combination of aggressive style, controversial programs, and abundant money has led some mega-foundations into the world of “astroturfing.” This is political activity designed to appear unsolicited and rooted in a local community without actually being so. Well-financed astroturfing suffocates authentic grassroots activity by defining an issue and occupying the space for organizing. In addition, when astroturfers confront grassroots opposition, the astroturfers have an overwhelming advantage because of their resources. Sometimes, however, a backlash flares up when community members realize that paid outsiders are behind a supposedly local campaign.

In 2009 the Gates Foundation funded the creation of a nonprofit organization to stir up grassroots support for the foundation’s teacher effectiveness reforms. The reforms used students’ scores on standardized tests to evaluate teachers and award bonuses, abolished tenure, and ended seniority as a criterion for salary increases, layoffs, and transfers. Gates paid a philanthropy service group called Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors (RPA) $3.5 million to set up the new nonprofit. Its staff would target four “sites”—Pittsburgh, Memphis, Hillsborough County (Tampa, Florida), and a consortium of Los Angeles charter schools—where Gates was about to invest $335 million to try out its reforms. RPA’s confidential proposal, which was leaked to the media in 2011, described a potential pitfall for “Teaching First” (the nonprofit’s provisional name):

Another risk is that Teaching First will be characterized as a tool of the [Gates] Foundation and/or motivated by a political agenda other than improving public education….One way Teaching First can minimize the likelihood of being tagged as an outsider is to maintain a low public profile and to ensure publicity and credit accrue to local partners whenever possible.

Renamed Communities for Teaching Excellence, the nonprofit was launched in 2010. It survived for barely two years. Operating out of Los Angeles while trying to produce local enthusiasm for controversial policies in Pittsburgh, Memphis, and Tampa didn’t work. In addition, there was growing competition: various philanthropies, including Gates, began funding other nonprofits that sent paid staff around the country to start a variety of ed-reform campaigns. These efforts were also astroturfing, but many had greater success—in part because they had multiple and less identifiable funders. Amy Wilkins, chair of the board of directors of Communities for Teaching Excellence, summed up the problem for the Los Angeles Times (October 19, 2012): “Gates was such a big part of the funding. That made some of the partners and other funders nervous. How do you look like an independent actor? You have to show broad public support so you’re not seen as a phony-baloney front for Gates. People criticized the organization for that, and they didn’t move closer to shaking that label.”

The leaked proposal for Teaching First/Communities for Teaching Excellence reads like a how-to manual for big-budget astroturfing. Here are some of the tips:

[I]t may be important for local Teaching First staff to support and participate in campaigns that only are tangentially related to the teacher effectiveness agenda in order to build trust among allies….

Community-based organizations are much more likely to pick up the reform agenda and stick with it if they can support staff through this work and if they are able to forego other sources of funding….

With professional assistance from one or more communications firms, Teaching First will commission public opinion research and focus groups to hone a set of core messages that can be customized to each district’s context.…Teaching First should have a budget for billboards, bus and newspaper ads, and other mass media communications.

The Parent Trigger Trap

In January 2010 California enacted the nation’s first “parent trigger” law. The law gives parents control over the fate of their children’s public school if it persistently underperforms—or if they can be persuaded that it underperforms. When the parents (or guardians) of at least half of a school’s students sign a trigger petition, the signers can then choose to have the school principal replaced, the entire staff replaced, the school replaced with a privately operated charter, or the school shut down. The law was immediately controversial. The process was bound to divide communities, and it was open to abuse and outside manipulation. But most important, the law destroyed the democratic nature of public education. This year’s parents don’t have the right to close down a public school or give it away to a private company any more than this year’s users of a public park can decide to pave it over or name a private company to run it with tax dollars (see Diane Ravitch, Reign of Error, 2013). Voters—directly or through their elected officials—decide on and pay for public institutions in a democracy.

Big philanthropy’s role in the trigger law began with Green Dot, a charter school company with funding from Gates, Broad, Walton, Annenberg, Wasserman, and other foundations (for a detailed account of events, see Gary Cohn’s excellent exposé, “Public Schools, Private Agendas: Parent Revolution,” at www.fryingpannews.org, April 2, 2013). Green Dot created an organization called Parent Revolution to lobby for and then use the law. The Broad Foundation was one of Parent Revolution’s first financial backers in 2009. Once the law passed, other foundations jumped in. Parent Revolution now operates nationally and has received more than $14.8 million, most of it from mega-foundations. Walton has given $6.3 million (43 percent of the total). Other major funders are Gates ($1.6 million), Arnold ($1.5 million), Wasserman ($1.5 million), Broad ($1.45 million), and Emerson ($1.2 million).

Once the law passed, Parent Revolution didn’t wait for actual parents to initiate the trigger process; it hired canvassers to find a serviceable school. The choice was McKinley Elementary in Compton, a city of about 97,000 (97 percent African American and Latino) in Los Angeles County. Parent Revolution drafted the petition, which specified that a charter company called Celerity Education Group would take over McKinley. Paid canvassers, along with fifteen recruited parents, collected signatures and submitted the petition to district headquarters in December 2010. Then the conflict erupted. Some signers maintained they hadn’t realized they were choosing the charter school option. Fifty or sixty parents rescinded their signatures. Other parents and the district claimed the petition was invalid because Parent Revolution had imposed not only the charter option, but a specific company. Each side accused the other of harassment, including threatening undocumented residents with deportation. After a court ruled that the petition was invalid, the parent trigger drive at McKinley ended, leaving community members divided and bitter.

Parent Revolution’s second effort—at Desert Trails Elementary School in Adelanto, eighty-five miles northeast of Los Angeles—was equally disruptive. The town of more than 32,000 is about 78 percent Latino and African American. One in three residents lives below the poverty line; the largest employer is the Adelanto school district. In 2011 Parent Revolution hired a full-time organizer, rented a house for a campaign headquarters, and, according to Gary Cohn, “sent in experts to train and advise parents on everything from strategy on dealing with the school board to writing letters to help in researching potential charter schools….It even provided [campaign logo] T-shirts.”

After a contentious process, 100 of the 466 parents who had signed the petition for a charter takeover changed their minds and rescinded their signatures. The school board invalidated another 200 signatures. With just 37 percent of parents remaining, the board voted unanimously in March 2012 to reject the petition. Parent Revolution then paid to challenge the board in court. In July a superior court judge ruled that the trigger law did not provide for parents to rescind their signatures.

When petition signers gathered in mid-October 2012 to vote on which charter company would take over the school, only fifty-three of them showed up. Two parents who opposed Parent Revolution told Cohn why they felt aggrieved. Lori Yuan, mother of two students, said, “We’ve known all along this wasn’t a grassroots movement.” Shelly Whitfield, mother of five students, said, “They’re taking away all the teachers my kids have been around for years. They took over our school, and I don’t think it’s fair.”

In April 2013 Parent Revolution blundered in Florida when it tried to pass off a pro-trigger video it had produced as the product of a local organization called Sunshine Parents. News of the chicanery broke shortly before the Republican-controlled state senate was to vote on a trigger law. Supporters had been confident of victory, but the video revelation helped to change some minds. The bill failed, 20-20 (Miami Herald, April 30, 2013).

The Very Model of a Modern Major Trigger Law

According to a report by the National Conference of State Legislatures, parent trigger legislation had been brought up in at least twenty-five states as of March 2013. In addition to California, six states have enacted versions of it: Connecticut, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio (a pilot program in Columbus), and Texas. Much credit for this rapid expansion goes to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the now notorious organization of businesses, private foundations, and over two thousand conservative state legislators. ALEC meets twice a year in closed sessions to draft model legislation on various issues; state representatives can then introduce the bills in their legislatures. According to ALEC’s website, “Each year, close to 1,000 bills, based at least in part on ALEC Model Legislation, are introduced in the states. Of these, an average of 20 percent become law.” Many of the controversial “stand your ground” self-defense laws, voter ID laws that suppress minority voting, and parent trigger laws are based on ALEC models.

Despite its obviously political agenda, ALEC is a tax-exempt nonprofit. The Gates Foundation gave the group a $376,635 grant in 2011 “to educate and engage its members on efficient state budget approaches to drive greater student outcomes, as well as educate them on beneficial ways to recruit, retain, evaluate and compensate effective teaching based upon merit and achievement.” After several exposés of ALEC’s work prompted some corporate members to resign, the Gates Foundation announced in 2012 that it would finish out its grant to ALEC but not undertake future funding (Roll Call, April 9, 2012).

He Who Pays the Piper Calls the Tune

Philanthropies risk losing their tax-exempt status if they donate directly to candidates for public office, so some foundations have tried other ways to ensure they have the people they want in key posts.

The Los Angeles–based Broad Foundation stipulated in the contract for a $430,000 grant to New Jersey’s Board of Education that Governor Chris Christie remain in office. As the Star-Ledger reported (December 13, 2012), the Newark-based Education Law Center had forced the release of the contract through the state’s Open Public Records Act. For the center’s executive director, David Sciarra, “It is a foundation driving public educational policy that should be set by the Legislature.” The Broad Foundation’s senior communications director responded, “[W]e consider the presence of strong leaders to be important when we hand over our dollars.”

The foundation sector will fight reform ferociously—as it has in the past. When asked to forgo some influence or contribute more in taxes, the altruistic impulse stalls.

The keep-Chris-Christie clause was not the first time a staffing prerequisite was discovered in a grant contract with a public entity. In 2010 Washington, D.C. schools chancellor Michelle Rhee negotiated promises for $64.5 million in grants from the Broad, Walton, Robertson, and Arnold foundations. Rhee planned to use part of the money to finance a proposed five-year, 21.6 percent increase in teachers’ base salary. In exchange she demanded that the union give her more control over evaluating and firing teachers and allow bonus pay for teachers who raised student test scores. In March 2010 the foundations sent separate letters to Rhee stating that they reserved the right to withdraw their money if she left. They also required that the teachers ratify the proposed contract (Washington Post, April 28, 2010). Critics challenged not only the heavy-handed intrusion into an acrimonious contract negotiation but also the legality of the stipulation on Rhee: hadn’t she negotiated a grant deal that served her own employment interests? The teachers ratified the contract, but the extremely unpopular Rhee resigned in October 2010 after Mayor Adrian Fenty, who had hired her, lost the Democratic mayoral primary. By that time, much of the grant money had been spent, and the new schools chancellor kept Rhee’s policies.

Private foundations have used another tactic to exert influence on the Los Angeles Unified School District: they paid the salaries of more than a dozen senior staffers. According to the Los Angeles Times (December 16, 2009), the privately financed “public” employees worked on such ed-reform projects as new systems to evaluate teachers and collect immense amounts of data on students. Much of the money came from the Wasserman Foundation ($4.4 million) and the Walton Family Foundation ($1.2 million); Ford and Hewlett made smaller grants. The Broad Foundation covered the $160,000 salary of Matt Hill to run the district’s Public School Choice program, which turned so-called low-performing and new schools over to private operators. Hill had worked in Black & Decker’s business development group before he went through one of the Broad Foundation’s uncertified programs to train new education administrators. A Times editorial on January 12, 2010 asked, sensibly, “At what point do financial gifts begin reshaping public decision-making to fit a private agenda?…Even the best-intentioned gifts have a way of shifting behavior. Educators and the public, not individual philanthropists, should set the agenda for schools.”

A Modest Proposal

Big philanthropy is overdue for reform. The goal should be to reduce its leverage in civil society and public policymaking while increasing government revenue. Some possible changes seem obvious: don’t allow administrative expenses to count toward the 5 percent minimum payout, increase the excise tax on net investment income, eliminate the tax exemption for foundations with assets over a certain size, and replace the charity tax deduction with a tax credit available to everyone (for example, all donors could subtract 15 percent of the total value of their charitable contributions from their tax bills). In addition, strict IRS oversight of big philanthropy—especially all the “educating” that looks so much like lobbying and campaigning—is crucial.

Another reform would require private foundations to “spend down” their endowments over a designated number of years. They would no longer exist in perpetuity. This idea has some promise of success: the living donors of several mega-foundations, including Bill and Melinda Gates, have already decided to spend down and are recruiting others to do the same.

The foundation sector will fight reform ferociously—as it has in the past. When asked to forgo some influence or contribute more in taxes, the altruistic impulse stalls. The foundation sector acts like any other powerful interest group. The Obama administration, for example, tried several times to lower the charitable deduction cap, but the foundation lobby battled each effort successfully. Still, the reforms are sound, necessary, and worth pursuing.

Meanwhile, the public needs more critical, in-depth information. The mainstream media are, for the most part, failing miserably in their watchdog duties. They give big philanthropy excessive deference and little scrutiny. Public television and radio live on big philanthropy’s largess. Collaborative programming with mega-foundations has undermined the credibility of major for-profit news organizations as well as public media, especially on health and education issues.

Early twentieth-century skeptics were rightly suspicious of plutocrats deciding how to improve the human condition and then paying to translate their notions into public policy. Now it’s time for a new progressive era—complete with muckrakers and trust-busters to cast a critical eye on big philanthropy.

Joanne Barkan is a writer based in New York City and Truro, Massachusetts. Her other articles on the education reform movement and big philanthropy can be found here.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly of the Social Sciences, Summer 2013.

A slightly modified version of this article appeared in the Fall 2013 print issue of Dissent under the title “Big Philanthropy vs. Democracy: The Plutocrats Go to School.”